The Reliable Image

Impact and Contemporary Documentary Photography

It started with a shoe. In June 2017, Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Fund uploaded a long video outlining the supposed corruption of Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev to their website and YouTubeThis video was uploaded to multiple websites in order to secure a large and uninterrupted circulation. The video is called Он вам не Димон (Don’t Call him Dimon) and can be viewed here: https://dimon.navalny.com/ (figures 1 and 2). The probe of the Anti-Corruption Fund originated in the release by hackers of the underwhelming contents of Medvedev’s mobile telephone. No incriminating material was found; instead, the phone contained a plethora of mundane images showing the politician going about his daily routine. An informal photo of the PM sporting a colourful shirt, a large watch and fancy trainers, however, caught the attention of Navalny’s team as a possible inroad to a larger investigation. The visual detectives simply asked which credit card was used to buy these items. This unremarkable image served as the starting point for research that uncovered a large and widespread network of illegal transactions, false identities, questionable real-estate holdings and financial cover-ups that incriminated many high-ranking officials and businessmen. Navalny’s resulting video helped spark anti-Medvedev protests that caught Russia’s ruling classes off guard. Never before has such an unassuming image had such a large impact: it doesn’t pretend to be an aesthetic representation of an exceptional situation, and it doesn’t maintain a privileged relationship to truth, like previous forms of documentary photography. Medvedev’s holiday snap illustrates a new paradigm in documentary photography in which aesthetics, truth and artistry are replaced by reliability.

Wilco Versteeg

05 nov. 2019 • 10 min

Paradigm shift

Traditional documentary photography is undeniably in crisis. The most important documentary images of the twenty-first century have not been made by documentary photographers per se. Visuals of important events are provided by civilians who happen to pass by; victims of human rights abuses are increasingly able to document their own plights; and activist groups have branched out into documentation through photographic imagery to make their cases in courts and public forums. Meanwhile, traditional documentary photography seems to have found a safe harbour in cultural institutions, gallery spaces or in the service of NGOs, but in doing so it has retreated from the public forums in which it most logically serves its informative societal function. This retreat is exemplified by commemorative exhibitions and ‘the photobook’ as the preferred locus of state-of-the-art discussions on what heretofore used to be a public, diverse documentary culture.For a dissection of contemporary documentary culture, see Roberts, John. 2009. ‘Photography after the Photograph: Event, Archive, and the Non-Symbolic’. Oxford Art Journal 32, no.2; and Brunet, François. 2017. La photographie: Histoire et contre-histoire, Paris : PUF. This self-sequestration might be the logical result of a medium that has struggled to remain relevant in our political culture and might slip further into artistic niches if it continues to turn a blind eye to the documentary demands of our sceptical, digitising epoch.See Versteeg, Wilco. 2018. The Reliable Image. Documenting Contemporary Warfare with Photography, Paris Diderot (unpublished); and ‘Fotografie als bewijslast in tijden van ongeloof’. rekto:verso 7 August, 2015.

Screenshot from ‘Don’t’ Call him “Dimon”’

Screenshot from ‘Don’t Call him “Dimon”’. The text read ‘How Medvedev’s trainers prove to be his downfall’.

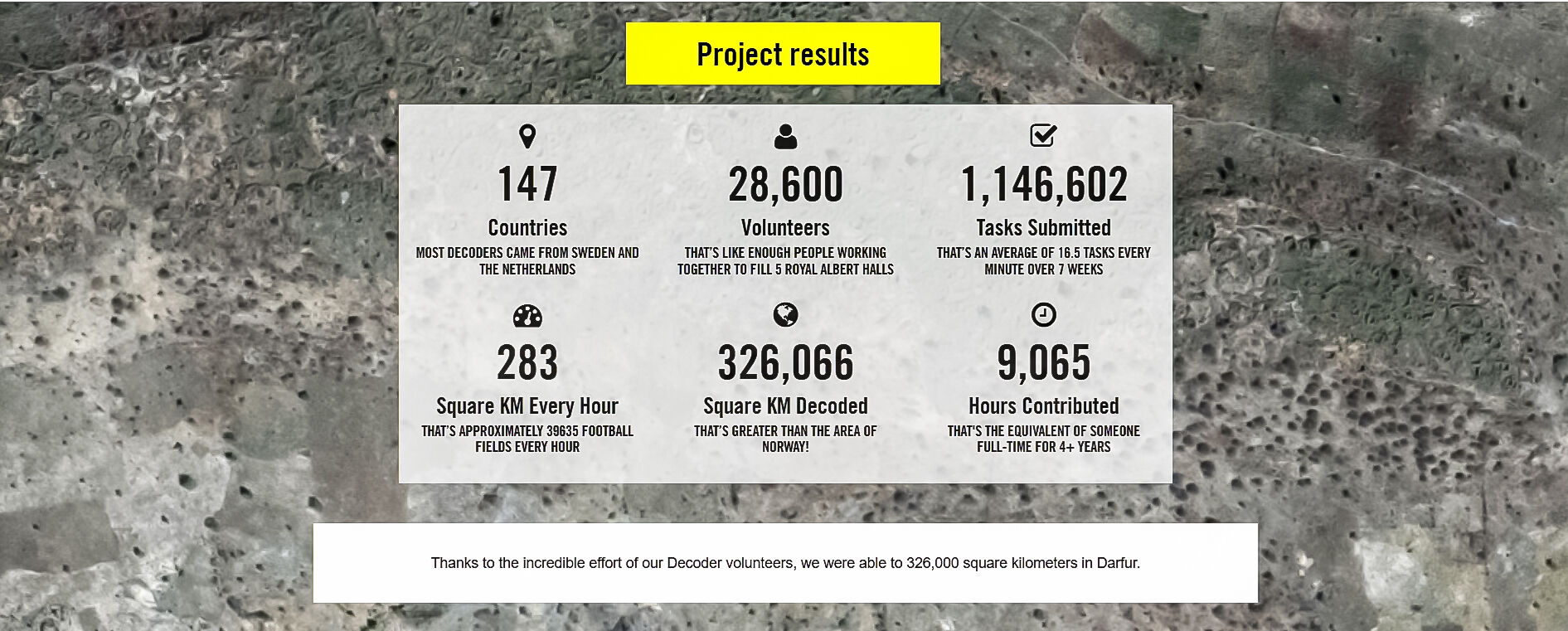

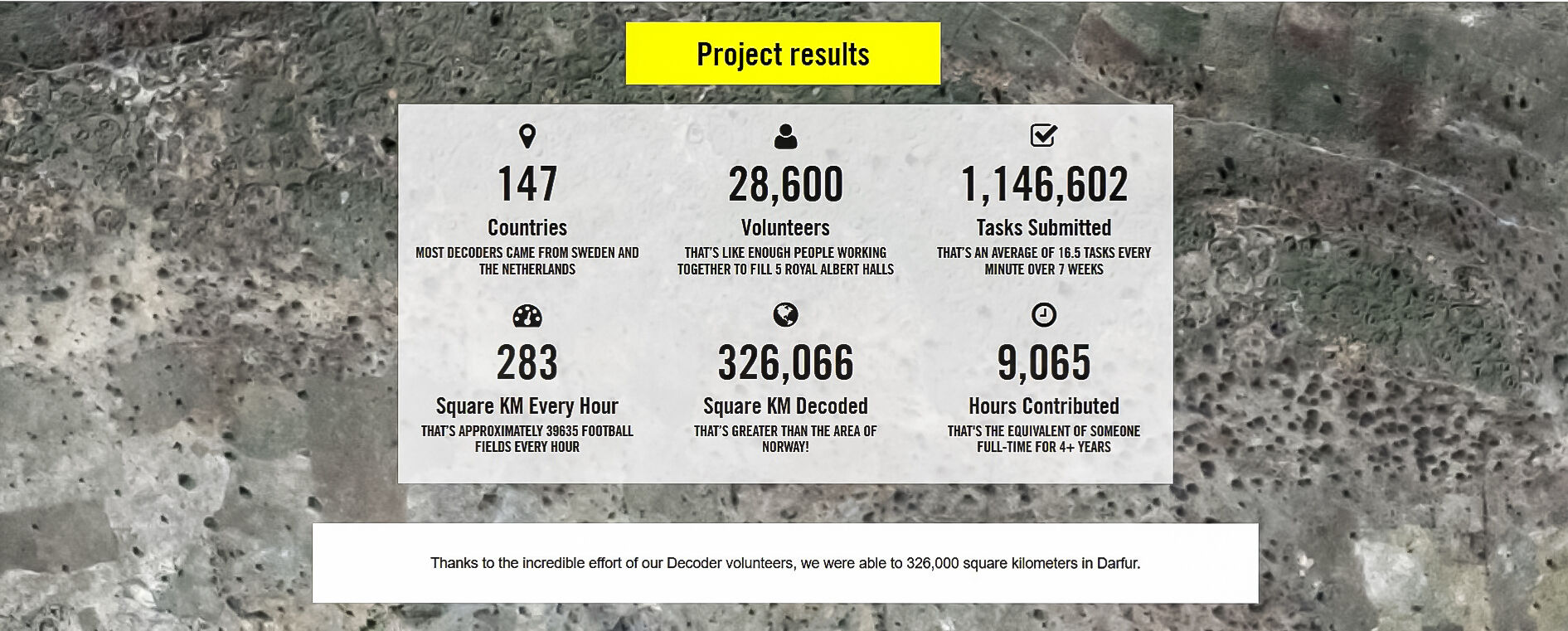

Screenshot Amnesty International’s Decode Darfur website

Screenshot Amnesty International’s Decode Darfur website

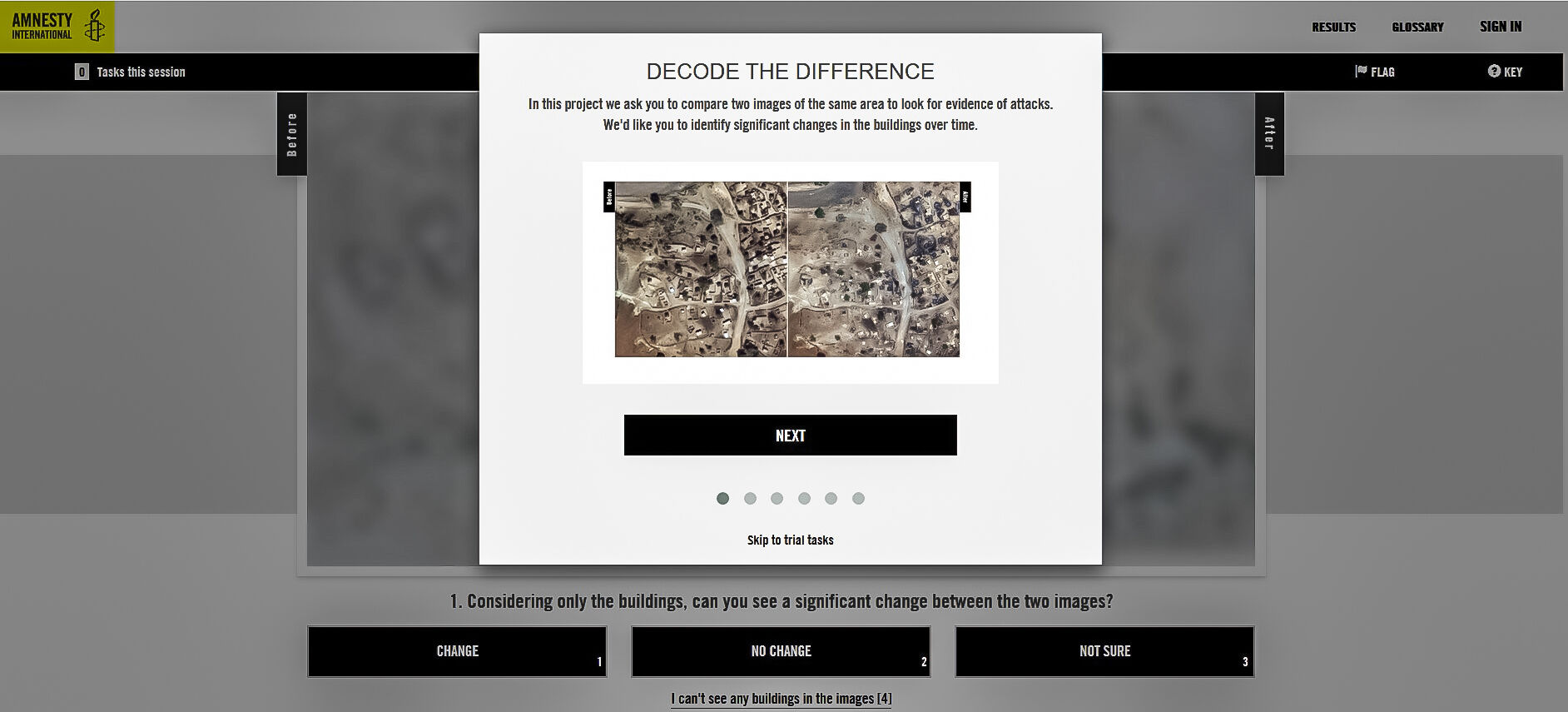

Screenshot Amnesty International’s Decode Darfur website

Screenshot Amnesty International’s Decode Darfur website

Screenshot NOS newsbroadcast showing a BUK missile-lancer with digital overlay

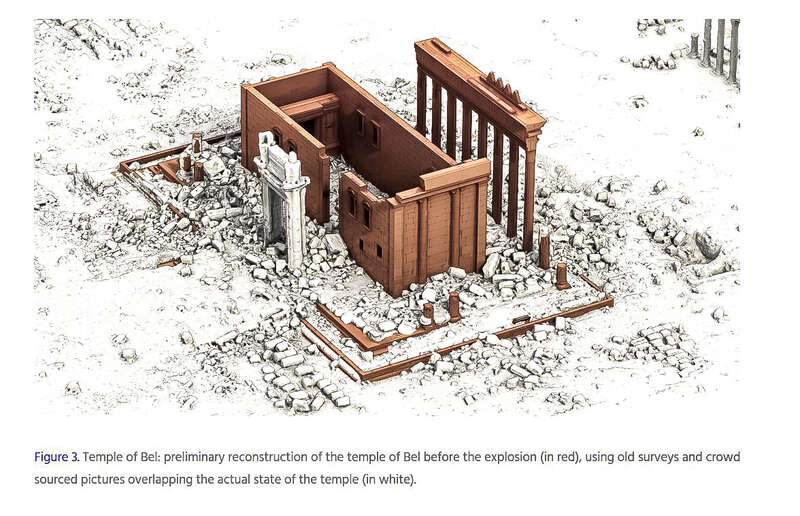

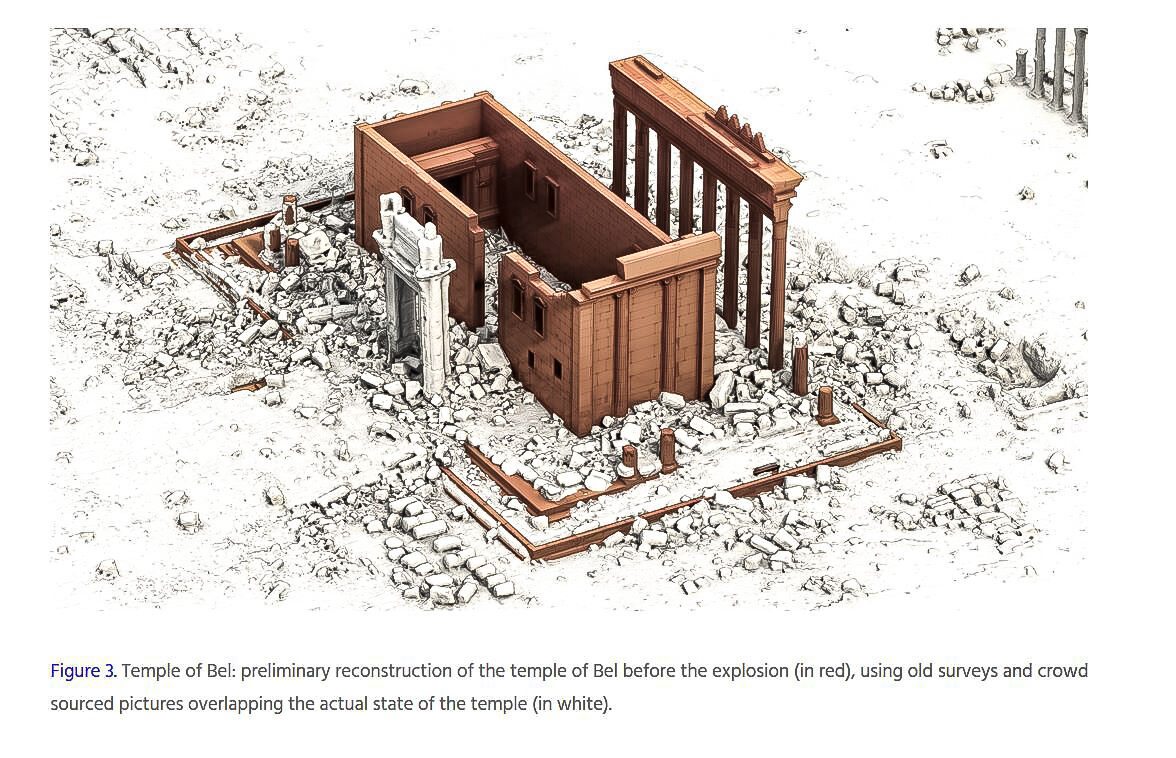

Screenshot Iconem visual reconstruction of the Temple of Bel, using archival footage as well as digital models

What are these demands, and how can documentary photography, in all its diversity, continue to impact society? This article proposes a paradigm that safeguards documentary photography from the trappings of scepticism, irrelevance and political obscurity by seeking to cut it loose from the millstone that has been hanging from its neck for almost a century: the insistence on its privileged relationship with the truth and, having been discouraged by relativistic theories, with its equally deceptive claim of raising awareness as the nec plus ultra of a medium that can be much more. By freeing documentary photography from the demand to tell the truth, we do more justice to the early history of the medium—in which photography was instrumental in science and other pursuits of knowledge—and create a future in which it can play a role of political importance. To do this, we might have to accept photography’s subordinate place in larger constructions of evidence. This article is a call to rethink the medium through the concept of reliability. In our sceptical day and age, claims to the truth are outdated; the reliability of an image within a clearly defined context is more important. In fact, these practices have deep roots in the history of the medium: late nineteenth and early twentieth century science and police photography never considered the medium the alpha and omega but always as a tool to achieve clearly defined goals. While these histories are often overlooked or considered as mere stepping stones in the medium’s progress to artistic, self-referential maturity, they show an awareness of the limits of the medium and use these limits to construct reliable narratives based on facts instead of affects, emotions, aesthetics or the author’s ex cathedra exclamations of his or her own work.

Let’s do away with some perceived ideas of photography: most photographs do not circulate widely or, frankly, at all; even our most gripping images have close to zero impact on political and societal developments. The impact of photography can hardly be overestimated, but the impact of individual photographs is usually grossly overstated. This is most easily demonstrated by looking at war photography, the forum in which most state-of-the art discussions on documentary photography play out. The ideal that documentary photography reveals ‘everything’ and that its iconic images impact the hearts and minds of the people as well as actual policy is recent, originating from the Vietnam War. This so-called Uncensored War is repeatedly said to have been shortened if not outright ended because of a handful of iconic images. While this is an appealing discourse that serves as the ultimate apologia of a medium that’s suffered accusations of indecency and voyeurism, it simply isn’t true.This myth is persistent despite its debunking by, among others, Wyatt, Clarence. 1993. Paper Soldiers: The American Press and the Vietnam War; Chicago: University of Chicago Press and Griffin, Michael. 1999. ‘The Great War Photographs: Constructing Myths of History and Photojournalism’. In Picturing the Past: Media, History, and Photography, edited by Hanno Hardt & Bonnie Brennen. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. Even today, we wish that images such as that of a Syrian boy face-down on a Turkish beach can and do change the world we live in, but the harsher reality is that these images are seen and remembered merely as icons of photography’s failure to do more than depict reality. The hope that documentary photographs mobilize people proves to be as persistent as it is futile.

Exceptional forms of power

Considering recent technological developments, the story becomes more complex. Since the late 1980s, developments in automated and autonomous image-based technology have taken flight, especially outside the traditional realms of photography and its academic and critical study. Instead, the intersections of science, technological start-ups and state power have created more interesting developments in photography and image-making. Trevor Paglen is a notable exception. In an alarmist article for The New Inquiry,Paglen, Trevor. 2016. ‘Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)’. TheNew Inquiry, Dec., 2016.he asserted that images no longer need human agency to operate and cannot be understood within our current human-centred critical apparatus. Paglen states that ‘(a)ll computer vision systems produce mathematical abstractions from the images they’re analyzing, and the qualities of those abstractions are guided by the kind of metadata the algorithm is trying to read.’. This leads to a reversal in which, according to Paglen, ‘(w)e no longer look at images—images look at us. They no longer simply represent things, but actively intervene in everyday life.’ Paglen sees this as a threat and says that ‘we must begin to understand these changes if we are to challenge the exceptional forms of power flowing through the invisible visual culture that we find ourselves enmeshed within.’ These developments include Chinese face-recognition programmes that autonomously attribute value to certain behaviours, billboards that track our eye movement and change messages depending on our personal histories and unmanned killer drones that act when patterns on the ground indicate hostility. Paglen’s article is a call to arms to update our perceived ideas on visual culture in this volatile technological reality.

A decisive date in the history of our visual culture and an early example of this autonomisation of images is 3 July 1988. On this date, the United States Navy Cruiser USS Vincennes shot down Iran Air Flight 655, killing all 290 passengers on board. A tragic mistake for which President Ronald Reagan immediately apologised, this incident is rooted in the deceptive power of images. The cruiser’s onboard computers misidentified the commercial plane as a fighter jet and autonomously set in motion its pre-programmed response to imminent threats. While human supervision over this automated process yielded substantial doubts as to the supposed belligerent identity of the aircraft, the chain of command chose to ignore their own observations and instincts, instead trusting ‘what the computer was telling them.’Singer, Peter W. 2009. Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century. 125. London: Penguin Press.

While Paglen is right to worry, warn and wake us from our complacency, we should equally guard against technological determinism, which is nothing more than a facile offshoot of the economical determinism that’s chased academic photo theory to the brink of irrelevance and has harmed the diversity of political expression in the artistic and academic worlds. While it’s true that technological developments give states and other powerful parties new and different means of control, many of these are or will become available to the public at large even if often used in a mundane way. In this paradigm, the technologies and networks of the powerful can be used by those who wish to protest, as a great judo player will use the power of her opponent to bring him to his knees.

A telling example is provided by satellite photography. Technology from the Cold War, in which satellites served to control and intimidate the enemy, is now within easy reach of non-state organisations and, through Google Earth, to civilians. For example, a PhD student using imagery from Google Earth proved that the U.S. prison at Guantanamo, Cuba, expanded between April 2003 and February 2008, thus providing the first overview of the complex itself and also belying statements that the facility was slowly closing. The student downloaded hi-resolution images that enabled him to interpret their details and compare them to and corroborate them with other sources, such as leaked government reports on the hermetically sealed prison.Pringle, Heather. 2010. ‘Google Earth Shows Clandestine Worlds’. Science 329, no.5995. Another high-profile satellite-based initiative is Amnesty International’s Sudan Project. The organisation invites public scrutiny of satellite images in order to investigate human rights violations in the Northeast African Count (figures 3, 4, 5). Notwithstanding a pixel cap for private satellites that prevents viewers from distinguishing details smaller than the average human being, the future use of this form of photography will further uncover what some want to remain hidden.

Other examples of documentary practices in which photography plays a role but isn’t the sole medium of expression can be found in the crowd-sourced investigative journalism of Bellingcat’s, most notably in its research on the MH17 airplane shot down over Ukraine in 2015. Or in Errol Morris’ book Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of PhotographyMorris, Errol. 2014. Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography. London: Penguin Press. , his deeply researched exploration and exposure of the myths of photography, using recent technologies to criticise easy assumptions about the truth value of photographs and asking what notions such as ‘staged’ or ‘fake’ mean in today’s digitised world. Another example is Iconem’s fascinating projects restoring war-torn patrimony in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan based on extant photo archives and digital image reconstructions (Figure 7).

From truth to reliability

These projects are carried out across the spectrum of science, journalism, humanitarian work, diplomacy and legal aid, and they illustrate a new paradigm in which reliability is more important than truth and aesthetics. Instead of playing on the unlimited power of images to tell stories, they try to limit its saying power by offsetting them with text, digital embellishments (Figure 6) and other forms of manipulation unacceptable to previous forms of documentary culture. Through these manipulations, which spell the de facto end of a pure documentary and journalistic aesthetic and ethic, photographic images can speak more clearly in the public forums in which current battles for reliable facts and worldviews are raging. In other words, should documentary photography want to remain relevant in today’s world, it should break out of the confines of artistic institutions, let go of its quasi-mythological poetics and redefine its role in a changing media landscape. This is a shift from photocentric to photo-inclusive, from truth to reliability and from art back to politics, and it’s the battle at the heart of twenty-first century documentary culture.