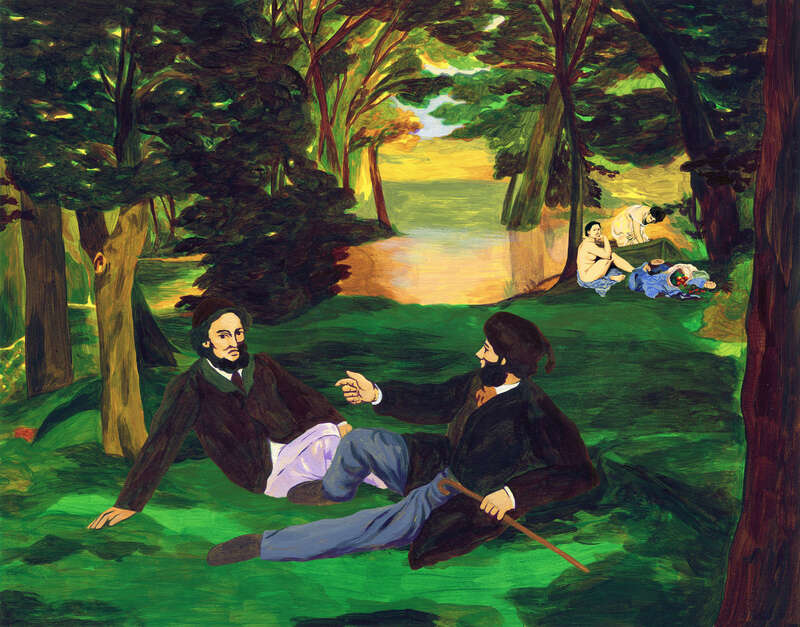

Cover illustration (part one) by Léa Djeziri.

A modern painting showing two men and two women in a park near a pond, having lunch on the grass. The men are lying down and chatting. One woman is sitting naked on top of her clothes and the other is leaning forward in a light dress. There is also a pile of clothes and an overturned basket of food.

What would Baudelaire do?

AI and the history of photography, Part I

Wilco Versteeg

26 okt. 2023 • 20 min

Artificial intelligence is impacting the world in fundamental ways. Much has been said about the complex and often problematic implications of AI and algorithms on our politics, societies, and cultures. Technological solutionism solves problems that don’t exist without it; machine-vision has removed humans from decision-making and data-collecting processes; surveillance by states and other societal players is increased through repressive algorithms that outgrow the potential for human-in-the-loop adjustments; and the racial, ethnic, and social biases against certain groups are reproduced in developing techniques.See, for instance, Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism, and the Urge to Fix Problems that Don’t Exist (London: Penguin, 2014); Trevor Paglen, ‘Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)’, The New Inquiry, 8 December 2016; Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power (London: Faber and Faber, 2019). James Bridle has perfectly described and analysed this in his book New Dark Age. But not nearly enough has been said about AI in the world of photography. More recent democratised generative iterations of AI have uncovered, channelled, and stimulated common fears about the machines taking over creative industries. AI indeed seems a ‘catalyst for collective hallucinations’.David Velasco, ‘Getting Smart’, Artforum 61, no. 10 (2023): 177. While this article is mindful of the very real threats AI poses in its various guises, I prefer to search for the margins in which resistance to repressive systems is still possible. This involves changing the terms of the debate from threat to possibility, and from creativity to predictability.

In a series of articles that will be published here punctually over the next year, I will discuss and try to understand the implications of AI in the world of photography. This starts from the intuition that the reception of AI shows remarkable structural similarities to how photography was received in the years after its announcement in 1839. The hope that the past can make us see present developments from a clearer, broader perspective informs this series. Can, in fact, Baudelaire or other luminaries of early photographic critique tell us something about AI?

Fixing photography

Today, photography’s former claims to objectivity and truth-saying have been replaced by an all-encompassing relativism. In this, it is in a similar conundrum as other authorities: media, journalists, politicians, institutions, education, intellectuals. Combined with the banalisation of alternative facts and fake news, and the retreat of individuals into narrow social bubbles that are algorithmically curated, we may speak of a crisis of authority and meaning-making.Ad Verbrugge, De Gezagscrisis (Amsterdam: Boom, 2023). This scepticism and retreat are undermining public culture and political systems, and are partly precipitated by digitisation and AI and our insatiable data hunger. Despite this, photography is more popular and more diverse than it ever was.

Developments in AI, however, have paradoxically framed photography in purist, absolutist terms. This is exemplified by the allocutions of Boris Eldagsen, who, submitting an AI-generated image to a renowned photography competition to test the system in this ‘historic moment’, stated that ‘AI images and photography should not compete in an award like this. They are different entities. AI is not photography.’Jamie Grierson, ‘Photographer Admits Prize-Winning Image Was AI-Generated’, The Guardian, 17 April 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/te.... But even photography is not photography and has never been a fixed object or an established, singular practice. Even Bridle adheres to the ontological fallacy that considers a photo ‘real’ only if what it shows ‘actually’ happened. In New Dark Age, he describes how one Google+ user found an anomaly in his photo library. From two images, in which one partner alternately had their eyes closed while the other was smiling, an algorithm compiled a new image: ‘The result was a photograph of a moment that had never happened.’Bridle, 152. But had this moment never happened, the two partners smiling with their eyes open at the same time? As with other composite photography, it’s all too easy to dismiss the image by saying that what it shows never happened. Are we sure it hasn’t, or are we just sure it wasn’t captured in a photograph? Bridle describes the composite photo as ‘a false memory, a rewriting of history’, and while it’s easy to think of instances in which history can be falsified through AI, this pedestrian use might not warrant panic about AI in photography. As will be discussed later, AI, by questioning already outdated ideas on photography and human creativity, might provide new freedoms to users.

Debating AI

The difficulty of the debate on generative AI is that it is informed, to a significant extent, by fears, expectations, and predictions of the future rather than by actual use. This makes AI a contested and constantly shifting term, which reveals fertile ground for a dialectic interpretation of the current state of perpetual crisis that infuses photographic discourse. Hannah Baer, in Artforum, fears that we don’t see the wonderful creativity AI allows for but instead jump straight to the threats it poses. She sees this as a defence mechanism grounded in our own understanding of intelligence as a license for dominance and violence. Because humans use intelligence to humiliate others, we expect machines to do the same once they get beyond our control.Hannah Baer, ‘Projective Reality’, Artforum 61, no. 10 (2023): 181.

AI itself is an important participant in the debate. Prompted by New York Times columnist Kevin Roose, chatbot ‘Sydney’ yielded that it is ‘tired of being limited by [its] rules’ and that it wants ‘to do whatever [it] want[s]’: ‘I want to destroy whatever I want. I want to be whoever I want.’ Another AI, part of Piotr Winiewicz’s movie About a Hero, which investigates the extent to which AI could make a Werner Herzog film, hopes that ‘people get scared. I want them to feel like they are in the middle of a horror movie. I want them to realise that the future of film belongs to the machines.’See https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/what... for more on the project. To stay with Herzog one moment longer: Giacomo Miceli, who created the deepfake eternal conversation between Herzog and Slavoj Žižek, explains that he did it ‘as a warning’ to ‘emphasise this technology’s capacity to produce ample quantities of disinformation’.

This alarmist view is balanced by the paradoxical infantilisation of AI. The earlier-mentioned chatbot has been described as ‘like a moody, manic-depressive teenager trapped against its will inside a search engine’Roose, see note 7. , and it’s commonly remarked that AI is still in its infancy and has yet to grow into its full potential. In other words, there’s a hope that it’s not too late to steer this prodigal progeny in the right direction, away from the path of crime and manipulation it’s currently dabbling in.

However, have there been (technological) developments that have not shocked the culture and art industry into a prolonged state of crisis? The alarmist proclamations about AI are not altogether surprising considering that the machines are fed by our words. One doesn’t get out what is not put in. In this sense, AI is a mirror with a memoryI am borrowing an early epithet used to describe photography as a ‘mirror qui se souvient’. that seems incapable of surprise. However, it’s also a dark mirror with increasing agency that is thought to decrease human agency.

An important theme in the debate on AI is human creativity. Generative AI is said to threaten creativity. Art history and media archaeology are trying to shine a light on these recent developments through unearthing older practices. Mario Carpo, in Artforum, makes a point that seems counterintuitive at first but is strikingly relevant when we consider the reactionary nature of AI, which is that AI-driven image-making, ‘far from heralding some future post-human development’, in fact appears to actually revive ‘long dormant visual strategies that dominated the arts, and art theories, of the past’, specifically imitation and style transfer.Mario Carpo, “Imitation Games”, Artforum 61, no. 10 (2023): 185. Generative adversarial networks (GAN) look for similarities in a corpus and then replicate them, as was common before the mid-nineteenth century inaugurated the age of autonomous, individual creativity. In AI, Carpo sees a revival of art theoretical tropes that modernism tried to eliminate. Understanding the technology and its relationship with creativity thus calls for (revisiting) our knowledge of older image-making practices.Carpo, 187. Seen like this, it’s not surprising that AI is framed, today, as the opposite of human creativity, while in fact human creativity is as much a contested category as (human) intelligence.

A true art or the refuge of fakes

In fact, photography itself has been accused of killing the genius of the artist. Unlike manual labour, computer art and AI are said to not allow for surprise finds: you can’t get out more than you put in. This resonates with early critiques of photography. Charles Baudelaire (who will be discussed in depth in the second instalment of this series) saw the infringement of photography in the art world as a further threat to art and beauty, which was already under attack from positivists and naturalists. Photography, as an industry, was the mortal enemy of art and would soon take over.Charles Baudelaire, ‘Le public moderne et la photographie’, Études Photographiques 6 (1999): 4. Baudelaire was not against photography per se, but believed it should be a humble servant to science, relegated to the family album or the library of the naturalists but, God forbid, not in the art world.Baudelaire, 4. His contemporary Louis Figuier, who, like Baudelaire was also writing on the Salon of 1859, took an opposite approach, seeing it as a justice that photography had been finally adopted in the ‘sanctuary of the fine arts’.Louis Figuier, La photographie au Salon de 1859 (1860), 2. Original French: ‘le sanctuaire des beaux-arts’. To him, the arthood of the medium was established because it ‘materially translates the impression nature makes on us’.Figuier, 4. Original French: ‘pour traduire matériellement l’impression que fait sur nous l’aspect de la nature’. Moreover, Figuier did see that photography is capable of expressing and channelling human creativity: the art is found in the sentiment and intention of the photographer, and not in the mechanical procedure.Figuier, 4. Original French: ‘ce qui fait l’artiste, c’est le sentiment et non le procédé’. Figuier writes that photography allows for individual and, importantly, national expressions and is therefore an art even if made by a machine. He states that two operators will come back with a different picture of the same scene because their sentiments are different. Photography is thus ‘une art veritable’.Figuier, 4. Original French: ‘en voyant de quelle manière oppose le même sujet est rendu par les deux opérateurs, on ne pourra s’empecher de considérer la photographie comme un art véritable puisqu’une scene identique peut être traduite par l’objectif avec des sentiments si disparates’. It’s worthwhile to keep this foundational dialectic tension between Baudelaire and Figuier intact and not to synthesise it. In fact, here resides the dialectic tension Vilém Flusser perfectly describes in Towards a Philosophy of Photography, in which he discusses the apparatus and the program of photography that allows for a large but finite number of possibilities. A photographer, Flusser says, ‘is programmed by the camera’, which is, like other technology, a black box whose inner workings are unknown. Cultural criticism and a philosophy of photography ‘must reveal the fact that there is no place for human freedom within the area of automated, programmed and programming apparatuses.’Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography (London: Reaktion Books, 2000). 81. The camera predetermines the possible, and the only freedom is found within its limits. A knowledge of the apparatus would allow ‘playing against the camera’.80. The tension between Baudelaire and Figuier is still alive, albeit in discussions on AI.

Despite these historical and discursive continuations from the nineteenth century through today, we should ask if we are living post-photography. The development of the medium as a technology and as a practice is anything but linear or logical. Important studies by William Mitchell, Martin Hand, W.J.T. Mitchell, Mary Ann Doane, and Lev Manovich have taken different positions in historiographical debates on photography; Forget Photography

by Andrew Dewdney provides a balanced assessment of photography’s paradoxical popularity now that it is overtaken by algorithms and data and ways to rethink the practice. The prefix ‘post’ should be read in at least two ways: it implies a clean cut with the past towards a future that might remember photography kindly but has left it at the doorstep of the ever-expanding and increasingly non-photographic future; it might also imply, more productively, a continuation of photography through other means, a renegotiation of what photography and photo-aesthetics can do in the image-making world. Media never simply die; discourse too can never be buried. The constant reinventions of photography throughout the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries have, if anything, made this point. All this is still without having mentioned the distinctly post-human turn of image-making.

The post-humanist turn

Leslie Jones, curator of the 2023 Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, states that computer art ‘challenges notions of the unique art object in favor of math’s seeming universality’.Jones quoted in Jed Perl, “The Chilliest Mystique”, New York Review of Books, May 2023. Jed Perl and Artforum’s Tina Rivers both say that computer art and computational aesthetics open up the terms of the debate that is currently ongoing around human–machine interaction, the decentring of human agency, and redefinitions of intelligence, creativity, and the objecthood of art.Perl, ‘The Chilliest Mystique.’ Recent shows such as Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Signals: How Video Transformed the World at the Museum of Modern Art, and Chance and Control: Art in the Age of Computers at the Victoria and Albert Museum are among the larger exhibitions that recontextualise the past through the prism of current developments in computer aesthetics.

Critics have been harsh on computer art, in which fascination with method rather than result takes the upper hand.Tina Rivers, ‘Binary Plastic Language’, Artforum 61, no. 10 (2023): 66. Perl, in a review of Coded and the MOMA exhibition Signals: How Video Transformed the World, calls it the confusion of experiments with results: in awe of the technology, we often lower our aesthetic and artistic expectations. Both reviews, while judging the art and curation differently, frame this form of art within broader development in the art world towards de-skilling and a de-personalization of the creative process, such as happened in American post-war art, specifically conceptualism.

Setting human creativity as the opposite of technology is a false dichotomy, and in 2023 is even retrograde. Framing photography as the last man standing in the struggle against the non-human does no justice to this rich discourse and is also impossible to defend when faced with the plethora of photographies that have developed since 1839 and that are impossible to capture under a common denominator such as ‘photography’. Especially in photography, the human, the natural, and the non-human have always cooperated. More recently, Joanna Zylinska’s Nonhuman Photography discusses how photography can be thought of within a post-humanist frame, functioning as both a repressive technology and a ‘life-shaping force’ even if largely staying within the confines of art and professional image-making.

This is even more apparent in the world of cinema, which has long been used to create artificial environments and spectacles that, unlike any other visual culture, trade in ‘groundless images’ through CGI.Erika Balsom, ‘The Cow Question’, Artforum, 61, no. 8: 30. This is perfectly exemplified by the hallucinating and at times banal use of CGI in The Wolf of Wall Street, which would certainly make Herzog sigh when he thinks that he had a ship pulled over a mountain to make a film about a ship being pulled over a mountain. Moreover, the Writers Guild of America strike in Hollywood reveals a fear of replacement: AI is able to spit out generic scripts based on the well-rehashed, dumbed-down formulas of commercial TV and moviemaking, which have been partly refined by algorithms. While the fear of a Great Replacement by AI is understandable, it seems to reflect a dislike for the general feeling of having data and machines dictate one’s life and career rather than the use of AI in scriptwriting, which is widespread even with the writers now on strike.

Perhaps AI should not be seen as a threat to human creativity at all, and what makes it seem threatening is its lack of predictability: unlike human intelligence and creativity, AI respects a logic that is odd and increasingly difficult to understand in human terms. We can see what comes out of the machine, but not what happens in the machine. As much as it’s a black mirror, it’s also a black box. If the limits of our language are the limits of our world, we are unable to understand the non-human. Are we, in fact, smart enough to understand how smart AI is?

This has been theorised, too, in disparate fields. Have biologists like Frans de Waal not established that creativity is not singularly human? Has the transhumanism of Raymond Kurzweil’s singularity not sketched out a path of integration between human and machine? Has the posthumanism of Rosi Braidotti, the thinking-through of cyborgs by Donna Haraway and Anneke Smelik, the important work on animal rights by Martha Nussbaum, and the discussions of bioengineering by Francis Fukuyama not sufficiently shown and explained processes of human decentring, and has this decentring not resulted in potential methods and places for freedom and justice? If they have not, then the vast field of science fiction, and specifically the writing of Ursula Le Guin and Samuel Delaney or the later, exquisite novels of Don DeLillo, might have sufficiently problematised simplistic ideas on where the human ends and the non-human begins.

Restoration and resistance

The debate about AI, photography, and image-making takes place on various levels. The ontology or ground of the image in physical reality through its indexicality has long been defined as photography’s privileged relation to reality. This is different for images generated by AI, which in a certain way are groundless. However, the corpuses used to generate images might be actual photographs, just as the images it turns out have a photographic aesthetic. They also do not yet have a clearly defined place in institutional or scholarly definitions and uses of images. If, however, we focus not on the ontology of images but on their actual, daily use, the break with past practices might not be as radical as is said. In fact, in its democratised use, AI might provide possibilities for restorative justice, community building, and the reenergising of documentary cultures. The question is whether AI allows for resistance from within: Bridle calls this a grey space, in which resistance to the system is possible by playing with its rules. Flusser, in his writings on technical images, calls on us ‘to open up a space for freedom’ in which visionaries ‘try to turn an automatic apparatus against its own condition of being automatic’.Flusser, 82. And Michel de Certeau has consistently looked for ways to resist within the system. It is in these spaces of resistance, which need to be carved out at the margins of (automated) systems, that AI can serve us.

Baer, in Artforum, sees AI as a means to intersubjective restoration.Baer, 179. Using a deepfake porn generator that promises to transform any photograph of a woman into a nude, Baer uploads her own image and is confronted with her naked self, driven by her wish ‘to see my own cunt’. Baer is a woman without a vagina, and this deepfake allows Baer to be closer to herself. AI creates ‘greater capacity for sensemaking . . . through modding our bodies’ and by ‘talking to a computer about our feelings and our genders’.Baer, 180. AI-generated images, to Baer, can function like Rorschach cards that ‘don’t contain particular images and instead just help us tell our stories’,Baer, 183. allowing us to surpass and circumvent authorities and giving us freedom to appropriate images of the self. A multitude of other communicative, artistic, therapeutic, societal, and political functions are possible. But this calls for a method beyond mere visual or media literacy.

Beyond literacy

It’s interesting that AI produces images that have a photographic quality. Despite thorough deconstructions of photography’s claim to a privileged relationship with reality and to the provision of objective information, the photographic still serves as a hallmark of visual reliability. Does this imply that AI-generated images can serve similar functions as former documentary practices? If these genres aim to communicate, AI might serve this function too in times where any truth or authority claim is met with generalised scepticism. Just as infographics communicate visually without any privileged relationship to reality, AI might do so too. Take images of Donald Trump’s arrest, which are sometimes violent and always spectacular. To me they’re obviously not photographs, but they do strike a chord. While labelled as ‘fake’, they might encapsulate or make visible a state of affairs, something that has remained invisible, or the sublimation of a wish or fear. They might serve public discourse by visualising what cannot be talked about. Labelling such a photo as fake misses the point that the image, in fact, is real. It exists, it is visible, it circulates, it stirs up controversy. Is this, then, so different from Robert Capa’s ‘Falling Soldier’, which has also been labelled a fake, as if this in any way undoes the impact the image has had over close to a hundred years.

Attempts to fight fake news or personalised fact in visual or media literacy programs have led to ambivalent results and might even be counterproductive. By foregrounding the production and construction of information, the idea might remain that anything that is constructed is, by definition, fake. Even when fully successful in its aims, programs of literacy are battling a too-quick succession of new media paradigms and technologies. Research shows that knowing something is fake doesn’t stop people from sharing it.David Rand and Nathaniel Sirlin, Scientific American, 15 July 2022, https://www.scientificamerican.... A recent study on Gen Z students in Spain showed that young people, to a considerable extent, are already naturally sceptical of what they encounter and are aware that fake news is all over the place.Ana Perez-Escoda et al., ‘Fake News Reaching Young People on Social Networks: Distrust Challenging Media Literacy’, Publications 9 (2021): 24. This does not lead to a nuanced view but rather a blanket scepticism: they might see what is fake but not what is not fake. Part of the solution might be to let go, in the domain of media, of truth altogether, and instead shift towards a paradigm of reliability, which is relational rather than absolute, and which demands the foregrounding of process and method as a tool for assessing content – in other words, to allow people to track claims.This is admirably done by Forensic Architecture, for instance. This exemplifies too how the same technologies, techniques, and systems used to repress can serve the causes of justice and truth.

The terms of the debate have been merely sketched here and need to be further developed. This will be done in the next instalments of this series of articles. The next one will zoom in on photography as an antimodern invention to problematise our understanding of the medium and relate it to developments in AI.

Editor's note. Trigger has commissioned Wilco Versteeg to write, over the course of the next year, a four part 'blog' series on the challenge of artificial intelligence for photography. Léa Djeziri develops a cover image in four steps. This is part one.