I detest photography, yet I take photographs incessantly. Ethnographic photography, ethnography and photography in general are inevitably forced to confront a liminal space fraught with ambivalent situations. Their inevitability resides in the historical and temporal frames that circumscribe the life and death of their subjects. Much has been written about photography and the vanishing present, the passage of a now into a then and the world’s refusal to be reduced into photographs, but much remains to be thought about the photographed lives still unfolding according to their own rhythms, which are vaguely suggested in the present. Neither the then nor the now necessarily determines a photograph.

***

In what follows, I will write about the photographs I took on a trip to Tapachula (Nov/Dec 2019), Mexico, also known as Prison City. It’s located in the state of Chiapas, which borders Guatemala, where thousands of migrants from Africa, Haiti, Cuba and South and Central America have been literally stranded on their way to the United States. In my writing, I refuse to come up with a totalizing ‘narrative’ about migrants who have different background and histories. In an attempt to keep the unfolding future as open and hopeful as possible, I’ve opted for a fragmented structure. During the process of editing the photographs, I’ve shared images with some of the migrants I met in Tapachula. Some expressed happiness at being part of my work. Others expressed hope that I bring their stories beyond their immediate situation in Tapachula. I often insisted that I’m only a visual artist, but they didn’t mind. They knew that I had access to institutions in Mexico and the United States. I received permission to photograph.

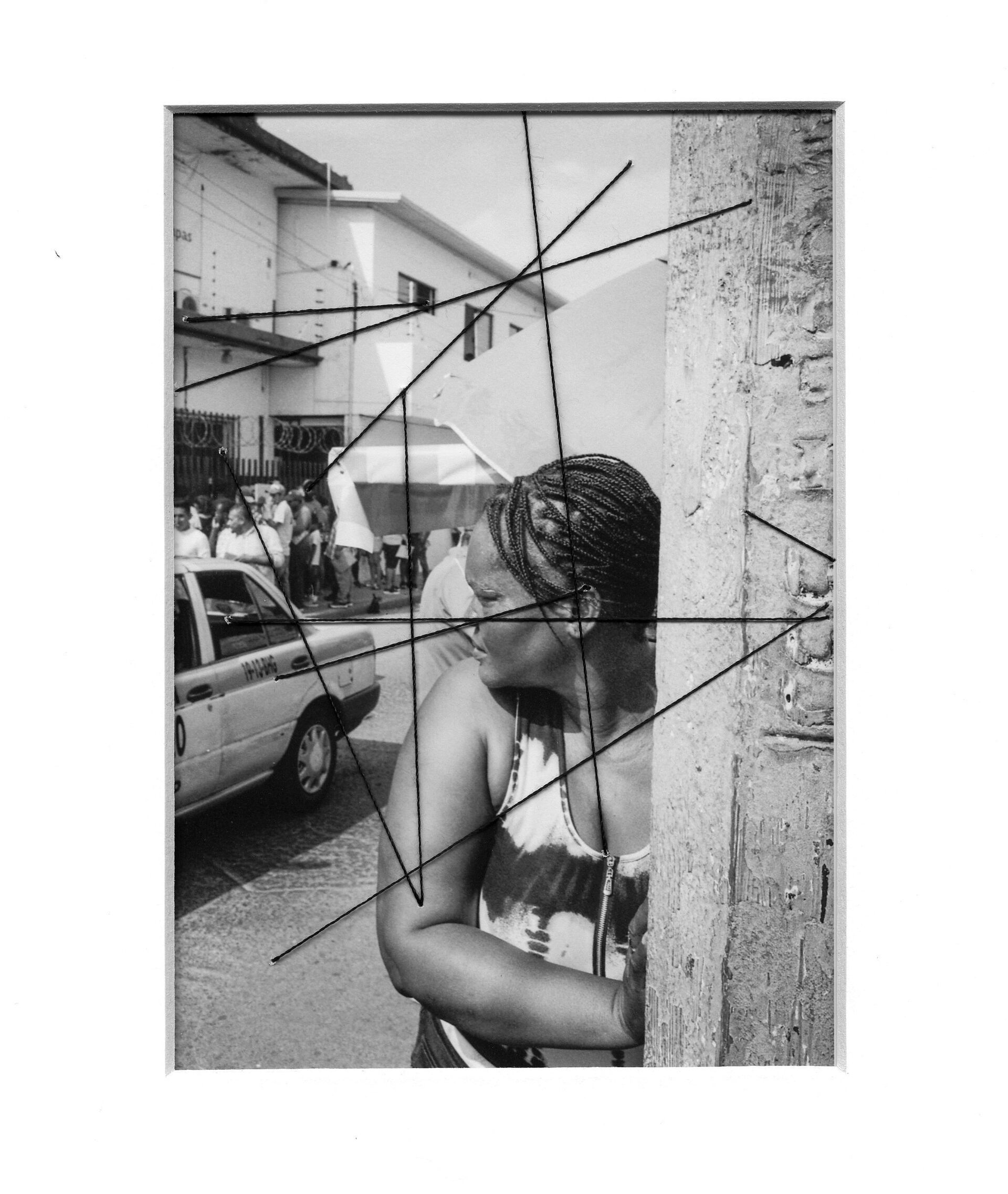

The photographs showed here were taken on film with a handheld analogue camera. After developing the negatives, I scanned them and printed them on Platine fibre rag. To share the photographs digitally, I matted and scanned them to imbue the images with a sense of materiality and accentuate their potential participation in our lives. As I will further elaborate in what follows, stitches, veils and paint on some of the images recompose the relationship between the viewer and the photograph. Altering these images complicates the transparency expected in ethnographic and documentary photography.

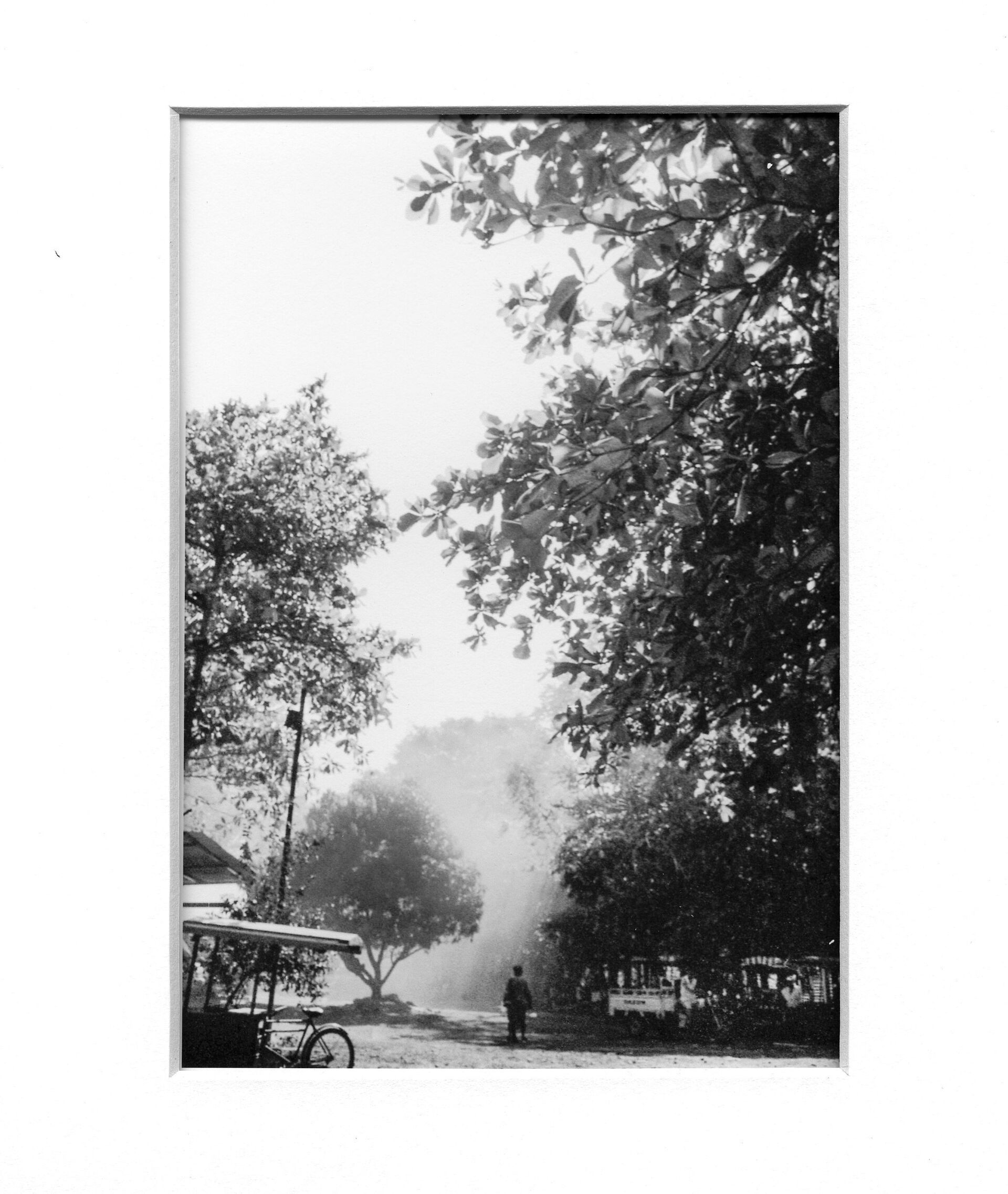

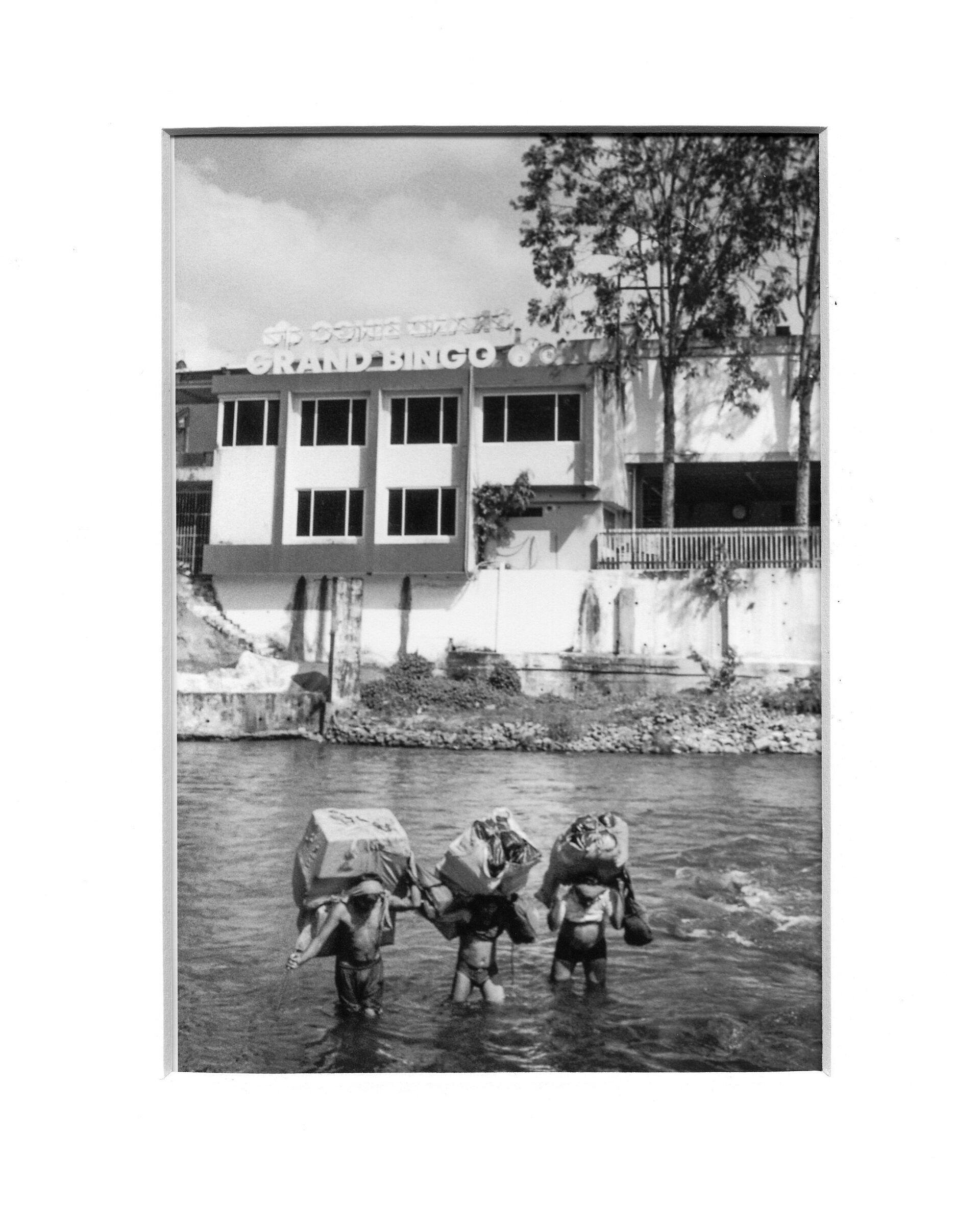

'Paso Limon', Informal Entry Port between Mexico/Guatemala.

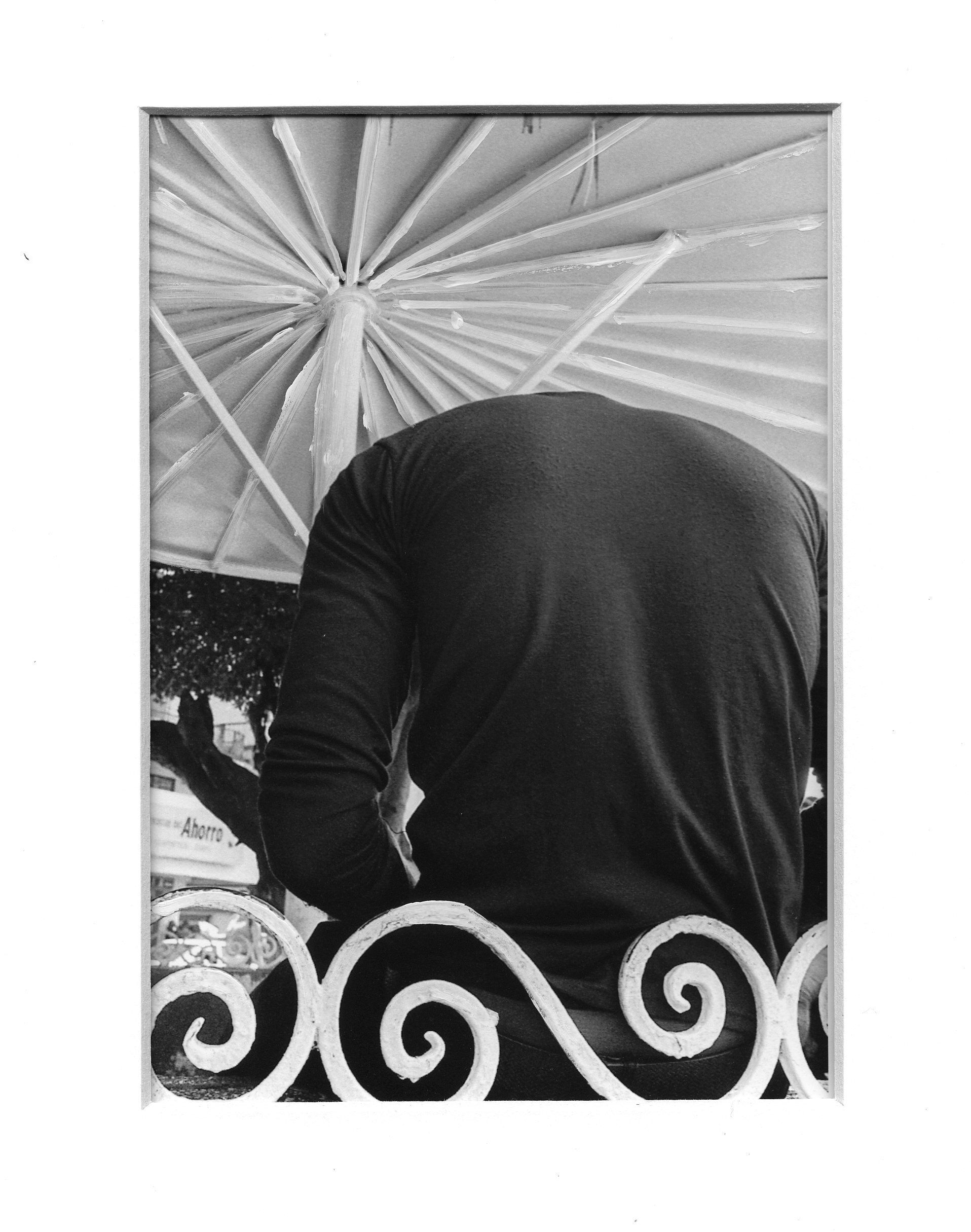

Resting under the Umbrella, Tapachula.

Ethnographic photography conveys what I call (drawing from Freud’s ‘Mourning and Melancholia’Sigmund Freud, ‘Mourning and Melancholia’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XIV, trans. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1914–1916), 243–58. ) a manic complex, a disabling melancholia turned into creative energy. This paradox is at the heart of what I think of as the manic complex in documentary and ethnographic photography, a deep melancholia turned into creative energy and rebellion. This manifestation of melancholy transforming into mania, however, has undersides that connect photography to colonialism; take, for instance, photographers who insist on photographing unwilling subjects, thereby inflicting wounds, or those whose photographs naturalise colonial regimes.

In my work, the urge to counter epistemic and imperial dominations often begins with a melancholia haunted by silence, uncertainty and anxiety. Melancholia, Freud stated in ‘Mourning and Melancholia’, acts like an open wound, drawing to itself cathectic energies from multiple contexts and directions. In my ethnographic work, I systematically traverse wounded places and streets in which people are devastated by psychological and physical violence. As I’ve immersed myself in the desolation, destitution and despondency of the precarious lives I engage in my photography, I’ve come to dwell on the strains of my own wounds. Dealing with these wounds, I find it important that my corresponding photographic endeavours aren’t absorbed into and incapacitated by the systematic recurrence of colonial dominance. I take mania to be a flight from historical determination in the likeness of lightning; it offers a counterpoint to the dominant imperial narratives.

***

The black-and-white analogue photos presented here – at times stitched, painted or veiled – with marks interrupting their spectrum, combine memory and prophecy, referencing both irretrievable pasts and anticipated, often unspeakable futures. The manic complex of photography consists not only of what’s to be seen and recorded by the camera but also what remains unsaid, outlawed or silenced. It’s through these spaces that photography makes its way, vexed by the fatigue brought of colonial hubris. And yet, it’s precisely these incapacitating conditions that lead to creativity. Indeed, photographs, with their mute immobility, have the power to break such social silences.

***

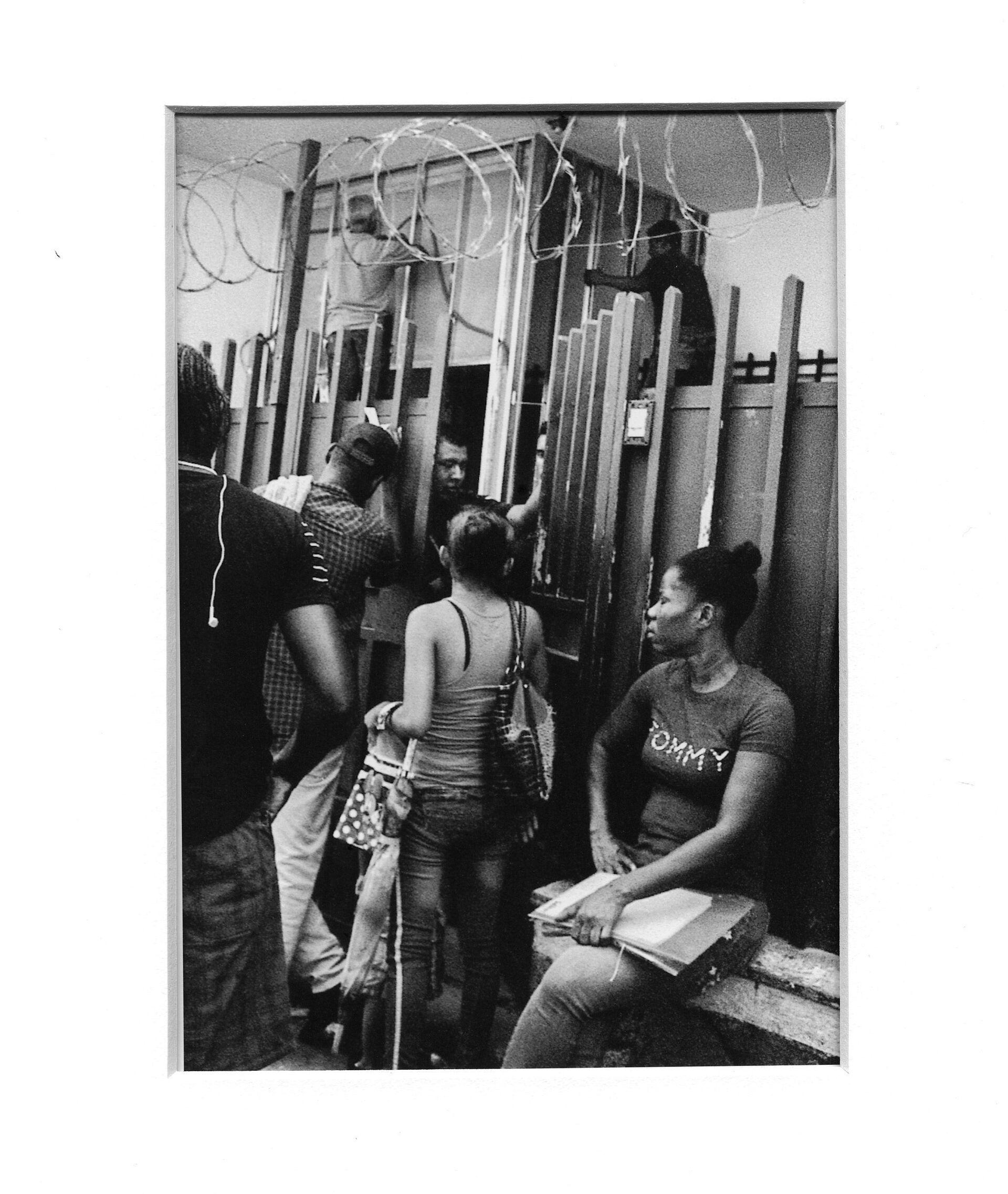

Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, #2, Tapachula.

Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, #3, Tapachula.

Whereas veils mediate spiritual and material worlds, stitches fragment and recompose the relationship between viewer and photograph. They mediate the viewer with the spectrum of the image warding off powers that seek to destroy life. Stitching and veiling emphasise wounds manifest in the bodies recorded by the camera that could otherwise go unperceived. They also seek to close the photograph to unintended understandings and misunderstandings. By stitching, painting and veiling, I materially intervene in the images I produce. Similar to broken dreams, these modified images reflect the limits of my relation to power institutions that seek to curtail flight. An image can always be read as both a testimony of what needs to be denounced and a reiteration of a larger evil construct. If an image refers to a set of possibilities and intentions latent within itself, interventions in it may counter the possibility that it can be subjected to opposite readings: for example, photographs of a lynching may at once be a source of pain to a community and of satisfaction to a White supremacist. The same image can be seen as both cure and poison in the tradition of a pharmakon: from remedy to poison, from denunciation of violence to satisfaction in regarding the pain of others. Photographs in which I haven’t intervened reveal the structural silences haunting migrants’ oppressive circumstances, the instability of the image and a dream world where the beauty of natural landscapes, solidarity and breaking bread rein free.

***

The series of analogue black-and-white images presented here stem from my work in Tapachula, the main point of entry in a journey to the U.S. border. At the time of my trip, Tapachula was known as Prison City because asylum seekers often remained there with no possibility of escaping or returning homes. Since then, conditions in Tapachula have been profoundly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, hence my reference to events in an inaccessible past. There, thousands of asylum seekers wait for documents that would enabled them to cross Mexico en route to the United States. As of November 2019, 13,089 – comprising 44% of individuals who applied for a humanitarian visa in 2018 – were still waiting. The United States has since closed its borders and enforced mass deportations in reaction to the pandemic.

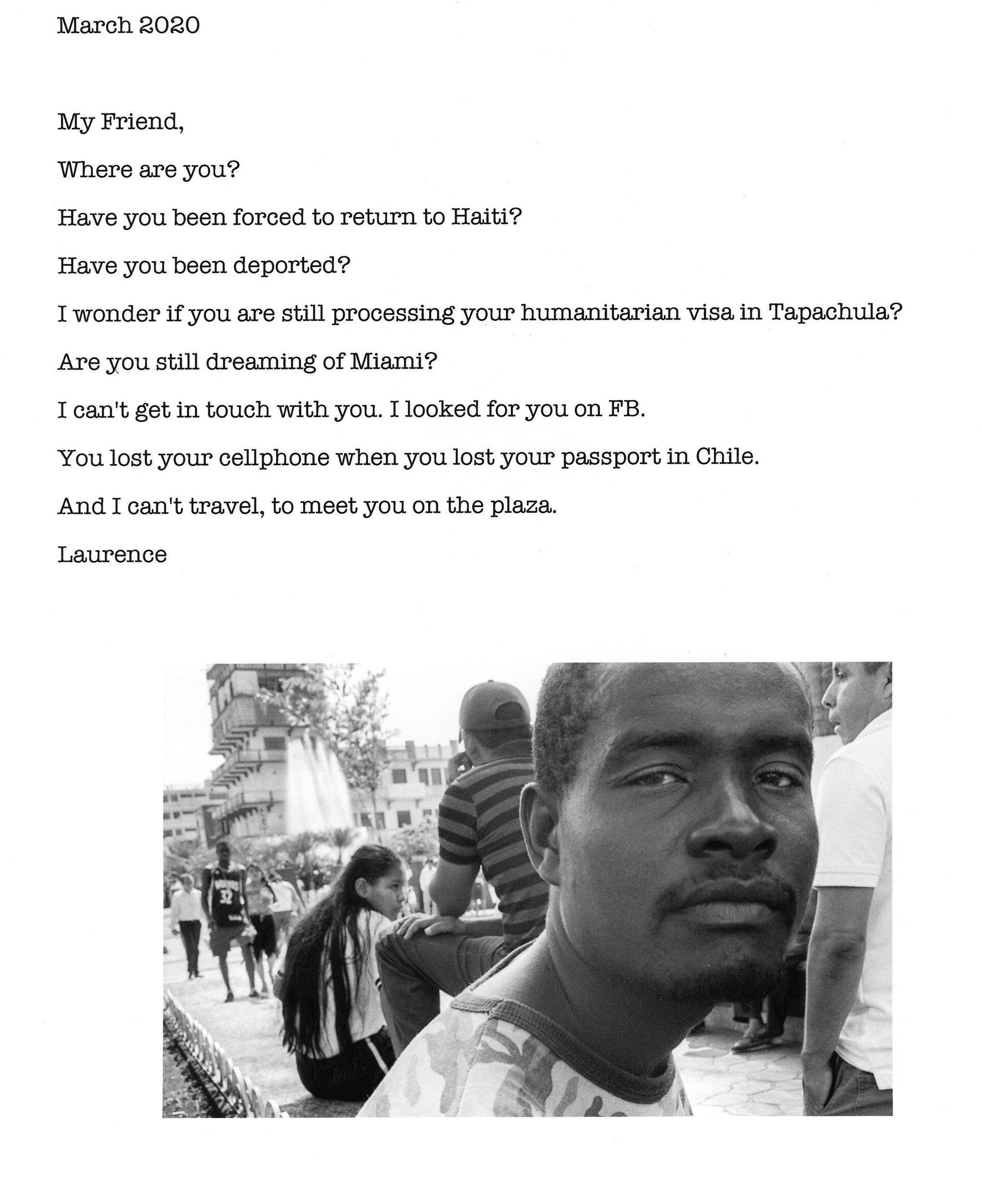

My Friend on the Plaza, Tapachula.

Barred from returning to Tapachula, I have no knowledge of the present circumstances of the people in my photographs. My letter to my Haitian friend, for instance, instantiates recollections of the diverse migrants I conversed with in the plazas and streets and whom I photographed while restraining myself from imagining their futures. At the time, I anticipated broken dreams in their attempts to reach the northern border, but I couldn’t have intuited the pandemic that was about to interrupt their plans, forcing them to go into hiding (if one can conceal being Black in Mexico, let alone one’s accent) or now deported to their countries of origin. But returning to West Africa, or even Haiti, is no simple endeavour. There is no possible narrative to make sense of their wounded and complex lives. In my conception of photography, the objective is to interrupt the troubled stories one may be tempted to thread together. Photographs constitute figures, not representations in the strict sense of the word. I accentuate their figurality by means of stitches, veils and paint to lead observers to question their representational nature.

***

Border Crossing between Mexico/Guatemala, Suchiate River.

Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, #1, Tapachula.

The region around Tapachula, also known as the Soconusco, is a major producer of coffee, cacao and fruit, among which bananas figure prominently as exports to the United States. The migrant route that I photographed back in November and December 2019 overlapped with two centuries-old corridors used by farm workers: the coffee and the cacao routes. These interlocking geographies, as if woven together, become a common ground for social structures, class, racism and other attempts to order the materiality of the world. If they’re lucky, migrants waiting for their visas can work in coffee plantations or cacao processing plants for pay that locals consider unacceptable. At the end of the nineteenth century, many Germans moved to Soconusco and bought land for plantations, and they were followed by fascists after World War II. Back then, they employed migrants from Guatemala.

***

In Chiapas alone, there were a total of sixteen migration and refugee detention facilities, all over capacity and with deplorable hygienic conditions. Yet, in comparison to northern border cities, like Matamoros, Tamaulipas, which borders Brownsville, Texas, Tapachula felt like a quiet provincial town. It wasn’t plagued by kidnappers and femicides like its northern counterparts, where life was and continues to be extremely dangerous.

Currently, I am not aware of the location of asylum seekers. It’s my understanding that a few of them have been able to resettle elsewhere, notably in Palenque, Chiapas, a city about 600 miles from Tapachula. The Mexican government, acting under pressure from the Trump administration, has not demonstrated respect for international law or human rights, though that hasn’t kept officials from trumpeting their record of solidarity with such tenets. An article in the Mexican newspaper La Jornada stated that, as a result of the pandemic, more than 20,000 asylum seekers remain in Mexico; though sympathetic towards asylum seekers (in order to provide the propagandistic spin that Mexico welcomes refugees fleeing political oppression), the article provided no information on where they’ve settled.Fabiola Martínez, ‘México, octavo lugar mundial en peticiones de refugio: Comar [Mexico Holds World Eighth Place in Requests of Shelter: Comar]’, La Jornada (Mexico), 21 June 2020.

The belief that the United States is a land of opportunity and wealth without discrimination and racism brightened migrants’ expectations. Hope of a better life kept people moving. Yet, with sadness, I anticipated that, even when they reached their destination on the northern border, they’d still face an uncertain reception and precarious future. In White America, Black and Brown bodies are systematically targeted while walking the street, driving a car, jogging, waiting for the bus – you name it. And even if I had told my interlocutors about the harsh conditions they’d face trying to cross the border, because they were trapped anywhere from Tijuana to Matamoros – the opposite ends of the 3,145-kilometre journey across Mexico – it wouldn’t have made a difference; at that point, returning home wasn’t an option.

***

In Prison City, processing papers with Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR) typically takes six to seven months. This time-consuming period involved interviews with and signatures from migration officers. It was a demeaning and, at times, life-threatening process. On the morning of 24 November 2019, I witnessed the killing of an African man standing in line in front of COMAR and the subsequent arrest of two men from the Central American gang Mara Salvatrucha, commonly known as MS-13. According to rumour, he was killed because he was supposedly cutting in the queue. I shudder when I think of the horrid violence migrants must have encountered after being expelled from Mexico in the aftermath of Covid-19.

***

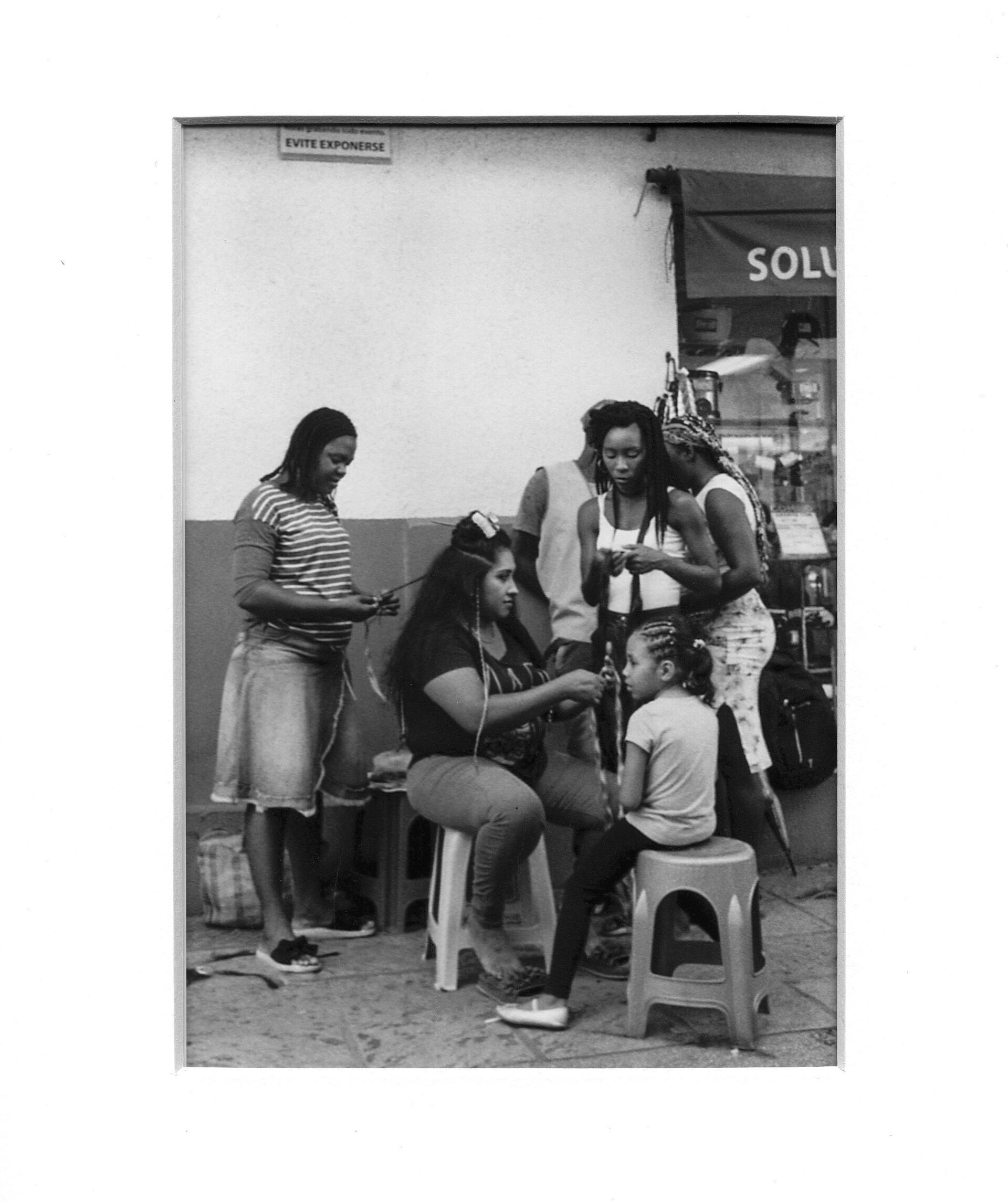

African women Braiding, Tapachula.

Singing 'Si te Vas', 'Paso Limon', Informal Entry Port between Mexico/Guatemala.

Migrant photography can offer powerful fictions about Western intellectual hegemony; it can claim to denounce migration policies, while, in fact, it may be contributing to their conservation and to what Ariella Azoulay called ‘regime-made disaster’.Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A political Ontology of Photography. (London and New York: Verso, 2015), 243. Neo-liberal and extremist policies coexist with a growing emphasis on the proliferation of visual scams in digital media. Garry Winogrand once famously stated that there’s no narrative in photographs. We can piece them together to tell a story, but they themselves lack a narrative: ‘They are mute. They don’t have any narrative ability. . . They do not tell stories. They show you what something looks like to the camera.’Garry Winogrand. ‘Garry Winogrand’ da Beat, video, 12:09, https://www.youtube.com/watchtime_continue=131&v=YQhZcKzbM9s&feature=emb_title One can assume the role of narrative interpreter to lend photographs meaning, if meaning and narration is what one desires. Personally, I see my photographs with zero narrativity. I strongly believe the anticipated futures of asylum seekers shouldn’t be subjected to an explanation or to stories that normalise and trivialise the events of their lives.

***

What sort of silence do mute images refer to in a world filled with voices and noises, a world in which one is expected to give a voice to the ‘voiceless’? Philosophers and social scientists have corrected the presumed absence of subaltern voices by developing ontologies, philosophies and juridical systems in need of recognition. These forms of knowledge are intended to replace individual and collective stories told from an unscientific point of view. In calling forth and constituting their voices, people assume an authority, a story that is supposed to explain their lives and one that they’re expected to take as truth. In doing so, we’re asking them to replace the story they’ve always told about themselves with authoritative (scientific) claims about the meaning of their lives. This leads to ethnosuicide.Laurence Cuelenaere and José Rabasa, ‘Ethnocide, Science, Ethnosuicide, and the History of the Vanishing: The Extirpation of Idolatries in the Colonial Andes and a (Few) Contemporary Variants’, Critique of Anthropology (2018): 53–74; Laurence Cuelenaere and José Rabasa, ‘Pachamamismo: O las Ficciones de (la Ausencia de) Voz’, Cuadernos de Literatura, no. 32 (2012): 184-205.

***

To the extent that photographs themselves recompose the relations between things, a new irreducibility of form eludes us. Perhaps it’s a question of seeing and abstaining from making sense of what we see in order to escape temporal determination? Whereas melancholia calls for a narrative with the purpose of comforting us, the manic takes flight from meaning-producing practices. This is the paradox of documentary and ethnographic photography.

All images © Laurence Cuelenaere.