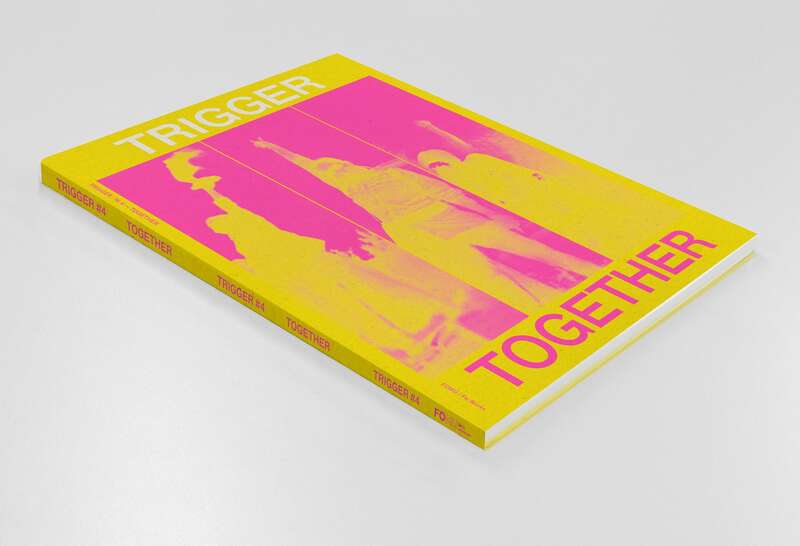

Cover image designed by Hans Gremmen, Fw:Books

Release and Launch of Trigger #4: Together

Editor's note. This post has all the information on the content and example spreads, the launch, and the purchase of Trigger #4 Together. It starts with the editorial, which is co-authored by our guest-editors named below.

Rein Deslé, Susan Meiselas, Anne Ruygt, Sumeja Tulic, Tom Viaene

09 jan. 2023 • 10 min

Introduction

Trigger is an online and print publication published by FOMU and Fw:Books (Amsterdam). The magazine takes photography as a starting point for criticism, long reads, contemporary and historical research and artist contributions. Every year, in November, Trigger also publishes a themed issue in collaboration with a guest editor. For its fourth issue, Trigger #4: Together, Trigger collaborated with photographer Susan Meiselas, who helped design and compile it. This issue is exceptionally published in February 2023.

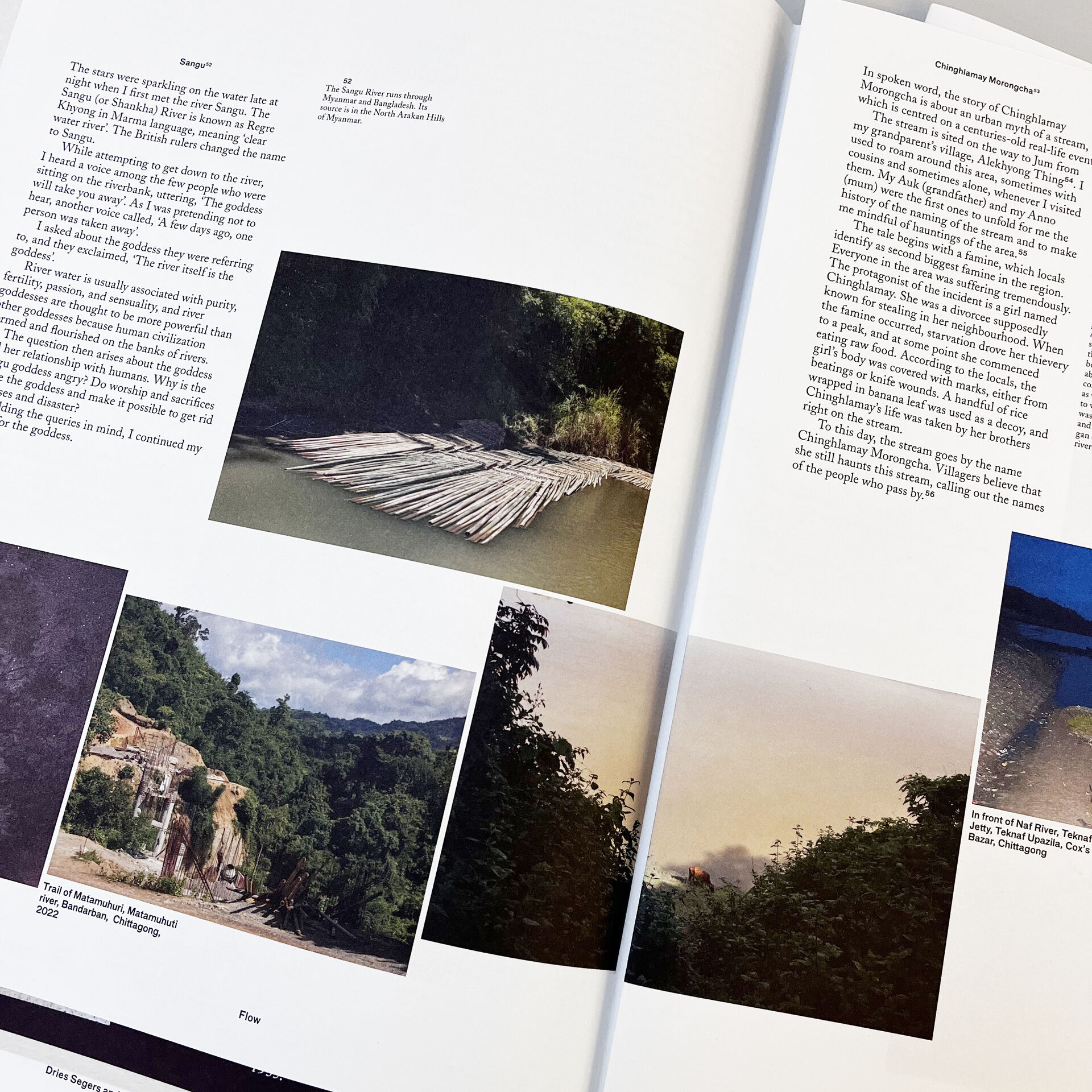

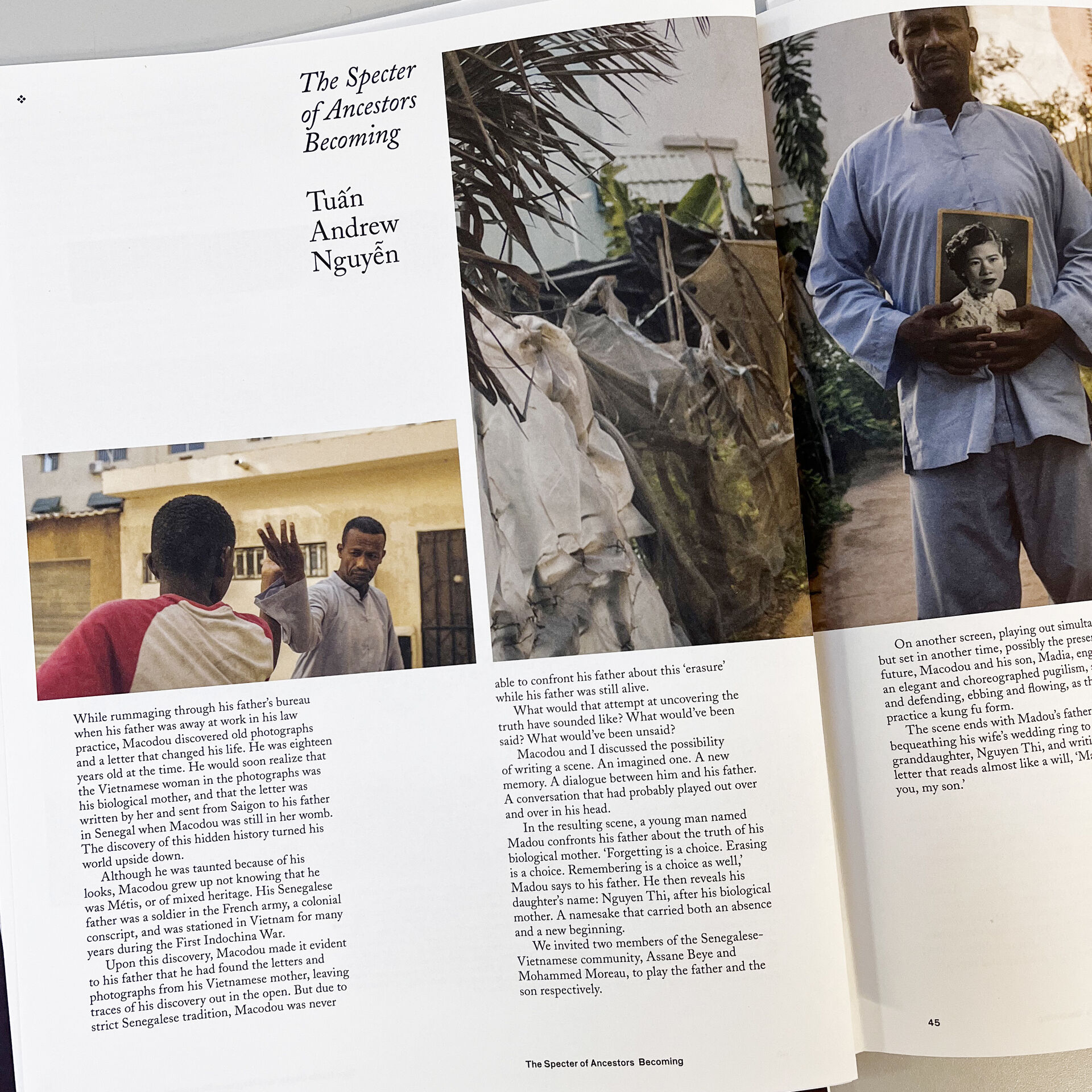

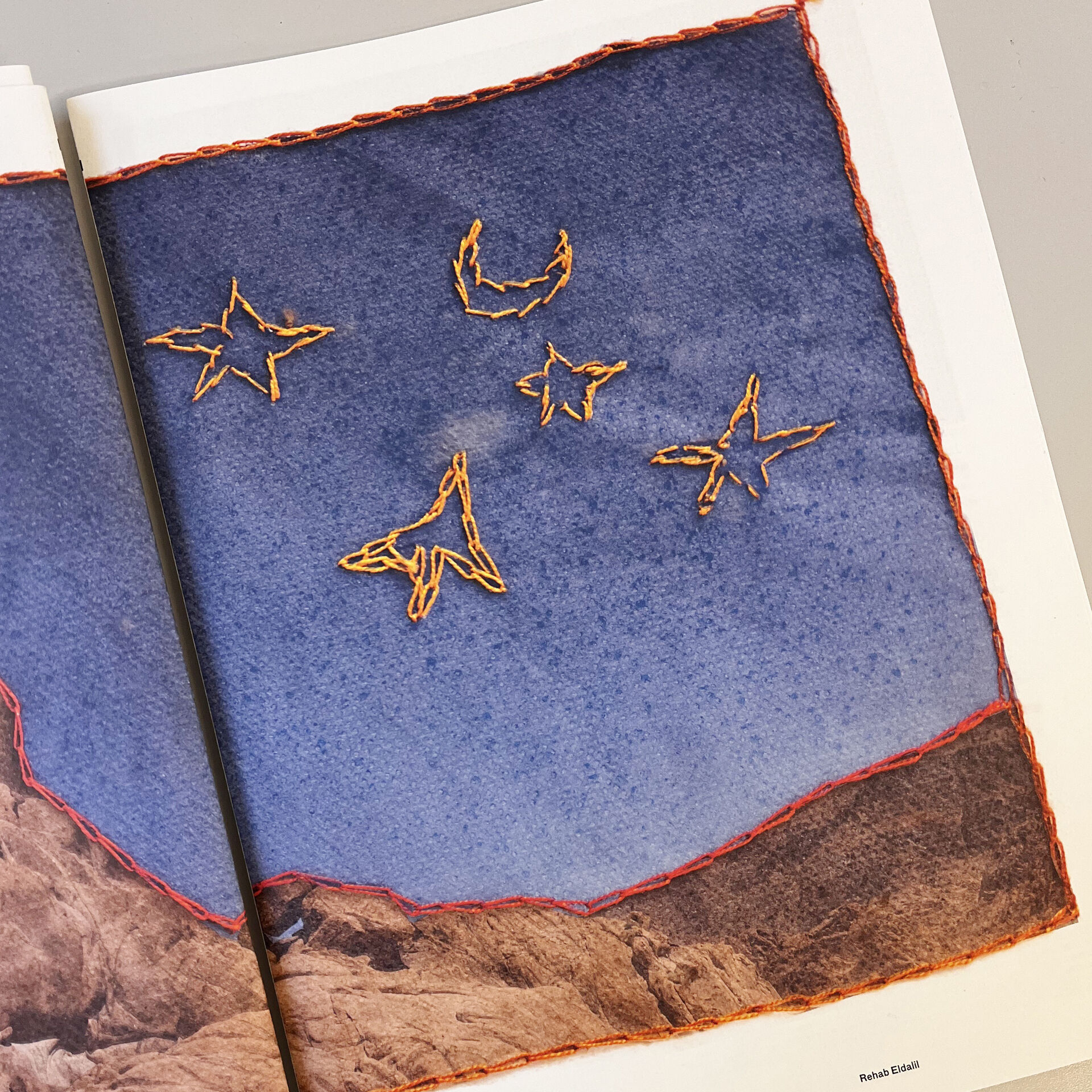

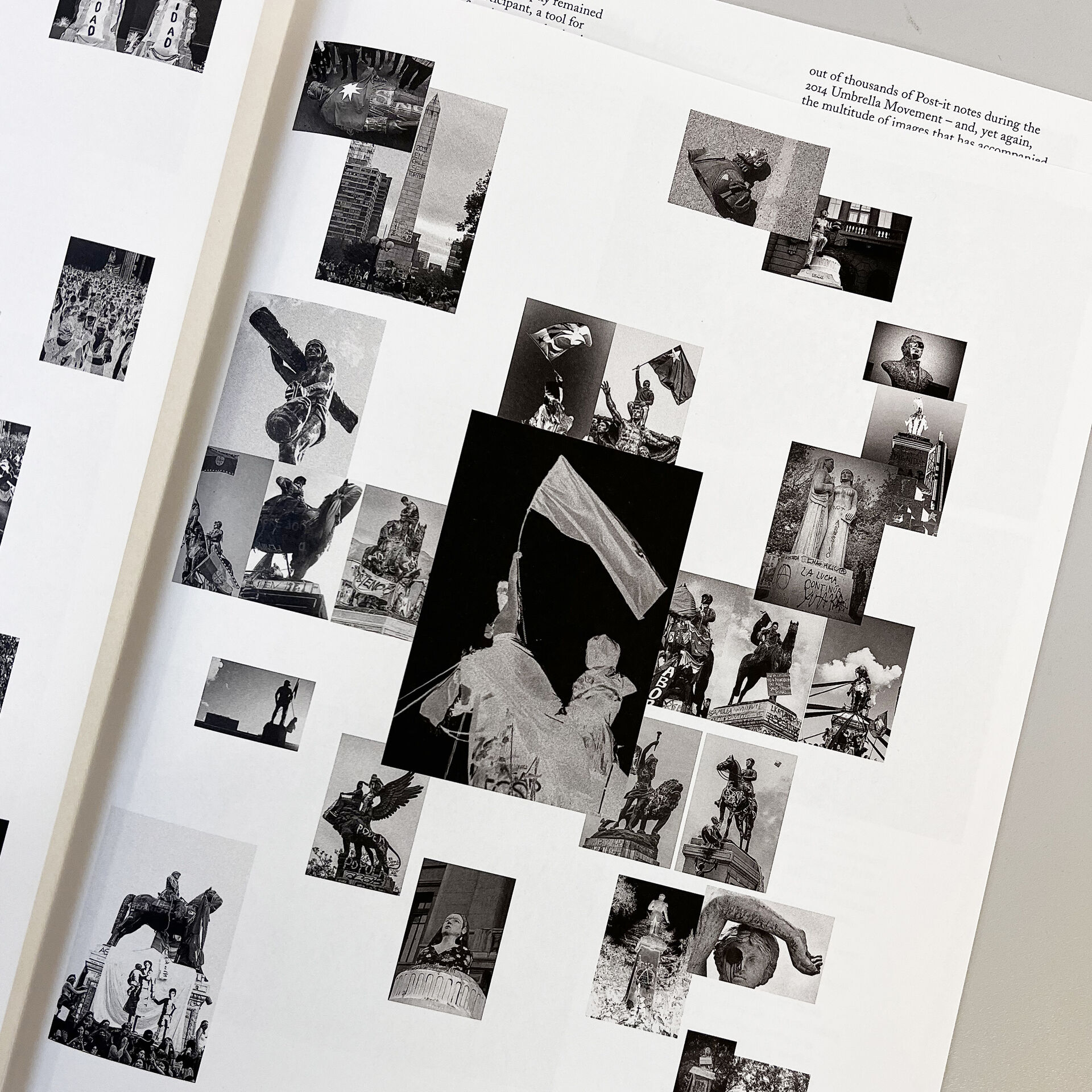

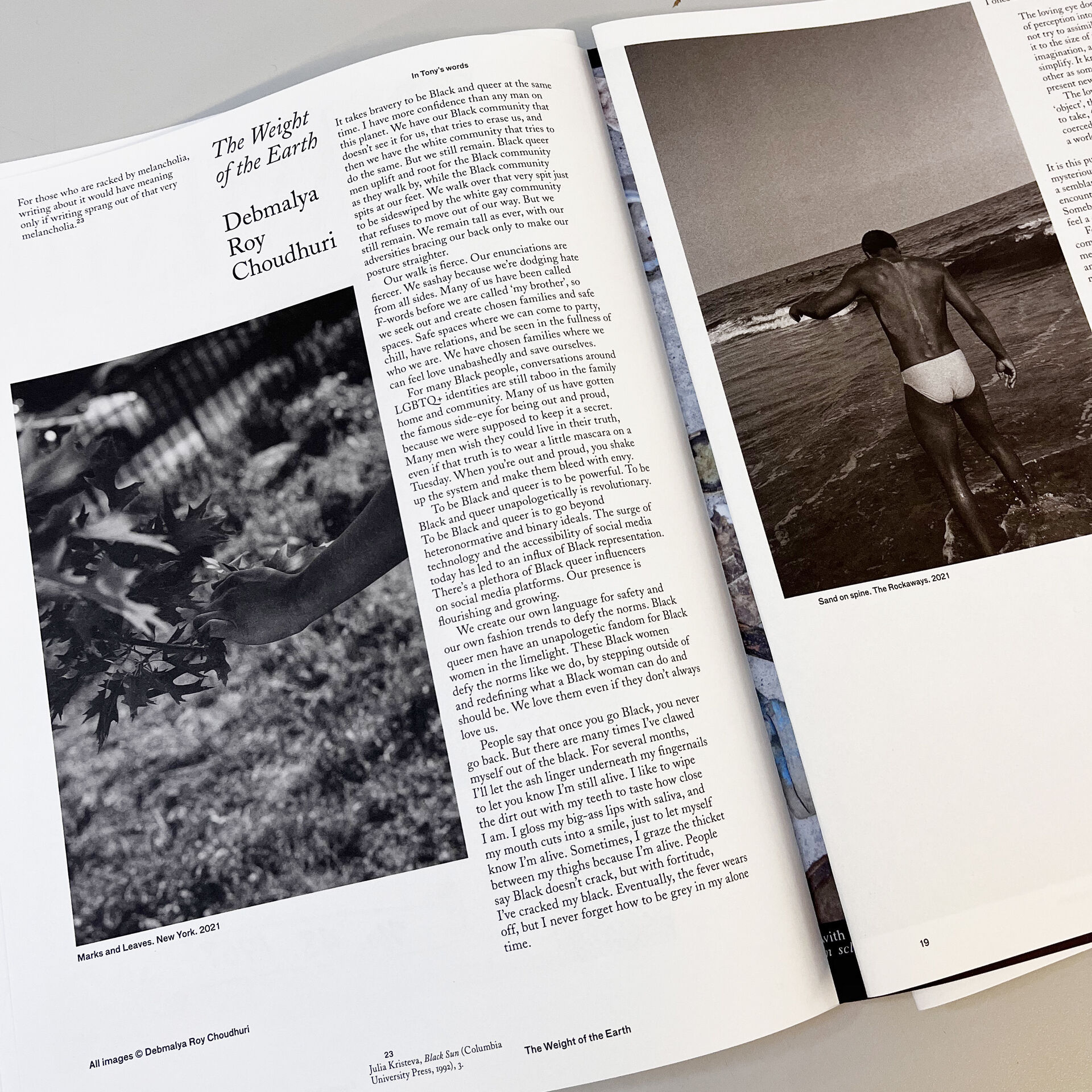

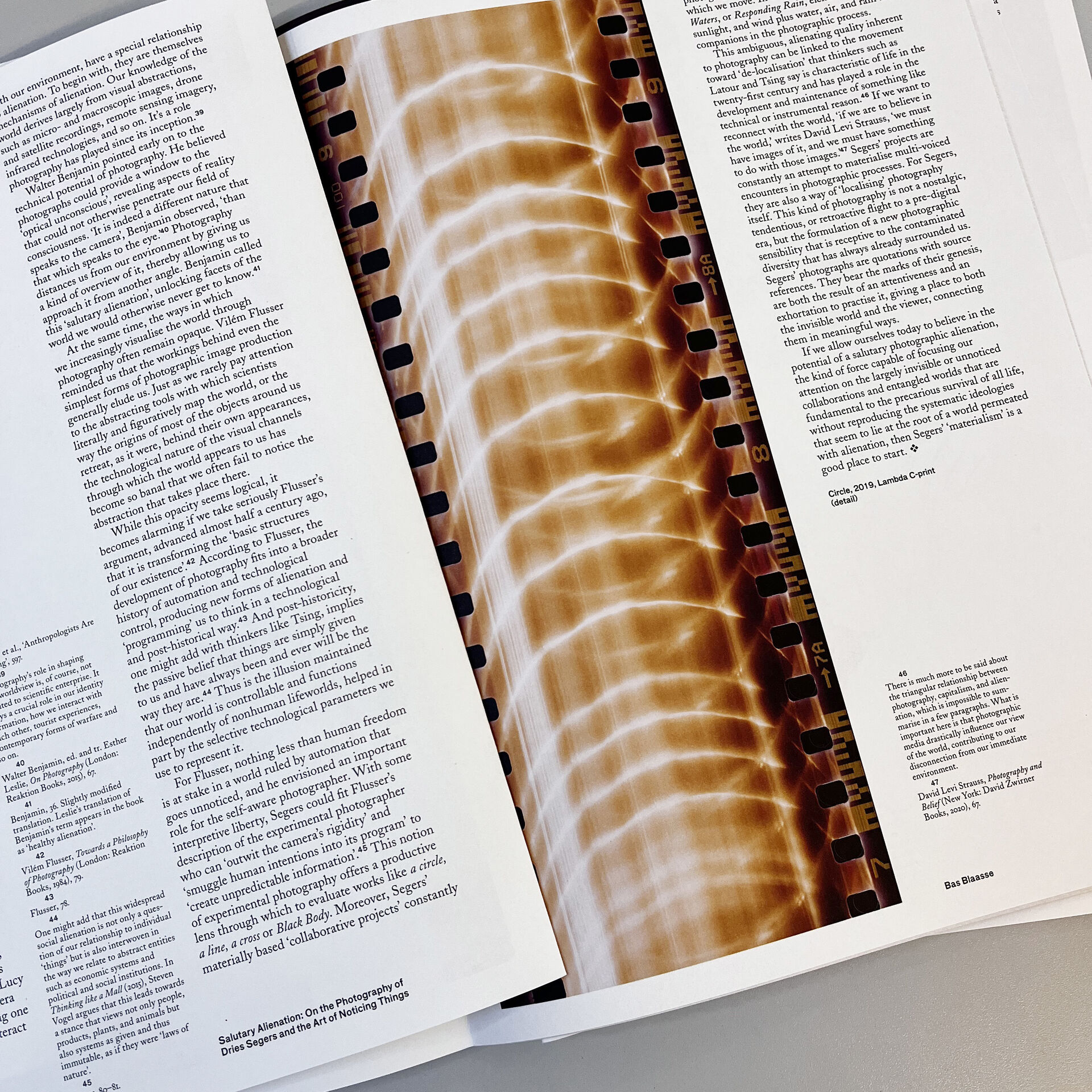

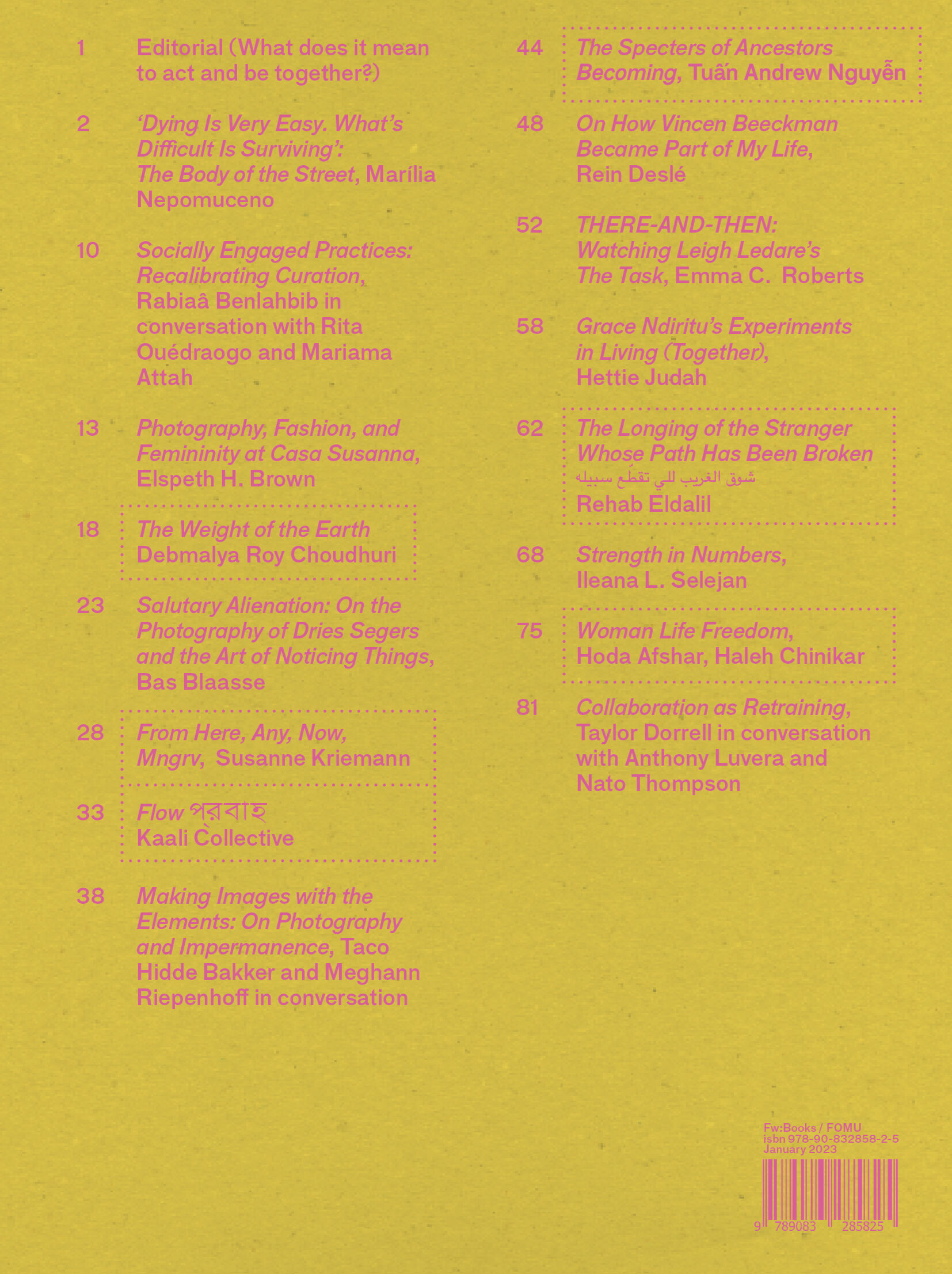

Trigger #4: Together explores various forms of collaboration in photography. Sixteen contributions engage with strategies of co-creation that stretch notions of authorship and ownership, breaking through existing heteronormative, state-owned, or hyper-individual categories. In this issue, you can find essays by internationally renowned researchers and writers such as Elspeth Brown, Ileana Selejan and Hettie Judah. It further gives an insight into the forms of collaboration and community in diverse photography practices by Jonathas de Andrade, Grace Ndiritu, Leigh Ledare, Dries Segers, Meghann Riepenhoff and Vincen Beeckman. You can also read some conversations between photographers, critics and curators about socially engaged photography and curating. Rabiaâ Benlahbib and Taylor Dorrell each go out and talk with two different people from different generations, genders and backgrounds, working in the broader field of socially engaged practices. When comparing both conversations, a small history pops up of the changing role of the curator since the 1990s. Nato Thompson would have ‘curator’ changed in ‘infrastructure builder’. Both Rita Ouédraogo and Mariama Attah on their part, see a crucial role for the curator as caregiver in making sure the focus is on ‘togethering’ as a process. Last but not least, a large part of this issue consists of artists and photographers such as Debmalya Roy Choudhuri, Susanne Kriemann, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Kaali Collective, Rehab Eldalil, Hoda Afshar and Anthony Luvera, who have repurposed existing work in answering our 'call for collaboration'.

Editorial: What does it mean to be and act together?

The following is the editorial from our upcoming issue Trigger#4: Together. The editors and guest-editors both highlight the broader context that led to this issue and the main questions the contributors deal with in this issue.

When we sat down to work together on Trigger #4: Together, we wanted to openly venture into what we personally regarded as true, urgent, hopeful, and critical forms of togetherness through and in photography.

While collaborative practices aren’t new to documentary photography, the national, environmental, and digital contexts in which people are ‘making together’ have been changing so much. The challenges of global inequalities and environmental justice, flows of migration, processes of gentrification, the ebb and flow in the recognition of Indigenous identities and cultural heritages, and the rise of artificial intelligence have all made more urgent the need to question myths and ideologies related to photographic authorship.

Documentary photography and socially engaged art have come closer to one another. Increasingly, photographers are integrating participatory, collaborative practices into their documentary projects. This runs parallel to the recent history of the visual arts, where, since the 1990s, a so-called ‘collaborative turn’ has shown a growing focus on social justice, the use of art as a tool for activism, and the willingness to deal with complex ethical questions that arise as a result of an explicit intention to work with people. In photography, this has led to a growing concern about the ‘truth value’ of documentary material.

If our issue taps into this long-noted turn, it does so in a modest way while calling attention to the ‘politics’ of making together, especially regarding the representation of gender, colonial appropriation, institutional subversion, and authorship.Recent, extensive research has happened through the work of authors and artists like Daniel Palmer (Photography and Collaboration, 2017), Gemma-Rose Turnbull (asocialpractice.com), and Kelly Hussey-Smith. Anthony Luvera, who is a kind of forerunner in what’s called ‘collaborative photography’ today and whose voice is also in this issue, has a whole periodical about socially engaged photography, called Photography For Whom? And Susan Meiselas is currently wrapping up a long-term project culminating in a book on ‘a potential history of photography explored through the lens of collaboration’, together with Wendy Ewald, Ariella Azoulay, Laura Wexler, and Leigh Raiford (forthcoming 2023). With all the buzz around ‘collaboration’ these days, we were wary of three issues. First, crisis upon crisis, the increasing precarity of modern life, seem to be forcing people into ‘working together’. The intense globalisation of the last thirty years, the widespread penetration of neoliberal rationality, the dissolution of political structures in climate-affected areas, and mass migration have not helped this precarity, throwing many people into a state of permanent displacement. This is, on the other hand, an indirect breeding ground for new imaginaries concerning supranational solidarity structures, democratic ownership, and resource governance.See Aleksandra Savanović, ‘After Modernity: Citizenship Beyond the Nation State?’, Green European Journal, 26 May 2021, https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/after-modernity-citizenship-beyond-the-nation-state/

What makes ‘together’ then feel urgent and potent enough, in a world where nations seem to thrive on old notions of ‘citizenship’? Second, a lot of collaborative projects hide tensions, rivalries, and antagonisms. Does togetherness always have to come from a full embrace or acceptance; can’t it be an act of refusal? Finally, the ‘collaborative turn’ can be understood as a critique of the Western documentary tradition. Working in dialogue with and from within a community seems to have become a requirement for photographers. But collaboration in itself does not exclude forms of exploitation, as Ariella Azoulay has shown. How can ’together’ go beyond good intentions?

We basically followed through on the noted conceptual shift, that is, from ‘photography as something that begins and ends with an individual photographer’s vision of the world to . . . photography as a social process involving the co-laboring of photographers, their subjects, and viewers over time.’Daniel Palmer, Photography and Collaboration: From Conceptual Art to Crowdsourcing (Routledge, 2017), 18. Initially, our discussions took a cue from the gains, challenges, and promises that collaborative multi-authored practices bring to the photo world. Each of us ventured out searching for artistic positions we considered valuable in helping us broaden our vision, tapping into a pool of experts, curators, and researchers who inspired us with what they regarded as imaginative forms of togetherness through photography.Here we’d like to thank for their input and thoughts Sumeja Tulic, Lisa Rosendahl, Tanvi Mishra, Kobena Mercer, xtine burrough, Susan Best, Anjalie Dalal-Clayton, Liz Wells, Bindi Vora, Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Jörg Colberg, and Kester Grant, among others.

As we were more interested in performing ‘forms of togetherness’ through the publication itself, we wanted to do something other than showcasing ‘best practices’.This choice feels unavoidable after understanding the curatorial approach behind documenta fifteen (https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/), which is in a way a response to the ‘Western’ practice of showcasing separate art works. Their decolonial, decentralized practice of ‘lumbung’ refers to a collective pot of sharing that holds a community together. Lumbung is a totally different curatorial way of working together, instigated by ruangrupa (https://ruangrupa.id/en/) and the artistic team. See documenta fifteen Handbook (HatjeCantz, 2022). documenta fifteen shows clearly that discussing ‘togetherness’ and collectivity in an arts context is meaningless if one doesn’t tackle questions of economic survival and autonomy. That’s also why, in circling above our topic,To rephrase Roland Barthes’ justification of his own presentation in How to Live Together (Columbia University Press, 2013), 21. we have more text-as-image, personal fragments, cuts, and ‘stilled’ images than full artistic projects depicted as wholes in this issue.This issue explores other forms of togetherness in the form itself, from still images, reproducing an iconic whole, to stilled images, sampling and cutting, to find a balance between visibility and obscurity. In his conversation with David Campany on the difference between still and stilled images, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa points to Denise Ferreira da Silva’s suggestion that ‘there is creative work to be done in the wake of that scene [the killing of George Floyd], which need not include its reproduction’. It calls for new images, new initiatives around how to make visible the state’s ‘total violence’. That process, according to Wolukau-Wanambwa, ‘cannot be static, just as the image cannot ultimately stand still’. He refers to Rabih Mroué’s The Pixelated Revolution (2012) where ‘incompletion’ marks the relationship between the footage and the event, where the ‘cuts’ enacted in the footage charged them as ‘stilled’ images. See David Campany and Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, ‘Fabulation, Fragmentation, and the Freeze Frame’, in Indeterminacy: Thoughts on Time, the Image and Race(ism) (Mack, 2022), 40–57.

To the writers, artists, and photographers we worked with, two questions stood out: How do you envision making together in terms of co-authoring? And how does making together engender forms of togetherness?

The contributions hinted at togetherness as a method (i.e., a means of co-authoring), a goal (i.e., a way to reimagine relationships, communities, and curation), and a necessity (i.e., a means of surviving, reconnecting, redistributing, and rebuilding). Without the necessity, one would fall back to a state of being together for the sake of being together.

Making together means artists working with artists and artists working with ‘others’, who might be community members, neighbours, family, lovers, children, or even the natural elements. Here, the strategies of co-creation stretch notions of ownership, breaking through existing heteronormative, state-owned, or hyper-individual categories.

Togetherness, in this issue, leads in different and often opposing directions. ‘Together’ can be bordered (e.g., through communities, neighbourhoods, rivers, soils), but it can also thrive in the borderlands (e.g., in mangroves, memories, fungi’s mycelial networks, trans* identities). Forms of togetherness cast their shadows on the futures we can imagine together. Such spectres make the concept both a fugitive dream and an ever-present burden. Togetherness is both a response of repair to damages done and an act of disobedience to state-engineered forms of forgetfulness.

A photographer recruits multiple voices in the production of photographs, with the aim of creating more inclusive forms of records. This goes from democratising the making of photography by involving communities in their own representation to decolonizing practices by focusing on supranational forms of togetherness – temporary institutions and communities of un-belonging – and bringing together individuals with different knowledge and experience in a collaborative process or project to form hybrid, experimental communities.

To end on a fun note. In her The End of Capitalism (2006), economist J. K. Gibson-Graham states, ‘But what sense is there in denying the ample evidence that people have the capacity to experience extraordinary joy and pleasure in working with each other simply because they are working together: the giddy sensation that one is smaller than what one thought (a part of a whole) and larger than what one is (stripped of individual fetters), that one has become folded, along with others, into a new creature altogether.’ We hope you get some of that giddy sensation as you leaf through this issue – we surely felt it in compiling it. Even more so, we hope you find reasons and strategies to be folded into a new creature altogether: yourself.

Launch Event

Trigger #4: Together will be launched on two occasions.

First, at Cloud Nine (Utrecht, Netherlands) during the Fotodok Book talks on Thursday night February 9. More on that program, check here.

Second, at FOMU (Antwerp, Belgium) on wednesday night February 15 during Susan Meiselas' artist talk. More on that program, check here.

Online Shop

You can (pre-)order your copy through FOMU's online shop here for 21 euros.