Felix Gonzalez-Torres

"Untitled", 1991

Billboard

Dimensions vary with installation

Installed at Pennsylvania Avenue near Fulton Street, Brooklyn. One of six outdoor billboard locations throughout the New York City area, with 1 indoor location, as part of the exhibition Print/Out. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, NY. 19 Feb. – 14 May 2012. Cur. Christopher Cherix. Catalogue. [With outdoor billboards on display 20 Feb. – 18 Mar. 2012.]

Photographer: David Allison

© Estate Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Trauma in the Frame

In this text, I explore how trauma is stored in our bodies and how it manifests in art and photography. Drawing on Wilhelm Reich’s concept of ‘character armour’, which suggests that our bodies develop protective layers against emotional pain, I start by examining an unexpected photograph of Kurt Cobain in one of Reich’s ‘energy boxes’. From there, I delve into how artists like Felix Gonzalez-Torres have integrated their personal traumas into their work. I argue that photography can capture unconscious trauma, and I conclude with a reflection on sexual liberation – especially within a queer context – and the critical role photography still plays in this ongoing struggle.

Simen K. Lambrecht

16 mrt. 2025 • 15 min

Luca Guadagnino’s recently released film Queer is a study of longing and alienation, steeped in trauma. Based on William S. Burroughs’ once-forgotten autobiographical novel, the film follows Lee, a romanticised wreck of a man searching for some utopian soulmate. The film delves into the deep emotional wounds of Burroughs himself, who once admitted that his writing was a way of wrestling with the past, particularly the tragic moment in 1951 when he drunkenly shot and killed Joan Vollmer. Burroughs’ trauma is relayed in the film set in some air castle version of Mexico City,The same place where Burroughs killed Vollmer, his common-law wife. where reality and fiction play tag. Lee’s behaviour can be seen as a direct translation of his internal suffering, manifesting itself in his body.

How could it not?

Wilhelm Reich, an Austrian psychoanalyst and provocative figure in the history of psychology, was a big inspiration to Burroughs, introduced the concepts of ‘character armour’Described by Olivia Laing:: “He thought this character armour, as he called it, was a defence against feeling, especially anxiety, rage and sexual excitement. If feelings were too painful and distressing, if emotional expression was forbidden or sexual desire prohibited, then the only alternative was to tense up and lock it away. This process created a physical shield around the vulnerable self, protecting it from pain at the cost of numbing it to pleasure.” - Olivia Lain, Everybody: A Book About Freedom (W .W. Norton & Company, 2021), 29-30 and, later, ‘muscular armour’.Reich called ‘character armour’ and ‘muscular armour “functionally identical”. - Wilhelm Reich, Character Analysis: Third, enlarged edition (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984), 352 His ideas significantly influenced our understanding of the intricate connection between physical and emotional experiences. Reich posited that the body functions as a repository for mental trauma, acting as armour to shield against additional emotional pain.

In my understanding of his early theories of this ‘armour’, the principle works in both directions: trauma is experienced and gets ingrained in our bodies, to then be translated into physical, bodily reactions. In parallel, we have internalised trauma that gets physically translated again. One comes from the exterior inwards and gets looped back out into what Reich describes as muscular attitudes, or chronic muscular spasms,Wilhelm Reich, Character Analysis: Third, enlarged edition (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984) while the other starts in the interior and becomes physical through our bodies.

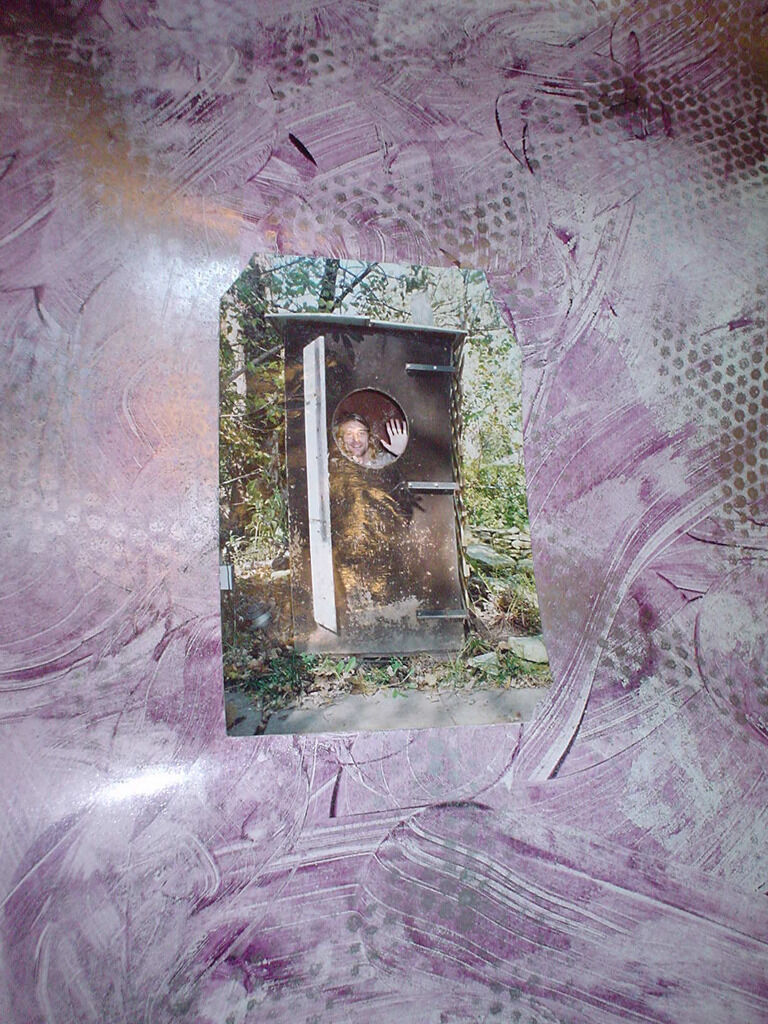

With Burroughs resurfacing in the body of actor Daniel Craig, Reich deserves a modest reawakening as well. Let’s start with a snapshot of Kurt Cobain.Nirvana is, not very coincidentally, featured on the soundtrack of Queer. There’s a rarely seen photograph of Cobain floating around on the internet. In it, he’s seen through a small, round window just big enough to encompass his face. He’s sitting in a wooden box in what seems to be a backyard. His hand is lifted, either simply touching the glass of the circular window or waving to the camera. He smiles sparingly into the lens. The saturated colours of the analogue photograph give off a warm energy; it’s a sunny day, and from the leaves, it looks like late summer. The whole scene has a laid-back, innocent, even slightly goofy ambience. It’s a photo mimicking a family album, and it goes against the image I had of a depressed, serious grunge-rock star. Why is Cobain smiling?

The photo was taken in Kansas in the United States, on Burroughs’ property. Burroughs is best known for his postmodern writings, such as the novel Queer and his shotgun art.Burroughs shot spray paint cans taped to a canvas with a shotgun to create abstract paintings. The photo is dated six months prior to Cobain’s suicide. The wooden box he sits in is Burroughs’ personal ‘orgone accumulator’, a device invented by Reich around 1940 to absorb orgone energy. Burroughs was a big fan of Reich, especially the connection Reich made between psyche and soma. The idea of ‘orgone energy’, as Reich called it, stemmed from Sigmund Freud’s research into neurosisMental disorders caused by past anxiety or trauma, according to Freud.https://www.cla.purdue.edu/academic/english/theory/psychoanalysis/freud4.html in humans. Reich, however, believed that libidinal energy was rather the primal energy of human life. Traumatic experiences could block this energy and lead to physical and mental illness. Reich made the accumulator to improve the patient’s mental health. Was this why Cobain – someone who struggled with mental health – sat in the wood-and-metal box?

Cobain, in turn, was an outspoken admirer of Burroughs, who served as an inspiration for many of Cobain’s songs. They even collaborated in 1992, but the pair met for the first, and only, time 30 years ago in ’93. The warmth I first read in the photo is offset by Burroughs recalling their meeting: ‘The thing I remember about him is the deathly grey complexion of his cheeks. It wasn’t an act of will for Kurt to kill himself. As far as I was concerned, he was dead already.’Christopher Sandford, Kurt Cobain (Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004). Why was Cobain photographed in the orgone box? Did Burroughs tell him to use the box, and did he take the photo? Was Cobain there to meet his hero and talk about his struggle with depression? Did Burroughs offer him advice?

If Cobain tried to regain some of his health through a regime of concentrated orgone energy, it clearly didn’t work. And it wasn’t his fault. Reich was controversial throughout his life and became increasingly ungrounded as he moved away from his home in Europe. He was, as Olivia Laing recounted in her acclaimed Everybody, ‘a man who dedicated his life to understanding the vexed relationship between bodies and freedom’.Olivia Laing, Everybody: A Book about Freedom (Picador, 2022). Once Freud’s most promising protégé, he soon developed his own theories on sexuality and trauma. He suspected his patients carried past trauma in their bodies, freezing when certain areas would be touched or stroked, as if they were walking around with an emotional armour on their skin. He first developed his theory in the 1920s and was an absolute pioneer in how we think about body-based psychotherapy. He was also a complex and multifaceted character – as much an outsider as a pioneer, as progressive as he was conservative, a fantasist and a scientist, a protégé who ended up on the periphery of history. But with the right nuance, some of his convictions have retained their value and stay irrefutably relevant.

Today it seems quite normal to think of physical consequences from mental distress. Within the definition of emotion already lies the link to our physical presence. As Merriam Webster defines it, ‘emotion’ is ‘a conscious mental reaction (such as anger or fear) subjectively experienced as strong feeling usually directed toward a specific object and typically accompanied by physiological and behavioural changes in the body’. Our body is the cloakroom for trauma.

For years, I had trouble relaxing when someone touched my back. It wasn’t a conscious decision to freeze up – my body did it for me. Massages were out of the question, as was soft stroking. I needed pressure, on the edge of pain, to feel comfortable getting touched. Later, during therapy, I learned that this was probably connected to a sexual trauma I suffered when I was 18, during a series of photoshoots as an aspiring model. My body protected me against the same stimuli by freezing up. If I tried to push it, I would lose control over my breathing, sometimes shake, and become totally impervious for some time. At the time, I didn’t talk about the trauma with anyone, but my body was already voicing the violence it had experienced.

Freud, once Reich’s mentor, understood that much of what is perceived goes unnoticed on a conscious level and is only later registered as part of our experience.

I remember clearly not remembering – I recall the lead-up and returning moments after. My body rusts into reality while my mind dissociates. Days (sometimes weeks) later my mind is pulled back, as if it were on a rubber band, and I get sick, tired, or miserable. Finding words for what has happened is hard, even now, but Reich was right to assume my body was venting everything already.

This concept prompted Freud to suggest the camera as a metaphor for mental processes – capable of capturing the unperceived, which only emerges when the film is developed.Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism: Three Essays (1939), in Standard Edition, 23:3–132. Parallel to Reich’s theory of trauma, photography, as memento mori, can therefore capture trauma that is only later registered when it is developed (or scanned or printed) and viewed. As photography leaves traces of a past present, trauma marks the unconscious and indexes it. These moments are ingrained in the negative and our subconscious – with the difference that we can view and reexperience the trauma within a frame (as Proust suggested) but have little control over the breaches caused by the trauma stored inside our bodies.

Many notable artists throughout history have delved into their personal experiences of trauma to create art. Pierre Molinier, Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, Larry Clark, Josef Sudek, Joel-Peter Witkin, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres are a few who spring to mind.

I’m focusing here on how male artists have dealt with (sexual) trauma. It's the most genuine and truthful way to address the subject, encapsulating my experience as a victim, a man, and an artist.

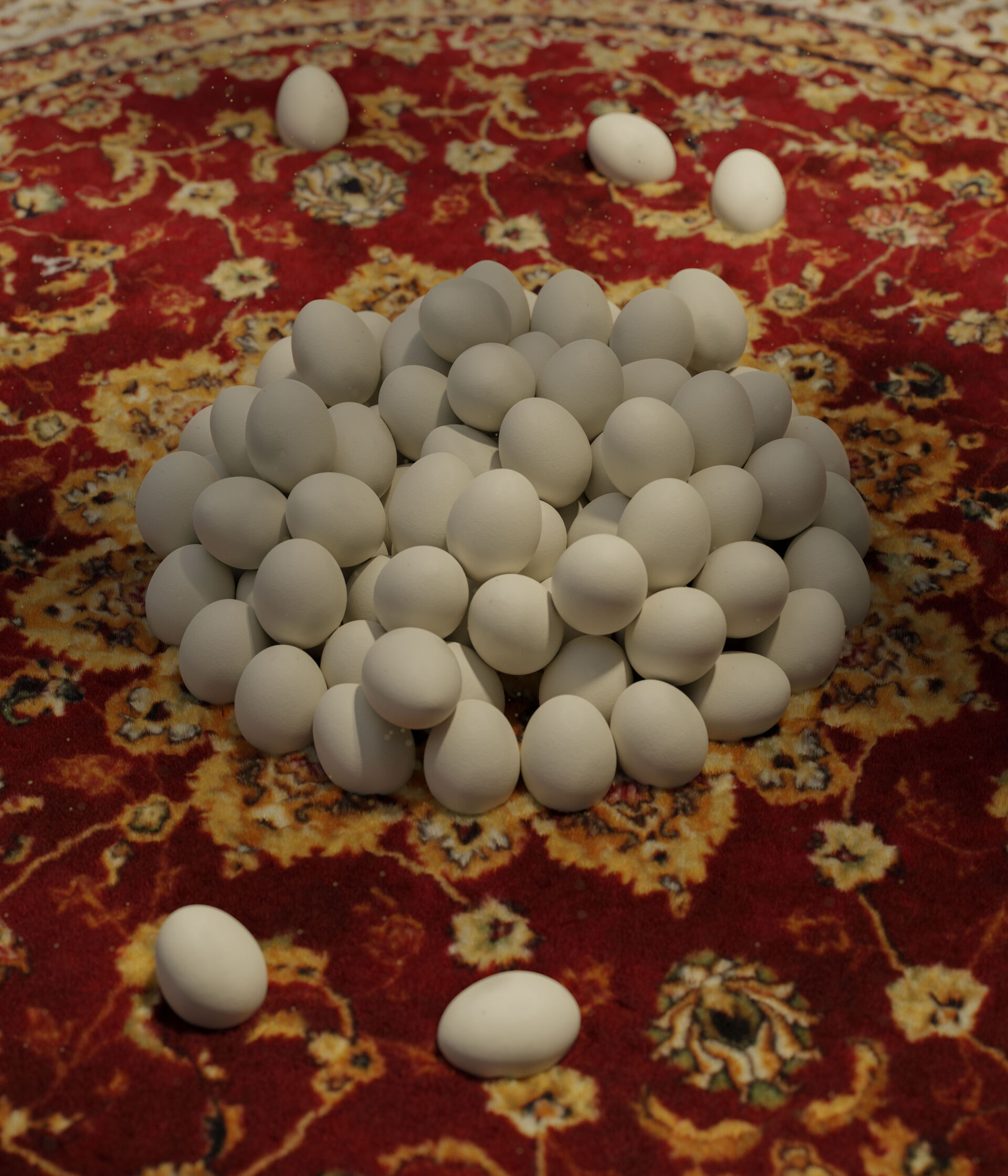

In her book Photography, Trace, and Trauma, Margaret Iversen describes how Gonzalez-Torres exhibited a single photo on a series of billboards across New York City in the early ’90s. The billboard, called "Untitled" (1991), depicted an unmade double bed adorned with two pillows that bore distinct impressions, seemingly reminiscent of the heads of a couple. The intimate and loving scene made public takes on a more sombre tone when you realize that the period of this work also marked the passing of Gonzalez-Torres’ partner, Ross Laycock. He succumbed to AIDS after enduring a long battle with the illness. In hindsight, this artwork operates as a memorial, celebrating their profound love and preserving its memory. However, interpreting the work solely through the lens of autobiography may be overly restrictive, as it possesses a distinct political dimension as well.

I’m unsure if Gonzalez-Torres strictly sought out to make a political statement, and I’m equally unsure if that really matters. It is one, and his initial intention is therefore of lesser importance. His work has always been seen as political, echoed in the 2021 exhibition The Politics of Relation at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, which described the translation of his love life within his work as one of his most political gestures, as it enabled him to talk about homosexuality openly.

"Untitled" (1991) serves as both a protest and a provocation. Its intimate portrayal and its public exhibition were exceptionally transgressive given the hysterical response in the US to the AIDS epidemic, which triggered vehement conservative backlash against the LGBTQIA+ community.

At the time, the term used was most likely ‘LGBT’, although it might have been more strictly the gay community that fell victim to the backlash, since mostly gay men were affected by the AIDS epidemic. For the sake of the article and consistency, I’m using the current term ‘LGBTQIA+’.

The work, paired with Gonzalez-Torres’ personal trauma at the loss of his partner, speaks therefore of a collective trauma of repression, effectively demonstrating what Reich realised decades earlier. Reich saw that his patients were not only suffering from bad childhood experiences; they were experiencing psychic disarray caused by an array of societal issues such as poverty, housing insecurity, unemployment, discrimination, and sexual repression. Reich’s patients were under pressure from both themselves and society. The two photographs I have discussed so far –

1. a memento of a long-awaited reunion foreshadowing a tragic death

2. a remembrance of a loving partner and a critic to an oppressive society

– seem to have little in common at first, apart from being made during the same period. Nevertheless, they share the same traces of trauma. The trauma, in this case, is not merely a historical backdrop but is embedded within the very fabric of the photographs themselves. One remembers, one predicts, encapsulating the human experience. And both fail to adhere to Reich’s utopia of liberation. Even in the face of love, intimacy, and adoration, liberation remains elusive.

My own traumatic experiences have let me to explore myself within photography more deeply. Photography has helped me progress and process further than words could do before. And I’m thankful for my trauma insofar as it set me on this path. (Not really, though – I would have preferred not to have needed trauma to start photographing.) I look back at captured trauma and let it collide with my present psyche to form something that holds integrity, beauty, fragility, and freedom. Or at least I try to. Moreover, the results are always mundane; they do not matter. As many have said before, the result, the product, is a mere impression of the value of the process, as it is a unique symbol of a unique experience. When I think about Gonzalez-Torres preparing the bed to photograph, thinking about his partner and the love they shared, I recognize the love as well as the shadowing trauma. In that moment, he’s both liberated and restrained, but the camera translates mostly trauma. We see absence rather than a fading presence, unless we look close enough.

When Reich spoke of a sexual liberation, he was reaching for something that would be still painfully relevant a century later. In parallel to many others, Reich was most likely influenced by his own trauma. His mother died by suicide when he was young after an abusive relationship with his father, exacerbated by his mother’s affair. (The affair only started due to the awful marriage in the first place.)Mary Katharine Tramontana, ‘The Long Fight for the Female Orgasm: Revisiting the Sexual Revolutionary Wilhelm Reich’, Esquire, 28 May 2021.https://www.esquire.com/uk/life/a36554013/fighting-for-the-female-orgasm-wilhelm-reich (Sexual) liberation was therefore personal for Reich, as he saw the far-reaching consequences a lack thereof could have. He firmly believed that his mother’s extramarital involvement stemmed from the amalgamation of marital discontentment interwoven with societal censure surrounding the prospect of divorce. In essence, he tried to transmute his own trauma, as well as that of his mother, into a catalyst for collective improvement. Yet Reich’s sexual revolution, however ground-breaking and innovative for its time, was mostly limited to a heterosexual status quo. He considered homosexual men ‘abnormal’ and homosexuality a compensation arising from an unconscious fear of women or other phobias.Thomas Antonic, ‘Genius and Genitality: William S. Burroughs Reading Wilhelm Reich’, Humanities 8, no. 2 (2019). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/8/2/101

It's hard to imagine how critical Reich would be of the queer spaces I enjoy frequenting, or of me as a whole. That’s beside the point I’m trying to make, and for the sake of our time here I won’t go further into it. Still,

with trans rights under vicious attack from the White House, we’re once again reminded that sexual revolution is not a single surge of energy but a continuous fight, and erotic liberation is essential to political emancipation. In Belgium, about ten percent of the population identifies as LGB+;Lotte De Schrijver, Elizaveta Fomenko, Barbara Krahé, Alexis Dewaele, Jonathan Harb, Erick Janssen, Joz Motmans, Kristien Roelens, Tom Vander Beken, and Ines Keygnaert, ‘An Assessment of the Proportion of LGB+ Persons in the Belgian Population, Their Identification as Sexual Minority, Mental Health and Experienced Minority Stress’, BMC Public Health 22 (2022). https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-14198-2 we are not a small group. And photography has its role to play. Remember the AI-generated images of Geert Wilders? Or the already historic image of Trump’s raised fist after a failed assassination attack? Or, more on topic, the portrait of Roy Cohn, the raging homophobic prosecutor, by Mary Ellen Mark just before his death due to AIDS-related complications? It’s a haunting image, of a man living in his own violent delusion. As subtle and soft as Gonzalez-Torres was to bring the topic of homosexuality to the public sphere, Cohn spoke hatred in silence.

On the other side stands Gisèle Pelicot, the French woman who, after suffering nearly a decade of drug-induced sexual assaults at the hands of her husband, bravely waivered her anonymity to become a powerful advocate against sexual violence. With her iconic bob cut and oversized round sunglasses, she emerged as a symbol of liberation—a relentless force that shattered the silence surrounding domestic and sexual abuse. Pelicot is largely portrayed as powerful, unwavering, and self-secure. At a time when imagery is increasingly hijacked by right-wing narratives, we desperately need more figures like her. Reich also initiated a tentative step in the right direction, yet he remained somewhat restrained by the prevailing zeitgeist, limiting his perception of sexual liberation to only a fraction of its multifaceted dimensions.

Dimensions we have only begun to understand.

And yet, we still need Reich. We need a new revolution, if we can see Reich’s energy box for what it really is, a hopeful and naive promise for progress. What Reich dared to say almost a century ago continues to echo over the decades and needs amplifying today. His work was a daring exploration of the intersection between body, psyche, and societal norms – a vision that continues to resonate as we grapple with new forms of oppression. As the yagé doctor says to Eugene, Lee’s lover, in one of the final scenes of Queer, ‘What are you so afraid of? Hmm? Door’s already open. Can’t close it now. All you can do is look away. But why would you?’Guadagnino, Luca, dir. ‘Queer’. 2025, Berlin, DE: A24.

We have the photographs to prove it.