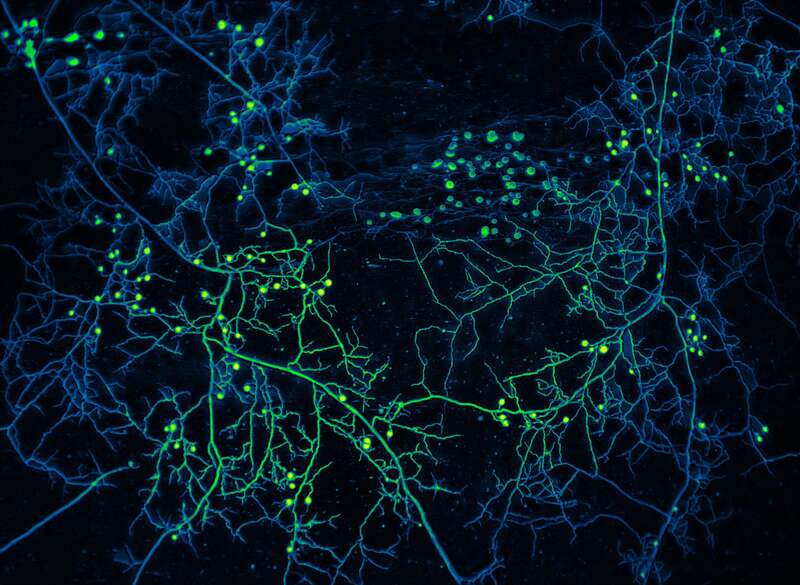

A high-resolution mycelium network @ Loreto-Oyarte-Galvez

Nineteen Discussions for Photographers and Artists in the Age of Climate Crisis

Editor's note. 'Nineteen Discussions' forms the basis for a workshop for and by photographers, students, researchers, curators, culture professionals and visual artists, which will take place on Friday October 14 at FOMU, the museum of photography in Antwerp. More information here.

This workshop is part of Rights of Nature, a two-day cross-disciplinary program by SLARG, in close collaboration with Klimaatfestival Antwerpen, FOMU, Curatorial Studies KASK Gent, and Kunsthal Extra City. Rights of Nature explores the role of law, philosophy and arts in relation to "the rights of nature". It brings together various forms of research and translates this to a wide audience.

Taco Hidde Bakker

02 okt. 2022 • 6 min

1. Should we set the terms of the debate first? Climate change? What change? Has the climate not always been changing? No, others will say, the term ‘change’ is a political frame attempting to downplay the situation. Should we instead be talking about ‘the climate crisis’, ‘climate breakdown’, ‘global heating’? Or even ‘the Anthropocene’, the age in which humanity is becoming a geological force on par with the great forces of non-human nature?

2. Is your image-making a handmaiden of global warming, or could it be a tool for cooling, too? To what extent is your work tied up with the fossil fuel complex? Do you think it necessary to decarbonize your practice? Is it important to develop ways of engaging with the camera that do not (implicitly) reproduce the ideology of the economic and cultural systems that seem to lie at the root of contemporary climatic turbulence?

3. More important than individual change is collective change. In rather individualized societies like ours, at least on the level of ideology, the term ‘collective’ is like anathema – even though ‘we’ coordinate so much together. How should institutions of culture and learning contribute to addressing the crisis, not only with words but with meaningful actions?

4. Photography is both science and art – a computed and projected image requiring energy-intensive technologies for its production and distribution, yet also a cultural means of storing and transmitting eyewitness accounts, views on the world, and (visual) knowledge. While a photograph can show the surface appearance of something happening in a particular place at a specific moment, it can also implicitly carry warning signs and become a call for change.

5. Photography is both science and nature, equally invented and discovered. Some would say there’s no essential difference between humans and nature, or between technology and nature. (The clothing you’re wearing now is a form of naturalized technology – we don’t notice it as technology anymore.) If you do believe there’s no difference, why bother even making and sharing images (an act only confirming the difference)? As the philosopher Vilém Flusser would say, an image (representation) comes to replace the presence that it re/presents. Is an image (made or taken) part of the (natural) environment? Can images contribute to re-establishing healthier relationships with non-human nature?

6. The climate crisis looms so large and so intricately touches upon every aspect of life that it seems to defy our imagination. This led Timothy Morton to speak about ‘hyperobjects’ – such abstracted phenomena as the financial system, the internet, or anything else so complex that our intellect and imagination can barely touch or visualize ‘it’. To wake up to this notion can exert paralyzing effects. The little we can do perhaps only makes sense to redeem our tiny souls. Or is there sufficient reason to keep believing in the famous ‘butterfly effect’ – small changes rippling into fundamental shifts down the line? But will there be enough time left?

7. If the climate crisis is indeed a hyperobject, how could it ever be adequately depicted and imagined? Is it necessary to re/present it as image? Aren’t images always too small, excluding far more than they include? The map never covers the territory. Should the photographer or artist even (attempt to) take up the task of visualizing the intricacies of the crisis?

8. Poetry or propaganda; or poetry and

propaganda?

9. Who do we want to reach with our images, and when? Should we preach to the choir? Should we attempt to reach influential people so as to influence them in turn? Do we want to reach fellow contemporary beings, or could our work become a message that’s received by who knows which future generation? An existential issue like the climate crisis seems to ask for massive communication on a global scale. So why not resort to popular media such as the blockbuster movie, manga, the graphic novel, or the children’s story to transmit these urgent messages quicker and more effectively?

10. The unfolding apocalypse seems to radically disturb our imagination and messes up received senses of time and space. Our grammar is being shaken to the core. What do past, present, and future tenses mean now? And if images do possess any grammar at all, what does that grammar convey?

11. If the climate crisis were treated with the same urgency as the Covid pandemic, which resources of the imagination would we have to mobilize in order to do battle with it? Will the costs of doing nothing or little prove more expensive than investing immediately? Most politicians and their constituents are penny wise, pound foolish.

12. There’s value in direct action, activism, and ‘artivism’, as they can inspire changes in behaviour, but shouldn’t we also ask to what extent action contributes to further heating? Is ‘passivism’ an alternative? Once the fires are burning, it’s hard to extinguish them. We’re too captivated by the flames.

13. Humans seem to be an optimistic species by nature, with high hopes for their survival by means of their perceived superior imagination and capacity for improvisation and technological solutions. But can we really geo-engineer our way out of this predicament? Should we take the warnings against hubris, techno-optimism, and ‘solutionism’ more seriously?

14. Let the crisis send shivers down our spines! Witnessing the powers of floods, storms, fires, and droughts (even if only as a secondary witness by means of recording media like photography or film) may cause your entire nervous system to feel the gravity of what’s going on. Can real change for the better occur without enough people feeling grief, pre-traumatic stress disorder (anticipatory anxiety about the unfolding disaster) or ‘solastalgia’ (nostalgia for healthier ecologies and landscapes before their drastic depletion)?

15. Does the climate crisis call for the revision (or abolishment) of singular authorship and copyright? Does it call for creative and ecological commons, shared not only among humans but with non-human life forms too?

16. Should photography and the visual arts strive to re/present non-human nature? In which ways could such a thing contribute to political representation of non-human life-forms? In which ways could photography and visual art speak for rivers, mountains, ice, storms, fires, plants, fungi, organelles, mycelial networks, and so on? How can imagery contribute to ecological justice and accountability?

17. How can we change our practice and behaviour from the bottom up as well as from the top down, as much on the individual as on the collective level? Are our democracies not too entangled with the dirty business of the fossil fools? Is there a way to save both a just and inclusive democracy and a habitable planet for all life-forms (so interdependent on one another)?

18. In which ways can photography and visual art contribute to multigenerational thinking? How can it link pasts, presents, and futures? How can it address the yet unborn? The question has been asked before and deserves to be asked again and again: Are we being good ancestors?

19. Perhaps humans are too smart to save the biosphere? Possibly, we’ll choke in our own filth – like the cyanobacteria of millions and millions of years ago, whose oxygenic waste ultimately provided the conditions for other, more complex life-forms.

This is a revised version of the manifesto that was first published as a broadsheet in the centerfold of the 2020 catalog of the Oslo Fotobokfestival: The Climate Emergency in 50 Rounds, curated by Ethan Rafal.