A few months ago, I moved back to Montevideo, Uruguay, for an indefinite period. After eight years living abroad – somehow estranged from my own country – I returned to my parents’ house, or rather to the house that once belonged to my grandparents, who have now passed away, to sleep in the room where my father slept as a teenager. Suddenly, I was immersed in a world of objects, some old – tablecloths woven by my grandmother, sets of china, antique compasses – and others unmistakably modern, such as Wi-Fi repeaters, electric kettles, and smart televisions. These are objects that aren’t mine, and yet I live among them, weaving around them each morning just to make myself a cup of coffee.

Throughout my family’s history, there have been many photographers – some officially acknowledged within the family, like my grandfather, my father, and my uncle, and others I’ve uncovered myself, like my grandmother and my mother. In my family archive, the figure of the female photographer is mostly absent, while the figure of the married woman – obedient, sensitive, and virginal – remains constant and uninterrupted. Perhaps because of the multiplicity of cameras and perspectives to which my family was exposed, and the endless migratory exchanges between Spain and Uruguay, alongside the photographic and film archive there are countless letters, notes sent with reels, images that crossed the ocean to be seen in another season, by different eyes, in different surroundings. The archive is both vast and, in many ways, unknown.

The relationship between Spain and what is now Uruguayan territory is fundamentally marked by settlements. Massive immigration led to the establishment of Spanish communities in the country, which first imposed themselves through bloodshed and violence, wiping out all Indigenous communities. (It’s believed that the first Europeans arrived on the Uruguayan coast in 1516.) My great-grandfather emigrated from Valldemossa, in the Balearic Islands, to Montevideo, Uruguay, leaving behind his wife – my great-grandmother – and my grandmother in the village. For a long time, he slept behind the counter of a bar until he managed to save enough money to bring them over. The story of families leaving and returning is repeated and multiplied across other Uruguayan families, although not all Uruguayans are descended from ‘those who came off the boats’, as we were once led to believe.

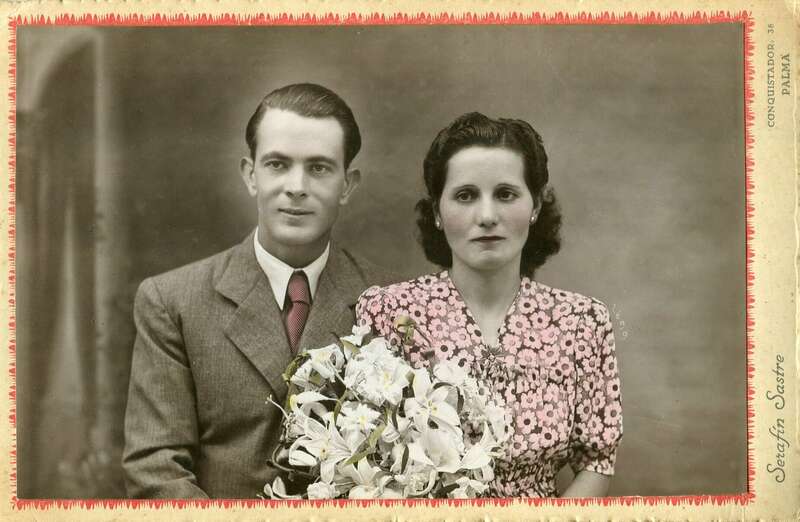

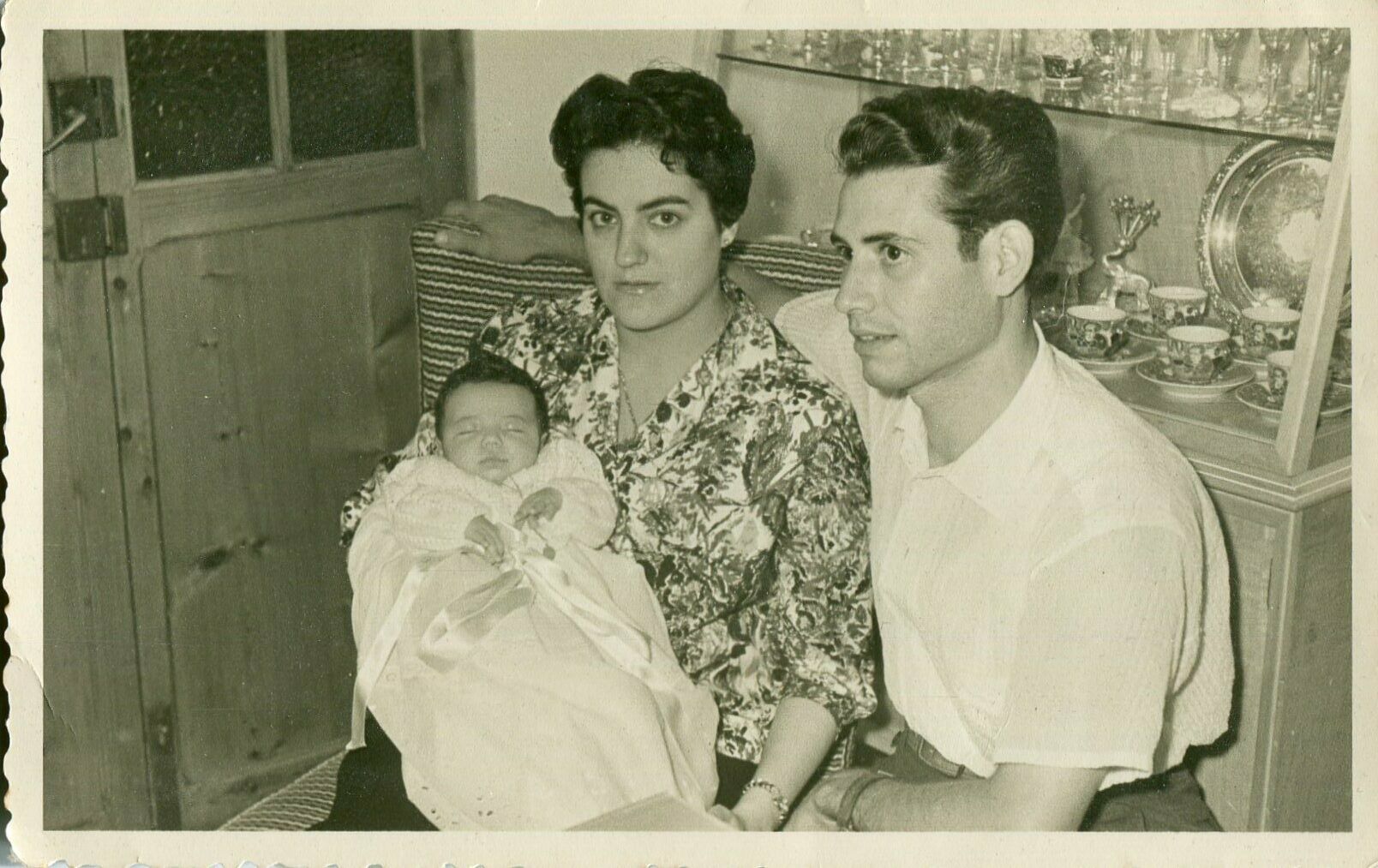

In this ongoing search for understanding, I began to encounter collections of wedding photographs. In the migratory correspondence my grandparents maintained with relatives in Mallorca, there were countless wedding albums, most of them belonging to the children of distant cousins, friends, or acquaintances. The photos were usually sent by the parents of those who married, as a way of institutionalising their child, positioning them as an adult inscribed within the canons of society. The images are mostly wedding portraits, or photographs taken before or after the ceremony. I can easily recognise those taken during the event: the couple posing at the entrance of a hall, the white dress brushing the floor, one partner holding the gown, the other standing upright and rigid, his suit almost choking his neck, both staring directly at the camera. Yet there are also others: images from the day before the wedding, or a photograph of a new mother cradling a newborn.

Far from happiness, fulfillment, or joy, what I feel first is tension and discomfort wrapped in hermetic structures.

Even as I know that the women who appear in the photographs are all different – different brides, different wives, different bodies – there’s a strange operation at play that makes them all seem similar to me, causing me to forget their distinctions and what sets them apart. As Judith Butler remarks, drawing on the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss,

the bride, the gift, the object of exchange constitutes ‘a sign and a value’ that opens a channel of exchange that not only serves the functional purpose of facilitating trade but performs the symbolic or ritualistic purpose of consolidating the internal bonds, the collective identity, of each clan differentiated through the act. In other words, the bride functions as a relational term between groups of men; she does not have an identity, and neither does she exchange one identity for another.Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge, 1990), 40–50.

In the context of 1940s and 1950s wedding photographs, this understanding – that the bride served, and still serves, as an object of exchange and as a sign of a family’s presentation or affirmation, and of its surname – is reinforced when I shift my gaze to the men in the images, who always appear upright, straight, and proud, their chests puffed out. Moreover, the way the couple is dressed contributes to this homogenisation. Women within these images were denied the position of desiring subjects, cast instead into roles of circulation and presentation.

As I search, leaf through, and linger over them, the wedding announcements once shared by letter take on a central place in this epistolary exchange. I choose three images. In the first, the woman looks directly at the camera, holding a baby in her arms. The man, meanwhile, looks away, his eyes lowered, likely focused on a relative. His posture is relaxed, yet his arm wraps around the woman, creating an almost circular shape with her, with their joined legs and the direction of their gazes. Their shoulders turn inward, and their arms form an enclosure, a fixed and stable pose.

A similar arrangement appears in the second and third images. In the second photo, the couple stands against a plain background, their bodies leaning toward each other. The man looks directly at the camera while the woman gazes off to the side. Their shoulders trace the line that defines the structure of the photograph. The third image follows a similar structure, but with a child added, standing between the adults. This time, all three look directly at the camera, their shared gaze forming the compositional axis of the image. The small child in the centre acts almost as a connective device between the couple.

The composition of these photographs traces a circular movement: it begins with a gaze, then shifts to the man’s body as he encircles the woman, and finally returns to the gaze, like a loop. But even as the women enact the social ritual and its associated norms and conventions, their bodies seem to suggest a disconnect. It’s through lingering observation and embodied imagination that I can pause and notice how the body says no, even if perhaps the subject – in this case, the bride – might have said yes. A displacement occurs from vocal to bodily gesture.

But within this structure of lines that seems closed, complete, and definitive, I became interested in searching for possible horizons – lines of possibility – perhaps inspired by the very approach Ariella Azoulay suggests in an interview, drawing on her book Potential History:

Potential history is an attempt to revise and reconfigure the key political terms in order to liberate history from its confinement to a past, which has been separated from the present. It is an attempt to narrate history as belonging, in a variety of ways, to a continuous present.Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, interview with Özge Ersoy, ‘Potential History,’ Jadaliyya, 28 January 2020, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/40300.

How can we reimagine ourselves by observing images, or imaginatively reconstruct those who came before us? There’s a potential repurposing, a constant state of flux.Elizabeth Edwards, ‘Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image’, Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (2012), 221–234. It’s to this that our generation of image-makers should return, in order to ask ourselves: what other performativities do women and non-binary people encounter today? How does photography enclose or categorise us nowadays? And what lines of possibility can we trace for those forms of reproduction that continue to be constructed?

It's within this subtle yet significant performative tension that I find an echo of Suely Rolnik’s Spheres of Insurrection: Notes on Decolonizing the Unconscious, where she describes how capital has shifted form over the centuries to end up its current stage:

It is life itself that capital appropriates; more precisely, its capacity for creation and transformation in the very emergence of its impulse – in other words, in its germinal essence – as well as the cooperation on which this capacity depends in order to unfold in its singularity. The vital force of creation and cooperation is thus channeled by the regime to build a world in accordance with its own designs.Suely Rolnik, Esferas de la insurrección: Apuntes para descolonizar el inconsciente (Tinta Limón, 2019), 41. For the English translation, see Spheres of Insurrection: Notes on Decolonizing the Unconscious, translated by Sergio Delgado Moya (Duke University Press, 2019).)

Rolnik then moves toward the concept framed in terms of insurgency, linking it to what she calls ‘the process of constructing the common’:

that one cooperates in micropolitical insurgency, whose agents come closer through the ‘path of intensive resonance’ that arises among frequencies of affects (vital emotions). This means weaving multiple networks of connection between subjectivities and groups that live through different situations, with singular experiences and languages, and whose common bond lies in the embryos of worlds that inhabit their bodies – imposing on them the urgency of creating forms through which such worlds can materialize, thereby completing their germination. This is only possible within a relational field where desires are guided by an ethical compass, which implies that the outcome of their actions will necessarily be multiple and singular.Rolnik, Esferas de la insurrección, 77.

I’m drawn to the idea of certain bodies coming into proximity through a resonance, and so I think of how the circle I perceive – this visual loop at first glance – can turn into resonant echoes that open up other spheres of the image. These echoes might engage the viewer into multiple forms and vibrations and allow us to imagine other possible resonant lines that displace the women from a passive role. Beyond recognising in these images the weight of a capitalist apparatus pressing on the brides’ bodies, the notion of resonance – cuerpo vibrátil – offers a way to imagine the relational lines that unfold between the photographs and the gaze that encounters them.

In line with Rolnik’s theoretical framework, Tina M. Campt, in her book Listening to Images, powerfully proposes an alternative, a practice, an exercise, ultimately a method of listening to photographs. She applies it, for instance, to a series of discarded cutouts of identity photographs produced in Gulu, central Uganda: faceless images in which only the bodies and clothing of the subjects remain. Campt reflects on how such faceless images might produce sound and concludes that they are not silent at all but reverberate with 'deafening intensity', their resonances pressing insistently upon the viewer.Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017), 18–19, reflecting on Martina Bacigalupo, Gulu Real Art Studio (The Walther Collection, 2013).

Something both similar and different happens in the images I’ve chosen. Two of them were taken in a photographic studio. In the first, I imagine the photographer’s voice giving directions, the rustle of the suitor’s clothing, or the buzz of the lights releasing their energy. Yet what resonates most vividly in my imagination is the sound of the woman’s breathing. Breathing is a soft sound, yet it can also be powerful, meaningful, charged with significance. The gaze, in turn, becomes another way of thinking about resonance and vibration. In two of the images, the women look directly into the camera: a gaze that confronts, pierces, and vibrates in registers far removed from subordination. By contrast, the upward gaze, looking beyond, resonates with desire and with horizons still to come.

When I first encountered these albums, I performed an almost unconscious gesture; only later, in revisiting the images I had chosen, did I begin to reflect on the way I arranged them. The act of gathering them together enacts a different – indeed, even opposing – operation from the one for which they were originally created: it establishes a relation among those women, a dialogue between those who were photographed and those of us who listen to them today. In doing so, a subtle yet sensitive historical and temporal rupture is inscribed, unsettling the ways in which these stories have been told.

---

This article forms part of Networking the Audience, a themed online publication guest-edited by Will Boase and Andrea Stultiens, developed in collaboration with MAPS (Master of Photography & Society) at KABK The Hague. The contributions emerge from an open call shared across the MAPS network, including alumni, and bring together artistic and critical perspectives on photography, publishing, and circulation. Together, the nine contributions reflect on how digital systems reshape authorship, readership, and meaning-making, foregrounding publishing itself as a creative and relational practice. Rather than addressing a fixed audience, the series explores how images and texts move through fluid, networked publics.