Installation photo, from the exhibition 'Eva Sajovic: Hanging by a Thread', 7 May -1 August 2021, Lapidarium, Gallery Bozidar Jakac. (© Jaka Babnik)

Weaving as ethical photography

Reflections of an artist in the age of ecological breakdown

I come from Slovenia, which in my childhood was part of the former Yugoslavia, a communist state.

Living in a country where the rule of supply and demand doesn’t apply meant that our needs were not dictated by desire but by function. Yet desire still existed – desire for a pair of Levi’s that I couldn’t have, for Uncle Ben’s rice and Barbie dolls, for all things I saw on TV when visiting relatives living in Italy (only a short drive away but the far side of “the iron curtain”).

The reality was that in our local shop we could buy trousers, rice, and dolls, but not the ones we wanted, the ones we truly desired. This made me resort to designing my own clothes by imagining the cut, choosing the fabric, and having them made by my granny’s cousin, who was a seamstress.

From an early age, I was taught by my grandmother to be resourceful, to find different uses for things that would now be commonly disposed of. It was a form of creativity that made life simple. The lack of choice became a kind of freedom.

In this essay, I talk about my transition from photography to weaving, not as the substitution of one medium of representation for another but as an evolution of my practice that fulfils my original intention as a photographer: to resist the prejudice, alienation, and passivity of the consumption-based economy. Rather than voyeuristic observation, complicit in the status quo, the loom represents for me artistic activism – beginning the process of repair and reconnection that must underpin the social and economic transformation required for our collective survival.

Eva Sajovic

14 apr. 2022 • 12 min

While photography is often conceived of as an artform that directly reflects reality or ‘the world as it is’, I suggest that that conception is fundamentally false. Susan Sontag begins On Photography with a reference to Plato’s Cave, where humans mistake the shadows cast on the cave wall for reality itself. Photography has become the artform parexcellence for the age of consumption and the delusion of infinite growth on a finite planet: reality and experience reduced to images in two dimensions, which may be easily and ‘cheaply’ replicated on a vast scale.

Turning away from the cave wall and back to reality in all its dimensions demands a rejection of photography – or at least a rejection of the idea of photography as offering a connection to reality and a counter to prejudice. It demands we reconnect with the natural limitations of and incorporate them into our practice, as part of the true meaning of photography

Although this redefinition of weaving as a form of ethical photography hinges primarily on purpose rather than process, I’ll also reflect on process – on the hidden and environmentally damaging impacts of photography, both analogue and digital, as well as the commonalities in process between weaving and photography.

S., Hidden presence project, Wales

Moral dilemmas

When I began as a photographer, my first subjects included women in prison, homeless people, Roma, Gypsy, and Traveller communities, and those displaced by ‘regeneration’ projects in London and elsewhere. My intention was to use photography as a counter to prejudice against ‘outsider’ communities – people who are marginalised, invisibilised, or demonised because they don’t conform to the dominant ideology wherein increasing material consumption (which depends on environmental destruction) is regarded as good.

I also used photography in a project called Picturing Climate, which documents the impacts of climate change on communities in Jordan, Cuba, and Bosnia.

My primary ethical concern as a photographer of people belonging to marginalised communities was the relationship between photographer and subject. In the words of Sontag, 'To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relationship to the world that feels like knowledge – and, therefore, like power.'Sontag, S. (2019) On Photography London: Penguin

Was I really doing anything to improve the lives of those I photographed? Who would see my photos? Most likely, my audience consisted of people who already shared my ethical perspective, people in my echo chamber. But if my photography was not actually serving to counter prejudice, what purpose was it serving?

Inspired by photographers before me who also seemed to feel this sense of inadequacy, I started looking for ways to create platforms for the subjects to represent themselves in a way that feels true to them.Wendy Ewald trained the subjects in photography, gave them cameras to document their lives and displayed the photographs in combination with their writings. Anthony Luvera assisted people to create their self portraits which were then used in combination with sound recordings taken at the time of photographing to deal with the objectivity of what is represented. My subjects became participants in the creation of the work. Partly to overcome the sense of voyeurism that I had, I also found myself drawn into political campaigning, for example around communities displaced by ‘regeneration’ projects. In the end, I found it exhausting, because I’m not a campaigner in that sense.

I began to reflect further on the impact of the processes I was using. The gelatine silver process is used to produce gelatine silver prints with black-and-white film and printing papers. A suspension of silver salts in gelatine is coated onto a support, most commonly film, fibre-based or resin-coated paper. The resulting photographic image gives visual expression to information. Gelatine used in analogue photography is a protein found in the bones of animals. Silver ions are toxic and get released into the water system through the washing of prints. When silver is extracted, it evaporates into the environment, with harmful effects to the liver, skin, and lungs.

In digital photography, light is recorded by means of an electronic sensor. Digital cameras consist of electronic components, some of which are produced using toxic substances. Precious metals are mined to create the cameras, lead is used for the microchips, and semiconductors are environmentally hazardous to produce. Mining for these finite minerals causes displacement of communities that live off the mined land and harms the environment. This is exacerbated by planned obsolescence, wherein digital cameras and other products are designed to go out of date within a set period to ensure new purchases.

It’s not only through the manufacture and use of materials – packaging materials, empty film canisters and used negatives, batteries and cameras, which often end up in the landfill – that the photographic medium creates waste and destruction. Vast amounts of energy from fossil fuels and nuclear power are also consumed when sharing, storing, and presenting images online, which in turn contributes to global warming. In 2019, the Shift Project, an energy transition think tank, published a report concerning the environmental impacts of digital technologies which concluded that “{t]he digital overconsumption trend is not sustainable in regard to its need for energy and raw material”.Lean ICT – Toward Digital Sobriety, The Shift Project, March 2019, https://theshiftproject.org/wp...

It began to seem to me that these concerns were not marginal or incidental. The medium of photography, which drives social media applications like Instagram, was the perfect complement to the false ideology of overconsumption and disconnection from and damage to the ecosystems on which life depends. Fulfilling my artistic intention of fostering the reconnection of people and nature in response to ecological crises required me to look beyond traditional photography.

I joined the Sustainable Darkroom photography project, a UK-based network of photographers experimenting with ‘cleaner’ photographic materials and darkroom practices, including developing film and printing photographs using plant matter instead of harsh chemicals.

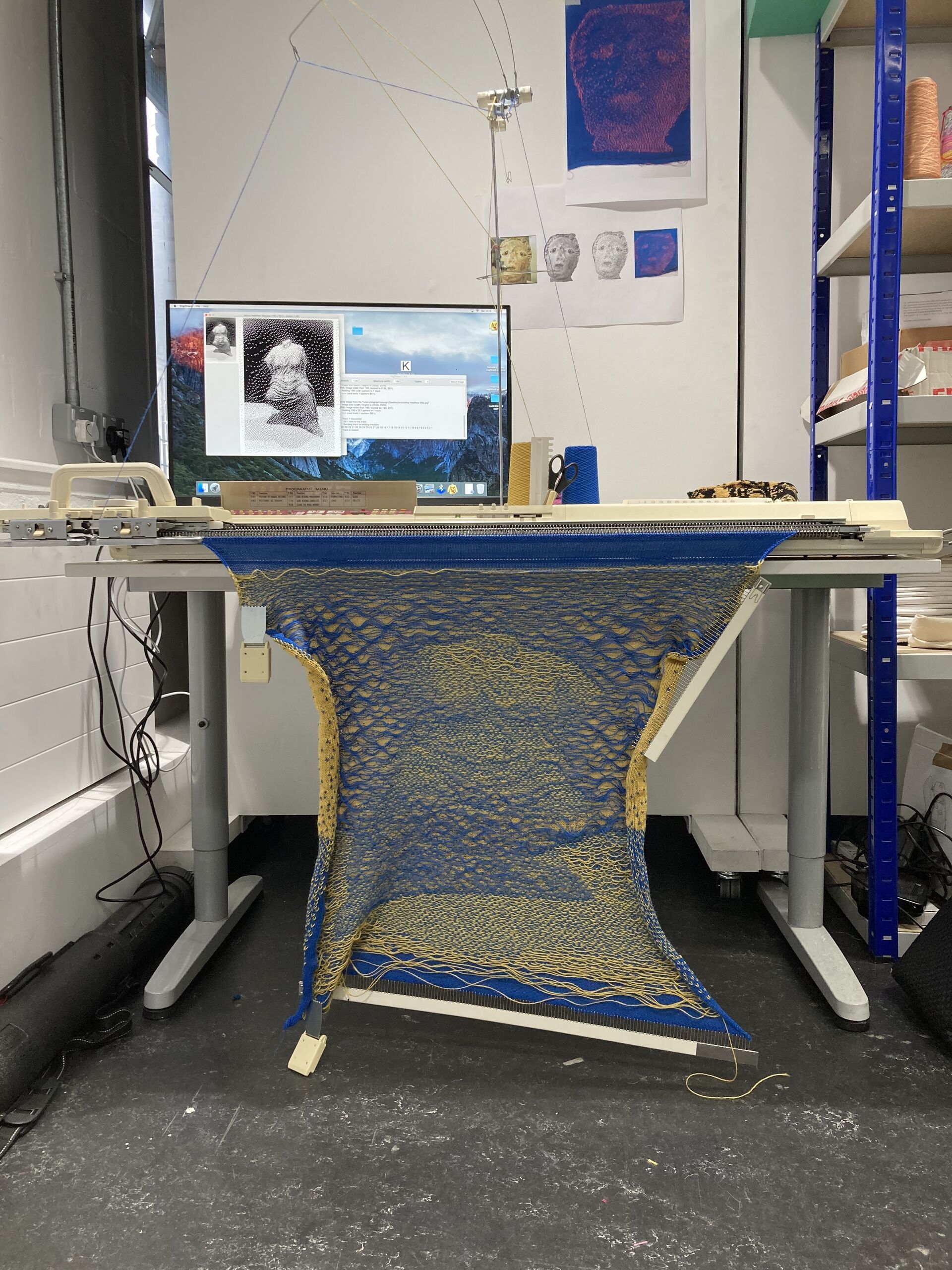

Installation photo, from the exhibition 'Eva Sajovic: Hanging by a Thread', 7 May -1 August 2021, Lapidarium, Gallery Bozidar Jakac. (© Kasia Wozniak)

Transition to weaving

Furthermore, to deal with my discomfort with the material and symbolic qualities of photography, I started to look for ways of practicing that would offer tactility, that would allow me to build on my photographic practice and at the same time champion the ‘cradle to cradle’ concept of making.

Removed from the process of touch, we get desensitised and alienated. It’s easier not to care if we don’t know what goes into the production of a consumable in terms of natural resources and human physical and emotional labour. The effect is exacerbated by the growth and ubiquity of the internet: life becomes super accelerated, which further contributes to disembodiment – not living in our bodies, not being grounded. There’s no time for critical reflection about what’s going on, where we are, and ultimately what matters and what’s at stake.

Anni Albers – one of the most important twenty-first-century abstract artists, a weaver who elevated weaving to the level of fine art, an educator, and an important writer on theories of art and craft – suggested that ‘we touch things to assure ourselves of reality’. She understood that by using our senses, we commit to grounding ourselves, becoming more present, more aware of how we, our bodies, impact the world around us. This awareness can be a tool for living a less wasteful life, living a life with more agency.

Tactility and skills that have been passed down from generation to generation enable us to be self-reliant. In a world of hyper-consumerism, we’re losing essential skills. Everything comes ready-made. To quote Albers again, ‘We have advanced as a society . . . but become insensitive in our perception by touch, the tactile sense. Our materials come to us already ready-made, we don’t need to knead the bread but only toast it. Little chance to handle materials, to test their consistency, density, lightness or smoothness. No need to make our tools, shape pots, fashion knives. Only unwrap the cellophane.’Albers, Anni. On Weaving (London: Studio Vista, 1974).

‘Cradle to cradle’ is a term coined by Walter R. Stahel, the Swiss architect devoted to sustainable strategies, in 1980, then further developed by the founder of Environmental Protection Encouragement Agency (EPEA), Michael Braungart, and the architect William McDonough in 2002. It’s a design concept wherein the end of a product’s use cycle is followed by the beginning of another cycle. The ideal is an infinite circulation of materials from birth – the ‘cradle’ of one generation – to the next and the next and the next, minimizing waste.Braungart, Michael and McDonough, William. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008).

I started experimenting with alternative photographic practices and materials like plant-based developers and salt-based fixer. At the same time, I took up weaving, reconnecting with the textile practices of my childhood. I explored weaving as a form of photography. For me, the two connect on multiple levels.

Weaving as ethical photography

As I began to weave, interesting commonalities with photography became apparent.

Weaving, like digital photography, is binary (consisting of ones and zeros) and a time-based medium. A woven piece, like an analogue photograph, consists of a surface that provides an aesthetic quality and a structure that gives it a functional quality.

The loom is a precursor to early computer technology. The first computer language was developed on a loom. The analytical engine developed by Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace in 1871, a precursor to the modern computer, was based on the loom. It used separate decks of punch cards, and by repeating them to execute a loop, made what we call a computer ‘programme’.

Weaving and photography both depend on light. Just as light is the essence of photography, the sun’s energy and photosynthesis initiate the process of growing the materials we need for weaving. Conceptually, the woven pieces are connected to my experience of photography – the materials that photographs are made of, what goes into their making and how their features correlate to the woven works I’m producing. Grain in photographs correlates to the stitches in weaving: the bigger the grain, the thicker the stitches; the finer the grain, the thinner the yarn.

Untitled 2

Colour photo paper is paper sealed between two layers of plastic. I work with plastic bags that I cut down to fine threads, which I then use to weave one layer of the pieces.

I’ve always been attracted to colour and did a lot of colour printing myself. This meant using a cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (CMYK) colour palette. By using CMY filters in the enlarger (K for black is created by adding CMY), a coloured print is achieved.

In my weaving, I use primary colours that correspond to cyan, magenta, and yellow. For yellow, I use pomegranate rinds; for magenta, avocado stones and madder root. These are by-products in the kitchen, give strong results, and don’t require any chemicals to bind to the fabric. For blue, I use indigo, which is a beautiful plant matter to work with as it produces many different shades of blue. It is made in a fermentation vat, which I keep alive by stirring regularly and feeding when its pH drops.

Like in photography, the format I use is always either rectangular or square.

I have also been experimenting with cyanotype by exposing an image onto the warp (vertical) threads and then weaving the weft (horizontal) threads into the piece to create cloth, expanding the image on the surface. This helped me to think about corrupted pixels, hacked imagery in which an intervention into the code of an image generates new, unexpected visual results.

I’m also bringing photographic imagery into my designs. My End of Empire series explores permanence and impermanence, and the rise and fall of civilisations, through a series of Instagram images of ancient splendours, restored to tactility and three-dimensional form with knitting.

Imagination, transformation, and the way forward

I began to realise my artistic intention of countering separation, in particular the separation of people from nature and of production from local communities. An economy based on colonialism and extractivism depends on wilful blindness to the harm it causes and a racism that permits whole regions of the world to be treated as sacrifice zones.

Weaving for me begins a process of reconnection, countering delusion and division and representing our fundamental connection to and dependence on natural processes.

Art is a process of self-transformation and a tool for understanding our own humanity. As woodworker and educator Peter Korn writes, ‘Through considering the work of my own hands, through the practical education of a life in craft, and through the shared experience of others – all seem to lead back to one fundamental truth: we practice contemporary craft as a process of self-transformation.’Korn, Peter. Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman (Boston: David R. Godine, 2013).

Transforming oneself is a step in transforming others, by leading by example.

Although it wasn’t my conscious intention, my transition to the medium of weaving also involved a reconnection to my own heritage and to myself, and it celebrated all the women who paved the way in making connections between art and technology – between coding, hacking, and weaving – and who thereby opened new ways of thinking about how to reclaim the binaries into something that’s not polarising.

However, our collective survival depends on a fundamental transformation of the way we live. That demands imagination and bold leaps of faith. Artists must play their part in reimagining and transforming our modes of representation. Reimagining photography as weaving is a step toward reimagining human society as functioning in a healthy relationship with the natural world.

Selected reading

Albers, Anni. On Weaving (London: Studio Vista, 1974).

Braungart, Michael and McDonough, William. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008).

Ewald, W. I Wanna Take Me A Picture (Boston : Center for Documentary Studies in association with Beacon Press, 2001)

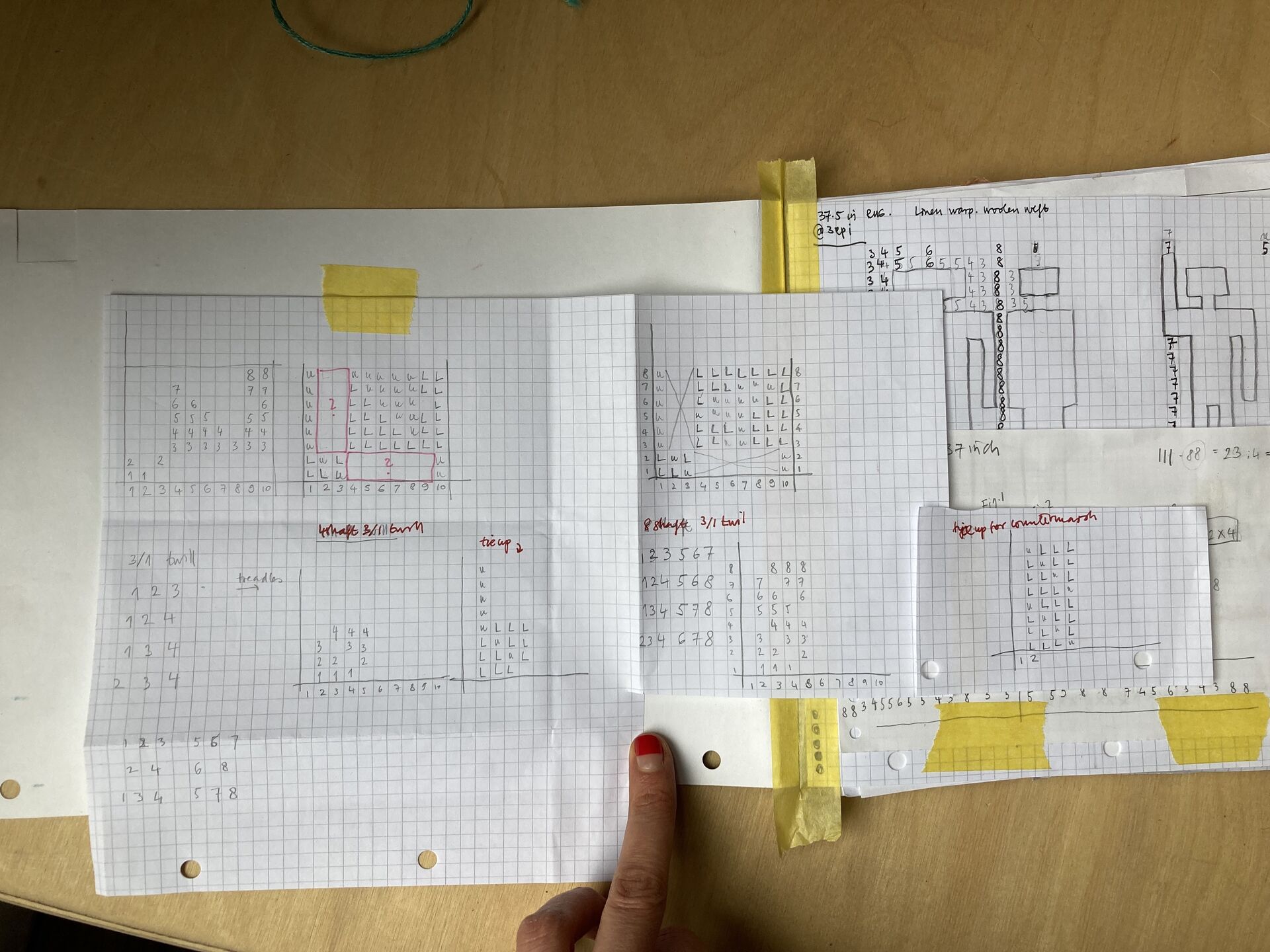

Jennerholm Hammar, Jakob. ‘Weaving Drafts at the Edge of the Abyss’. Accessed 23 December 2021. http://doc.gold.ac.uk/compartsblog/index.php/work/weaving-drafts-at-the-edge-of-the-abyss/

Korn, Peter. Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman (Boston: David R. Godine, 2013).

Lean ICT – Toward Digital Sobriety, The Shift Project, March 2019, https://theshiftproject.org/wp...

Luvera, A. Residency (Belfast, Northern Ireland : Belfast Exposed Community Photography Group, 2011)

Sontag, Susan. On Photography (London: Penguin, 2019).

Sustainable Darkroom, http://www.londonaltphoto.com/sustainable-darkroom-about.