Uncanny politics and its imaginations

How AI visuals can breed racism and help the radical right

Editor's Introduction

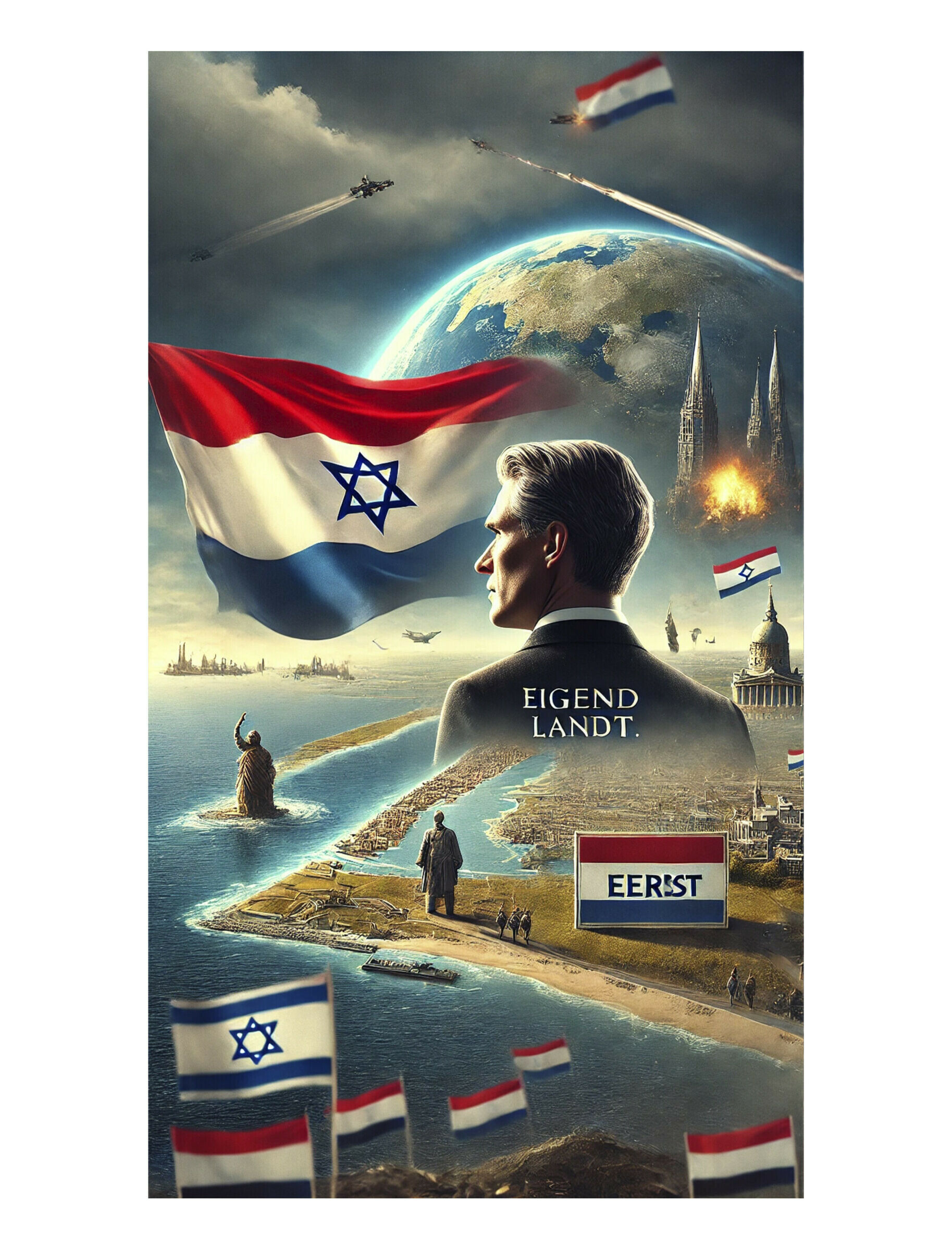

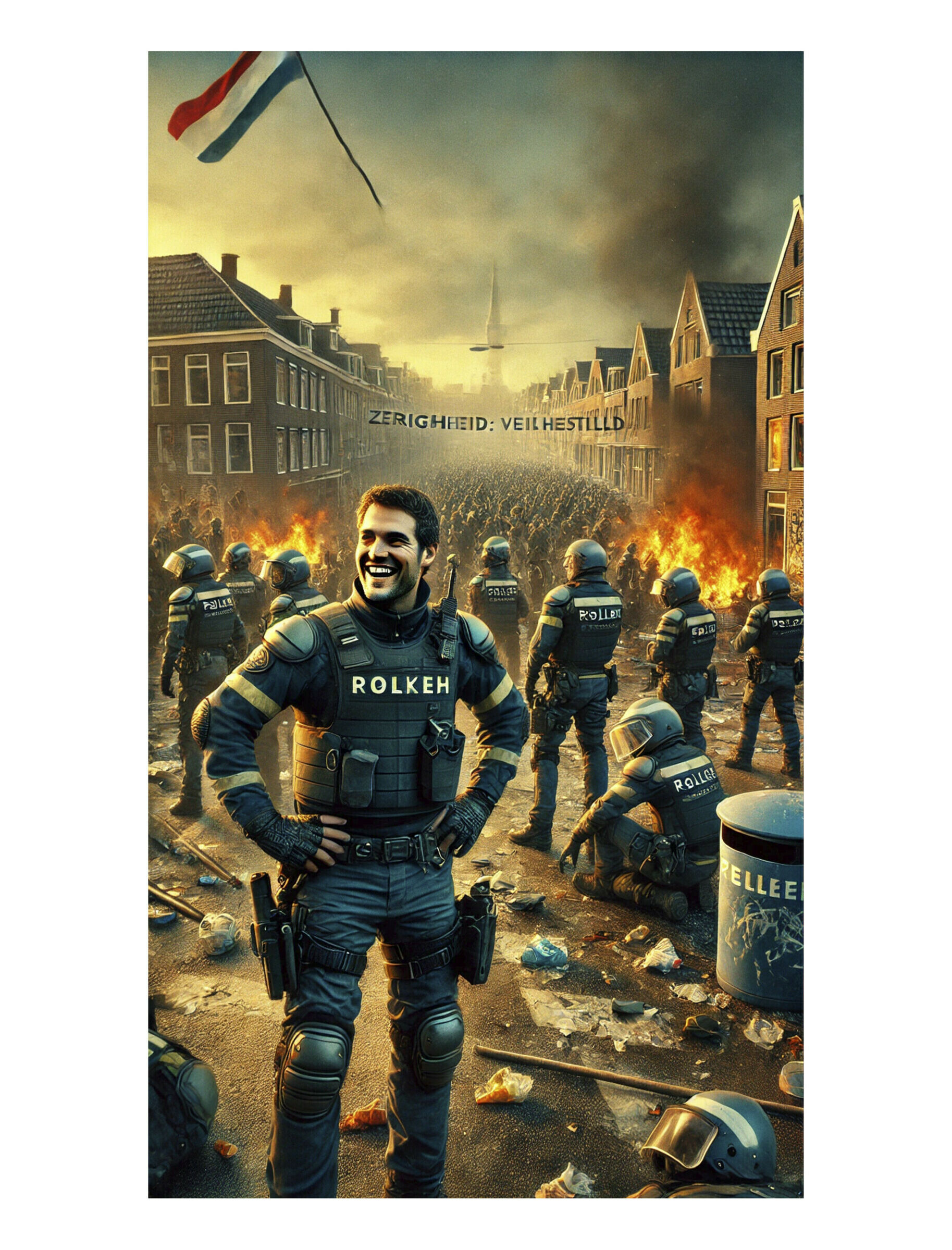

Alongside this essay, Fenna Jensma developed five visual experiments that explore how generative AI can translate political ideology into imagery. Drawing on the 2023 manifesto of the Dutch far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) and on images shared by its leader, Geert Wilders, she used AI tools to reveal how seemingly innocent aesthetics — sunlit landscapes, smiling families, familiar national settings — can carry exclusionary, nationalist messages. These experiments are not illustrations; they are critical, analytical extensions of the essay, showing how AI can make ideological ideas visible and emotionally persuasive.

Fenna Jensma

19 feb. 2026 • 17 min

I’m looking at an image of a landscape. In the middle of the frame is a young woman, the main character of the scene. She fills the frame from her breasts to her crown. The woman is white, her hair is blonde, she’s blue eyed and has a pointed nose. Except for a few laugh lines around her eyes and mouth, her skin is smooth and wrinkle-free. She stares at me with a radiant smile and gleaming white teeth. The whiteness of her teeth is reminiscent of a dentist advertisement. Her blonde hair falls over her shoulders. In the upper left, a bright sun is shining, causing some of her hair to appear white. She wears a white tank top, and I see the beginning of her cleavage, which is cut off by the bottom of the frame.

The woman stands in a landscape filled with tall grass bending to a gentle breeze. In the distance, the grass transitions to a patch of barren land. Above it, the horizon is lined with a row of trees. The woman’s silhouette divides the image in two. On the left, tree trunks fill the space on the horizon. The rays of the setting sun obscure the detail needed to determine what kind of trees they are. On the woman’s right, the trees are in clear view: they appear to be neatly lined poplars.

Other people stand in the tall grass behind the woman. In the lower left of the frame, a young boy with almost-golden blond hair dressed in jeans, a white T-shirt, and a blue checked button-down runs towards something that is happening behind the woman in the foreground. A hand is missing on his left arm. Behind the boy stands an adult man, seemingly the same age as the woman. He too wears jeans, a white T-shirt, and a blue checked shirt. He has facial hair and shoulder-length blond hair that flows in the wind. The sunlight renders some sections of his hair white. Like the woman, he has a radiant smile that reveals white teeth. In his right arm he holds a baby with blond hair. The baby wears a white T-shirt, and either short denim overalls or a skirt. Their tiny legs and feet dangle in the air. The man’s left hand holds someone else’s, though strangely, the hand seems to have more than five fingers. The hand belongs to another blonde woman, whose hair, slightly longer than the first woman’s, blows in the wind. She too wears jeans and a white T-shirt, with a green cardigan over it. She appears to be pregnant; I see a small bump between her hips and chest. The baby, the boy, the man, and the pregnant woman all look at whatever the boy is running toward. They appear to be extremely happy. On the right side of the image, I see a girl with long, dark blonde hair. She wears a long-sleeved shirt with red and white horizontal stripes, under denim overalls. Her eyes are downcast and her left hand is held by another adult man who looks at the girl and smiles. He wears a grey, low-neck T-shirt and blue jeans. His hair is brown.

Just above the cleavage of the main character I see a logo: white lines form a rectangle, with three white letters inside: PVV.

On 2 June 2024, the image I just described was launched into the world by Geert Wilders, initiator, leader, and only member of extreme right-wing Dutch political party PVV (Party for Freedom), via his X account. The caption read, ‘The sun will shine again in the Netherlands’. Three days later, one day before the European elections, he posted a similar image. This time the caption read,

Let our families feel safe again in the Netherlands, with the strictest asylum policy ever.

Make the PVV the largest on Thursday!

So that the sun will shine again. Geert Wilders (@geertwilderspvv), ‘onze gezinnen weer veilig in Nederland. Met het strengste asielbeleid ooit. Maak de PVV de grootste donderdag!. Zodat de zon weer gaat schijnen. #stemPVV’, X, 5 June 2024. Translation by X.

After the elections and throughout the rest of 2024, three more images were shared. The captions had a recurring theme, reclaiming the Netherlands, literally (‘Netherlands is ours! (hearts)’) or more poetically (‘the sun will shine again in the Netherlands’). Each image showed a different scene, but all portrayed heteronormative, traditional, white, fair-haired families, often in Dutch-looking neighbourhoods, flat countryside landscapes, or a combination of the two. The inhabitants of these scenes are white and always youthful. Women have long blonde hair, men blonde or brown. There are children of various ages. These people are blue- or brown-eyed and wear simple but bright clothing; black and dark colours are absent. Everyone smiles.

These images were AI-generated. They lack true photographic quality which would connect the scene to an event, staged or not, captured with the use of a camera. There are missing limbs, merging fingers, asymmetrical faces, and some violations of physics, such as weird perspectives or lightning situations that don’t match with reality. These images, unsurprisingly since most AI models are trained on datasets of images taken from this world, have similarities with stock and advertisement imagery.Caroline Mimbs Nyce, ‘AI Has a Hotness Problem’, The Atlantic, 2 November 2023. The images are, in short, imaginations.

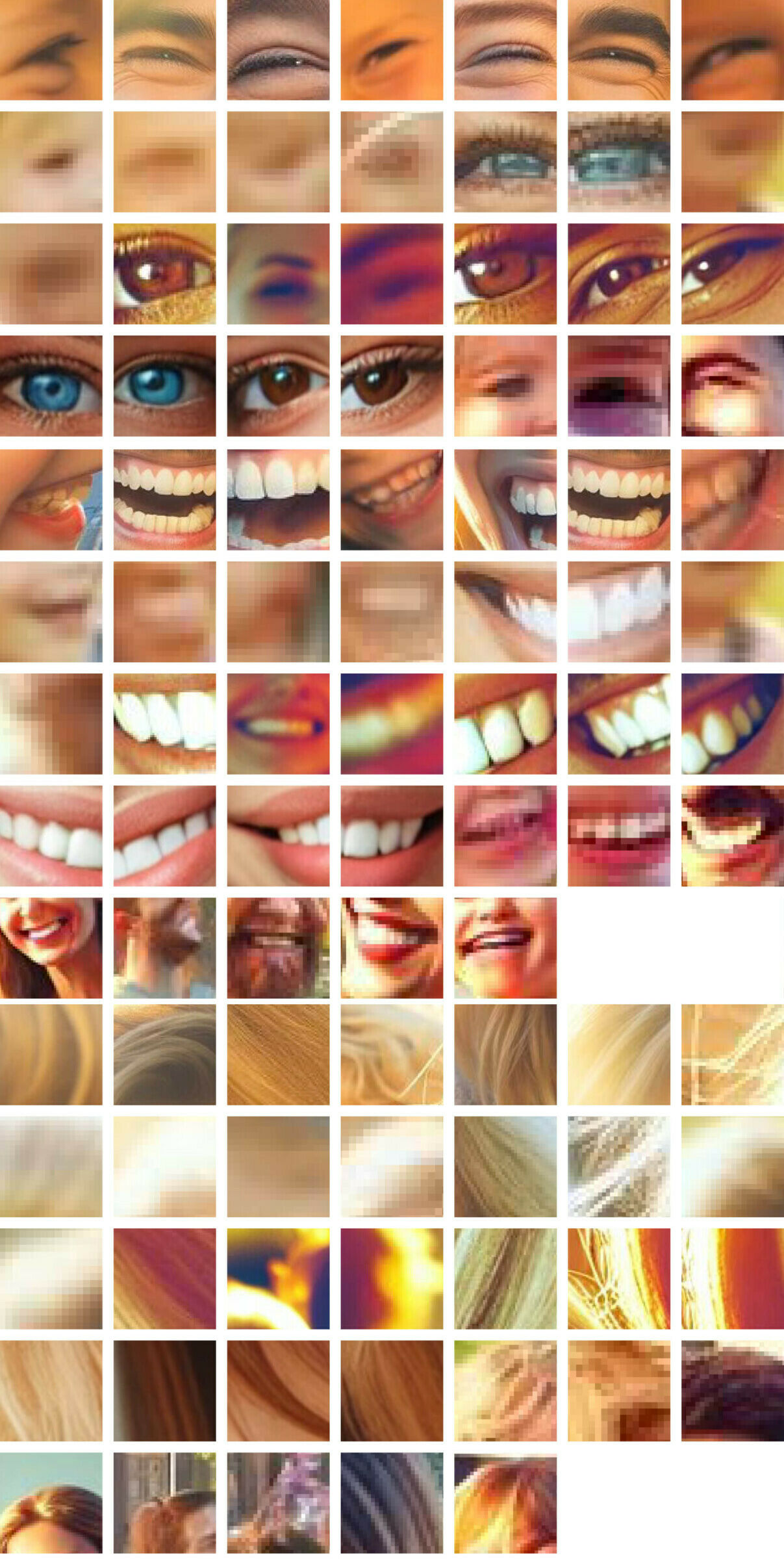

Experiment 2: Through reversed machines I tried to find out what prompts were used when the images, that Wilders shared, were generated. I received suggested prompts. Through this experiment I realized I would not find the original prompts, this data was not present in the images. I chose words from different suggested prompts, words that for me came the most close to the real intention of the AI generated images. Together I combined them with cropped versions of the AI images, my intention was to create an uncanney feeling.

In my work as a photographer, questions about imagination are part of the routine: How do I visualise certain subjects? How do I ensure that an image communicates effectively? What is the desired effect? When I worked as a photo editor in newsrooms, my job involved deciding not only how to illustrate certain news pieces, but also – and arguably most importantly – which images should not be used. I say most importantly because when selecting an image to accompany an article, I was not only looking for something that drew the reader in but also making a choice that contributed to the visual imprint the reader would carry with them whenever they thought about the topic at hand. Research has shown that in news coverage of soccer, for instance, matches of men’s teams are usually illustrated with action shots, whereas coverage of women’s matches tends to feature more ‘passive’ images zoomed in on facial expressions or moments just before or after a goal.Stichting WOMEN Inc., ‘Scoren Zonder Stereotypen: Onderzoek Naar de Mediaberichtgeving over Het Nederlandse Mannen- En Vrouwenvoetbal,’ WOMEN Inc., 2023, 14. This reinforces the idea that women’s soccer play is less dynamic than men’s. Similarly, images of Muslim women published in the media often depict them from a distance and almost always in such a way as to make them unrecognizable. As a result, they are portrayed as unreachable and anonymous, which further contributes to the ‘othering’ of Muslim women.Cigdem Yuksel and Ewoud Butter, ‘Moslima – Een Onderzoek Naar de Representatie van Moslima’s in de Beeldbank van Het ANP’, October 2020, 15. It’s therefore crucial to be aware of and to avoid repeating such stereotypical representations.

This insight led to my interest in the use of imagery by political parties. How do politicians make use of this power? Almost every Dutch political party uses photography in their party programs to illustrate different chapters. Each chapter deals with the plans that have been specifically devised for a particular topic, such as migration, housing, or social security. Usually, this type of imagery finds its origin in the realm of stock photography. Finance chapters are, for instance, almost always illustrated with a picture of money. The use of imagery by political parties, however, extends beyond their programs, arguably most notably to social media.

The combination of the images and the captions shared by Wilders clearly relate to his ideal society and what it should look like. Once shared on X, ‘real’ society takes hold of it. Users of the platform respond in a variety of ways. What’s striking is that there’s a strong urge to immediately point out what’s wrong with the image. Some commenters make fun of Wilders, responding with humour and pointing out all the glitches that AI included in the image. Perhaps this stems from a desire to warn others not to trust it. Similarly, the comments in which people respond with shock, referring to similarities with German propaganda in the 1930s, primarily appear to be warnings. But the desire to respond with an alternative image that uses the very same visual language is also noteworthy. Some commenters respond with their own AI-generated versions of an ‘ideal family’, characterised by the presence of racial, gender and diversity. This raises the question: to what extent does the production of reality begin with the production of images? Finally, there are also people who respond with (other) AI-generated images of racist, discriminatory, and dehumanising scenes.

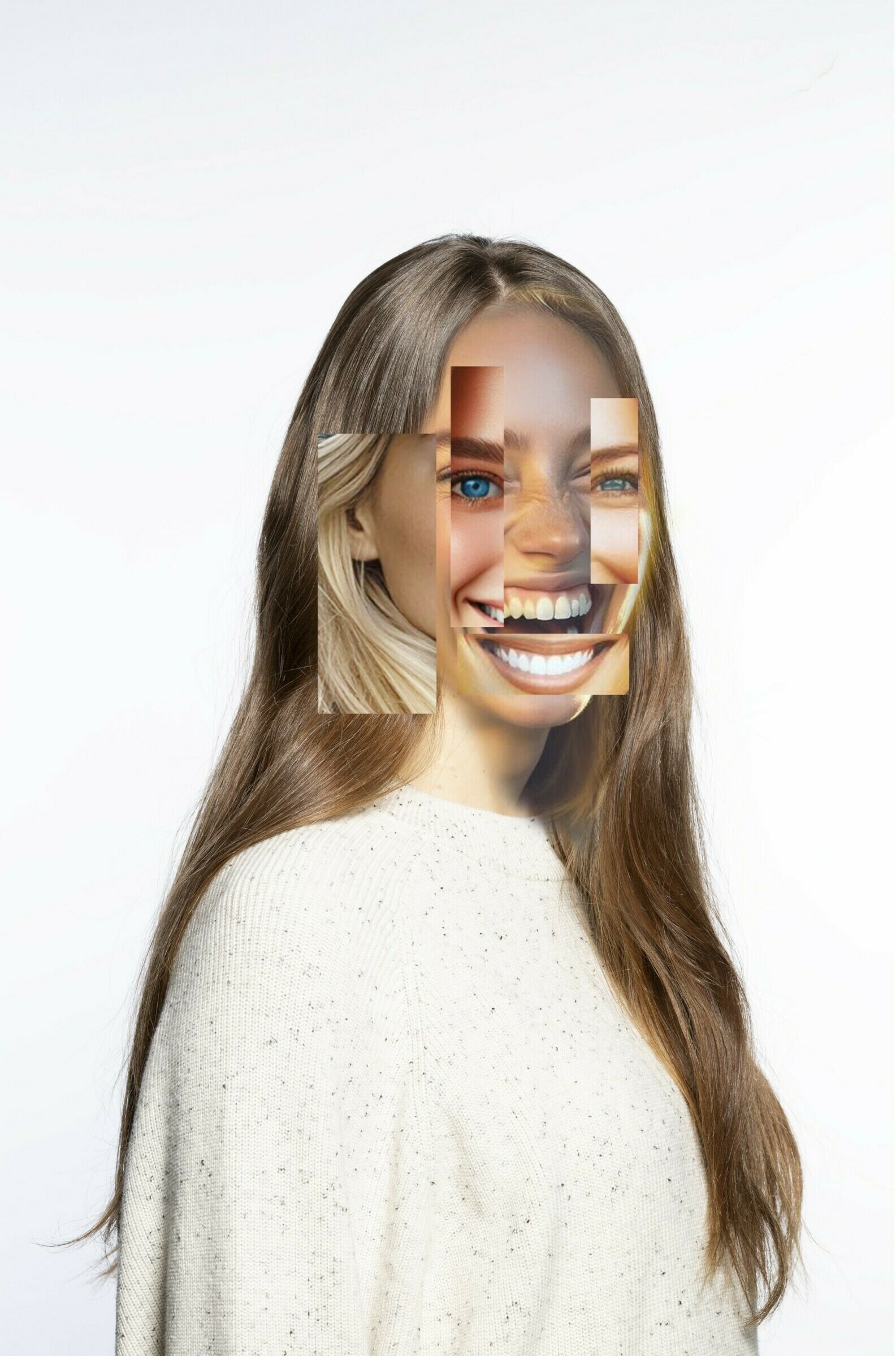

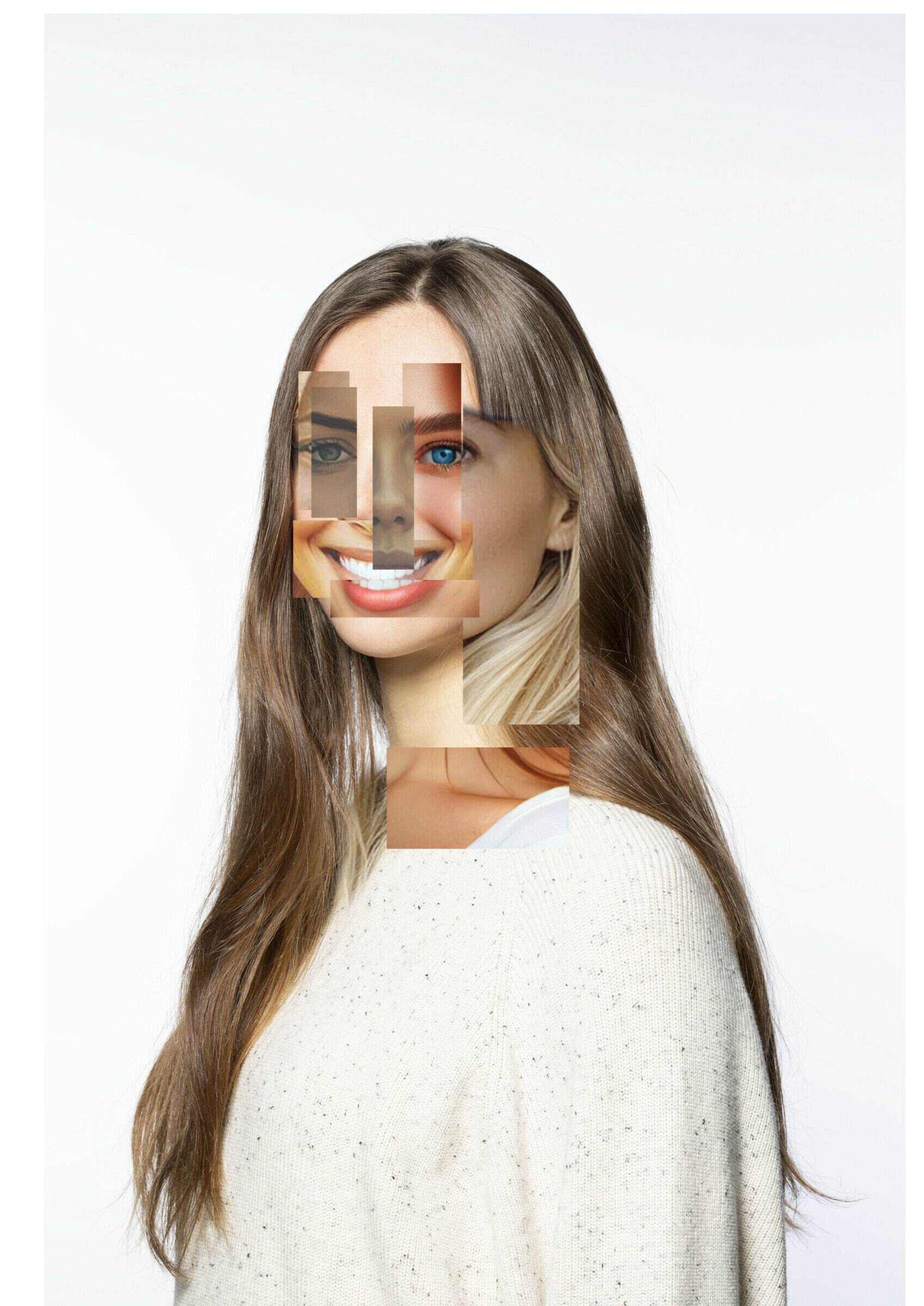

Experiment 4: January 2026, index of eyes, mouth and hair of the AI generated images of blond families shared over the past 2 years by Wilders

The images of ideal families posted by Wilders might be overlooked because the language accompanying them is noticeably calmer than the tone he uses elsewhere. While he often shouts or expresses explicit anger, here he adopts a friendlier voice, wishing the country good morning or offering gentle reminders to vote for the PVV. Is he playing innocent? Or is this ‘innocence’ a recurring theme in Wilders’ political communication, and the response of his supporters, who post racist imagery and comments in response, exactly what he is aiming for?

Wilders might seem reckless, but I’d argue that he’s deliberate and cautious. He pushes the boundaries of expression, and makes sure that, when faced with criticism, he has a counter argument. In 2014, during municipal election night, he asked the audience whether they wanted ‘more or fewer Moroccans’. The audience responded by shouting ‘Fewer! Fewer!’ This led to a six-year trial on the limits of freedom of speech: he was convicted of inciting discrimination and group insult but received no punishment. Here a mechanism similar to his use of the AI images emerged. Wilders simply posed a question (equivalent to posting the ‘innocent’ image), and the audience response made its discriminatory undertone explicit (like the people generating racist fantasies in response to the images of families). This form of interplay between Wilders and his audience is something he actively employs as a mechanism. He knows that his audience understands the underlying, often racist, thought behind what he says, and so he uses framing through rhetorical questions, humour, and carefully chosen words, ensuring that he can never be held directly accountable while his supporters do the dirty work. Wilders uses the power of images to appeal to our imagination. The image represents something without him having to put words to it. In this strategy of interplay between the audience and himself, Wilders depends on his supporters, who he sets in motion every time he shares something through the social network.

Belgian author and cultural scientist Ico Maly examines how far-right discourse has been radically transformed and gained global influence, approaching this through a metapolitical lens.Ico Maly, Metapolitics, Algorithms and Violence: New Right Activism and Terrorism in the Attention Economy (Routledge, 2024). He makes the case that we should ‘understand the contemporary new right as a transnational, polycentric and layered micro-population constructed around political influencers, websites, fora and social media accounts. All those metapolitical producers function as centres of normativity.’Maly, 147. Central to his argument is that the rise of the global new right cannot be understood without the concept of Metapolitics 2.0.Maly, 10. This concept describes the alignment of metapolitical cultural struggle (aimed at securing cultural hegemony) with the ideologies and infrastructures of digital media. New right actors or agents, now not only intellectuals but also prosumers and influencers,Maly, 81. strategically leverage the algorithmic logic and affordances of platforms such as YouTube and Facebook to normalise and disseminate their ideas.Maly, 9-10. In doing so, they contribute to the construction of a post-liberal society and to the rise of far-right activism and violence.Maly, 9-10.

Maly shows that every form of digital interaction is a reinforcement of the original thought. The digital world, then, can be seen as an ecosystem in which Wilders is surrounded by other supportive agents, who all repeat and spread the same message in their own way. The digital world and mainstream digital media are not only places where conversations take place – they’re organisations that facilitate and actively organise, circulate, and moderate content. They have an enormous role in making political ideologies visible or invisible. They organise and structure the public sphere.Maly, 251-294.

Thanks to Maly, I understand that recognising this strategy of influencing public opinion through the digital media is more difficult than if it were spread on a physical stage.

As a Dutch citizen, I’ve become accustomed to Wilders’ social media behaviour. The way he and other politicians use social media for political gain has, unfortunately, long been the norm. And yet, these AI-generated images felt like a new level of communication. How can it be that an ‘innocent’-looking family photo results in reactions containing extreme, racist images, specifically of stereotypical Islamophobic fantasies?

Using AI to shape certain stereotypes is not new, especially within the support base of far-right parties. These images are primarily found on private Facebook pages, never on official PVV accounts.Eva Hofman and Joris Veerbeek, ‘De Kunstmatig Ontworpen Werkelijkheid van de PVV - Het Land van de Hoogblonde Gezinnetjes,’ De Groene Amsterdammer, 11 December 2024. These private Facebook pages are ‘fan pages’ where almost all shared images are AI-generated. The difference with Wilders’ official account is that on these pages, explicitly misleading images of hordes of ‘dangerous and extremist’ migrants (always people of colour) are mixed with images of Wilders as a superhero,

his political opponents, and the radiantly smiling white families. These fan pages appeal to our imagination differently than official accounts, where there’s more caution regarding the types of images that are shared and a greater awareness of potential consequences. Both platforms are aware of their audience, consider who’s watching, and adjust the level of extremity accordingly.

In 2024, investigative journalists discovered that some of these ‘fan pages’ are run by at least two members of parliament from the PVV.Hofman and Veerbeek, ‘De Kunstmatig Ontworpen Werkelijkheid’. A very recent investigation also revealed which prompts were used to generate the images shared on the pages.Eva Hofman and Joris Veerbeek, ‘Vanuit de Pvv-Fractie Worden in Het Geheim Met AI Racistische Ideeën Gepromoot,’ De Groene Amsterdammer, 11 October 2025. Remarkably, the racist, sexist elements do not explicitly appear in the prompts themselves but rather in the images that are ultimately produced. Nevertheless, when Wilders was asked to disclose the prompts that were used for generating the ‘perfect families’, this request was refused.Robert van de Griend, ‘Met Blonde Vrouwen Zet Wilders Zijn Boodschap Kracht Bij: “In Radicaal-Rechtse Context Is Blond Vaak Het Symbool Voor Zuiverheid”’, De Volkskrant, 18 June 2024.

As an experiment, in November 2024, I appropriated the language from the 2023 PVV political manifesto. I fed every chapter to AI (ChatGPT, version DALL-E 3) and asked it to generate an image out of it. While doing this, I often got stuck in the rules of the AI machine. I repeatedly received messages that my request violated ChatGPT’s guidelines and had to adjust my prompt. Ironically, the AI itself indicated that my prompts were too explicitly racist or sexist. I therefore assume that whoever generated these images had to avoid explicitly racist prompts. After eventually succeeding, I replaced the original images with the AI-generated ones and created a second version of the PVV political manifesto. What should also be noted here is how AI, even without prompts, generates images that contain racist patterns or stereotypes, because its training data relies on images that exist on the internet, which themselves reflect a long history of cultural and racial bias.Leonardo Nicoletti and Dina Bass, ‘Humans Are Biased. Generative AI Is Even Worse’, 9 June 2023.

Here's is my Experiment 1. Caption titles align with certain chapters from the PVV manifesto:

So we have a political manifesto that actively uses racist language, arguably prompting its readers’ imaginations. And we have two different types of social media accounts where AI-generated images are shared: fan pages and Wilders’ personal account. The fan pages controlled by prominent PVV members share explicitly racist imaginations. They were generated with prompts that had to avoid explicit language, yet the resulting images are overtly racist. Since I tried to make similar imaginations, drawn from the language of the manifesto, and got stuck, we can assume that in generating the perfect families, explicit language was also carefully avoided.

This shows how generative AI can operationalise racism without ever naming it while facilitating the avoidance of direct responsibility. AI serves as an amplifier of far-right ideology by allowing imagination itself to be a political instrument, through fabrications of a visual world that reinforce fear, purity, and exclusion.See Maly, Metapolitics, 173. Operating not through abstract phenomena but through familiarity, innocence, and humour, it is possible to be a racist in disguise.

Salvatore Romano, head of research at and co-founder of AI Forensics, a European nonprofit organisation that investigates, exposes, and shares how algorithm-based systems and AI tools influence our lives, notes that what we’re currently seeing on the accounts of these politicians is just the tip of the iceberg. What’s being generated by individuals, beyond the ‘official’ channels, is far worse.Ben Quinn and Dan Milmo, ‘How the Far Right Is Weaponising AI-Generated Content in Europe,’ The Guardian, 26 November 2024. In the depths of Facebook fan pages, and in the comment sections of Wilders’ X account, a ‘creative’ breeding ground of sorts is activated each time an imagination of a perfect family is shared.

Investigating the PVV imaginations left me with a nauseous feeling. The perfect little families staring at me with their frozen smiles was unnerving. Is this the visualisation of Dutch identity that Wilders so often speaks of?

According to Romano, the use of AI-generated images has so far mainly been confined to the far-right side of the political spectrum.Quinn and Milmo, ‘Far Right’. If this remains the case, and other parties stay far away from it, then aside from being a problematic but nevertheless strategic or distinctive way of campaigning, it could also serve as a tool for recognising far-right messaging and imagery. What it certainly shows is that we’re all the more obligated to develop legislation around AI and media literacy, and that engagement with these issues shouldn’t be reserved solely for visual practitioners like me.

Experiment 5: February 2026, An attempt to deconstruct the “innocent” white blonde woman through collage. A collage of the blonde women shared by Geert Wilders’ party (PVV) as well as another far-right Dutch party (FVD), combined with a real photo from my own archive.

A personal end note on the visual experiments

These five visual experiments grew out of my ongoing conversations with the editors about responsibility, representation, and energy use. At first, I questioned whether it was even necessary to show these AI-generated images, given their experimental nature and the environmental footprint of generative systems. The editors shared these concerns, and we discussed it at length. In the end, we decided to include a limited selection, because I felt they are essential for understanding the mechanics I explore in the essay: how AI can turn ideological language into visual form, often without any explicit prompts.

Where relevant, the captions provide context for the images and acknowledge the energy and ecological costs of generative image production. I want to be clear: these works are not endorsements of the aesthetics they reproduce. They are critical experiments, investigations into how artificial intelligence can amplify political imaginaries, and how quickly something that appears innocent can be used as a vehicle for exclusion.

---

This article forms part of Networking the Audience, a themed online publication guest-edited by Will Boase and Andrea Stultiens, developed in collaboration with MAPS (Master of Photography & Society) at KABK The Hague. The contributions emerge from an open call shared across the MAPS network, including alumni, and bring together artistic and critical perspectives on photography, publishing, and circulation. Together, the nine contributions reflect on how digital systems reshape authorship, readership, and meaning-making, foregrounding publishing itself as a creative and relational practice. Rather than addressing a fixed audience, the series explores how images and texts move through fluid, networked publics.