‘There is a war in our country. What are we talking about?’ Towards the end of our second conversation, Sophia Bulgakova reminds me firmly of the main reason behind the very existence of the book In Pieces: its context – war, occupation, full-scale invasion. The project is a powerful joint endeavour presenting the works of five artists affected by the war in Ukraine and its consequences. For some of them, the war is the ultimate reason why these works exist in the first place – to cope with that very complex mix of pain, anguish, worry, and trauma that war can create. For others, their works exist despite the war, as a form of resistance to its very existence.

In November 2022, at the invitation of the Amsterdam-based initiative Growing Pains, artists Sophia Bulgakova, Lia Dostlieva, io ola lanko, Katia Motyleva, and Kateryna Snizhko came together to explore how their lived experiences could be translated into a joint artistic publication. To what extent their work would be collaborative or individual, or what the process would look like, was yet to be defined. Published in the summer of 2023, a zine titled Vulnerable Manifesto offers a glimpse of the vision and the modus operandi behind the publication In Pieces, released in November 2023.

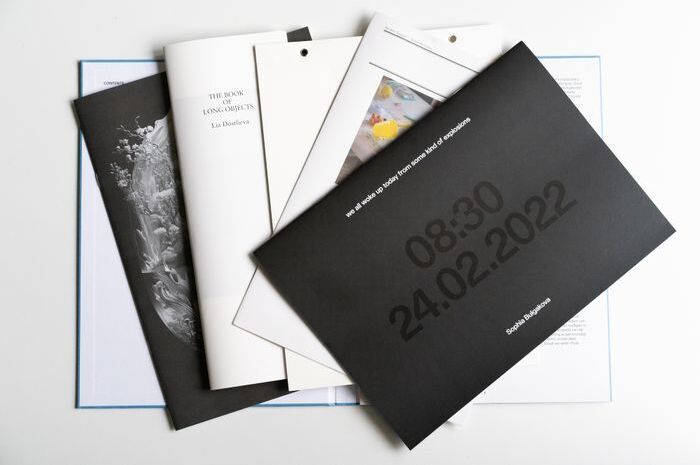

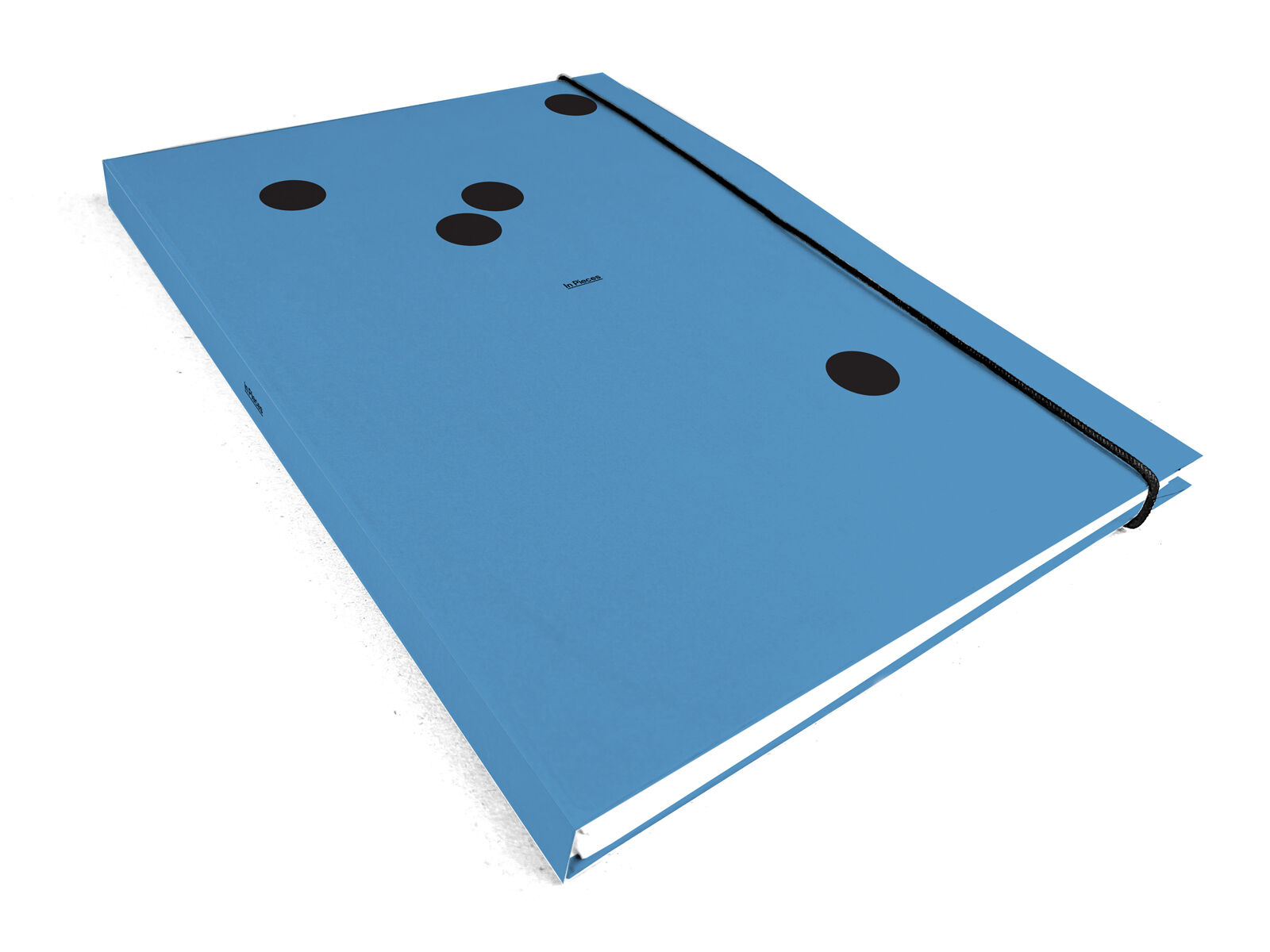

In Pieces is a collection of five works that ‘speak of the multiplicities and contradictions of living in a shattered present’ while having a child in mind. The works are held together sapiently by the designer Ayumi Higuchi. Some works directly address younger audiences, while others draw on the artist's own memories and experiences. Sophia Bulgakova’s we all woke up today from some kind of explosions, a collection of fourteen stereograms, each embedded with a message from a chat between the artist and her friends, touches on the fragmentation of narratives and experiences and their invisibility.

The Book of Long Objects, by Lia Dostlieva, pairs stories of displaced women from different generations of her family with images following her own memory thread, elaborating on intergenerational trauma and the construction of memories and commemorative practices. Istopia by io ola lanko is a game-like ecosystem of fantastic characters, personalities, narratives, and locations, a world of possibilities that allows the exploration of life’s complex emotions through play and interaction. I wish this paper had remained blank, by Kateryna Snizhko, probes the artist’s resistance to the external demand for artistic expression of traumatic experiences by employing images disassembling with a forceful imprint method. Lastly, Mother Tongue, by Katia Motyleva (with a poem by Lyuba Yakimchuk), explores the connection between food, language, and motherhood in an intertwined relationship of meanings and identities, passed through generations via the most elementary process – feeding and being fed.

I met with the artists on various occasions during public presentations and private conversations. The text that follows is a nonlinear account of such exchanges, one that is itself an attempt to answer the many questions that kept informing my experience of their work and the book that contains them. Many conversations about visual practices during wartime and our expectations towards their scope and function are yet to be had. How can visual, artistic practice be both an instrument and a reaction to a condition of intense distress? What is the tension between its intention and its fruition, its consumption even, and the necessary opacity of such an endeavour? Ultimately, what do we do with images?

Elisa Medde: Since the beginning, you were accompanied by designer Ayumi Higuchi, whose task was to create the physical space in which all the individual contributions could live together as a publication – a challenging task, as your practices differ very much from one another and are also continuously evolving. The result appears as a collection of booklets, each with its own identity, wrapped in a hardcover that doubles as a sort of protective shield. I wonder how this informed and shaped the creation process, perhaps directing it in unexpected directions.

Sophia Bulgakova: It was decided it would be a book. And then we started with not being sure if it would be one book, which we would create together, or separate publications taking different forms. It was a very collaborative process, but it was also a very deep individual search for each of us. In a way, we kind of supported each other through this process, but then I think a lot of the findings were really on a personal level, based on what we, each of us, were going through.

EM: Your practice engages deeply with sensorial space, developing itself through site-specific installations. Your works live in space, often allowing for collective and individual experiences of it simultaneously. How did you translate that into a book form?

SB: I always work between collective and individual experience. It’s also what the book is –it’s like your own vision, but also a collective memory. The plan for this project is that it’ll also become a light installation, where the text will be projected or reflected through semi-transparent surfaces. I’m also starting to experiment and research AI and censorship, which originates from personal encounters during the war. A part of the project will go into physical installation with the materials collected next to the book. So you can have a book as a published version and take it home, keep it and have it, and then you have a physical experience, which allows you to submerge yourself in information entirely: the disappearance of information; the information that was missing; the messages that don’t get across; all the newsletters that don't get across; all the photos that don’t get across; and how systems of oppression within media, within Western media and Russian media propaganda, is kind of diluting information and concealing it from you.

When the full-scale invasion started, I switched 100% to activism and started organising fundraisers, being very hyperactive. And just doing and doing and doing and doing and doing. For months, it was very difficult for me to connect this to my art practice. The two felt unrelated, and nothing made sense. My projects didn’t make sense. My previous work didn’t make sense. The only kind of reasoning was, I need to do something. I needed to do something because I felt powerless and the world didn’t make sense. And then, through this project, I kind of brought one reality into another. The entire world existed in my phone. Instagram became the place to look for aid – I would constantly talk to people about how to move them from one place to another, calling friends or people I didn’t know. Everything existed on my phone. Without my phone, the world was not there. And then it made sense that my phone leaked into my project and became a kind of gateway. I think that the project came to be through understanding this and speaking about it and processing it. So, it merges this kind of hyperactivity and hysteria of needing to do something. Nothing makes sense with my reality here in my art practice, so that was my way of dealing with it.

**********

EM: I think that one of the most powerful aspects of the book is how the experience of each booklet translates into a form of communication about the larger body of work. In Sophia’s case, when going through the stereograms, I inevitably have to think about the frustration of how to decipher interrupted messages and how to extrapolate them out of a fragmented WhatsApp conversation or voice recording. Everything comes across from a conversation that doesn’t happen in real time and doesn’t happen physically in the same space but keeps you permanently suspended because of its non-simultaneity. We are now used to real-time conversation, and these works oblige us to reflect on the space in-between, the gap between something happening and us learning about it – the inability to share experiences with loved ones, to only be able to hear about it afterwards. When going through the pages of Kateryna’s I wish this paper had remained blank, the first thing I think of is ‘time’ – its pace and the passing of it. So it was very interesting for me to read in the zine that during the making of the project, you were focusing on the difference between the ways kids and adults experience the present. While kids are naturally able to stay in the present, they cannot articulate it. They cannot speculate and ponder what it actually means to be in the present, whereas we adults have a very hard time staying in the present – we tend to be a little obsessed about being able to describe it. We oscillate between the past and the future. And so this idea of time and pace filters through when flipping through the pages of what could be a notebook. But then it’s also a series of fragments, something that has been disaggregated and then reassembled, put together, with texts going through it. How important was it for you to establish a pace of the page experience and of the relation between the images and the text?

Kateryna Snizhko: Repetition is an important aspect here: there’s repetition in the imagery and repetition with the text because each page starts with a variation of the same phrase, ‘I wish for this paper to remain blank’. So it’s all about the same sentence, but it’s also about remembering certain things, yet not precisely. Working with kids and trying to make paper with them out of the same leftovers that are used in the printing process was interesting for me because then you really feel this different perception of the present that, for sure, they cannot articulate, while then really being able to remain in the moment. So what happens with this repetition is actually the reflection of this loop of present, past and future. The present for adults is always overlapped with thoughts about the future and some experiences from the past, which repeat in a kind of loop. So, for me, it was the construction, the construction of the feeling, but also the construction of the time, the moment, and making the same thing over and over again. But thinking about it in a little bit, in a slightly different way. Turning it into a time element.

******************

EM: Ola, I was wondering, there’s a very powerful interactive aspect in your work. Generally, your practice is multi-layered; you work naturally in a trans-medial way. You always navigate different layers. In Istopia, you’re creating a universe, a full mythology, of characters and roles and feelings and sentiments and environments while at the same time stepping off of it: the work is a game, so once all the elements are there, you leave it, and it’s someone else who has the task to activate it. It becomes something that someone else makes alive. How did it feel for you to have this step-back moment? To create a whole world and then let it go? Of course, this also happens when you create artwork, but in this case, I feel it’s even more poignant.

io ola lanko: When you step out, the magic happens. People start to make connections; they start to explore. There was a moment when I was testing the game with a friend’s child, and I asked her, ‘How was your day at school?’ Then she took out some images that were a little scary, so I asked her what happened. And she could tell me what had happened that day at school. The images became a vehicle, a vehicle to talk or to get somewhere. They created a connection, in this case between a father and a daughter, to talk, discuss, and explore their internal states together. You can assemble your world freely, the way you want.

*************

EM: Katya, you refer to language as something that you can switch between – to adapt or change code. But with food, you say, you have to eat every day, and food is what you have to make every day for your daughter. And food is the simplest yet most political of all codes or languages. You can start with access to food, its abundance and scarcity, and its political deprivation. Food is also a vehicle for culture, for identity, for history, for tradition. So it becomes extremely visceral, and in your body of work, I think it’s very evident how it’s something that allows you to reflect on many of these aspects. There’s a powerful relation between the images of food and the poetry in your work on the pages of the book. In certain moments, the poem felt like a lullaby, or at least it came out naturally for me to read it with such intonation. And it made me think of the lullabies I would sing to my children and how that’s also an exercise in naming and describing things, and everything that comes across. I think it’s a very simple yet extremely direct way of engaging with your story.

Katia Motyleva: The poem is an important part of the project because it was written by my friend with whom I grew up. Now, from time to time, we check on each other. She has her whole family in Ukraine, and I’m here. She has a son, and I have a daughter. So we have a parallel situation and can sometimes discuss what is happening and how we experience it. She is also a poet. She writes poems, and I do imagery, so that was a match in the sense of talking to each other for years and years, and it was easy for her to relate to me and write this text about food and the history of Ukraine and its famine, the Holodomor. There was a lack of food, and many ailments were forbidden. People had to change the names of certain dishes because they were politically censored or you couldn’t make them. That brings the story of the still-existing oppression related to food and how we managed to pass on culture through it. So this poem was translated from Ukrainian to English, and I think she found very good words to convey the experience of my imagery.

*********************

EM: Do you feel that all you have been experiencing in the past months is changing the way you address your practice?

Lia Dostlieva: My practice became more detached over time because I feel I started earlier. For me, war began in 2014, and that marked a shift in my practice – that was when I started to create critically. I’ve been in this situation for ten years, and I’ve been told in the past by people inside my own art community – people who were unaffected by the war back then – that I’m too emotional and too traumatised.

And then everything shifted to the next level, so maybe there was also a change in perspective, just like the inner hierarchy of who is allowed to speak about what? So I think I got a bit tired of this emotional exposure, and for the Venice Biennale, I made something very detached, research-related, not related to ourselves at all. And I received at least three media requests for interviews with questions like, ‘Oh, your practice used to be so personal, and now it’s become so detached and cynical and some humour is even involved. Why?’ And I was like, people, are you supposed to be kind of paying attention? We were always working like this. But all projects except the most personal ones were ignored because it’s easier to talk about emotions when it comes to women’s art; it’s easy to frame women as emotional and dramatic when they’re speaking about personal traumatic experiences. It’s a particular framework, a very specific role we’re talking about. And if you're doing something else, then it's more complicated and less comfortable for audiences and critics. I got tired of this super personal perspective, but recently, on my way back from Ukraine, I made a decision that’s totally the opposite of what I’m saying now. I started to work on a super personal project. So, for me, it’s always like this in between. I simultaneously like being super honest and talking about super personal stuff and also try to keep this position as a cultural anthropologist. So it’s probably fine. It’s just kind of different layers of me.

*********************

EM: With In Pieces, you all engaged in a very powerful and brave act of vulnerability, exposing so many aspects of your own experiences, which are still ongoing and have been going on for years, since before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. How do you feel now, seeing this object navigate the world? Do you feel that this allowed you to address those difficult conversations that were there at the beginning of this project, or do you feel that it exposed more complicated nerves and complicated aspects that are hard to navigate?

SB: I always refer to this work as my most personal work so far. I never work with such personal matters, and these conversations and chats were always part of my life but never part of my practice. Now, I feel very empowered by this kind of crossover in which something very personal, which is around me all the time, becomes accessible to my audience through my work. Since the beginning of the invasion, I’ve had these switched experiences: maybe I’m having a conversation, a presentation, something completely casual where I’m talking to any of you, and then I switch. I turn my phone to check the time, and then I might have a message, or the preview of a message on the screen, with only a few words – which can destroy me. You don’t know what happened yet, but as soon as you see it, something breaks inside you, and it’s very difficult to communicate it to people around you. It’s very painful and you can’t really express or explain to them what happened, what’s wrong. They perceive something is off, but then they don’t know. So this was also the intention of my book. These images are a bunch of noise, and they look very innocent. They don’t really bring much if you don’t correlate them with dates, which are sometimes very obvious. But then, if you spend time, if you kind of unveil this text, it shows how very personal it is, making you, as a viewer, extremely vulnerable because you did not expect it. And it comes from something about the war, about the troops, about the bombings, but also about somebody making food. And it’s what’s happening to me every day. It’s like somebody is making food, but also, the next day, somebody is being bombed. And I have to deal with both realities constantly. To be able to share these things and frame them in a way that lives outside of me helps me process things. I feel that allowing people to share experiences is important for both: for people who can recognise themselves and feel they’re not alone, and for people who have no idea what this feels like.

io ola lanko: Your question touches me. I do question how relevant this is. What are we doing here now, making this book, exploring this question through a very safe medium within a very safe environment while our parents, our friends, people we love are experiencing a very different kind of reality? Sometimes I struggle to find the strength to continue doing this, to believe that this makes sense or is needed or is relevant, and I keep constantly recalibrating. I’m here, this is my life, and I am trying to boost the trust that I’m doing something that might shed light on certain events or certain aspects. It’s not easy to maintain this confidence in making. Generally, for me, it aims to make sense of what is happening in very different ways. I feel like we’re deciphering. We're all deciphering the experience, trying to make sense of what is happening, of what is going on there. And we have our own different tools to do that, different visual strategies, different ways to connect the experience. We created this bundle, which is where the value lies.

I guess my personal vulnerability and the questions that arise are in the journey, in the heaviness and the lightness that I carry throughout the creative process. It’s my way of experiencing it, and it stays with me. But there is something beyond that individual experience and ability that I think is valuable in this work, that if it's seen through that lens of making sense out of those events, it creates points of connection for others to make sense of it. The contextualisation of this project is very important because if you lose that thread, then, yeah, you can go into a very different space. But I think we’re bringing the context in while also trying to reconcile the experience. That’s what we have. That’s what we can do here. There’s a lot of intensity happening in this project in many different ways, as it should – but I'm transforming it through the work, through feeling that intensity and raising the questions. Talking to my parents about this project while they’re in the bunker. It’s intense. And yet we’re here. And I still think that there is value to the work that can be extracted from it.

KS: I think vulnerability is one thing that’s constantly present if you're sincere in what you do, in every project. We had a certain luxury to be able to make this step aside and to look at it with a little bit of a perspective from the Netherlands, as we were not directly affected by the war. But I really feel that we managed to make it sincere, all of us. And what we tried to understand about ourselves was finally reflected in the book. And I think that’s the most interesting part because, of course, we’re all vulnerable at this moment. The book gave us space to talk to ourselves about what we could digest and how – in essence, what we felt about it. This project took longer than we expected, but I think that was also one of the benefits.

KM: In my project, vulnerability and personal experience became an artistic reaction to historical events and the documentation of collective experience. A little revenge for the long years of censorship in which Ukrainian women artists lived and could not speak up. Holding the book in my hands, work no longer feels overlooked or unimportant. My project is now published in a book, on paper. It gives me a feeling that my story is important.

******************

Hard cover with 5 artist booklets

Publisher: Growing Pains

Editors: Agata Bar, Zhenia Sveshchinskaya, Daria Tuminas

Design: Ayumi Higuchi

Images and texts by: Sophia Bulgakova, Lia Dostlieva, Ola Lanko, Katia Motyleva, Kateryna Snizhko

Poem Mother Tongue by: Lyuba Yakimchuk

Size: 25 x 35 cm

ISBN: 978-90-833635-0-9

Editor’s note: This is the second contribution in a series of four guest-edited by Growing Pains. Photography curator, writer, and editor Elisa Medde was invited by Growing Pains to moderate and write up this second conversation. The first one was a conversation with Susan Meiselas on how to inspire children to pick up photography.

Partners

-

Growing Pains is an Amsterdam-based initiative of Agata Bar, Daria Tuminas and Zhenia Sveshchinskaya, working at the crossroads of visual arts, publishing, conversation, education, and human connection that supports women and non-binary artists. The project navigates the space between artist books, photobooks, and children’s books, exploring alternative registers for difficult conversations. https://growingpains.nl/