I 've been working on them for three years now. I started by washing, sanding, and painting them. They’re almost always white. They are the pillars of these places. Their condition will depend on visitors’ appreciation. As a scenographer, I find it impossible to ignore them. They must always be perfect.

Walls.

Rules and standards

Whether in foundations, museums, or galleries, immaculate white walls almost always accommodate works of art in the same way.

Since the twentieth century, the preparation of exhibition rooms for the public display of works of art has been shaped by rules that have become standards.

The first standard is the concept of creating an empty space.

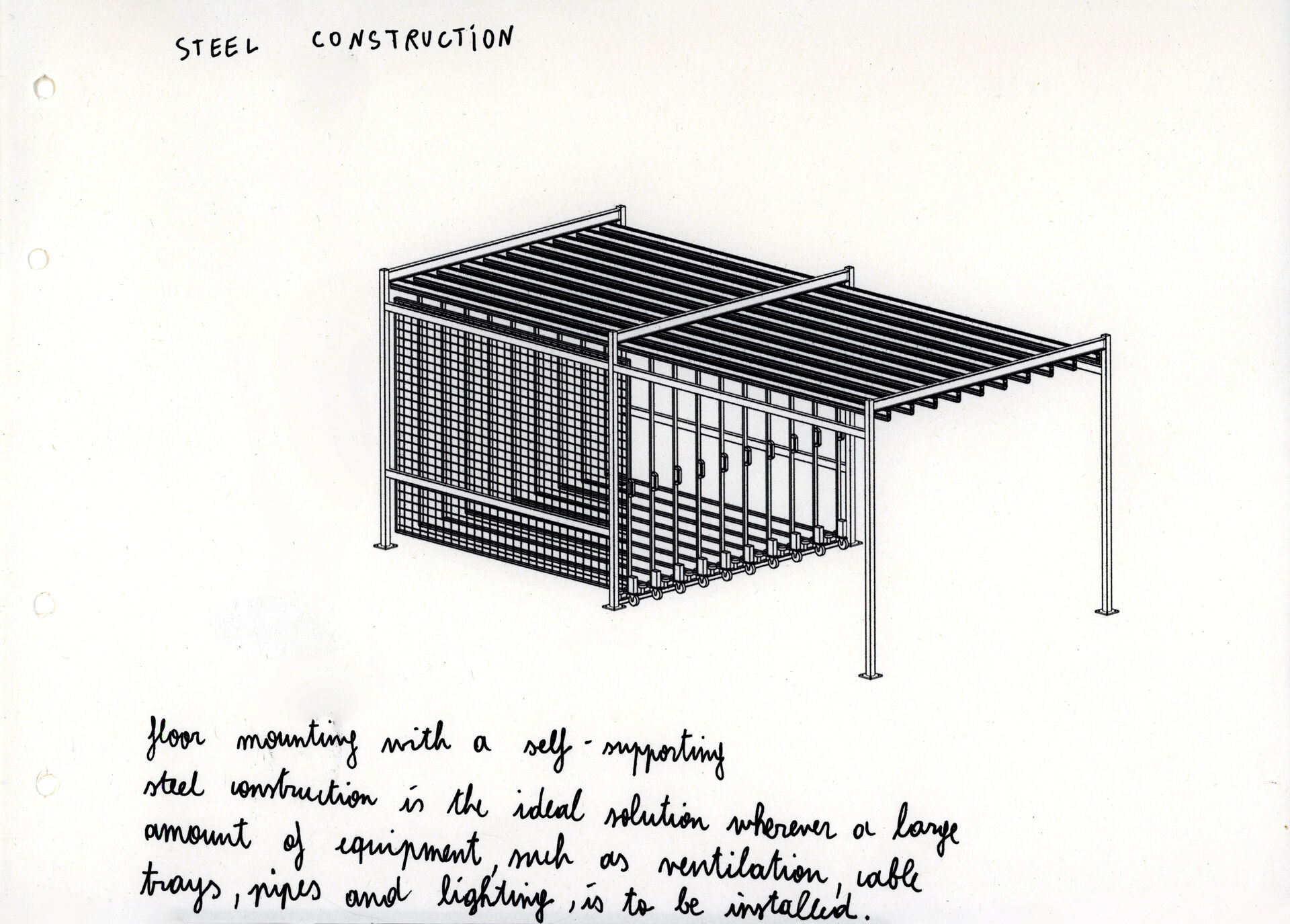

The second is the circulation of air, the control of humidity, and the maintenance of a stable and adequate temperature for the preservation and conservation of the artworks.

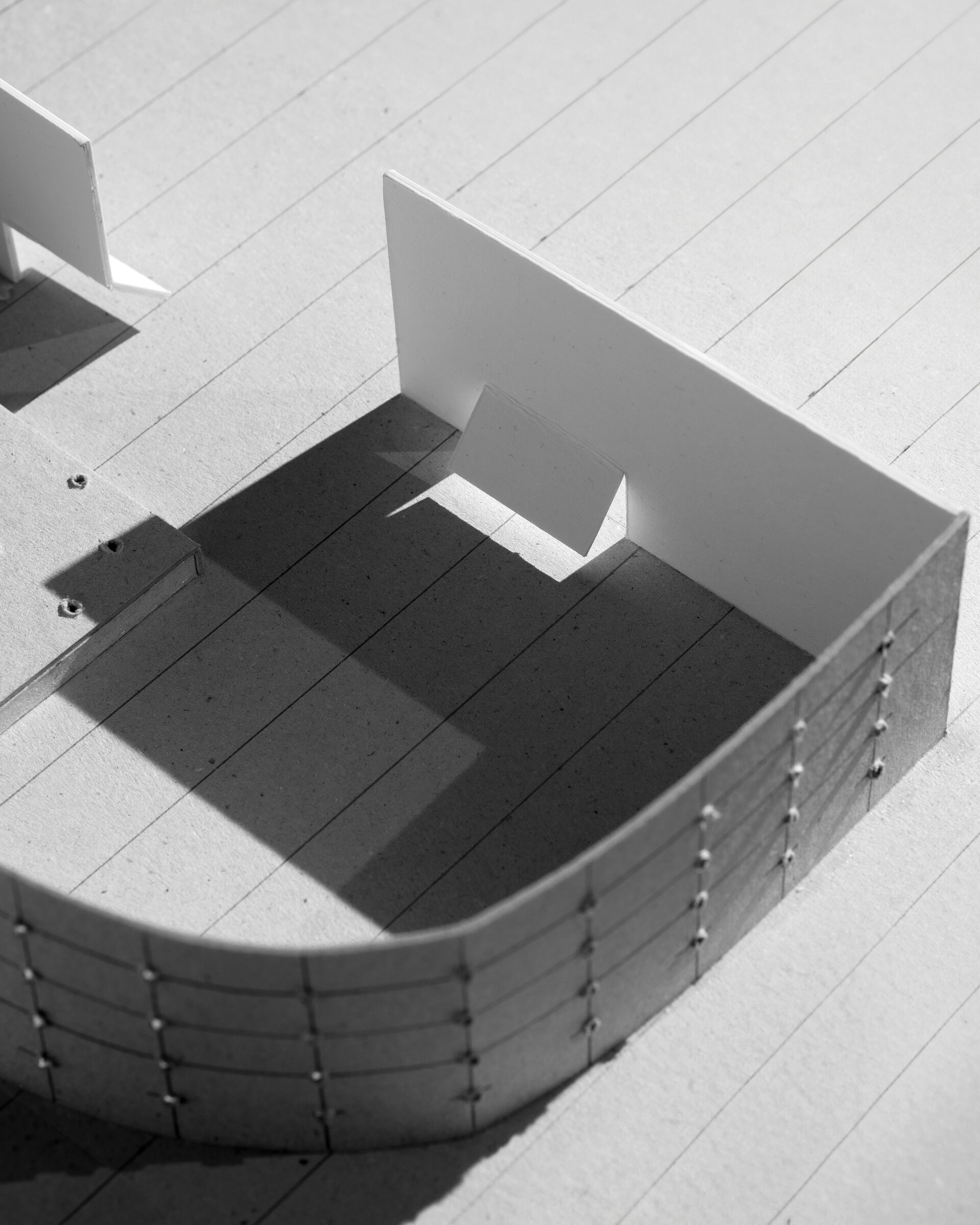

A gallery ceiling in Brussels

The third one is the millimetric adjustment of (artificial) light intensity to prevent any alteration of the objects on display, and to give them enough brightness to be seen.

This is all done in total invisibility. By this, I mean that these devices are often so concealed that they’re invisible to visitors.

In addition to these technical measures, equipment is required for the installation of the works due to their specific material constraints: the choice of materials for the walls on which to hang the paintings, electrical outlets on the floor, devices for attaching lighting equipment, etc.

The most crucial aspect of showroom preparation concerns the atmosphere, which is created by covering the walls with white paint to ensure good light diffusion. Floors, however, are generally not painted white because of the shimmering effect produced by zenithal light. Ceilings are often painted white for similar reasons of light diffusion.

Together, these operations help to create an atmosphere conducive to the presentation of works of art.

The stage is ready for the star.

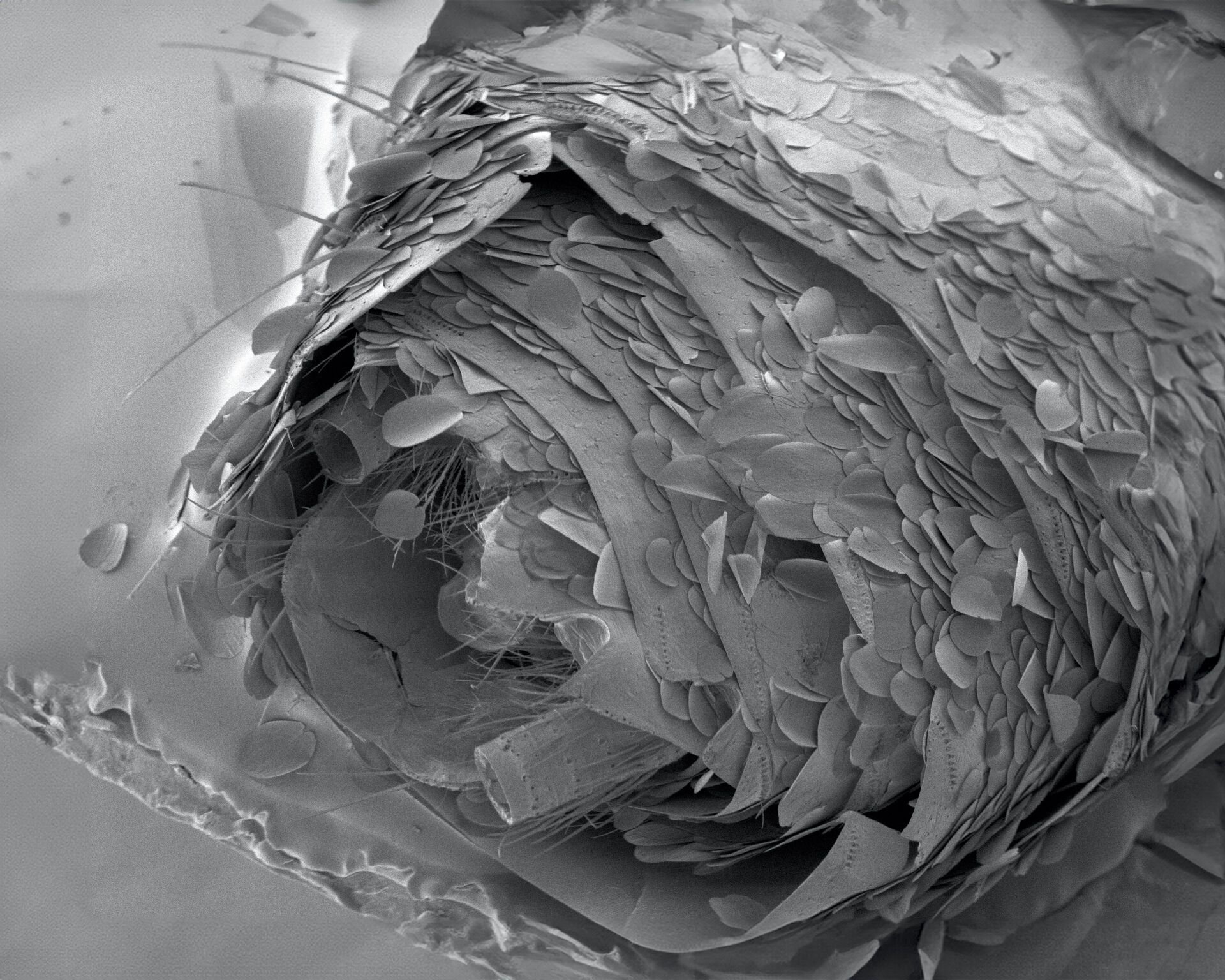

Inside view of paper structures in art crates

The combination of these two climatological and atmospheric aspects establishes conventions and standards for showroom preparation. Although variations are possible, particularly in wall colour, as long as they don’t contradict the fundamental principles of room preparation, this diversity is generally accepted.

The term ‘white cube’ is used by art critics and theorists as a general term for public exhibition halls. The white cube thus needs an abstract geometric model and a wandering gaze.

Art theorist, critic, and artist Brian O’Doherty emphasizes the parallel between the evolution of the works’ forms and their presentation.Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (Los Angeles: University of California Press San Francisco, 1999). This reciprocal relationship is based on speculative approaches associated with certain avant-garde painting practices. The white surfaces of the walls are thus an extension of the surfaces of the paintings. A passage from the second to the third dimension.

A second important point made by O’Doherty is the change in the status of art, now considered autonomous and singular in the period of ‘high modernism’. In other words, the white cube has become a standard – an independent, geometrically perfect space for works that stimulates observation, wandering and attention.

Does the white cube represent the place where every artist’s project must end?

Does an artist have to pass through the studio stage and finish his work in a white space?

Enter the silverfish

With this research idea in mind, I came across a small black mark on the frame of a painting freshly arrived from a Los Angeles studio while opening a shipping box in a Brussels gallery. My manager came running, thinking it was a silverfish.

A week later, I came across an article on ARTnews. During the summer of 2020, two silverfish were spotted on a print by Bernd and Hilla Becher in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in Iran.

Fear. Scandal.

The museum closed its doors for a limited time to sanitize parts of the building to prevent proliferation of the insects and damage to the artworks, and thus to preserve their treasure. BBC Persian posted this video on Instagram showing the two insects inside the frame in question. A huge sensation, the video racked up over a million views in just a few hours.

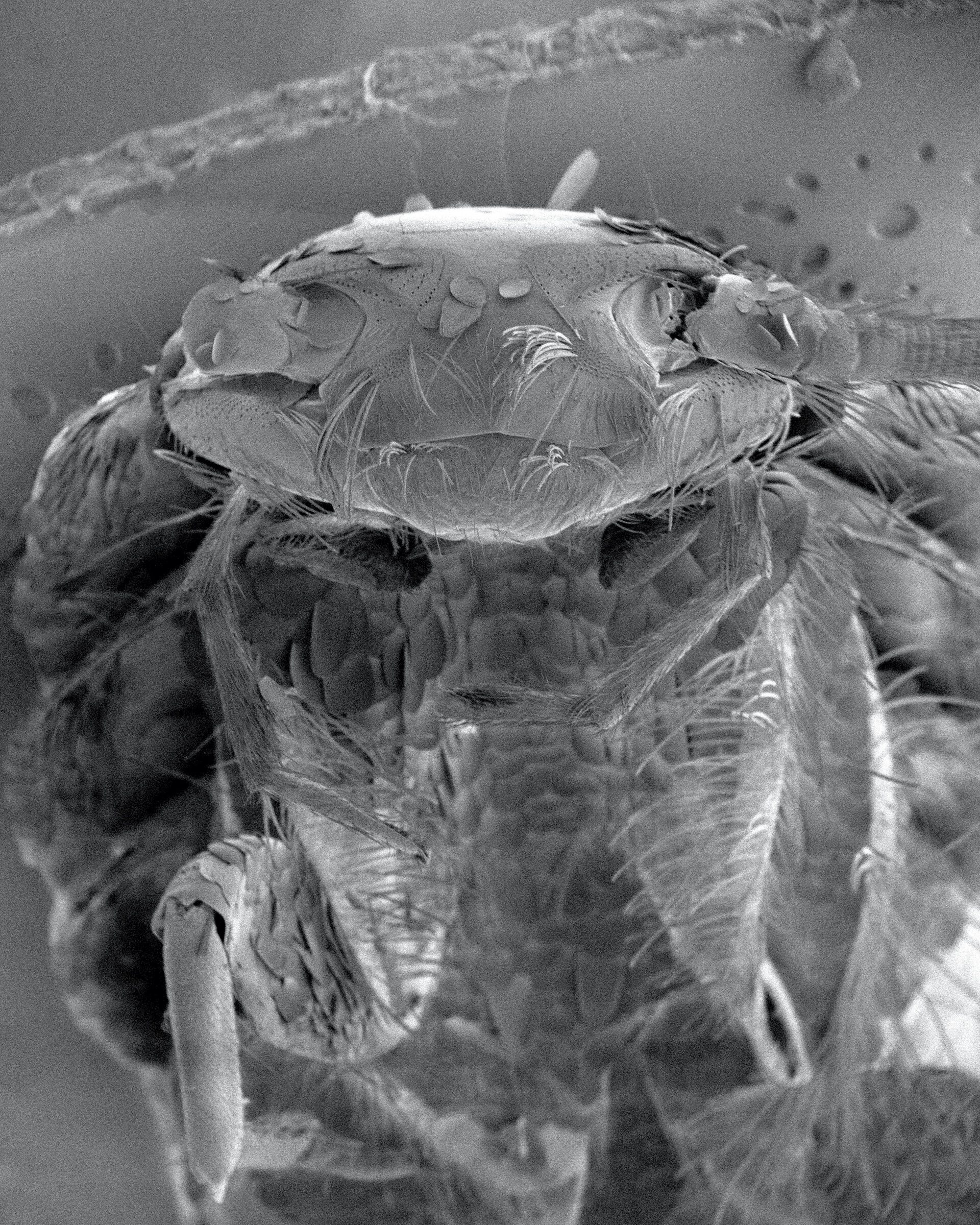

Thus, the silverfish seemed like the perfect living being, representing both the one who wanted to be at the shows and the one nobody wanted to see.

Thus, the silverfish seemed like the perfect living being, representing both the one who wanted to be at the shows and the one nobody wanted to see.

The notion of the white cube is obviously human invented, but above all it is disconnected from any kind of natural environment. Certainly, the works exhibited can take us on a journey to another world, but everything presented in such a space is scrupulously analyzed to ensure that the works are not damaged or improperly stored and displayed.

The environment is under control, and an error is not acceptable.

The silverfish, a small insect that appeared over 400 million years ago, was introduced into human spaces by the transportation of merchandise. Since then, it has become enemy number one in conservation and exhibition spaces, thanks to its diet based in part on paper, a material abundant in works of art. It is, therefore, a potential threat to works of art.

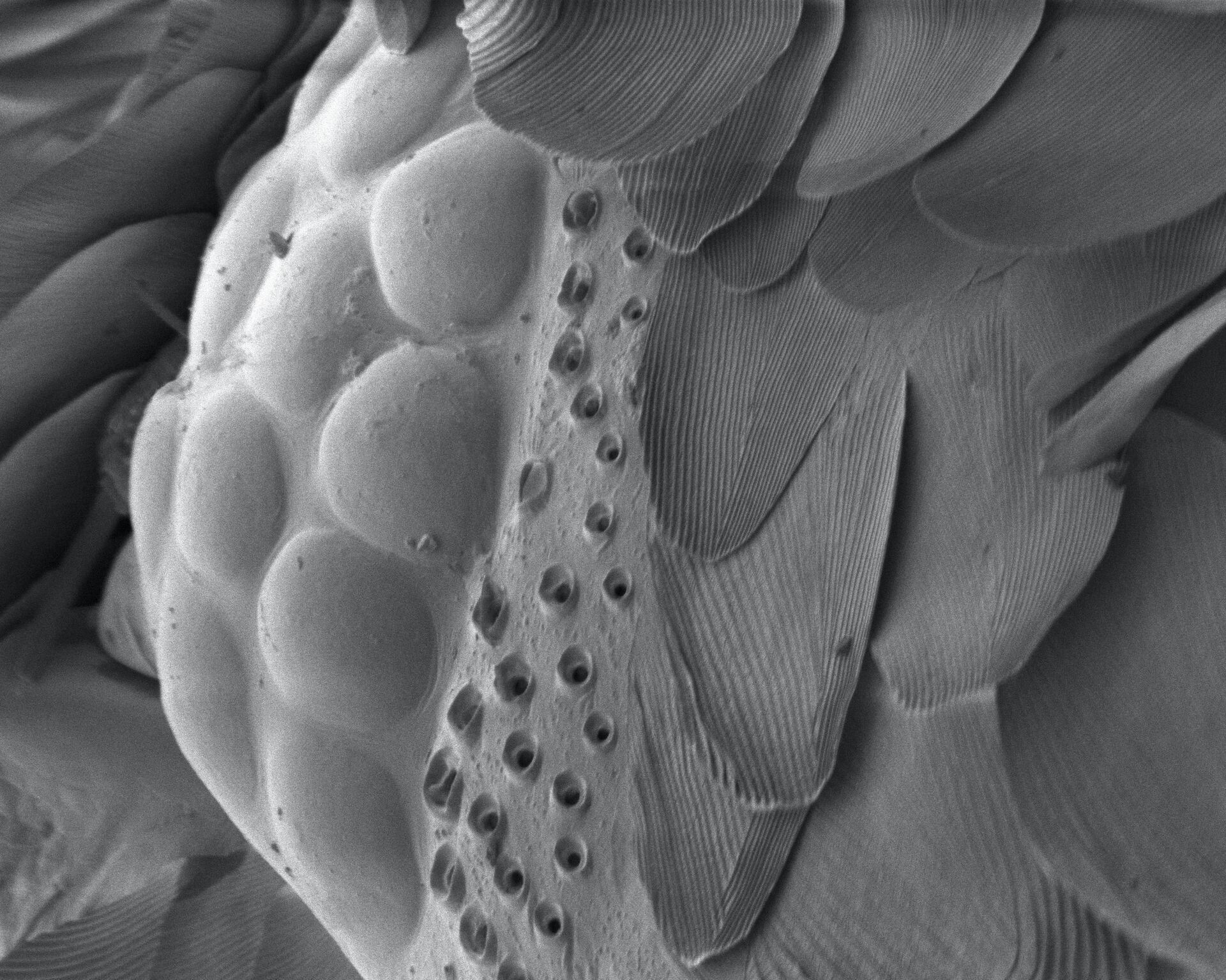

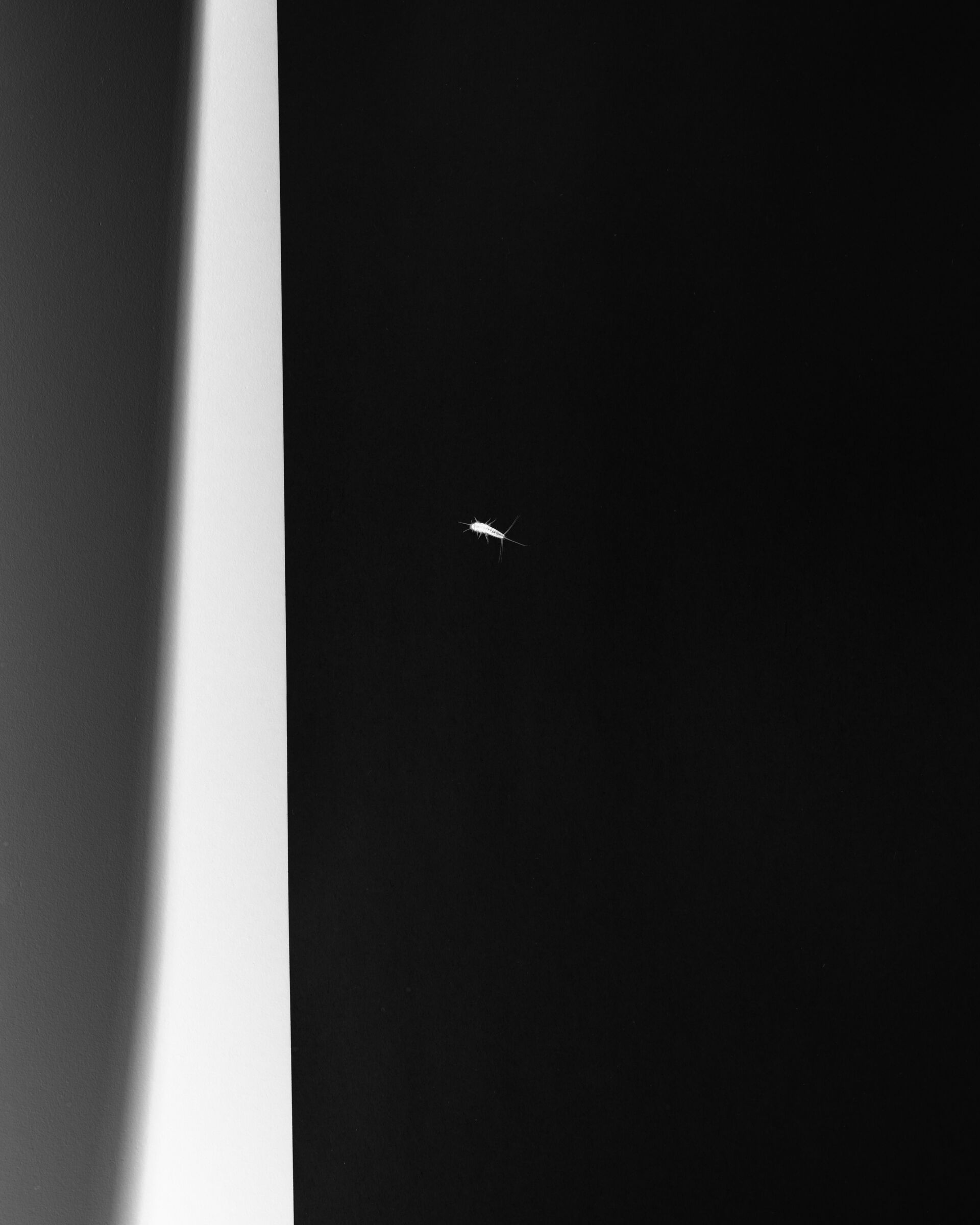

Infrared picture of a silverfish

The silverfish wants to be in the white cube, but the white cube doesn’t want it.

Would it be possible to learn more, to dialogue with this prehistoric insect that perhaps has something to tell us?

And so my studio became a laboratory, a place conducive to dialogue with this being.

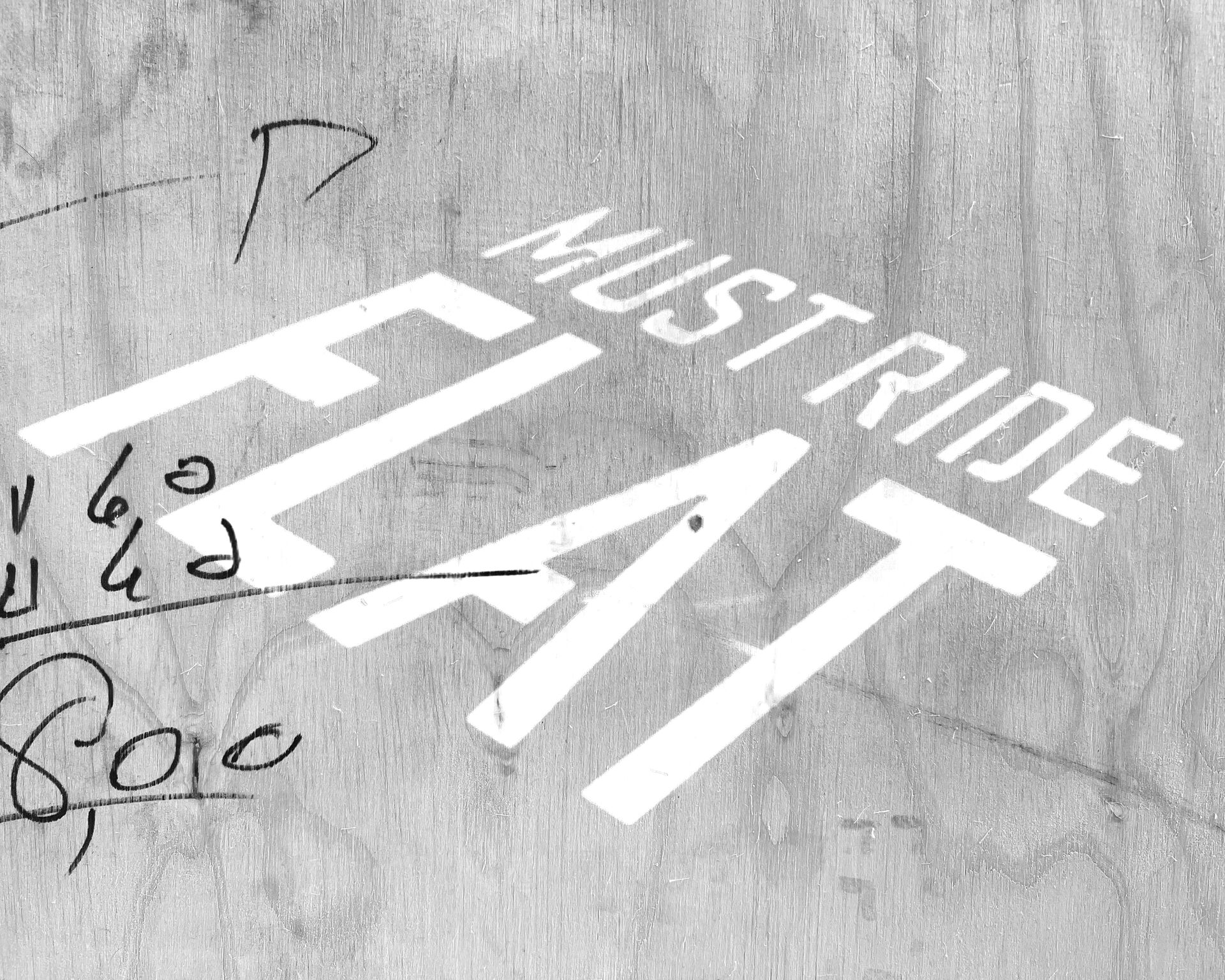

I began to collect various boxes used to transport works of art over kilometres to artists’ studios and galleries. I recycle and hijack them. These boxes are no longer fortresses for artworks, but places where silverfish are invited to live, reproduce, and feed on the same paper from which they have strayed. The paper is there, for them.

But how can visitors share this decomposition, this infiltration? How can the exhibition be part of a cycle of birth, life, and death rather than eternal life?

I consider that the notion of the exhibition is thus a discourse, to give to see to make understand, to make things appear. Another notion is of visualisation, as a process of visually representing a phenomenon or a set of data.

Parasitic photography

Since its creation, photography has never ceased to inspire and capture the real world, a world that no longer exists after the photo has been taken. In fact, there’s nothing more effective than images we never forget. Nothing exerts more power over us than what compels us to pay attention. Anything we pay attention to despite ourselves inevitably has an effect on us.

Whether true or not, we can be seduced by a photograph; whether the story is true or not, the boundary between document and fiction can sometimes be almost nonexistent.

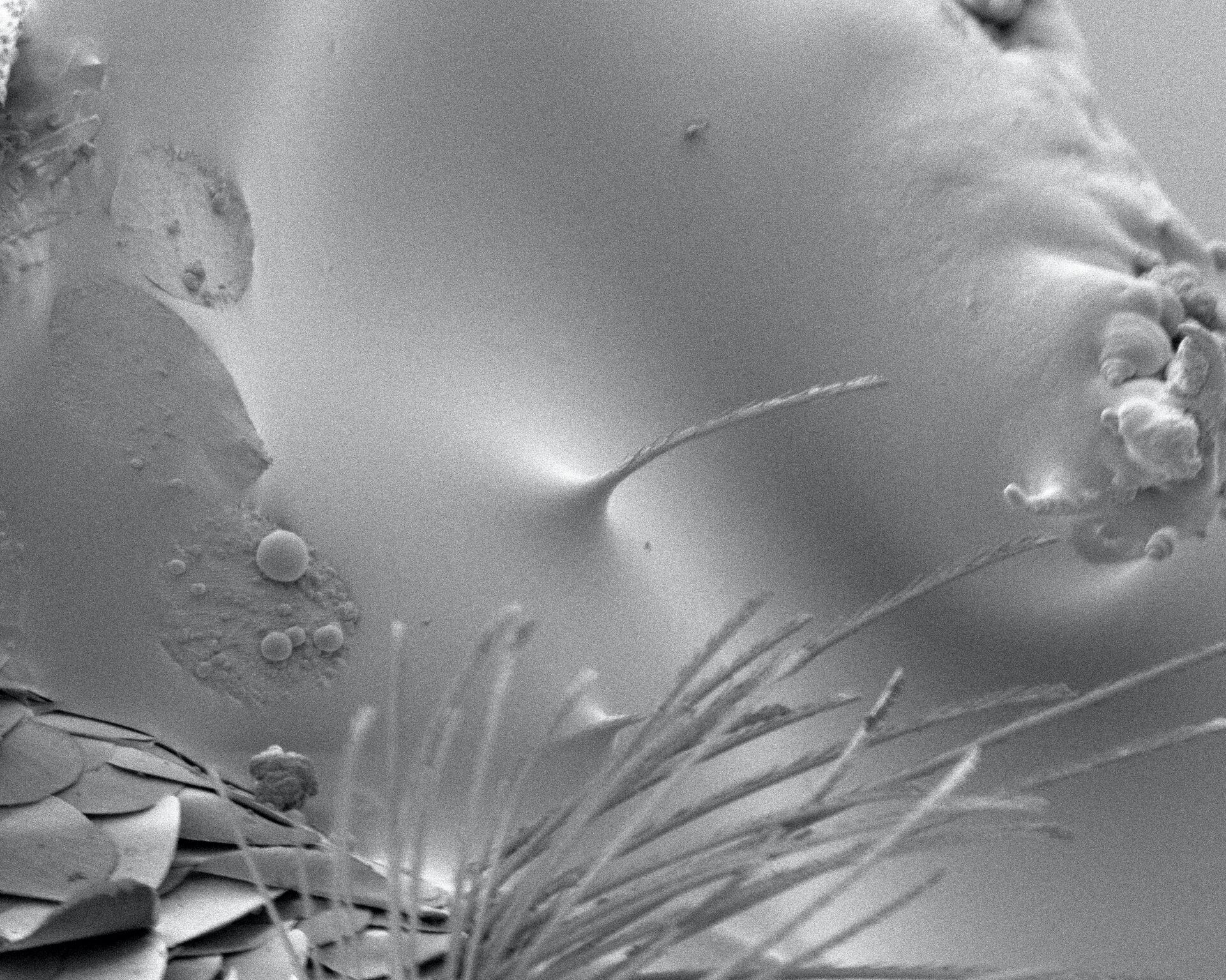

I use photography to deconstruct the notion of the presence of this ‘harmful’ insect via the infrared cameras in the transport boxes. This insect is generally active at night, as it doesn’t like light. In this way, I work on different infestations of boxes with cameras present in these boxes.

A second aspect is my collaboration with the Technical University of Delft, where I work with an engineer to visualize the insect via a scanning microscope, giving a completely different perspective to human vision.

Isn’t this what images are capable of offering us: different perspectives on the world, enabling us to see it differently?

The exhibition thus becomes a place of proliferation, where decomposition is invited, where the visitor is no longer faced with something stable in time but instead something in perpetual change. A place where photographic frames are no longer ‘barriers’ but ‘entrances’.

In this way, the exhibition becomes an invitation for the visitor to see, and to see themself looking at a change made available to them.

The silverfish is back in its environment.

The frames are unframed.

The stage is ready for the artist.