Unimaginable publishing

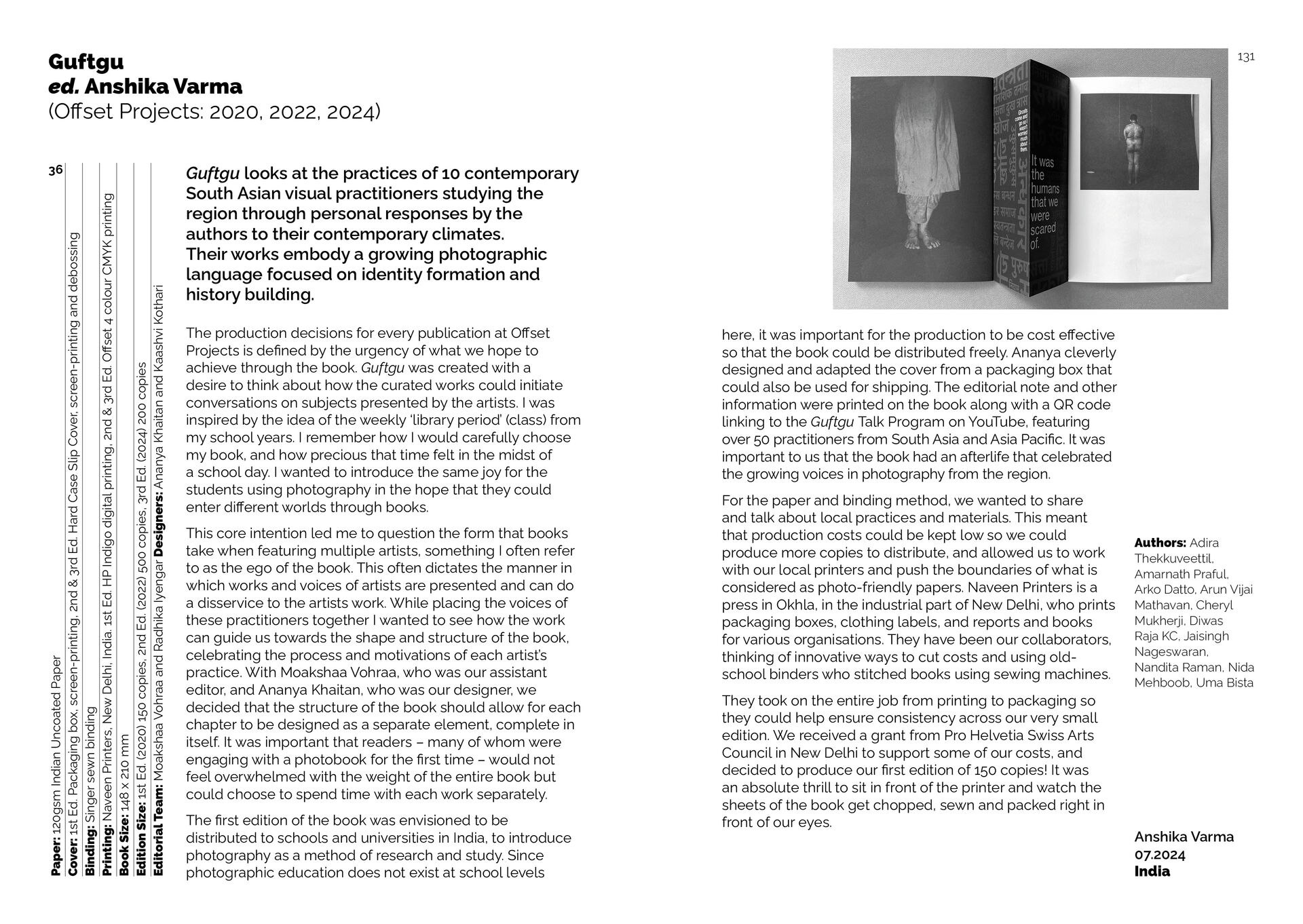

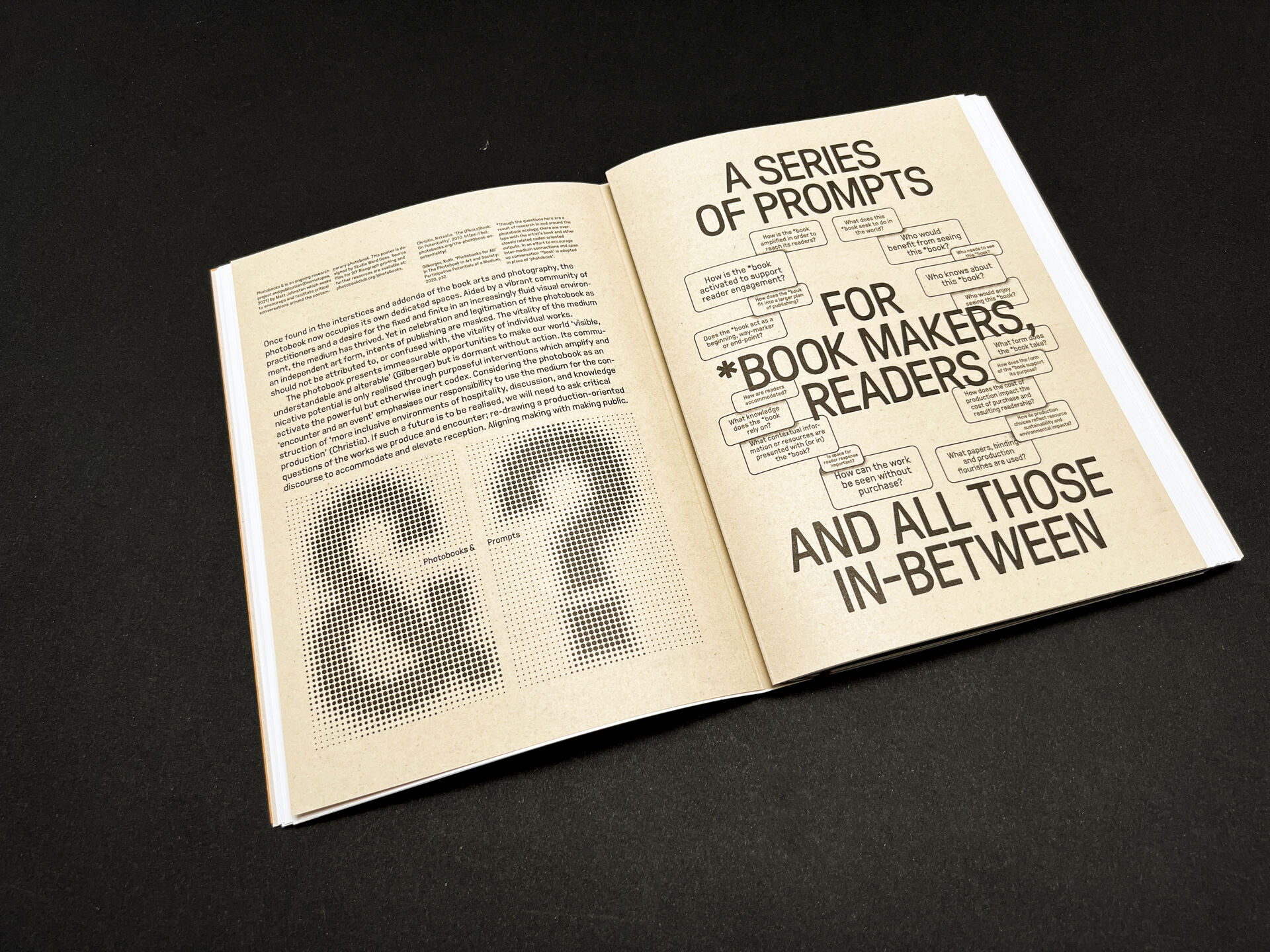

Editor's note. The Sustainable Photobook Publishing (SPP) network has just released What Makes a Photobook Sustainable? We asked Matt Johnston to explore ideas from the publication and challenge traditional photobook publishing practices. He argues that rethinking the industry's infrastructure can pave the way for more sustainable and accessible approaches, such as impermanent photobooks and distributed printing—ideas that, he suggests, demand a shift in mindset.

Matt Johnston

15 dec. 2024 • 12 min

Boring things

I picked up a copy of What Makes a Photobook Sustainable? from BOP Bristol, a two-day photobook festival to which I arrived early enough that many publisher tables were still vacant, featuring only a single sheet of A4 paper designating the surface to an exhibitor. In place of the spectacle and distraction of the photobook was a view of the systems and logistics required of such an event: trestle tables, chairs, extension cords, and Wi-Fi codes. As exhibitors filled the hall, their own systems meshed with those of the festival. Books were removed from ubiquitous clear plastic boxes and payment points were connected to the network. Focusing on the underlying structures of this festival brought my attention to the very real resource implications of photobook selling and prompted me to begin unfolding the numerous layers that comprise photobook ecology. Community, discourse, product, economics, infrastructure.Traditional use of the term ‘discourse’ would encompass ‘product’ also.

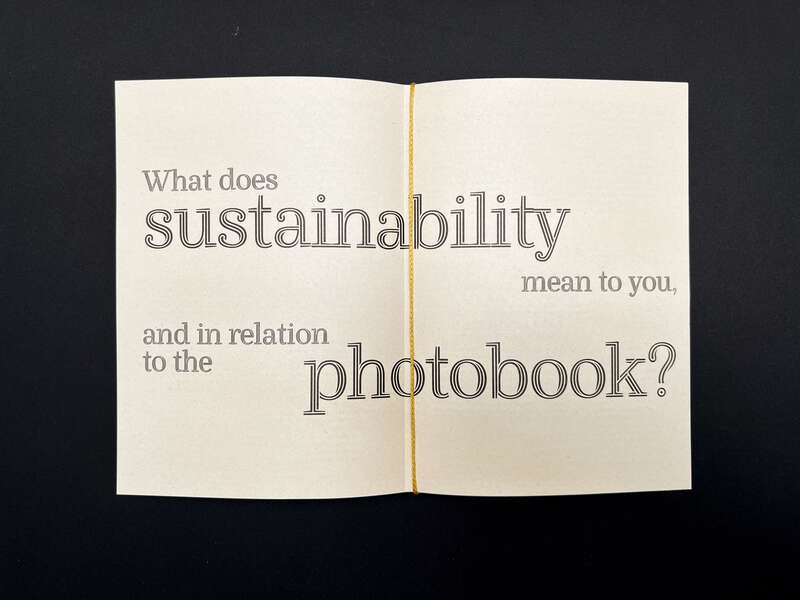

Local materials research for What Makes a Photobook Sustainable? at Yodomo textile reuse hub in East London, where we sourced the fabric binding cord.

It’s the last of these layers – infrastructure – that receives only marginal consideration in conversations on the photobook. This is hardly a surprise, given that a call to consider infrastructure may appear ‘a call to study boring things’,Susan Leigh Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’, The American Behavioural Scientist 43, no. 3 (December 1999): 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276.... but this is what WMAPS? invites. And it does so with an energetic honesty. Far from boring. WMAPS? moves beyond carefully narrativised accounts of the process of publishing common in contemporary discourse (a kind of contrived behind-the-scenes that privileges design and print) to inspect the significance of connected mechanisms that bring photographic works to their publics. This transition, from 'materials and processes' to the 'systems in which books are designed, made and circulated’,Tamsin Green, 7. echoes the organic development of the Sustainable Photobook Publishing (SPP) network and their 'three years of conversations’ from which WMAPS? Is constructed.Tamsin Green, 7. The result is pragmatic and imaginative. The book’s contributors ask and answer disarmingly ordinary and mundane questions about the seemingly ordinary and mundane, yet in tone and totality create a compelling call for infrastructural introspection.

Questioning the role and influence of infrastructure on what is published and how it is valued is not unique to the photobook. Jonathan Gray has suggested that the ‘established systems’ for managing scholarly work could be ‘so ingrained as to constitute a kind of “infrastructural a priori,” providing conditions for recognition, legibility, and relationality’.Jonathan Gray, ‘Infrastructural Experiments and the Politics of Open Access’, in Reassembling Scholarly Communications: Histories, Infrastructures, and Global Politics of Open Access, eds. Martin Paul Eve and Jonathan Gray (MIT Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpre.... The photobook, likewise – even with its avant-garde spirit – remains surprisingly traditional, infrastructurally speaking. Content, design, and form may vary wildly, but the processes through which the work is made, made public, encountered, and reviewed do not. Change under these conditions is not easy. Building a more sustainable and conscious medium in the confines of established conventions often necessitates palatable and small adjustments. Such seemingly minor modifications may add up to consequential changeIn the 2022 SPP roundtable, Tamsin Green spoke of the potential for ‘everyone doing a bit’ in a way that is ‘collectively better than a couple of people doing everything really perfectly’, which can be realised in this manner. This sentiment is complimented rather than supplanted by the more radical ideas in this essay, and supported not only by the SPP networks events but resource lists as well: https://www.manualeditions.com/resourcelist. but WMAPS?

also hints at ways we can directly confront, or else redraw, how it is conceivable to publish.

Risograph printing the UK edition of the book at the University of Westminster.

An infrastructural glitch

There are two particularly exciting ideas I’d like to pull from WMAPS? and the SPP network discourse: the impermanent photobook and distributed printing. Among the many thoughtful and creative ways to seek sustainability in publishing,Paper type, paper size, inks, offcuts, cargo bikes, and 3D printed display stands all feature in WMAPS?. the concepts of a photobook with a lifespan, and of a work with multiple printers, jarred somewhat. They were surprising. Hard to imagine. Thus, interesting. Take the question of permanence and its associations with the photobook, a medium enjoyed amidst a flow of digital content for its fixity and unchanging nature. Can a seemingly baked-in requirement of the photobook – that it stands against the flow of time – be reversed? I’m speaking here not of a genre of conceptual art in which decay or destruction is part of the work,Brought to the fore recently in Banksy’s Girl with Balloon/Love is in the Bin (2018) shredding at Sotheby’s. nor of the photobook-as-performance,At the 2023 Format Festival in Derby, England, Vassilis Triantis tore sections from his book printed on compostable paper, to be planted along with a seed by participants. but of a shift towards naturally unstable materials and outputs. Inks, papers, and bindings that over time break apart and break down. Ed Sykes asks whether it’s ‘kinder to the planet to make a product that lasts hundreds of years, or one that has a naturally shorter life cycle’p. 41 . The answer, of course, is complex and depends a considerable amount on what purpose the work is brought to life for. But the principle is sound.

It’s not hard to conceive of individual works dotted amongst hundreds of other publications produced each year, but to imagine them as commonplace requires a leap. The impact on infrastructural norms would be significant. Would archivists, librarians, and collectors employ ‘gentle tactics to maintain [artworks] in their current form’?The MoMA conservator’s approach to Dieter Roth's Wait, Later This Will be Nothing exhibition in 2013, in which maintenance was sought over preservation or decay reversal: Robin Cembalest, ‘Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Self-Destructing Chocolate Head’, ARTnews (blog), 21 February 2013. https://www.artnews.com/art-ne.... Would the bookshelf become a curious display of decay? Organised by date of expected demise? Would book prices decrease in line with expected shelf life or increase through market-driven fear of missing out?Would collectors even exist? What value system would need to be adopted if the photobook could no longer be considered an investment in art (at least in a traditional sense)? And the second-hand market – maybe this rewards skill in book maintenance as much as personal networks and available funds. There are other ways to look at the topic that emphasise what can be gained. Knowledge of the finite life of the image on the page, and the page itself, will necessitate more robust practices of digital archiving, new ways for people to engage and read without purchase or else without presence. Perhaps the second edition or open edition becomes more widely adopted – or, if nothing else, a preordained moment of consideration for new audiences, for contemporary relevances of the work at hand and for the possibilities of update and augmentation.

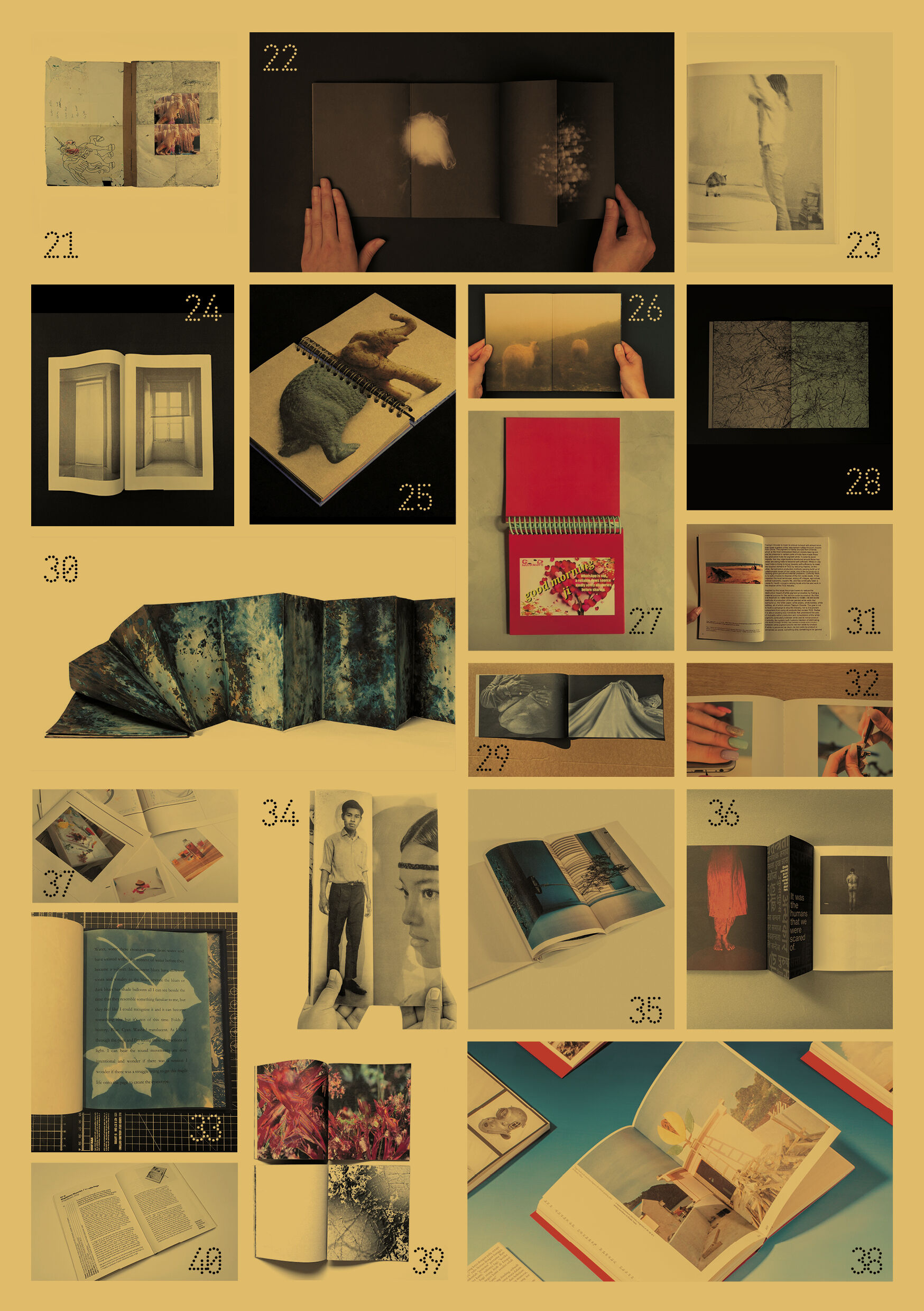

A move away from the photobook as unchanging object can be seen also in distributed printing, which sees work concretised in different locations using local expertise, techniques, and materials. In the case of WMAPS?, editor Tamsin Green plans to partner with other publishers to ‘print and circulate the book’ in other geographic regions.p. 140 It’s a strategy that enables the engagement of global readers through the haptic experience of the book whilst also reducing the considerable resources needed to transport books across continents. This is not the only benefit though, as distributed printing (or its more ambitious partner, distributed publishingA difference best summed up in the autonomy given to the printer or publisher: more control over content, design, and marketing, and even finances in the latter case. ) has the potential to construct new products, audiences, and conversations that are shaped by local and regional forces, not to mention their unique infrastructures. It’s not novel in the publishing industry, but photographic examples remain rare. In 2018, Antoine D’Agata’s body of work Oscurana was given to six publishersEdiciones FIFV, Inframundo, KWY, Le Dernier Cri, Sub Editora, and Void. to realise in their own ways. The collaboration, which also produced a special edition boxset, remains an outlier, in part because of the infrastructural headache it causes.

Established protocols in funding, publisher agreements, copyright, competition entry forms, library cataloguing, and reviewing are all barriers. This approach doesn’t seem to fit. Again, however, there is much to be gained if such systems were to be reevaluated. Inverting the processes that meet the needs of the photobook-as-art-object as it finds its way to readers could have a profound impact on the medium. Starting the publishing equation with audiences and readers before working back to the publication may not suit all purposes of making public, but it facilitates a more empathetic ecology. In this inversion, it’s not only possible to imagine the broader adoption of distributed printing and publishing but also to see the strategy as a practical choice. If my experience of arriving early at BOP and in reading WMAPS? allowed infrastructure to be seen as distinct and study-able, then these proposals perform the role of a glitch in an otherwise smooth-running system – a feeling of strangeness that reflects an absurdity of existing expectations and our difficulties in imagining alternatives.

Horizons of the publishable

What’s required in order that these more radical experimentations can move from the terrain of the trial to the landscape of the ordinary is to a large extent infrastructural. Systems would be needed to support rather than hinder diverse approaches to publishing. But it’s here that the temporary suspension of this layer in the photobook ecology becomes too heavy to uphold. In practice, it’s nothing without accompanying discourse, products, economics, and a community of practice that it ‘both shapes and is shaped by’.Star, 381. The ideas I’ve touched on here confront the conventions and ‘master narrative’ that is ‘encoded into infrastructure’Star, 384. as much as they are encoded into each additional layer.David O’Mara’s comment that ‘the photobook world’ has particular ideas about ‘how the photobook should look and be published’ (p. 95) concisely draws attention to the embedded nature of normalcy and expectation.

A framework through which this sentiment can be better understood can be found in Rachel Malik’s concept of the ‘horizons of the publishable’.Rachel Malik, ‘Horizons of the Publishable: Publishing in/as Literary Studies’, in ELH 75, no. 3 (2008): 707–35. Malik’s core assertion is that literary studies has overlooked the ‘set of processes and relations’ that ‘govern what it is thinkable to publish within a particular historical moment’ and thus what is read (not to mention how). The photobook, a ‘publishing category’ in Malik’s use of the term, has constructed, and is constructed by, its own horizon of the publishable. A set of expectations complete with ‘distinctive publishing practices’, ‘relations with particular institutions’, and ‘interpretive possibilities’. With regard to content, design, and production, the contemporary photobook’s horizon is fairly broad. A Mark Steinmetz black-and-white hardback sits comfortably in photobook spaces alongside Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s spiral-bound scrapbook I carry her photo with me. Yet the thinkable ways in which to publish, the infrastructure through which to reach readers, is narrow.

This is not a universal situation.As Daria Tuminas makes clear, the ‘idea of transportation is central to Western dynamics of photobook circulation’ (p. 155). So too is the adoption of traditional publishing systems and a commitment to dedicated photobook processes. As recent publications have helped elucidate, practices of making public in the Global South are often necessarily agile and adaptable.See Wen-Hsuan Chang, Xsport on Paper: Samplings of Publishing Practices from the Global South, trans. Lim Kyung yong (Mediabus, 2023) and Fotobook DUMMIES Day, Tropical Reading: Photobook and Self-Publishing (Limestone Books, 2024), as well as Lim Kyung yong and Helen Jungyeon Ku, eds., Publishing as Method: Ways of Working Together in Asia (Mediabus 2023). Away from ‘the more established systems of Europe or North America’, publications must ‘extend their roots from under hard shells’ and sprout ‘from the cracks of concrete walls’.Liu Chao-tze, ‘Sprouting through the Cracks: Self-Publishing Attempts’, in Tropical Reading: Photobook and Self-Publishing, by Fotobook DUMMIES Day, 10–26, Limestone Books edition (Limestone Books, 2024), 25. Within those more established environments, however, the photobook-as-art narrative and a desire for works to be ‘made without compromise’ necessitates the use of infrastructure built around the authored object.Designer Hans Gremmen quoted in José Bértolo and David Campany, ‘A Questionnaire on the Photobook: Publishers’, Compendium: Journal of Comparative Studies, no. 2 (31 December 2022): 151–90. https://doi.org/10.51427/com.j....

Piggybacking on alternative infrastructures or engaging with existing (non-medium-specific) communities and conversations threatens the purity of the medium. To adapt, and to adopt alternative infrastructural horizons, requires some detachment. This is illustrated well in Tamsin Green and Eugenie Shinkle’s acknowledgment of the challenge that distributed printing presents to makers for whom an ‘integral part of the bookmaking process’ is being ‘on-press’.p. 79 They counter concern over loss of creative control by highlighting the gains: a ‘chance to develop new kinds of working models, and new relationships’,p. 79 but this is a difficult argument to make. Few layers of the photobook ecology encourage this side of making public. Few reward the generositySomething Martin Bollati refers to when discussing the possibility of print-at-home photobooks (p. 80). and humility needed to construct more ‘collective and less ego driven’ publishing practices based in ‘trust and sharing’.Eugenie Shinkle, 168.

Beginning with infrastructure to spark change in this atmosphere is one path; equally valid would be to look to discourse or economics. Wherever shifts begin to appear, forming new practices and relationships is vital in confronting the sustainability of the photobook and its concurrent issues of esotericism and accessibility.This is not to diminish or exonerate the resource-intense activity that is photobook publishing, nor to obfuscate it via a set of bundled concerns. Instead, it is to recognise that these problems are not independent of one another and thus may not require entirely separate interventions. To this end, WMAPS? forges a thoughtful path through the narrative of the photobook. It respects the elevation of the medium to art and the ‘joy of creating’Tamsin Green and Eugenie Shinkle, 81. whilst establishing a responsibility for revision. WMAPS? can be taken as a series of accessible interventions that support a little-by-many approach to future publishing practices, operating within an existing (and thus imaginable) horizon. Most exciting, though, are those more invasive strategies and subversive sentiments that could take root to form new and as-yet unimaginable futures for the medium.