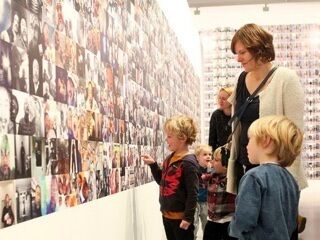

FOMU collection

Project Tegenlicht: New techniques for preservation of photo archives

When the condition and the volume of photographic film is so challenging, how do you make such important archives accessible? Many archives and museums are currently wrestling with this question.

This led to FOMU, ADVN (the archive for national movements) and KOERS (museum of cycle racing) joining forces to launch Tegenlicht (meaning backlight in Dutch). Tegenlicht is a Flemish government project aimed at catching up with the backlog in digital collection registration.

FOMU, ADVN and KOERS are making accessible six photographic film archives. The selected archives illustrate political, social and cultural aspects of Flemish life from the 1950s to 2000.

FOMU chose Herman Selleslags’ film negatives for this project.

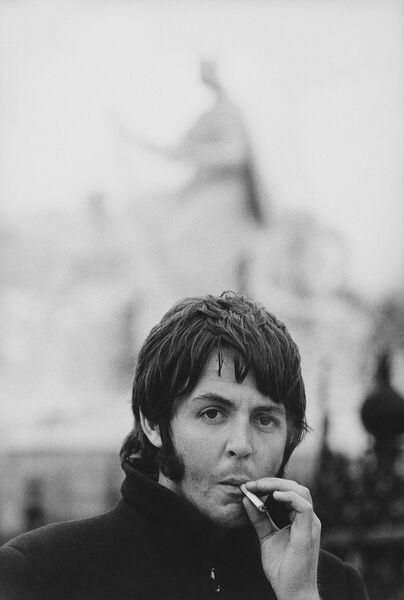

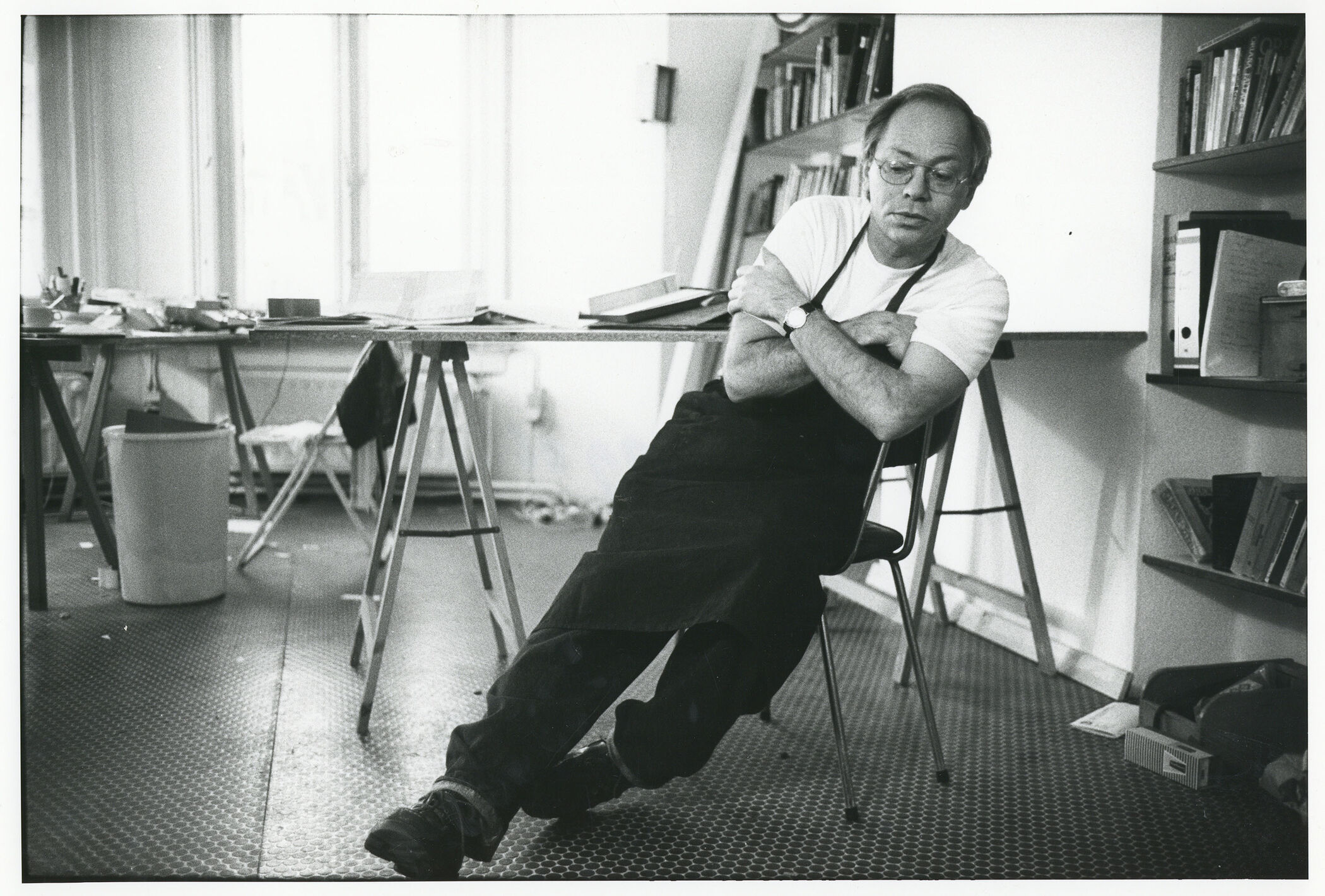

Herman Selleslags, self portrait, 1986, Collectie Fotomuseum Antwerpen © Herman Selleslags

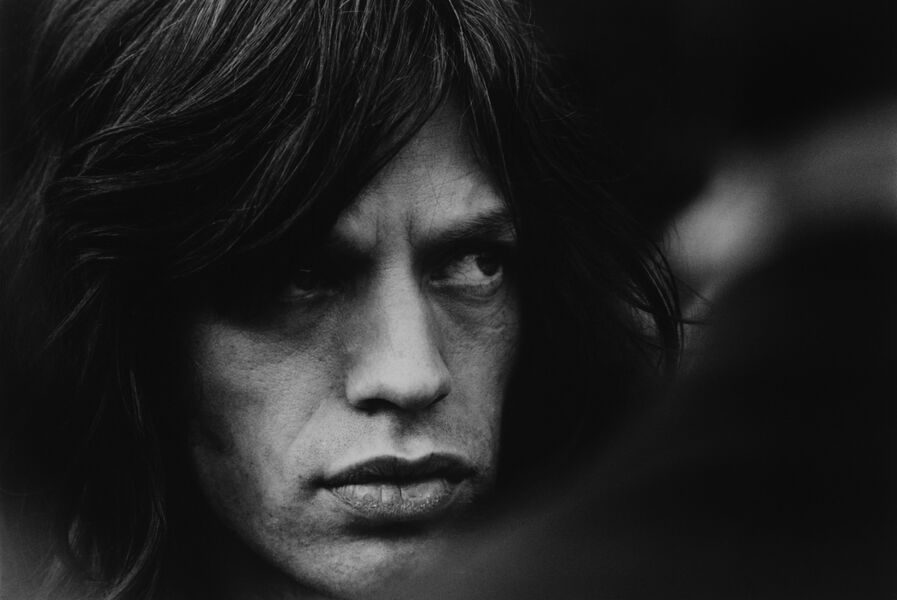

Herman Selleslags

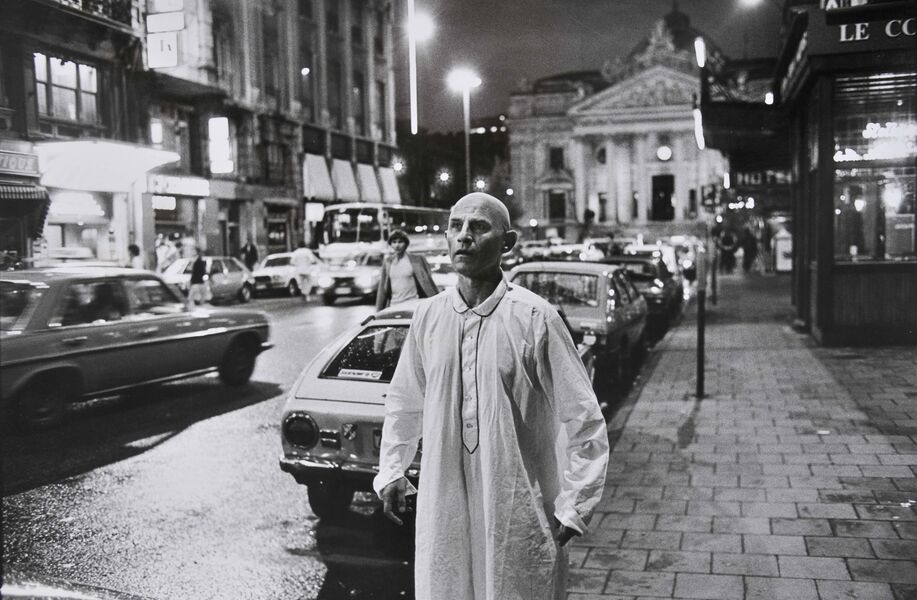

Herman Selleslags is one of the most famous photographers in Belgium and has been magazine Humo’s house photographer for fifty years. Herman and Rik’s archive contains over half a century of national and international history covering topics from politics and media to pop music and daily life.

In 2015, FOMU obtained the archive of Herman Selleslags (1938) and that of his father Rik Selleslags (1911-1982) for its collection.

There are many challenges in the preservation of such an archive. The photographs are fragile: photographic film can deteriorate, and photographs can suffer from discoloration. The museum has worked on preserving the Selleslags archive since it was donated, but what does that actually entail? What goes on behind the scenes, in rooms filled with archive boxes and bubble wrap?

BEHIND THE SCENES

Studio Herman Selleslags, 24 august 2016 © Guy Voet

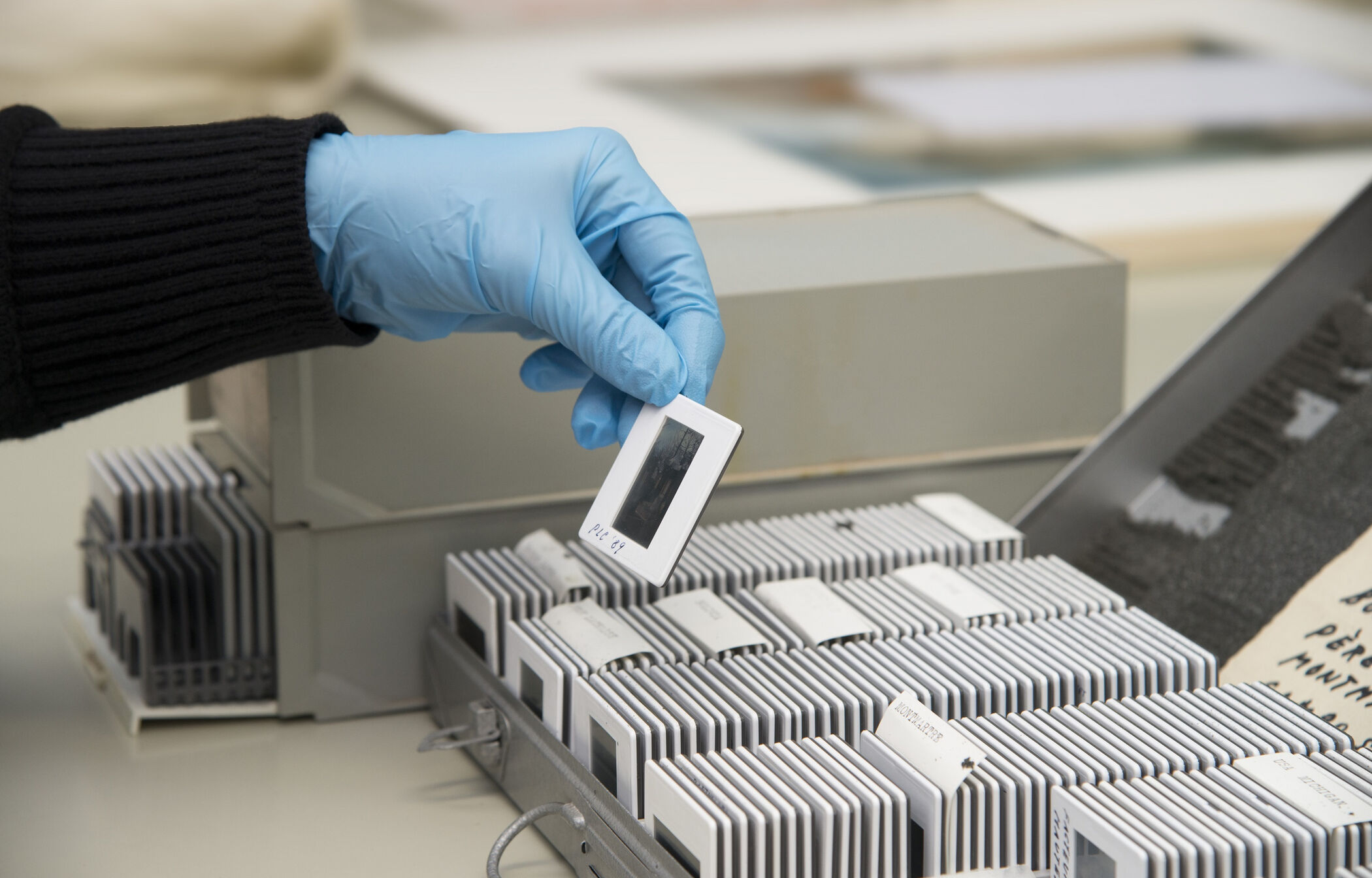

In order to preserve the Herman and Rick Selleslags’ archive for future generations, the objects are described, digitised, cleaned and packed in acid-free paper. Acid-free paper is used to prevent materials from discolouring and to protect from other environmental threats such as dust and light.

Digitisation is the making of a digital image from an analogue original. Digitisation allows for the collection to be consulted without the need to remove the original images from their packaging.

The fragility of the material and the sheer volume of it mean that this is an expensive and labour-intensive project. This process and the archiving are further complicated by the fact that Herman changed his system of organisation several times during his career: some sections are arranged chronologically and others alphabetically by subject.

"I did have a system myself, but I’ve been working for sixty years now, and during that time I changed it three times", says Selleslags. "Not smart, of course. And then there are the exhibitions and books: I remove things and don’t put them back in the right place, it would be too much work."

A few years ago, FOMU started the digitisation of approximately 2,400 of Rik Selleslags’ sheet film. Around 1,500 of Rik’s glass plate negatives will follow in 2022, supported by the GIVE glass plates project. In addition, a member of the collection staff will spend a year packing 25,000 photographs Herman Selleslags took for Humo in acid-free paper. The photographs all have a unique object number, which is noted on the back.

Herman and Rik’s photographs are in great demand for exhibitions and publications. This means that other sections of the archive also need to be processed quickly.

TEGENLICHT

Tegenlicht is a Flemish government project aimed at catching up with the backlog in digital collection registration.

Tegenlicht is a response to the accumulation of undigitized and undescribed photographic film archives. The backlog arose from the difficulty of preserving film negatives due to:

- the fragility and instability of film in comparison with photo prints;

- the need to store film cool, which is not the case with photo prints;

- the larger size of photographic film archives relative to photo print archives;

- film strips are usually stored in in plastic sleeves, photo prints generally consist of a single image;

- film is more difficult to describe than positive images since it is more difficult to identify the representation.

With these difficulties in mind, the question is how to proceed when you have over 300,000 individual images. For example, does each film strip have to be removed individually from the sleeve in order to digitise it?

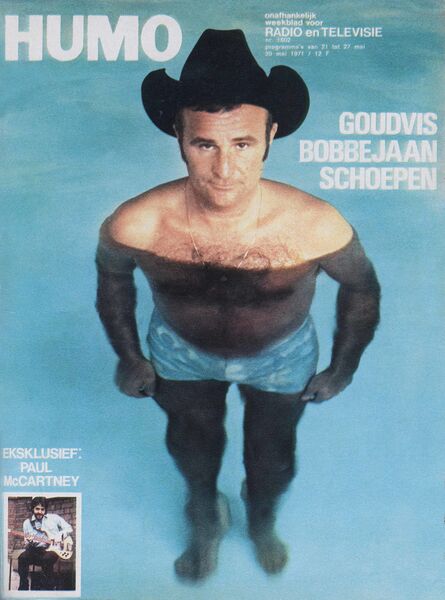

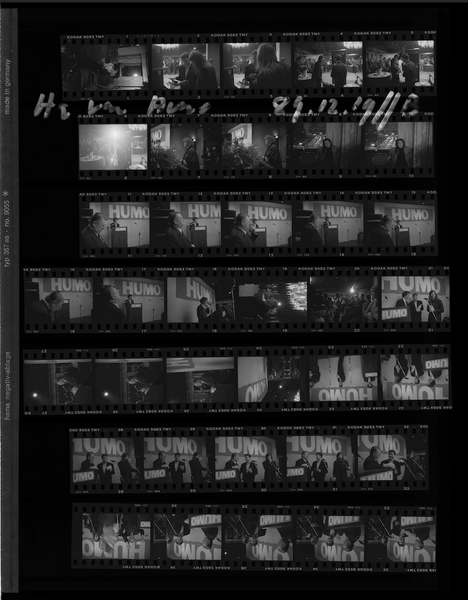

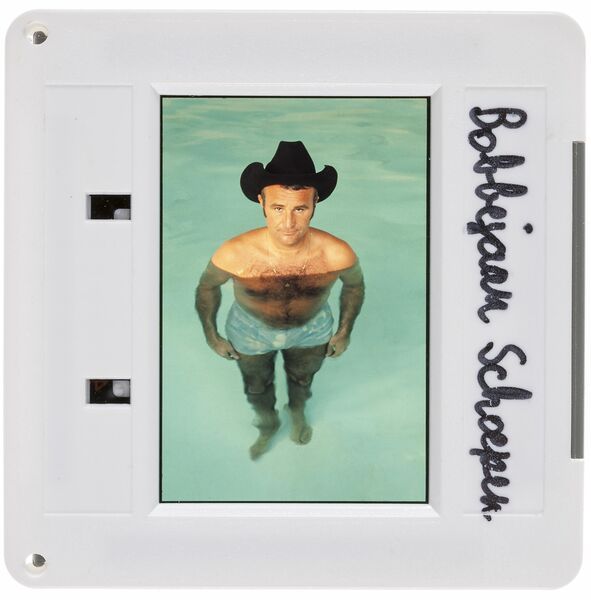

The contact sheet method

During Tegenlicht, FOMU collection staff applied new techniques to make it faster to digitise and describe photographic film. The first was the digitisation of film in plastic sleeves. Normally the film would be removed from the sleeves and digitised per strip, but now the contact sheet method was used. This resulted in fewer photographs needing to be taken: just one per contact sheet instead of 36. Using Tegenlicht, FOMU digitised 300,000 of Herman’s images on approximately 10,000 negative sheets. The method is 35 times faster, and that means time savings of months or even years. Herman Selleslags’ archive is thus becoming accessible much earlier.

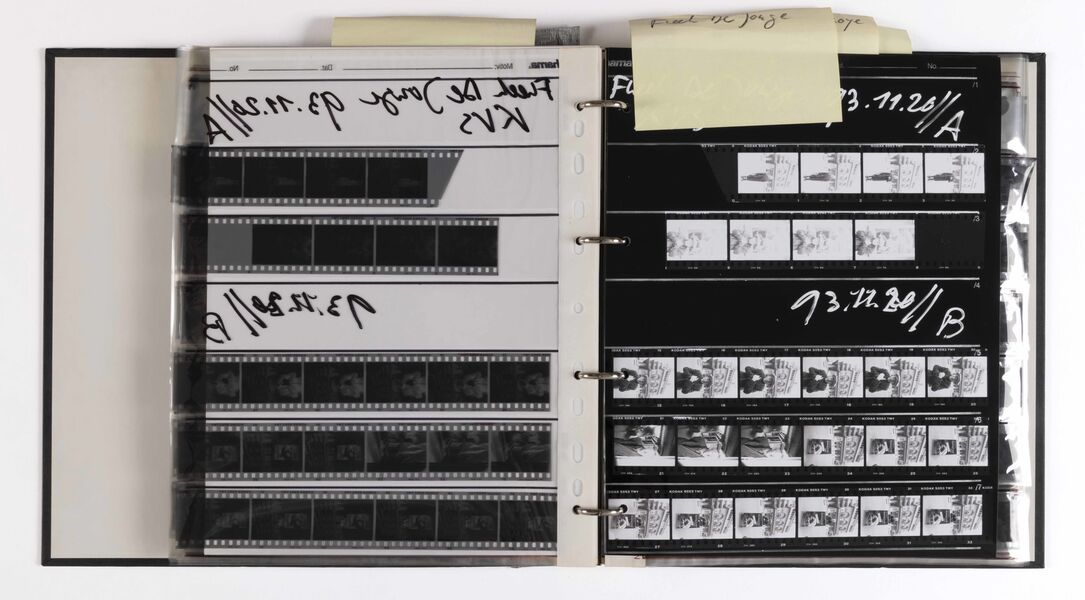

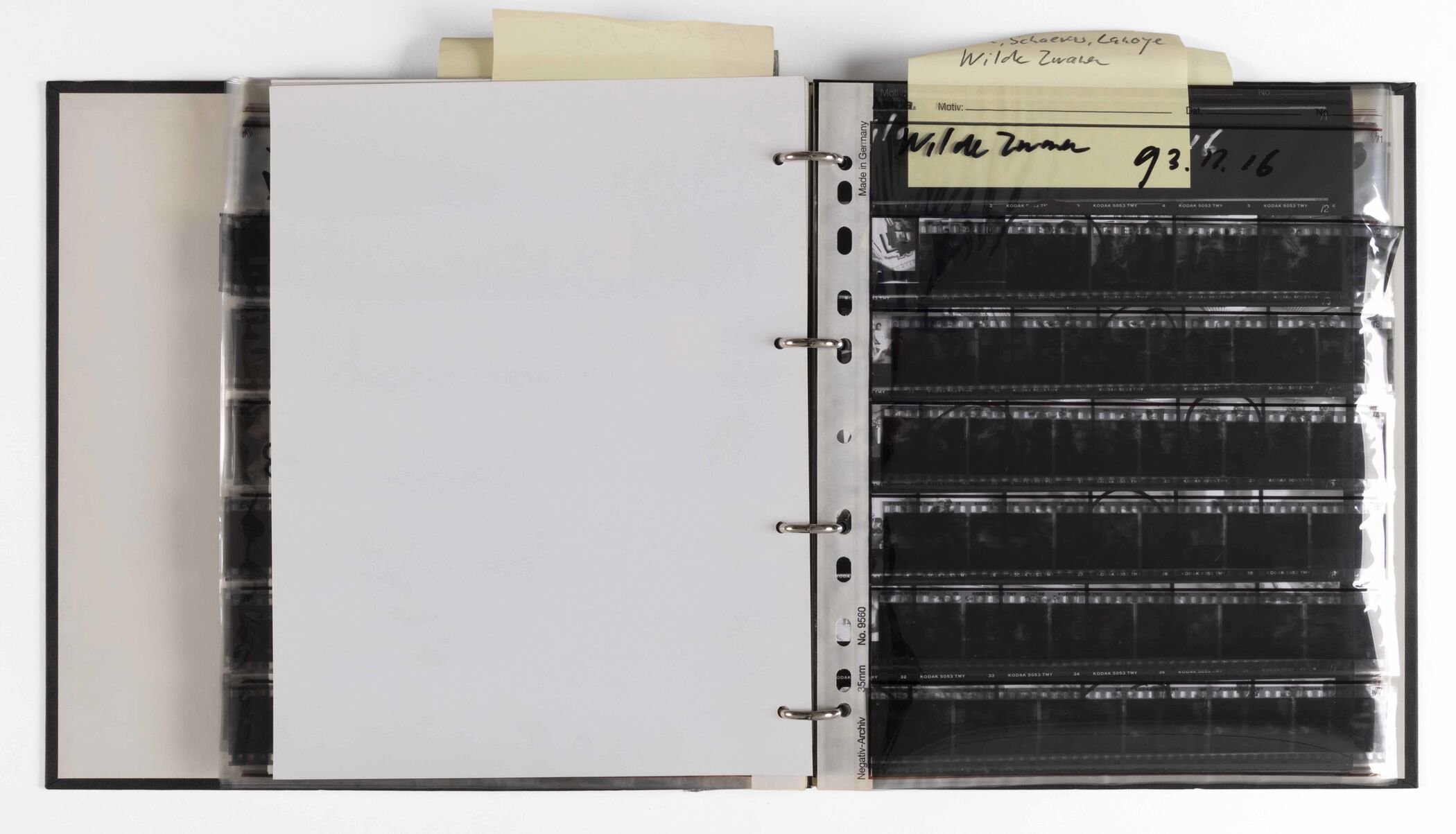

Folder with negative sheets and contact sheets Herman Selleslags, 1993, Collection Fotomuseum Antwerp

The method is also interesting because the order of the film strips is retained and this provides insight into the photographer’s working method and selection process. Photographers often make contact prints of negative sheets so that they have an overview of the images they’ve shot. These prints can show the moments before and after an iconic photograph was taken. By digitising the negative sheets, FOMU gains an overview of the images from Herman Selleslags’ film archive and how they relate to each other

Glassine paper sheets and contact sheets Herman Selleslags, Collection Fotomuseum Antwerp

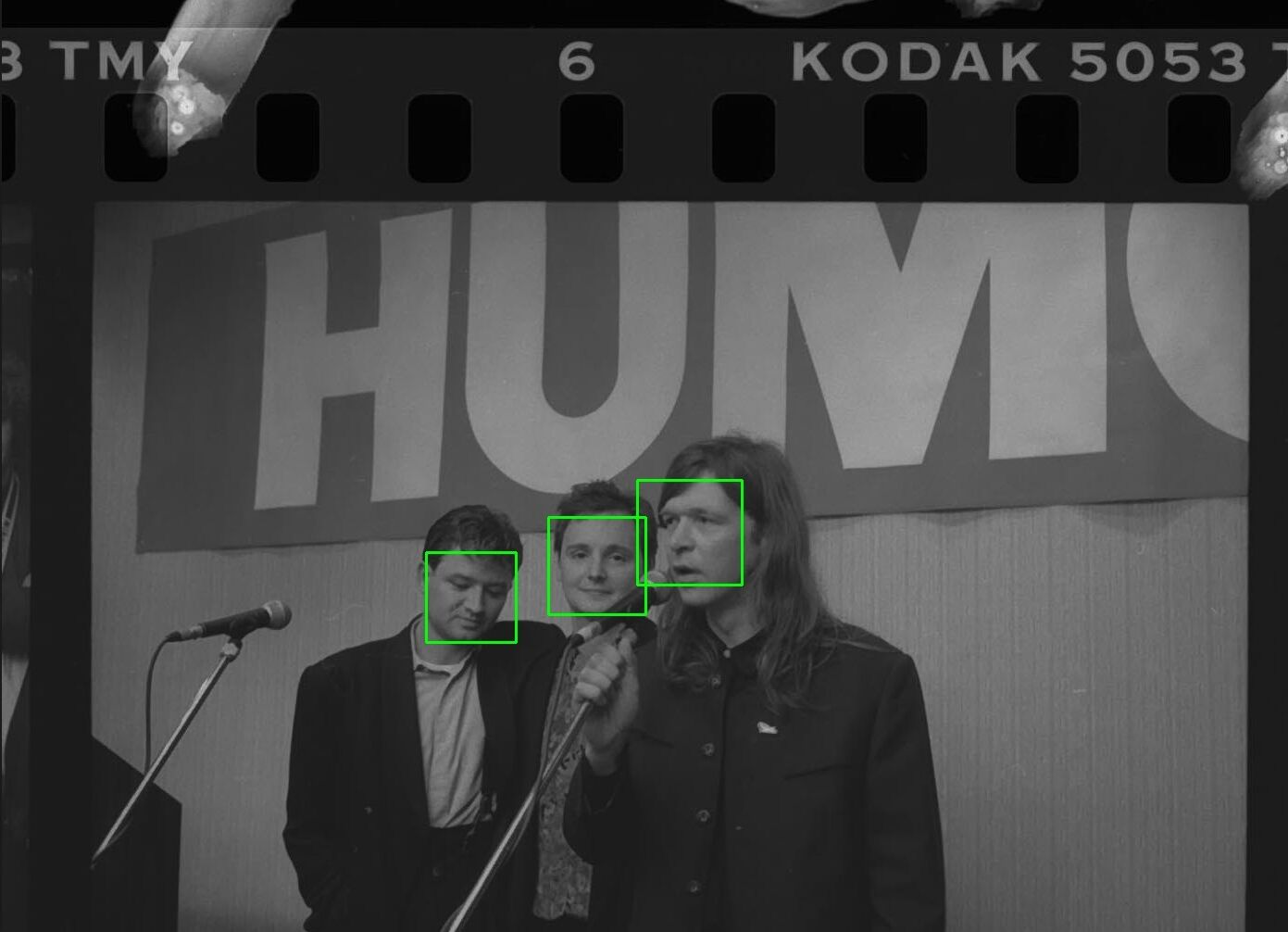

Artificial intelligence and facial recognition

During the Tegenlicht project, collection staff also explored the fastest way to describe the film negatives. They used artificial intelligence that recognises and clusters the persons who appear in a photo. For example, Bart Peeters is depicted on a digitised negative sheet and also in other photographs from FOMU’s collection. His face is recognised as Bart Peeters by the computer and every appearance of Bart Peeters is linked. This assembly of faces is first checked by the collection staff: has the computer really identified Bart Peeters correctly every time, or has someone else’s face sneaked in? After verification, the information is linked to FOMU’s online catalogue so that all images containing Bart Peeters can be found quickly.

Packing

Following digitisation, FOMU packs the film strips in acid-free paper. Photographic film is made from cellulose nitrate, cellulose acetate or polyester. Gases and vapours release as a result of temperature changes, ageing and humidity. These gases can escape more easily through paper than plastic. The are each assigned a unique item number and then returned to the climate controlled FOMU depot.

What next?

Tegenlicht has been responsible for innovations that make the digitisation of Herman and Rik Selleslags’ negatives so much faster. This and the other projects will make the Herman and Rik Selleslags’ photo archive fully accessible in a few years and preserved for future generations. The hundreds of brown archive boxes are increasingly making way for blue museum boxes and a digital catalogue.