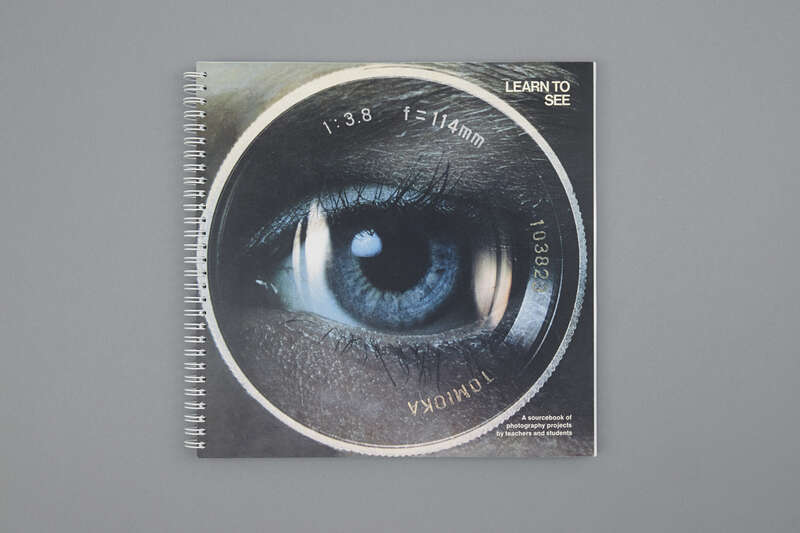

Susan Meiselas, Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers (2021, delpire & co, Paris).

‘I Can’t Wait to See the Photographs You’re Going to Make.’

A Conversation with Susan Meiselas on Books for Evolving Visual People

Zhenia Sveshchinskaya & Daria Tuminas

02 jun. 2023 • 26 min

What space can be created when photobooks and children’s books meet?

Growing Pains is a publishing initiative that operates at the crossroads of the two worlds. It invites artists to create new work made with a child in mind and facilitates its translation into printed form, an exhibition, and a series of activation events for young audiences and professionals. Growing Pains is committed to supporting women and non-binary makers and their stories. The initiative is founded and run by Agata Bar, Daria Tuminas, and Zhenia Sveshchinskaya. As their first publication takes shape, Daria and Zhenia have set out to map the already existing range of practices (from artistic to activity book approaches), meet makers, and zoom in on specific cases, weaving together the otherwise fragmented discourse.

Trigger invited Growing Pains to share the findings of this exploration in a series of texts. It kicks off with a conversation with Susan Meiselas, photographer, educator, and president of Magnum Foundation. Her exhibition Mediations is on view at FOMU (February 17–June 4), and she recently also guest-edited Trigger #4: Together, which deals with collaborative practices in photography.

Growing Pains spoke with Meiselas about her two books, published five decades apart, aimed at inspiring children to pick up photography and explore visual thinking to understand themselves and the world around them better. The conversation touches on the books coming out, the intentions behind them, their differences and impact, and Susan’s teaching experience. The text is structured in ten blocks according to theme: Revisiting, Gathering, Mixing, Object, Beyond ‘Me’, Age, Activation, Teaching, From Within, and Understanding. We’re publishing it here for all who consider themselves kids and visual people in progress, always up for learning how to see.

Susan Meiselas, Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers (1974, Polaroid Foundation).

REVISITING

Growing Pains: In the seventies, you were a teacher in New York’s South Bronx as well as an education adviser to New York City. In 1974, with the help of other educators and the support of the Polaroid Foundation, you put together Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers. You must have felt that the publication and its approach haven’t lost their relevance, because in 2021 you reissued Learn to See (delpire & co, Paris) and put out a new book, Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids (Aperture, New York, and delpire & co, Paris). Why did you feel the need to revisit one book and create another, both within a year? And what were the differences in the approaches and visions of the two publishers who worked with you?

Susan Meiselas: It’s interesting that you put it in the framework of revisiting. I appreciate that because I think most people don’t. First of all, very few people know about the 1974 book or the fact that I taught in a primary school for the first four or five years of my career, at the same time I was actually producing Carnival Strippers, which may seem like a surprising double life. Learn to See really evolved from teaching and not knowing what to do with photography and kids. It was a very genuine instinct.

I built a darkroom in the classroom, and then began to work with Polaroid film. Polaroid was very generous as a company, offering opportunities for many teachers in different settings and working with different age groups to experiment with their products. When I got the equipment, the cameras and films, I began to think about what I could do with the kids.

Halfway through that period, I, in a somewhat innocent way, wrote to Polaroid, thanking them for the equipment and asking, ‘What are other people doing?’ They had no idea. And that’s really what motivated me. I got the list of all the teachers they had given cameras to and wrote everyone a letter asking, ‘What are you doing?’ I didn’t use the word ‘collaborate’ (‘Please collaborate with me!’). That word has become part of my vocabulary more recently. But in that early stage, it was really just gathering, trying to learn from others, and sharing knowledge. It was a sharing incentive. As people would send me things, obviously some projects were more interesting to me than others, and I gradually conceived this sort of sourcebook of inspiration.

It was never intended to be a recipe book, or a how-to book (which is why I struggled with the Learn to See title). When Polaroid published it, they were thinking about their own use for it as an educational marketing tool, no doubt. It was both gifted to teachers and sold openly. I have never found a used copy of that book, which is amazing. The run was probably 10,000 copies, and there was only one printing. I was so young that I didn’t even keep more than one copy myself, so I only made an effort to find them much later – and I could not buy any! Different people have written to me over many years asking for copies too. In some ways, that’s what motivated the revisit.

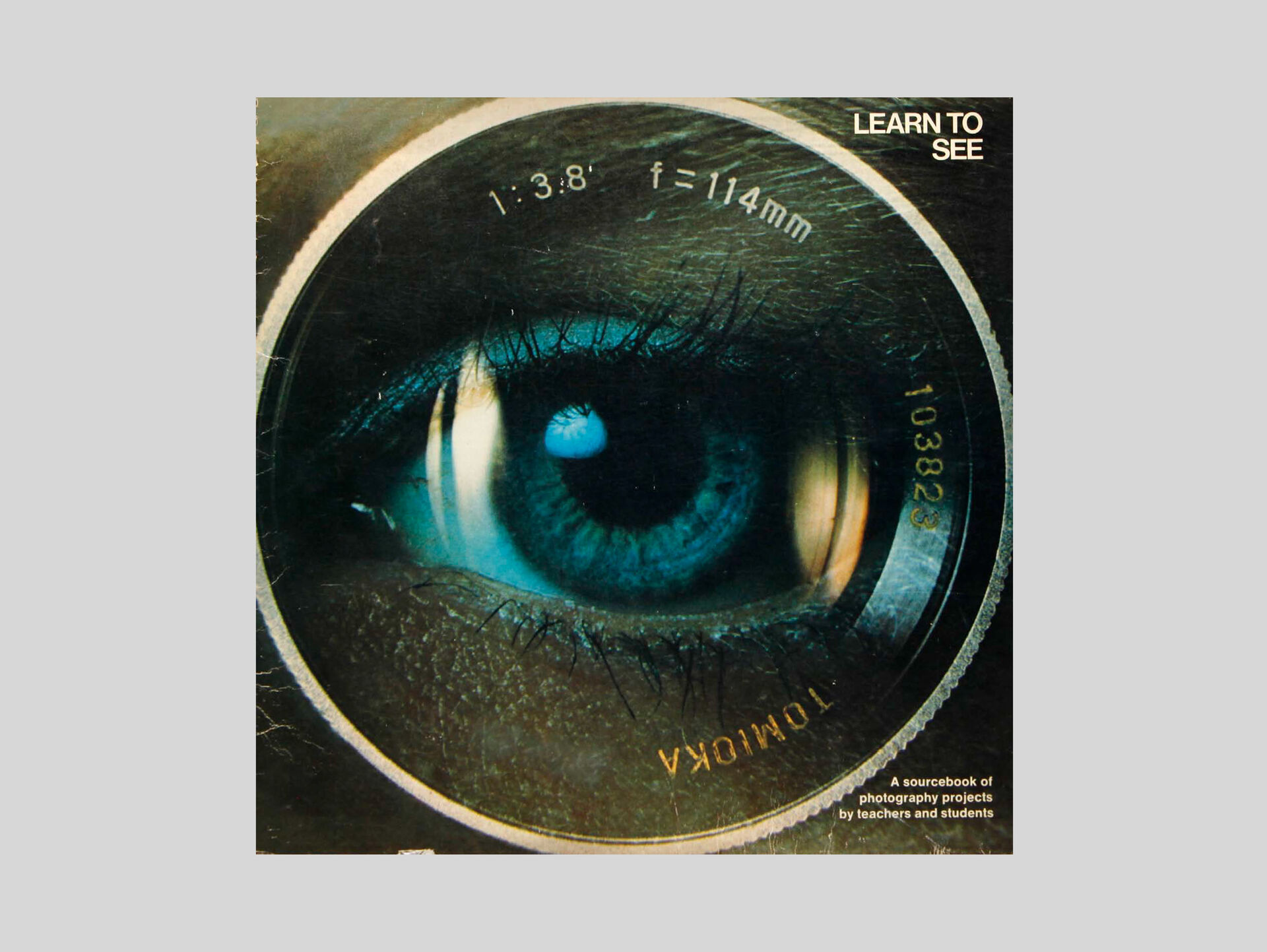

Susan Meiselas, Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids (2021, Aperture, New York).

And then Julien Frydman at delpire & co saw it as an object and just said, ‘I love this. I still think it has a lot of value, and let’s just reproduce it exactly as is.’ He understood the book’s role in the history of photography. So the one original copy I had went to Paris, and they reproduced it really well. Of course, I didn’t have any of the original photographic materials, so a facsimile like this you could only do in a digital age. delpire & co took all those pages out from the spiral binding and rescanned them at high res to reproduce the book. They made a very small run of 500 copies, which is practically sold out. Meanwhile, Aperture had a different mindset: they’re looking to make new books. They don’t often republish, unless it’s their own old books – they’ve reprinted my book Nicaragua, for example.

And there’s a tangential but meaningful connection, which was that Denise Wolf, who leads education publications at Aperture, happened to have gone to the school where I taught in Rock Hill South Carolina many decades later. So she knew about Learn to See as a young person. For many years Denise said to me, ‘I wish I could reproduce Learn to See.’ And I kept saying, ‘Well, you know Polaroid film doesn’t even exist anymore. Why would we do that?’ And then as the internet developed, there was this question: Could you do something in a more interactive space via the internet to invite people to participate? After making the multimedia project Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (1991–2007), which included akaKURDISTAN, as a website collecting photographs, videos, documents, and oral accounts by Kurdish citizens, I could not imagine the management of a new project. I simply said, ‘No way. I’m not doing another participatory website.’

She kept coming back to me, and eventually I said, ‘Well, maybe there’s a whole other idea of something we could do that would be a kind of revisiting, but more as a contemporary reading of our culture today.’ So Eyes Open is a response that begins with literally looking through Learn to See and considering which projects would be appropriate to engage in the process of visual literacy today. Then we invited kids to respond to those projects or add new ones. The drive was to animate and engage people again in the process to think about what they are photographing. What can they do today with cameras differently than we could do with Polaroids then?

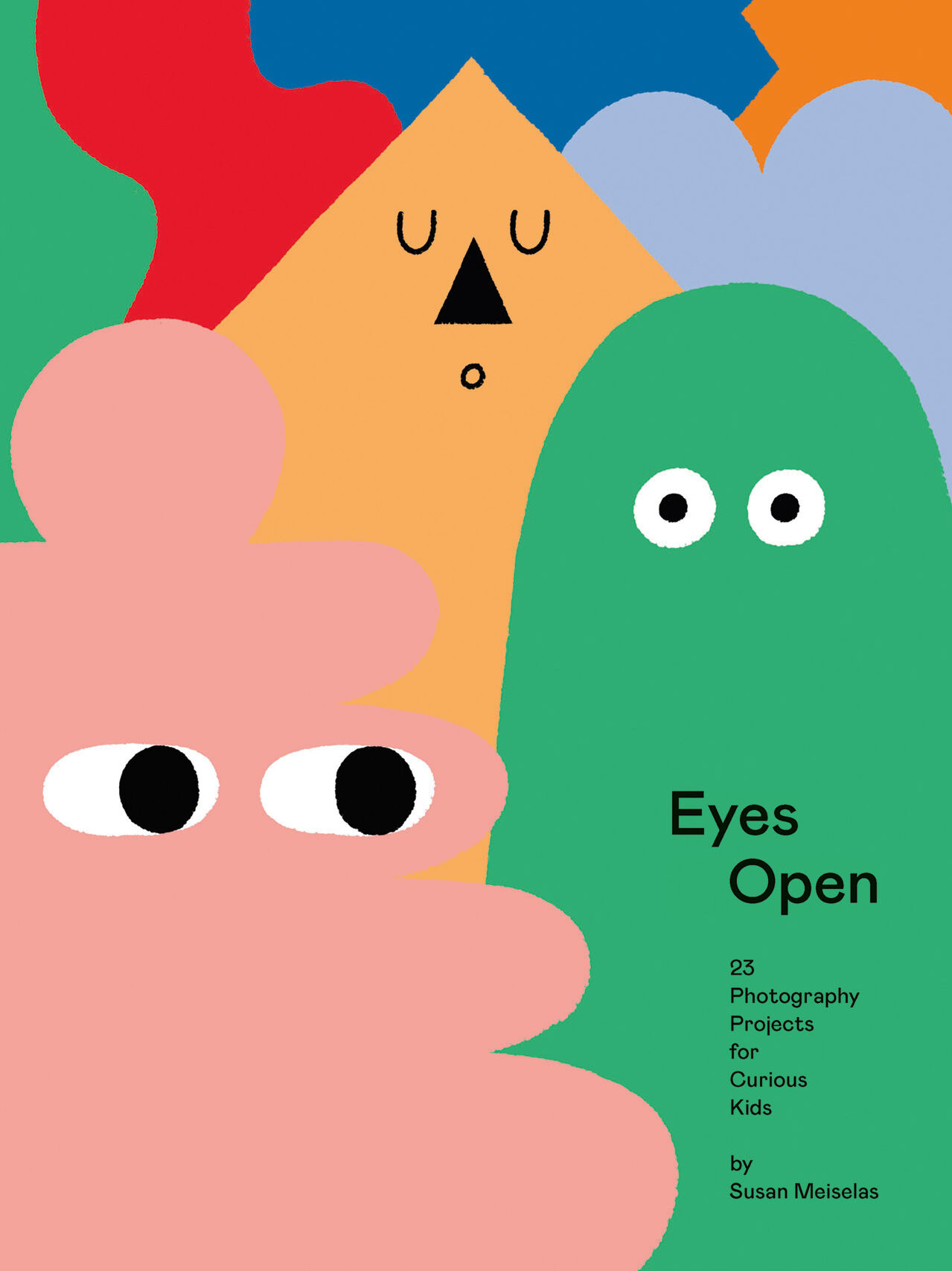

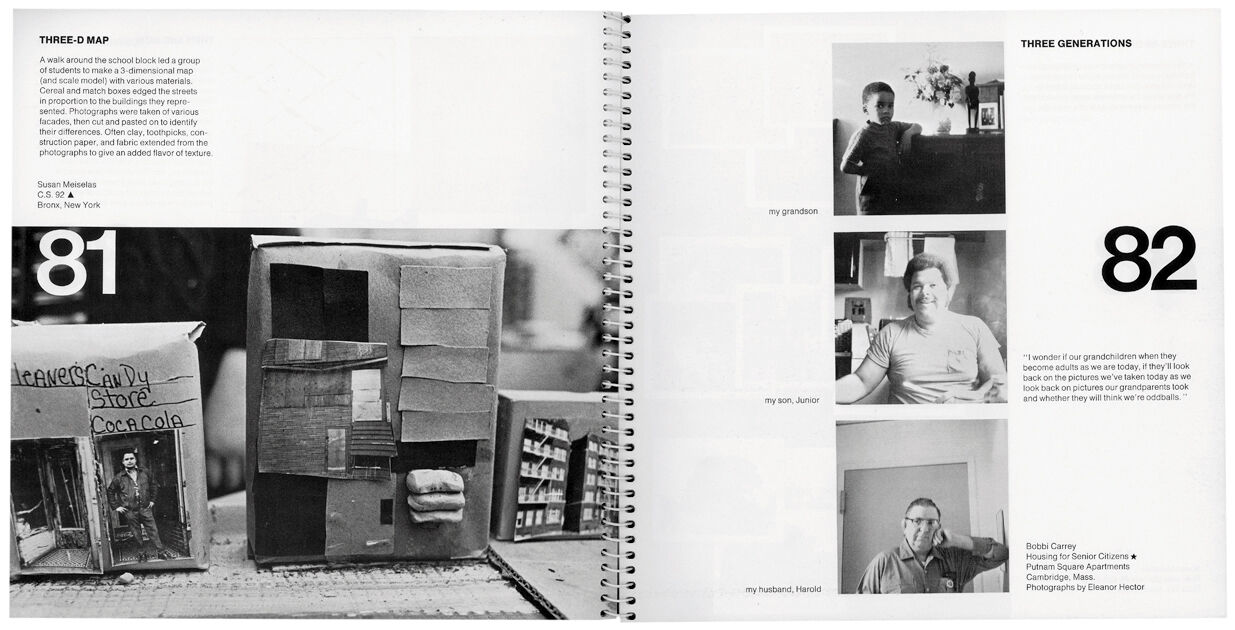

Susan Meiselas, Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers (1974, Polaroid Foundation). With work by Ray Bisaillon.

GATHERING

Growing Pains: Eyes Open evolved over time through an outreach initiative that brought together people engaged in teaching photography in a classroom or an after-school program. Over 200 teachers from around the world gathered and shared the work of over 400 children. How was this process of gathering and selecting images happening, and how did it differ from the process of gathering materials for Learn to See?

Susan Meiselas: With Learn to See, I just got envelopes from people sent in the mail with little bits and pieces of things – puzzles to try to put together. I had a wonderful designer, William Field, who created a way of seeing all the 101 contributions equally, which I loved. We invented titles that would allow the materials to be visually diverse and then simply gave each a number and indexed the themes in the backmatter.

With Eyes Open, we sent out digital packets to over 200 teachers to see which projects in particular would be exciting for them to see, knowing that they didn’t have the whole book, and what might continue to be relevant. I wasn’t encouraging mimicking as much as giving them a framework to understand the way we had thought in the early seventies about visual education. I began to see certain concepts in their responses that I myself, as a young photographer, hadn’t really learned, which is something I often think about when I see contemporary photographers’ work. The work the kids were doing was clearly impacted by exposure from beyond the classroom, from what they had seen in exhibitions and books and online. So what I wanted to do was imagine this 360-degree world of today where kids are seeing work from many different kinds of sources. With the internet in particular, there’s almost confusion and a fusion as well. I wanted to come up with a concept for a book that could really encompass all in response to what I was learning from and with kids about how visual culture functions for them today.

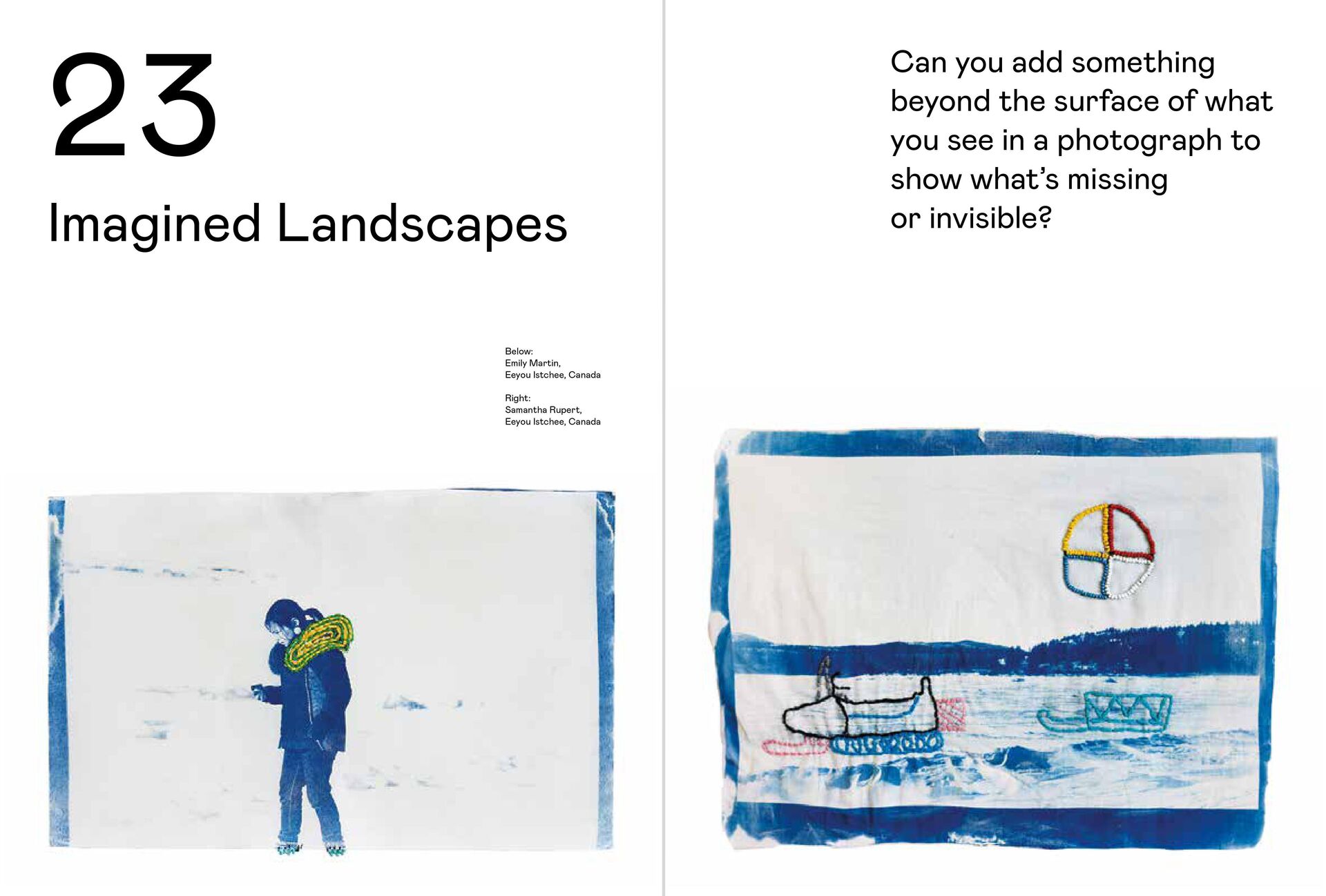

Susan Meiselas, Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids (2021, Aperture, New York). Works by Emily Martin and Samantha Rupert.

With Eyes Open, I had a strong research team at Aperture. I can’t imagine having done it without them! My nightmare about doing such a book was that I’d be overwhelmed. I knew that if we reached out to 200 teachers, each of whom would have x number of students who might respond, it would be a lot to manage. The Aperture team gathered all the digital files and prioritized material that they thought would be most interesting to me. And then we all went through a series of revisits to see what kind of content we were getting globally, narrowed it down, and then finally figured out the structure and flow.

When I was doing Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History, we didn’t have digital tools in place yet, except Quark, which we used to design the book in my studio. So between Dropbox and Excel, Google Sheets and all these new collective collaborative tools, including Zoom, we were able, during Covid, to still continue producing Eyes Open. It would have been impossible before that. I have screenshots of us sharing, looking at different possibilities both during the design process and before that, just looking at phenomenal amounts of content together. This book was much more co-curated than Learn to See.

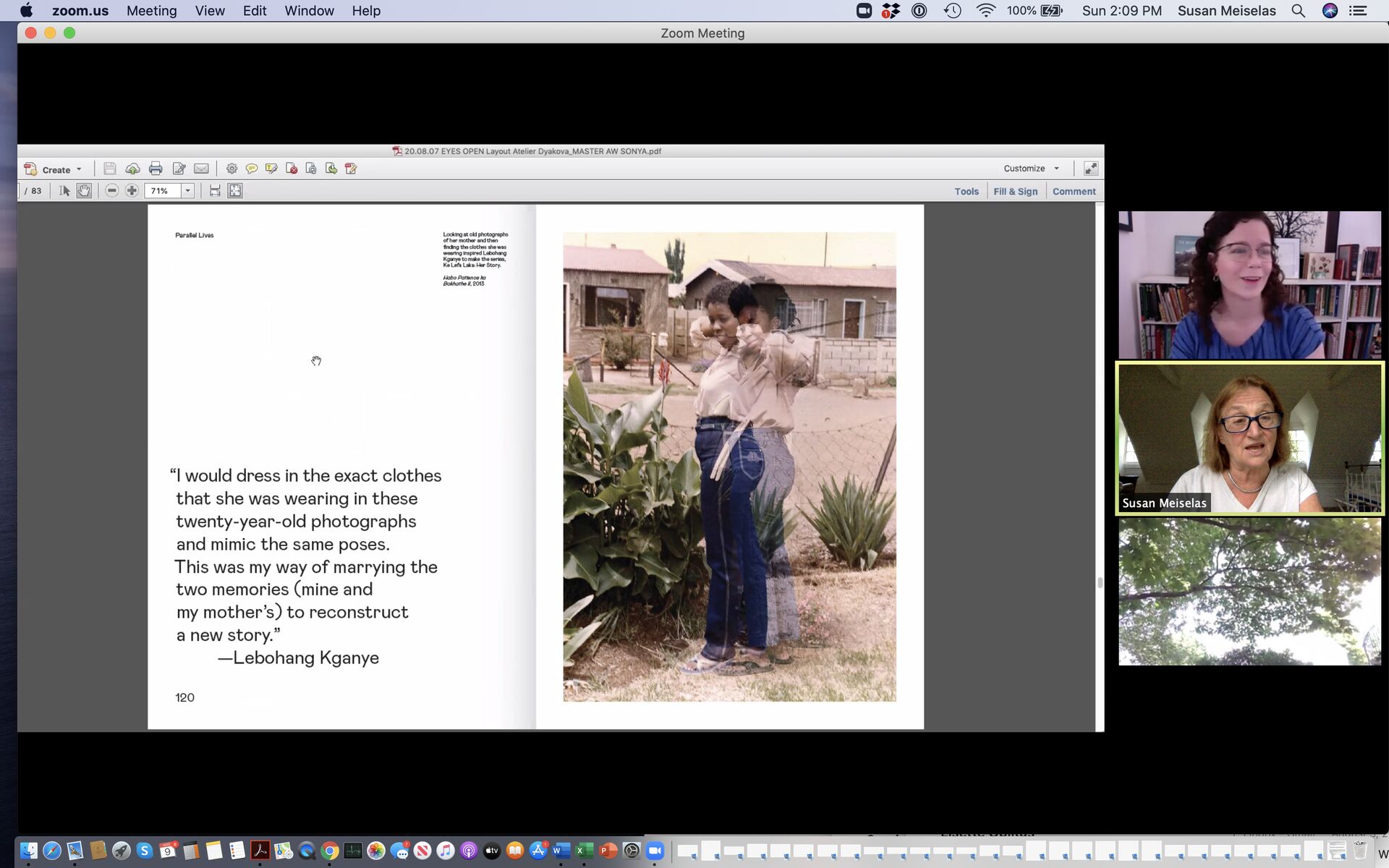

Online meeting: Susan Meiselas and Denise Wolf (8 September 2020). Discussing Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids: the layout with work of Lebohang Kganye.

MIXING

Growing Pains: Learn to See included images produced by children and teachers’ prompts. Eyes Open includes photographs by kids from around the world, mixing them with works by established artists (among them Zoe Leonard, Rinko Kawauchi, Sally Mann, Jim Goldberg, Lebohang Kganye, and Cindy Sherman) as well as selected quotes about their practices. In the first case, there was a multivocality of educators present, and in the second, a multivocality of makers: the uniformity of design gives the same platform to both beginning and mature artists. Could you please speak about these choices and differences?

Susan Meiselas: The design of Eyes Open is a format that’s not trying to distinguish the children from the artists. It’s really trying to say, ‘We are all evolving visual people.’ And I love that there’s a mix: sometimes it’s the work of emerging artists, sometimes they’re artists who are more well known, and they’re both interweaving with students who are being published for the first time.

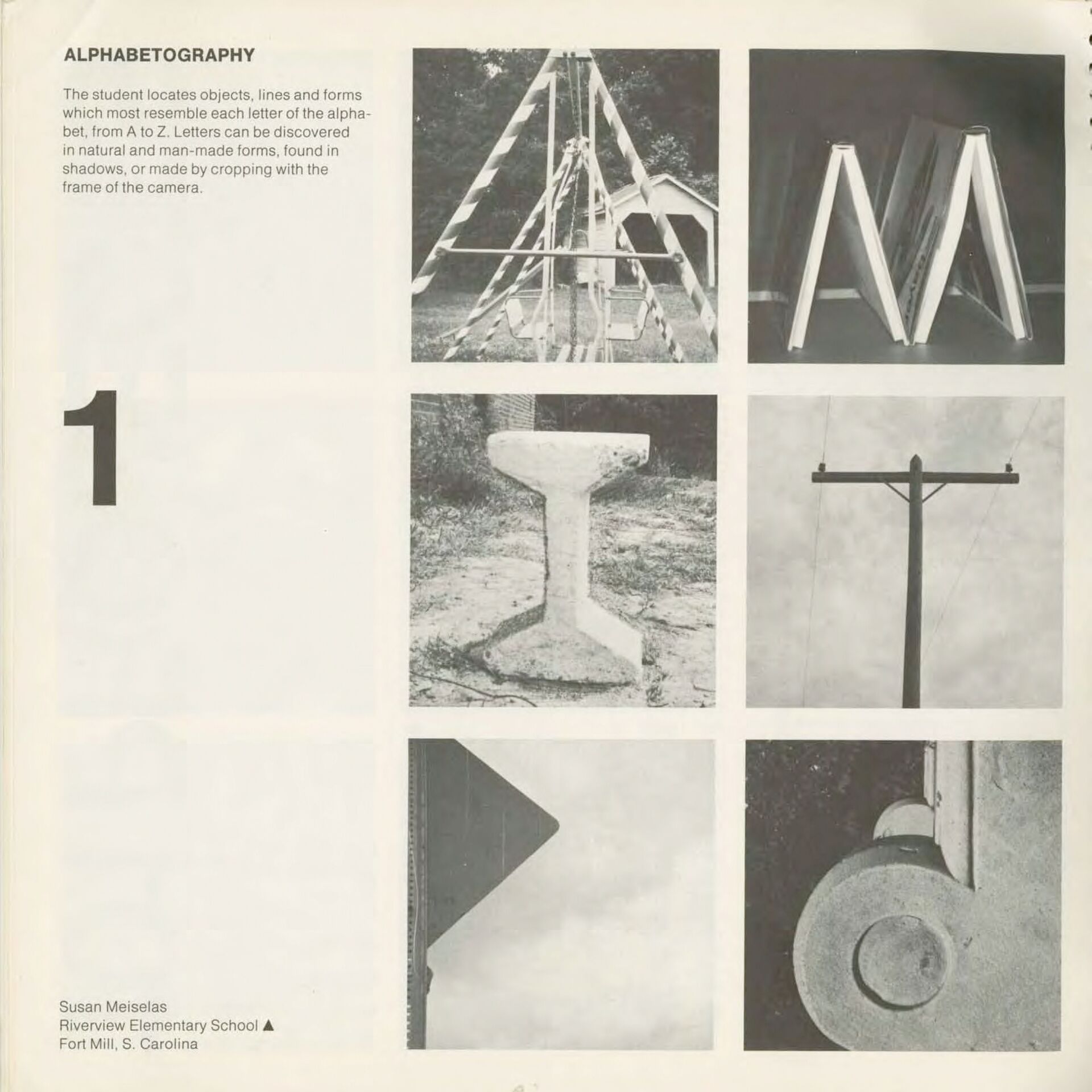

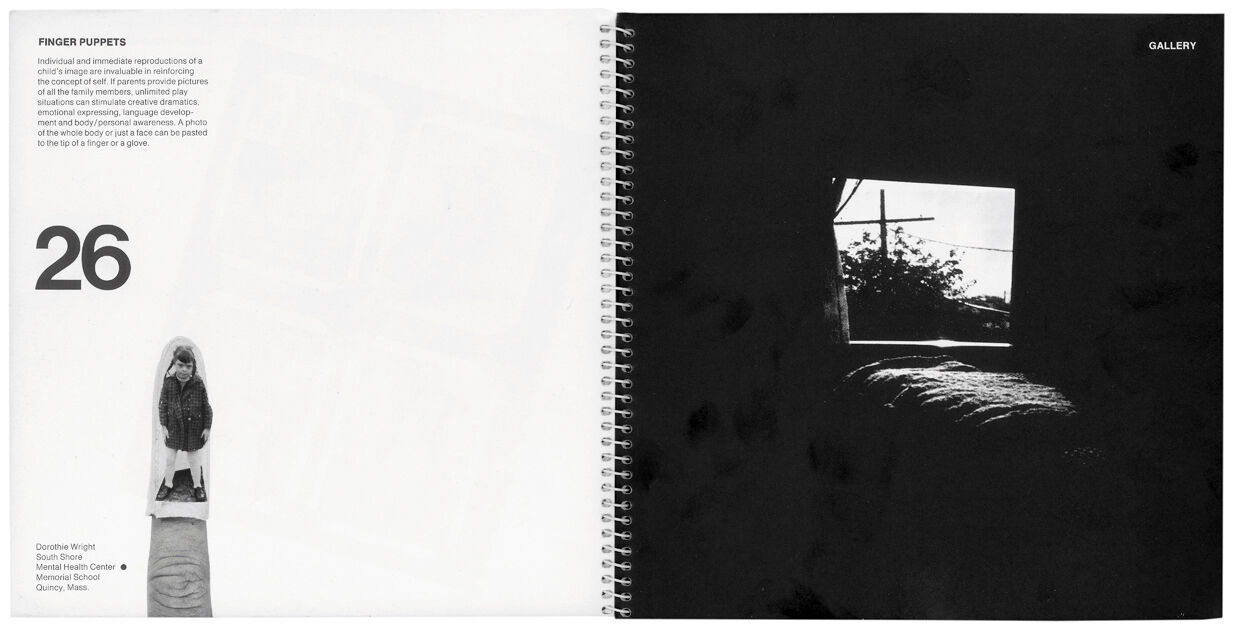

Susan Meiselas, Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers (1974, Polaroid Foundation).

We can talk about combining and selecting works through the example of ‘alphabetography’, which opens the book. There are many artists who have thought about the alphabet. I started with Wendy Ewald – she’s the only person in both books, and she’s been a teacher most of her life. I knew the Arab and American alphabet projects that she had done. I looked to include others – Lee Friedlander and Ed Ruscha being two of the many other possibilities. But I was limited by pages, and therefore each time I had to be very pragmatic with limited choices. In some cases, I was able to have more than one artist or student represented.

When I worked on Learn to See, I made all those decisions: I wanted each of those 101 projects. And in the case of Aperture, I was given a framework within which I had to work. Eyes Open had to be very accessible and fit into what Aperture sees itself doing. There were some constraints, essentially, on how many projects we could fit in to the page count.

The really important idea around Eyes Open is the change in our culture – this notion that kids see so much now, so much more than we were seeing fifty years ago as young image-makers. How did I see what I saw? There was very little visibility for photography then. In the early seventies, in New York City, what would I have seen? There were very few galleries. There were almost no exhibitions. There were very few publishers. If I didn’t travel to England or France myself physically, I wouldn’t have seen many photobooks or met the community producing magazines like Camerawork and Ten 8. There was very little international distribution then. Now we’re in a world where the sources of images are not even clear. How can kids separate what they’re seeing, be it in books, on television, in advertising, on Instagram, through their iPhones. They must be overwhelmed with all the mixing of visual material. So all the elements of the visual world become equal. All of this is fused, and probably confused – I think it’s both. There are no boundaries, no borders. And I come from a different tradition, where for me there are distinctions: I do want to know if this is a documentary, a more evidential image, or if we’re seeing a constructed or re-enacted one. Those concepts are still really important for me to distinguish. In Eyes Open, I’m trying to open up the visual vocabulary to what I know culturally is current, which isn’t only my practice, but it is the practice of others. I was trying to embrace as much range as possible, which would be a mirror for what I know kids see today and help them find their place in that spectrum of possibilities.

OBJECT

Growing Pains: Let’s reflect on the apparatus of photography and how its importance changes in the two books. There’s the instantaneity of the Polaroid underlined in Learn to See and the immediacy of the digital image-making of today in Eyes Open. This shortcut from looking or seeing to having an image seems to be important in both instances. Despite the fact that technical understanding is not necessary for using a Polaroid camera, in Learn to See, you talk about the importance of explaining the workings of the camera to the students. In Eyes Open, however, the technical aspect of image-making gets no mention. Can you talk about this difference?

Susan Meiselas: I think Eyes Open does build in concepts that are important to photography, such as light, movement, and frame, though it’s not specific to one apparatus. In Learn to See, it’s mostly Polaroid, but there were some projects using analogue photography. Kids were making pictures with whatever cameras they had at that time, and we didn’t teach the lens and the shutter with the Polaroid, only with simple point-and-shoot cameras. Most people have no idea how an iPhone actually makes a photograph. But principally, light, frame, time, movement – those fundamental ideas – are embedded in Eyes Open in a different way than you even think about them in Learn to See. What is being learned is not so much about the apparatus, nor about photography per se. It’s about the experience of how photography brings you into the world and helps you engage with the world and with your own ability to observe, think, and understand things.

I always thought about the Polaroid like a daguerreotype. The photograph it makes has always been very precious: you have the capacity to give something immediately, but then it’s gone. Digital does not really necessitate giving anything up at all. You can immediately show somebody the picture you’ve made. You can send them the file. They print out their own picture. When you gave a Polaroid, as the kids were doing then, that meant giving their pictures away to the plumber or the butcher down the block. That was a big moment for them!

These are aspects of photography that I would love to have found ways to talk more about, but I don’t think it’s really in either book, questions about what the apparatus produces, or what photographs can do in the world as objects.

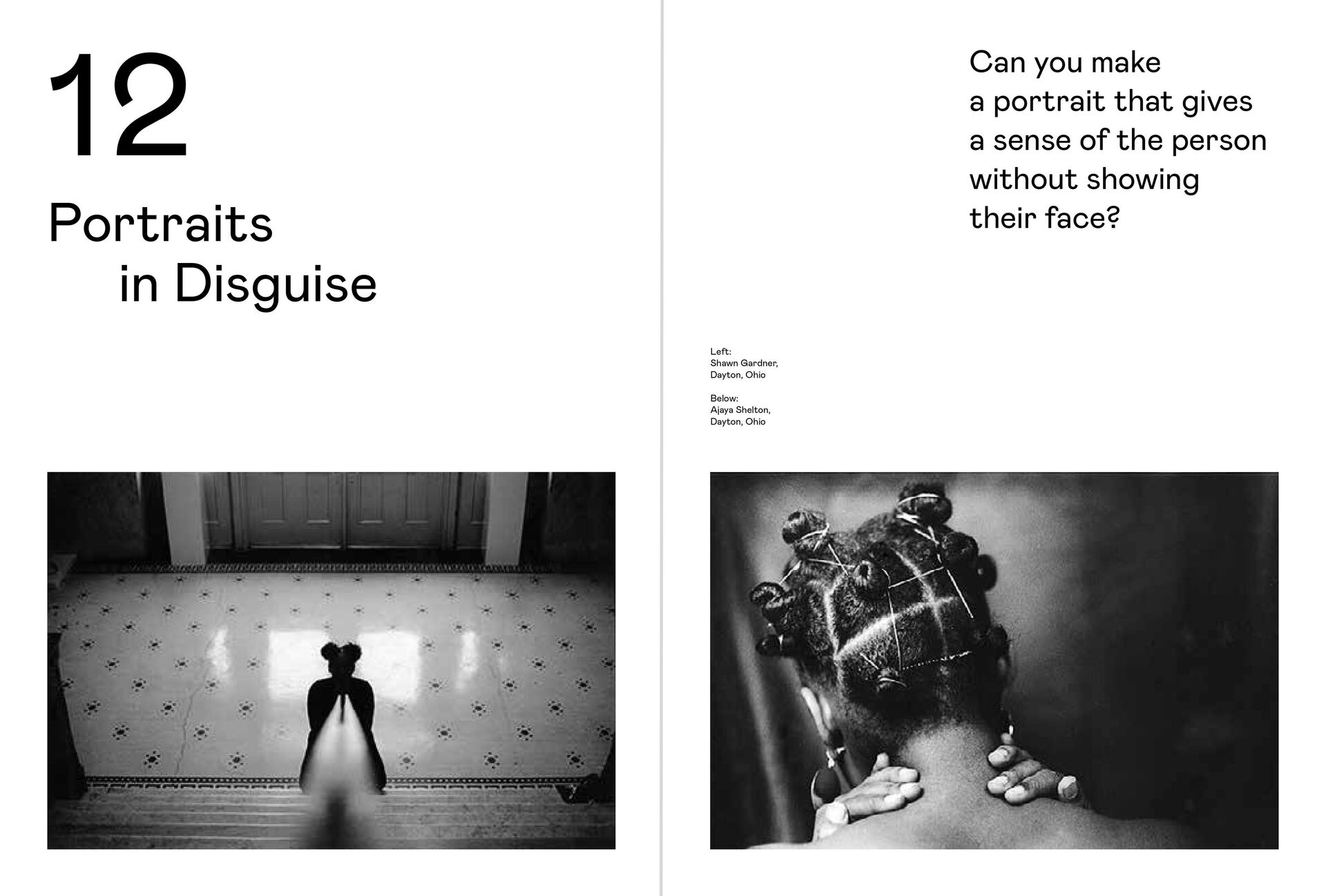

Susan Meiselas, Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids (2021, Aperture, New York). Works by Shawn Gardner and Ajaya Shelton.

Susan Meiselas, Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers (2021, delpire & co, Paris). With work by Dorothie Wright.

BEYOND ‘ME’

Growing Pains: In the text published by Magnum about Eyes Open, you say, ‘The culture of the iPhone has generated a self-orientation versus an outward-looking, engaged process of observation.’ But selfies and self-oriented lenses are so much part of the daily routine for kids now. The book chooses the strategy of not, perhaps, reclaiming this genre or finding ways to build on this visual culture, but rather proposes stepping aside from it. Can you elaborate on this choice?

Susan Meiselas: I see that iPhones are often used almost like diaries. And the selfie culture is of course about ‘me’. There’s a lot of ‘me’, and then there’s ‘the other’. How does one bridge from ‘me’ to ‘the other’? Kids are particularly oriented toward ‘me and my friends’. Even much more so than their families. The Portraits in Place project is about ‘me’ in a chosen landscape. That’s trying to begin a progression beyond just ‘me’. I’m trying to find ways that kids can progress from ‘me’ to ‘me and the world’ – and then be more excited to look out at the world. The sequence is creating an evolution towards a way of thinking or experiencing the world. And yet, the book is not designed to only be followed page to page.

How can the kids become observers in the world, and look at their families and see distinct gestures, and not just ask for or always expect the performative? Of course, there is a natural performative instinct and invitation from a camera, but there’s a difference between inviting the presentational or performative and moving towards a more observational, reflective eye.

My bias is to shift them away from thinking that the selfie is the only thing they’re inspired to do. I feel the book would be a total failure if that was all that kids found themselves doing at the end of looking through it, and don’t want to experiment with different vantage points. I don’t want to tell them how to do photography, but I want to give them a pathway towards expanding their own vision. Not just from an evidential perspective, but also from an imaginary space that can be conceived. If a kid is oriented in one direction or the other, that’s fine – there’s a spectrum to inspire them to explore.

Susan Meiselas, Learn to See: A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teachers (2021, delpire & co, Paris). With work by Dorothie Wright. Works by Susan Meiselas and Eleanor Hector.

AGE

Growing Pains: Learn to See is aimed at all ages, from preschool kids and up to pre-college and elderly. Eyes Open is specifically addressed to children aged nine to twelve and older. How were these age categories defined? Were they proposed by publishers? Were they clear to you from the start of the process of working on these books? How did this age definition affect your making of the publications?

Susan Meiselas: Learn to See refers to different classrooms. So the class could have been an elementary school classroom, high school classroom, college classroom, whatever. The book has geometric symbols to indicate appropriate ages. That was my visual code to give teachers a guideline for what they thought their kids could achieve. For Eyes Open, that was a marketing issue for Aperture. As a publisher, they were very clear that when you send books to a bookstore, you have to position the book somewhere.

Where is it? Is it in the photography section, or is it in the children’s book section? Once it’s in the children’s book section, it changes if you’re looking at adolescents or younger age groups. Maybe they’re two groupings, and maybe they’re three, with young adults. Publishing has all these categories that books have to fit into. That also becomes important when you produce your press list and people start to order – if a librarian at a school is going to order it, or the public library, and so on.

I also know people who have told me that they bought the book for their kids, and that they like doing projects with their kids. That’s a wonderful way Eyes Open functions that we didn’t really think about – the parent-child relationship. Learn to See was more aimed at the teacher-child relationship. But Eyes Open is much more about the ‘older kid’ and the ‘younger kid’, or a parent and a child, or parents who want to discover photography themselves. Most interesting to me has been meeting people. For example, at Paris Photo, people said, ‘I bought this for my kid, but I’m using it myself!’ or ‘No, this is for me, not my kid!’ when they ask me to sign it. You only discover over time how books get seen.

ACTIVATION

Growing Pains: Can you share with us some of the occasions for engagement with Eyes Open by kids that gave you a sense of how it, as an activity book, facilitates these activities, and sparks creative processes?

Susan Meiselas: There was one very sweet moment that gave me a feeling of how the book was living in the world beyond what I’d imagined. I received an invitation from the Whitney Museum of American Art to contribute to their free art program during Covid. So Aperture and I organised an online session: Open Studio from Home: Book Party with Susan Meiselas. I spent two hours with this group of kids that ranged from five to twelve, introducing the book. I took one prompt that they could all do during Covid when they were stuck at home. It was the mirroring idea: when you see a painting, and then you act to mimic the painting.

Laura Protzel, who coordinates the Whitney Family programs, and I started by choosing paintings from the Whitney collection. We found ten to twelve paintings that had a visual range, whether famous or not. We were looking at their visual structure. Once we were online, I asked the kids to choose one painting that they really liked and wanted to think more about. I started with, ‘Do you have a place in your home that has a table, a chair, a mirror, a curtain, or whatever you’re seeing in the painting you chose? Find the place in your apartment where you could make a picture with that object!’ They went off, scrambled around, and sometime later, when they had found their place, they came back. And then I said, ‘OK, now look at what’s happening in that painting. Is the person sitting? What are they doing? Look at the gesture they’re making. What can you do if you position yourself in the potential photograph?’ And then the next thing was, ‘What are they wearing? Do you have anything that relates to what you see?’ There were these three levels of observation to get them to both see the painting and then mimic or invent themselves in the photograph.

At the end of that, they all came running up with their iPhones and showed me the pictures that someone had made of them. It was one of the most extraordinary moments I’ve ever had teaching. There were sixty to eighty kids online, from twenty-nine states in the US and eighteen countries around the world! I was desperate to be able to document the grid of their faces and pictures, but due to privacy concerns, it was against the museum’s policy. So it’s just my memory of this extraordinary moment of these kids being absolutely on fire making discoveries for themselves in their homes in relation to a painting they were seeing for the first time. It was really fantastic.

Susan Meiselas teaching elementary school student, South Bronx, New York, 1972. Courtesy Community Resource Institute.

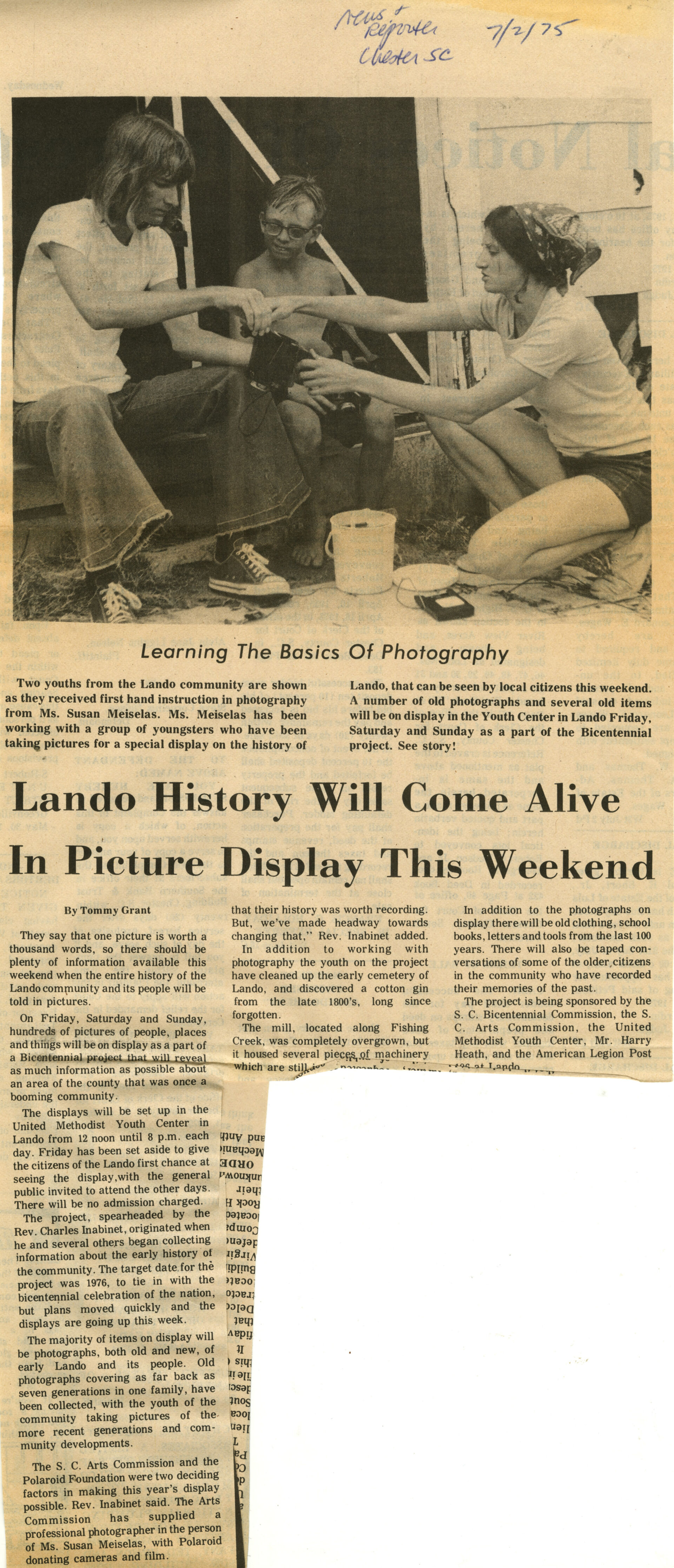

Newspaper clipping from Chester, South Carolina, Lando History Will Come Alive in Picture Display This Weekend, July 1975.

TEACHING

Growing Pains: That was also so 2021 – connecting via Zoom, and making such a meaningful experience out of teaching and this exchange. But let’s return to the seventies. What and how were you teaching then?

Susan Meiselas: I was tasked to be a visual consultant for the Community Resources Institute based in New York. I was teaching kids storytelling using animation with eight-millimetre film. I loved it even more than photography, because those were invented, fictional stories that kids created by cutting up construction paper. They would imagine a landscape, and then create characters and animate with stills as they moved their characters across the scenes they had hand drawn. Each student made a short film of their story.

Then I started to do photography as well in some schools. In a few of them, I built a darkroom. I started in one classroom (which had fourth, fifth, and sixth grades combined), and then the institute had me teach other classrooms as well as other teachers and even parents. A few years later, I went as an artist-in-residence in South Carolina and Mississippi to teach in several elementary schools.

I was using photography really to teach the most basic learning – between the alphabet with words, to sentences and then ideas. How do children learn to speak and to read? ‘Read what you see and say’ was a very important technique. You take a kid outside, they make a photograph, they come back into the classroom, and you say, ‘So what’s this picture of or about?’ It’s very easy for them to tell you. If you ask them to write about it, they don’t know where to begin. Actually, I’m not that different from them! If you asked me to write about all this, it would be a tortured session, versus finding a way to talk about it in response to your questions. It has a different flow. The kids would tell me, and I would listen. I would capture their words, and then they would write their stories from what I heard them say. Then they learned to read what they’d told me.

FROM WITHIN

Growing Pains: In the seventies, as you mentioned, there were not so many photobooks available to bring to a class. But in your more recent teaching experience, have you been sharing some printed matter examples with your students? Maybe to go beyond single images and talk about visual narrative?

Susan Meiselas: I know people do bring photobooks to their classes. And you both might remember when I was teaching you both in the master’s workshop at Leiden University. Bas Vroege and I had a somewhat different approach. I would much prefer a student stew and not know what to do. Bas would sometimes say, ‘Why don’t you do this?’ I feel like the only real work is the work you commit to, because you have your own curiosity and passion to pursue it. My inclination as a teacher at the highest level, or even at the lowest level, is not to bring in references but rather to ask questions, to create frameworks for kids or students’ own exploration or experimentation. That’s John Dewey’s learning by doing – a very fundamental concept. You can respond to what somebody else wants you to do, and you can do it very well. But if you’re going to have a life in the work of making, it has to come from within, in response to yourself or the world – but it comes from the doing.

But, of course, it depends. I was invited to teach in Abu Dhabi, maybe ten years ago, after I had published Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History. I worked with a group of young women who were segregated, gender-wise, in art college. They were inspired to do something in response to my book, which they had seen. They began to collect their family albums from the Emirates, which had not been done before. They definitely took certain ideas they saw in my book, but they adapted and elaborated on it. And their book was from that inspiration but unique to their experience.

We now live in such a different universe. I’m meeting students internationally, and I’m very aware that they don’t need physical objects as references. They just search and float on the internet, and they don’t necessarily know the source of the things they see. Maybe this surfing the internet is the doing before the making – maybe that’s their ‘doing’ process.

UNDERSTANDING

Growing Pains: When we (educators, artists, publishers) engage in creative education practices, we vocalise goals and some sorts of results we want to achieve. However, this kind of practice doesn’t lend itself well to quantitative or qualitative analysis. What are the ways to understand and assess these educational practices and their successes and challenges? How do we look back and understand what we have done?

Susan Meiselas: I don’t quite know how to respond to that question. I can’t find one copy of Learn to See on eBay or AbeBooks, and that tells me something about the fact that it’s valued, that it’s still something that people hold onto for whatever reasons. And who did that, exactly? I don’t know, because you never know who buys a book. Who saw the book then? Who gifted the book? And what’s the so-called measure of success when these metrics are impossible to trace?

A reprint of a book is significant, because it’s a publisher making an investment based on their ability to assess a market. The fact that both English and French versions of Eyes Open are in reprint tells me that there are people buying the book who want to use it to inspire their kids or themselves.

After many decades of teaching, I remember only one kid, Ricardo, from the Bronx elementary school, who came back to me maybe eight or nine years ago and said, ‘I just want you to know how important it was in the fourth grade that you were my teacher!’ He became a landscape architect. He was Puerto Rican, and his parents didn’t speak English, so visual storytelling opened up the world for him.

I can give you another example. What’s this measure of success? I was doing a book signing for Eyes Open at the Magnum Gallery during Paris Photo. There was a six-year-old who came up to me. His father had just bought him Eyes Open. He was thrilled – he had a little camera, and he was incredibly serious about the fact that he was going to be a photographer. I said, ‘I can’t wait to see the photographs you’re going to make.’ And I wrote that in the book to him. The next year at Paris Photo, I was signing Carnival Strippers Revisited. He came up with the same little camera and gave me a book that he had just made. His father said simply, ‘He couldn’t wait to come to show you his photographs!’ So maybe one kid at a time is enough in life.