Upon the announcement that the White finalists of the 2018 Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize had all produced portraits of Black sitters, the historian John Edwin Mason wrote on Twitter that the portraits, ‘like all of western visual culture, swim in a sea of white supremacist cultural flows ... like most creators & producers of western visual culture, [they] have not challenged those flows, those ways of seeing.’Mason, John Edwin. Twitter post. 18 October 2018, 8:45 a.m. https://twitter.com/johnedwinmason/status/1052948844504322048?lang=en

In a previous article, we asked why images produced predominantly by White, cisgendered men are chosen over images produced by historically marginalised photographers. Here, we want to explore the consequences of the continued prioritisation of the White, male gaze and the repetition of its visual tropes, both for photojournalism and broader society.

Colonial lenses

The origins of photography coincide with two important moments in history: positivism and colonialism. The core tenant of photojournalism, that photographs must represent the truth, comes as a hangover from the era of positivism into which the camera was born. In the nineteenth century, seeing really was believing, and scientific knowledge was restricted to that which was observable and reproducible. The camera was therefore used as a scientific instrument tasked with capturing an accurate, objective and truthful representation of the world.

The history of the camera is also inextricably linked to the colonial project. Photography has acted as an instrument of colonialism since its inception, beginning with the photographic application to anthropometrySpencer, Frank. 1992. ‘Some Notes on the Attempt to Apply Photography to Anthropometry during the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century’. In Anthropology and Photography: 1860-1920, edited by Elizabet Edwards. London: The Royal Anthropological Institute. and intimately connected to acts of appropriationSontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. London: Penguin Books. and objectification.Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang. These uses of photography, combined with the belief in photographs as true and objective representations of reality, underpinned and validated the colonial project in a way that other artforms, like painting or drawing, could not. Hannah Mabry explained:

That most if not all people believe each photograph appearing before them to be a truthful representation of its subject causes serious social issues. Photography, like any form of representation, was and is a social practice whose connotations were organized through cultural ideas and contracts … During colonialism photographs portrayed explicit cultural ideas, justified colonization, advertised empire, and represented different peoples and cultures, and fed into a racial discourse of European superiority.

Within any historical overview of photojournalism, it’s clear that colonial legacy has continued to dictate how the world is represented. Even the way that Africa is described today by industry professionals reveals how imbedded colonialism is in the institutions that govern our media. In a now infamous job advert for Nairobi Bureau Chief Michael Slackman, the International Editor for the New York Times, conjured up a fetishised image of Africa:

It is an enormous patch of vibrant, intense and strategically important territory with many vital storylines, including terrorism, the scramble for resources, the global contest with China and the constant push-and-pull of democracy versus authoritarianism.

Slackman’s words stem from a dominant ideology that continues to cast Africa, and notions of Blackness in the diaspora, through a colonial prism. The impact of this is clear; the advert seeks to employ a journalist able to continue its master narrative about Africa. Slackman’s ideal candidate must show ‘a commitment to understanding the needs and behaviours of our audience’, so no matter how contrite Slackman’s mea culpa, the advert is a clear signposting of the type of content the Times desires from its suppliers. There is no question that photojournalists who are unable or unwilling to produce imagery that conforms to Slackman’s desired narratives will not be reporting on Africa for the New York Times.

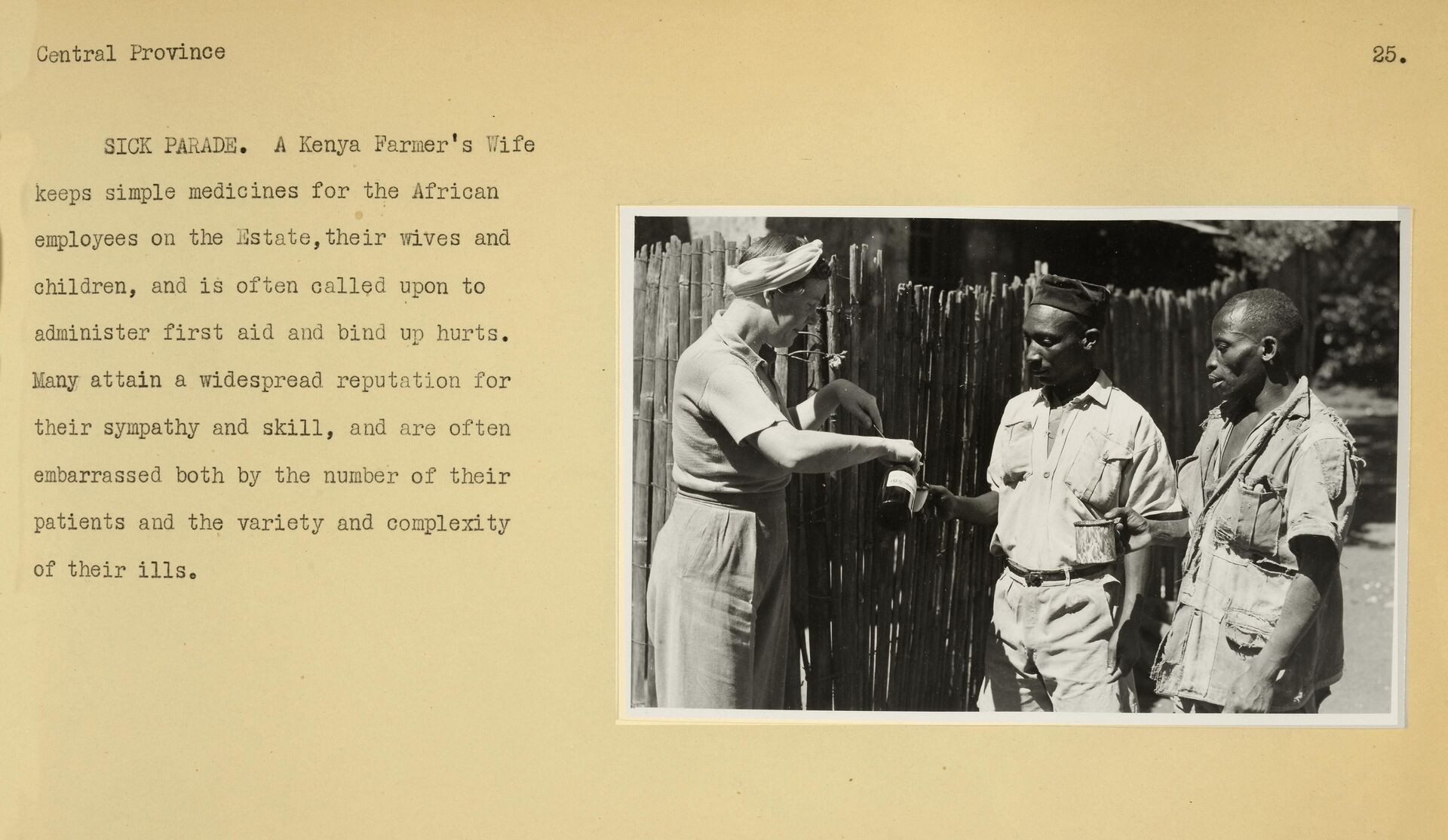

Medicine for sick farm employees, Central Province Kenya © The National Archives (UK), CO 1069 137 25, 1945

Perpetuation of the White, male gaze

If representations are to be seen as reliable and truthful, they have to be presented to us in ways which we already presume they exist, or in ways we’ve been told they exist, within the dominant ideology. Slackman’s advert, then, isn’t really just that of a Nairobi bureau chief; it’s an advert for the institutionalised perpetuation of a colonialist narrative. This is how stereotypes are constructed, maintained and continued.

But if editors are upholding the framework of the colonialist narrative, it is predominantly White, male photographers—and indeed some conditioned marginalised photographers—who are complicit in providing content that conforms to these tropes and stereotyped representations. Although we recognise that people will do what is necessary to find work in a competitive environment like photojournalism, there is, nonetheless, a lack of criticality. Max Pinckers writes about the repetition of tropes in photojournalism:

I don’t think photographers that produce such images are doing it on purpose ... I think it’s something that’s deeply ingrained into the subconscious. If a template-like image wins the World Press Photo award, it’s going to influence the next photographer going out into the field wanting to win the next World Press Photo award.

While job-seeking and trophy-hunting are key causes for the repetition of these photojournalistic tropes, we must nonetheless return to the gatekeepers responsible for prioritising the White, male gaze—and by extension, White male photographers.

World Press Photo reports that of 5,202 professional photographers from more than 100 countries over a four-year period, over 80% are male: ‘more than one half participating photographers are Caucasian/White’ and ‘only 1% of participating photographers classify themselves as Black.’ That’s means only 52 Black photographers participated in World Press Photo between 2015 and 2018. If the percentage of female participation holds true across racial lines, which is unlikely due to the double marginalisation of women of colour, then that means that no more than 10 Black women participated over a four-year period.

Let us be clear: this does not mean that there are only a few Black or female photographers. Instead, this makes it clear that Black, female and other marginalised photographers haven’t been supported, encouraged or otherwise enabled to produce photographs in the same way that White men have. This becomes evident when we look at the discrepancy in the representation of women in the industry at different stages in their career. Amanda Mustard states succinctly: ‘Female photojournalists go from a majority in university to the minority in the industry.’

This matters because we all bring our own life experiences to the table when we photograph a subject. Tara Pixley explained it best:

We shape the world in our own image: our individual understandings of truth and reality, our personal experiences and backgrounds do play into the scenes we choose to capture, how we frame them and whether we find them deserving of public dissemination. There is so much more to the photographs we take, select, and publish than aesthetics and the reality of any individual moment. Rather, each frame captured is a single millisecond in a sociocultural, historical reality that predates subject, photographer, and viewer.

When photographs reflecting a White, male gaze are invariably chosen above photographs presenting alternative perspectives, a trickle-down effect manifests as pressure on all photographers, regardless of their marginalisation, to conform to the accepted canons. As Lagos Photo Festival Director Azu Nwagbogu explained:

African photographers also tell these [White] stories because they think it’s what the West wants to see … They instinctively begin to follow these canons because they think this is what will get published.

African photographers and, to extrapolate further, photographers of colour in general, via their adherence to these canons, exhibit and replicate the very same form of Orientalism within their photographs, creating images which objectify and victimise—just like their White counterparts. Similarly, women photographers are forced to replicate the male ways of seeing and being in the world that have come to constitute ‘good’ photography.

Outside the house where Amy lived, Kingston, Jamaica © Andrew Jackson

Amy sleeping, Dudley, England © Andrew Jackson

Impacts of a dominant gaze

We’ve explained in this article that photojournalism has carried into the present two critical characteristics from its birth in the nineteenth century: our collective trust in its objectivity and a colonial lens that upholds certain representations of the world and silences others. By placing a higher value on representations that reinforce a colonialist and patriarchal view of the world, and by imbuing these images with the truthfulness commonly attributed to the photographic image, we’ve further inherited a limitation on the range of ‘truths’ that are represented in photographs. The danger herein cannot be overstated.

Photographs shape how we understand the world. They can confirm our prejudices or break them down. When the images we consume replicate patriarchal or colonialist tropes, these tropes become further embedded in our collective conscience.

Under the White, male gaze, women are fetishised:

The determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.Mulvey, Laura. 1999. ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. 837. New York: Oxford UP.

Hand nr. 1, Kingston, Jamaica © Andrew Jackson

Representations of Blackness and people of colour take on a problematic, crisis-driven aesthetic, by showing people as always violent, bestial, broken, inferior or dead, as Sarah Sentilles aptly points out:

Publishing some images while suppressing others sends the message that the visible bodies are somehow less consequential than the bodies granted the privilege of privacy … ‘The more remote or exotic the place, the more likely we are to have full frontal views of the dead and the dying,’ Sontag wrote. But 15 years later, her words are not quite true. Sontag’s sentence could be rewritten: The darker the skin, the more likely we are to have full-frontal views of the dead and the dying, even when those suffering bodies are just across town, down the street, right next door.

These representations effectively serve to reify sexism and racism. They do not create empathy with the viewer; they subjugate women and place Black bodies away from any notion of the perceived normality reserved for Whiteness in our visual landscape.

On the other hand, Tara Pixley points out that it’s the humanised images—images like ‘peaceful protesting en masse and black communities working harmoniously’—that ‘evinc[e] empathy rather than a paternalistic sympathy.’ When there’s a dearth of these kinds of images, we’re left with an empathy gap, or an inability to relate to or understand individuals with different lived experiences.

Photographic representations do not only shape how we understand others, they also shape how we understand ourselves. Daniella Zalcman wrote that ‘The way others see us, and the way we see ourselves, are not always aligned.’ Therefore, there are consequences when others are responsible for constructing our image in the media:

Photographs don’t just tell us stories, they tell us how to see. So when representations of womanhood, the female body or femininity are largely constructed by men, it’s not just that they define us, they teach us how to see ourselves.

Photojournalistic tropes can even shape the trajectory of our lives. Leigh Donaldson wrote the following about a 2011 study, Media Representations & Impact on the Lives of Black Men and Boys:

…negative mass media portrayals were strongly linked with lower life expectations among Black men. These portrayals, constantly reinforced in print media, on television, the internet, fiction shows, print advertising and video games, shape public views of and attitudes toward men of colour. They not only help create barriers to advancement within our society, but also ‘make these positions seem natural and inevitable’.

Just as important as the impact of how subjects are represented is the impact of when subjects are not represented at all. What are the consequences of not seeing yourself represented? How does this affect someone’s sense of belonging, their ability to express themselves to other members of their society and their own self-image? Robin R. Means Coleman explains that these omissions are not a kind of stereotype, as stereotypes ‘actively signify that which is a present and identifiable, constructed image.’ Instead, these omissions are a kind of ‘systematic annihilation’ of marginalised groups.

Sea nr. 1, Montego Bay, Jamaica © Andrew Jackson

Challenging photojournalism

Within his role as a World Press Photo judge in 2009, Stephen Mayes asked the question: ‘What is journalism if it doesn’t inform but merely repeats and affirms?’ However, a lot has changed in ten years. The immediacy of social media and the accessibility of the camera has meant that photojournalism is no longer the domain of an elite few. As Margaret Simons explains: ‘Today, just about anyone with an internet connection and a social media account has the capacity to publish news and views to the world. This is new in human history.’

This democratisation is a critical step towards a photojournalism that reflects the diverse range of narratives that exist in the world. This comes with a responsibility for photographers to recognise that not every story is theirs to tell and to reflect on the question: am I the best-placed person to tell this story? If the answer is ‘no’, then perhaps there are other ways of enabling those who are best placed, for example by seeking out photographers from the community in question or by facilitating participatory photography practices.

But diversity in storytelling is not enough. As we have explained, even some marginalised photographers have internalised and reproduced the same perspectives and stories. Therefore, we need to actively interrogate the messages our photographs are sending, what tropes they invoke, the harm they do and what stereotypes they rely on. We do this by heightening our sensitivity to the visual language we employ, recognising that aesthetic choices are not benign. These choices carry with them their own coded messages that have the power to either reproduce or subvert stereotypes. Going back to the words of John Edwin Mason, we need to challenge cultural flows. We need to redefine the visual language of photojournalism if we are to subvert the White, male gaze and its ways of seeing in the world.