Exhibitions are, by nature, ephemeral events. What remains after the show is over? They do leave a residue, and it’s important we get an idea of just what that is.

Photography is, for instance, a privileged tool for capturing the ephemeral. The immortality of the pose melts into the camera lens, determining the photographer’s aesthetic and formal intentions; but at the same time, in a situation as peculiar as that of a World’s fair, the permanence of the photographic shot inevitably clashes with the ephemerality of the event.

Historical debate considered photography, especially when interwar international exhibitions as venues are discussed, as a medium between art and the technical and political products of commerce and industry. Even today, this duality makes photography a useful means of serving commercial purposes and conditioning masses via advertising and documentation. The message conveyed through the medium of photography has hence fostered a closer rapprochement between the general public and the political establishment. In 1935, when these dynamics were first beginning to manifest, photography invited the public to a collective, unintentional participation, allowing a broad, coherent view of ease and modernism in which architectural structures were rendered visible in the manner of a spectacle. As a metaphorical expression of universal character, photography through World’s fairs became the concretisation of cultural and technical liberties.

The Belgian photographer Willy Kessels (1898–1974) perfectly embodied this complex and dual nature in World’s fairs photography: on the one hand, he had the awareness of having to respond to clients’ requirements, and on the other, he enjoyed the aesthetic and artistic autonomy of a photographer who didn’t renounce his clear and authentic vision of the world. Apart from working on commission for advertising and other purposes, Kessels had a clear artistic and autonomous vision. In photo history, he’s also seen as one of the most important representatives of a modernist new photography style in Belgium that broke with the rigidity of post-pictorialism and traditional studio photography.

The discovery of Willy Kessels’s photographic Belgian store (primarily in the archives of the FOMU in Antwerp, the CIVA – Centre International pour la Ville et l’Architecture– in Brussels, and the Museum of Photography in CharleroiTo learn about the inorganic condition of Kessels’s archives and for a comprehensive study of his work, see Laure Nicod, ‘Willy Kessels. Photographie d’architecture’, (master thesis, Faculty of Architecture La Cambre, ULB, 2014-2015), director Irène Lund, p. 10 and 225-229. Thanks to Irène Lund for the communication.) was absolutely crucial to the exhaustive comprehension of the Italian section at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1935.The lack of iconographic information on the Italian section in Brussels was particularly downhearted: many documents and publications but little photographic evidence. Always the same persistent postcard clichés, pictures scrolling seamlessly from one book to another. Kessels’s photographic documentation was crucial for the completion of my doctoral thesis, defended in 2019, on the framework of the international agreements between the University of Florence and L’Université Libre de Bruxelles (promoters Prof. Luca Quattrocchi and Rika Devos): ‘The Italian Section at the 1935 Brussels Universal and International Exhibition: Reconstruction of a multiform identity among art, architecture and propaganda’. Further, it constitutes an unprecedented and precious reserve for the overall understanding of the photographer’s aesthetic power and methodological practice in capturing ephemeral events: from the technical devices used to shoot buildings and photography’s design process in the mounting of a constructivist style to the importance of luminous contrast and from the interest in artificial light to the development of a real poetic landscape that would become a strong point in his photographic campaign for the Brussels Exhibition of 1935 (and again in 1958).

Building Architecture for Photography

For Belgium, 1935 represented the year of the Universal Fair: In 1935, Belgium hosted the World’s fair, a stimulus to the fervent imaginations of not only visitors but, above all, photographers, both professional and amateur.

The particular shape of the exhibition site as well as the proliferation and architectural significance of the buildings and the development of green spaces and gardens would have huge impacts on the evolution of photographic practice. Over all, the introduction of artificial night lighting was remarkably crucial. As Ruth Hommelen pointed out, ‘[it] was not the creative power of the architect which has provoked this incredible metamorphosis of the night. Those responsible for these new nocturnal cityscapes were the advocates of the advertising industry, which had long understood the drawing power of artificial light and illuminated signs.’See Ruth Hommelen, ‘Building with artificial light: architectural night photography in the interwar period’, The Journal of Architecture, no. 21 (2016): 1063.

The photographic reportage for the Brussels World’s fair was primarily demanded by the organizational fair Committee to the company L’Epi-Demolder and to Emile Sergysels, another expert in architectural photography, in addition to a very long list of professionals. Photographers were invited to participate in a sort of collective campaign that converged into an extensive and diverse range of products for advertising and merchandising purposes, with a strong dissemination of photographic images. Beyond the important political implications that marked his private life and artistic career, Kessels would become engaged in exhibitions and World’s fairs on many fronts: as a curator, jury member, and, invariably, one of the most appreciated official photographers.

An Artist and Photographer Focused on Architecture

Trained as an architect and artist in Ghent (first with an interrupted study period at Sint-Lucas, then at the Academy of Artswith a specialization in sculpture) Kessels’s hybrid education was essential to his developing his multiple talents, his later aesthetic path, and his position as a close partner to architects.

His wood and metal models, halfway between cubist handcraft sculptures and new modern-style furniture, are immortalized in his photographs from the mid-1920s with surgical precision and a striking chromatic contrast. They were already symptomatic of his innate sense of space, of the depth of his subjects’ choices, and of his penchant for dramatic directional lighting, all in a renewed vision of the ‘psychology of architecture’.According to Heinrich Wölfflin’s 1886 definition.

Like most of his peers,Just consider László Moholy-Nagy or Alexander Rodčhenko. no other medium but photography would work for him and define his entire philosophy. Then, there was his post-production work with superimpositions and photomontages, of which he was certainly no pioneer but on which he imposed a new and recognizable trademark. In his evolution, he came close to the constructivist positions and perspectives embraced by the Czech Karel Teige: ‘In its current forms, photomontage is on the one hand the result of the analytical period in painting and on the other the result of modern advertising and political propaganda, which has found a very expressive and effective means of combining verbal and figurative communication, text and photography’.Teige. Arte e ideologia 1922-1933, curated by Sergio Corduas (Torino: Einaudi, 1982), 189-202. Translation from Italian by the author.

From being a participant in the Paris International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative Arts in 1925,He was called to hold the architecture stand Het Binnenhuis. he found himself in the role of photographer capturing the Brussels’s World’s fair ten years later, accumulating in the interim a series of marking experiences. For Kessels, the 1930s coincided with a revelatory juncture: the decision to devote himself entirely to photography with a greater and more refined sensitivity, the rediscovery of Brussels, and fascination in architectural modernism. The five years leading up to his participation in the Universal Exhibition were full of commitments that would inevitably mark his prolific activity, starting from the highly original photographic apparatus for the editions Découverte de Bruxelles and Bruxelles atmosphère 10-32 (by Albert Guislain, respectively 1930 and 1932) and Synthèse d’Anvers and Ons Antwerpen (respectively by Roger Avermaete and Eugeen De Ridder, 1932) in which Kessels captured the signs of transforming cities, finding in photomontage and night light a privileged means of expression, as Georges Champroux and Brassaï did at the same time. He succeeded in making cities almost unrecognizable, even to the most expert eye; in his work, the best-known architecture seems to fade away and lose its specificity, adapting to a subjective, purely plastic interpretation in which light sources seem to emanate directly from subjects.

In the years that followed, he was engaged as director of photography for the socially engaged film Misère au Borinage (1933, republished as a photographic reportage in the illustrated Belgian magazine A-Z) and a significant participation in the Brussels International Exhibition of Photography and Cinematography at the Palais des Beaux-Arts (1933).

His close proximity to the Belgian modernist architectural milieu, in the apogee of modernist architecture, enabled him to establish close links with the most influential designers of the time and of all different provenance (first and foremost the very modernists Henry Van de Velde, Victor Bourgeois, Joseph Diongre, and Maxime and Fernand Brunfaut; and the most traditionalists and eclectics Michel Polak, Paul Bonduelle, and Adrien Blomme) who would involve him in the photographic cataloguing of their productions and their publication in specialist magazines (as L’Emulation, the official review of the SCAB – Société Centrale d’Architcture de Belgique –, the architects’ representative body; La Cité; BATIR; Revue documentaire, for which he became resident photographer, as well as the aforementioned A-Z).

Willy Kessels and Giulio Parisio: What Photography for Whom?

As the main promotor of modernist architectural photography, Kessels intrinsically dealt with construction companies, through which, with plausible certitude, he was able to obtain an important role in Brussels’s 1935 fair. Especially noteworthy is his long collaboration with the Belgian company Entreprises Générales et Matériaux (ENGEMA), responsible for many of the constructions on the exposition site, including the central Heysel Palace V and some of the Italian pavilions, like the Littorio building , the Rome pavilion (named Ville de Rome), and Tourism and Textiles pavilions. For ENGEMA, Kessels was directly entrusted with numerous brochures, leaflets, and photographic documentations that bear witness to the history of the construction company and, at the same time, to Belgium’s urban, architectural, and electrical transformation.See Nicod, ‘Photographie’, 151. Particularly noteworthy are the works commissioned from Kessels by ENGEMA for a retrospective album of Brussels 1922–1932 and another album on the construction of the site and pavilions of the 1935 World Fair. The publication would turn into an article published in La Cité, no. 5 (1935), 13. Even more importantly, the fair’s organizing Committee was planning to have Kessels place large photomontages on the facades of one of the pavilions under construction. But that all ended in an unfortunate stalemate: when Kessels was already engaged in the project and requested compensation, the Committee claimed that it had only asked for an estimate.See letter in General Archives of the Kingdom, Brussels, Folder 59, particular correspondence from the General Secretariat, Willy Kessels quarrel, 31 July 1936: ‘[Kessels] had been called upon…to submit to us projects for the extension of industrial views to decorate one of the façades of the Textile Pavilion’. Translation from French by the author.

In this regard, Kessels’s work for the Italian section of the 1935 Brussels’ Fair is as tangential as his Italian counterpart Giulio Parisio (Naples, 1891–1967). Their professional lives, as we shall see, intertwined on the immense photographic set of the Brussels World’s Fair.

With due distinction, Giulio Parisio shares with Kessels remarkable similarities. Like Kessels, Parisio received an artistic education before being a photographer and grew up under the influence of the southern Futurist movement. Like Kessels, he had his own gallery that attracted many Italian and international artists and intellectuals of the time. Also like Kessels, Parisio’s style focused on photomontage and on innovative backlit panels, very effective for so-called advertising photography. By opting for optical distortion effects, the creative use of shadows, and the superimposition of images, Parisio diversified his artistic productions, combining the needs of public and private clients with his own aesthetic inclinations.

From the 1925 Paris International to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair and 1935 Brussels one, not to mention on countless occasions in his homeland, Parisio linked his profession as a photographer to official commissions, conveying a seemingly recognizable, modern, and distinct Italian image in mass events that were supposed to break away from interior propaganda. With the consolidation of the fascist regime in the 1930s, Parisio multiplied his photographic experiences at exhibitions and World’s fairs in which he played an important role. His participation in Brussels was, for instance, closely connected to his previous engagement as an advertiser for the Italian semi-public Tyrrhenian shipping company, a post he’d held since 1933. The photographic glorification of the Navigation national pavilion throughout photomontages apparently steered him away from his advocacy for interior nationalism.

The same paradoxical antithesis between the curiosity of the photographer and the rigidity of the right wing movements can also be noticed in Kessels’s known proximity to Joris van Severen and the Verdinaso movement.The Flemish Verdinaso, founded in 1931, was an authoritarian, fascist-inspired movement steeped in ideas related to corporativism. However, there seems to be no causality between their political affinities and their professional positions as photographers. These modernist photographers identified with right wing political ideals, and that undermines the common association between modernism and socialism.

Willy Kessels and the Brussels World's Fair

A global architectural eclecticism was invested in the panorama of the exhibition site, from hybrid monumentalism to vernacular traditionalism, from fanciful Indigenous exoticism to captivating rationalism. In the ample space granted by Belgian promoters, among gardens, fountains, light games, and varied places of attraction, Italy displayed a fragmented architectural scenario of fifteen composite structures. A few flashes of modernism didn’t escape Kessels’s attentive eye, as the photographic examples examined in this segment will demonstrate.

In a rugged, flourishing landscape, the Italian section in Brussels didn’t leave fairgoers and experts indifferent: in an attempt, not always successful, to blend modern architecture and technology with a classicist, vernacular language, the fascist message, through manipulations and explicit architectural references, wanted to prove itself renewed and revolutionary, finally detached from the pompous and monumental language of its Italian homeland. In his extensive reportage dedicated to the Italian section, the commission of which may’ve derived from his involvement with ENGEMA, Kessels focused his vision on some of the most significantly avant-garde pavilions, confirming his indisputable style and the specificity of his entire optical and photographic process, from the choice of the architectural subject to the pose.

Brussels, World Fair of 1935, the Italian Pavilion. Willy Kessels © 2021, SOFAM

Littorio pavilion © Archivio Fotografico Parisio

AAM-WK-459-03, CIVA Archives. Willy Kessels © 2021, SOFAM

In several photographs dedicated to the Littorio pavilion, built by ENGEMA from a project by architects Adalberto Libera and Mario De Renzi,FoMu Archives, Antwerp, P_1992_0033. There’s a similar version in CIVA’s archives (WK-171A- 509). In the latter, the pose is more oblique and the shot is taken from the right side of the building. Kessels opted for a dramatic, almost theatrical vision, through a foreshortening cut-out and a typical oblique, inclined pose. The exploitation of the full potential offered by the architectural structure and the way the building has been captured could influence, if not determine, its overall perception: the highlighting of its bright transparency, of its impressive shape, of its dynamism and its technical and modern accomplishments. The dramatic light contrast came from the shadows created by the four enormous iron and glass lictor fasces (borrowed from ancient Rome) that covered the façade and the repetition of the quadrangular holes in the structure, which illuminated it at night and created a striking optical effect. The introduction of the human figure, whose black shadows are projected onto the white marble stairs that preceded the entrance to the pavilion, becomes a functional artistic device to the rendering of the building’s magniloquence.

Surprisingly, the same viewpoint can be found in Parisio’s repertoire: one of the photographs taken of the Littorio pavilion, collected in a splendid album for personal and professional use, shows an affinity with Kessels’s vision. Just look at the same foreshortening with the monumentalized perspective from below, the same 45-degree rotation, the same vegetal element and the staircase leaning against the side of the mammoth pavilion, reminders of the building’s inhuman proportions.

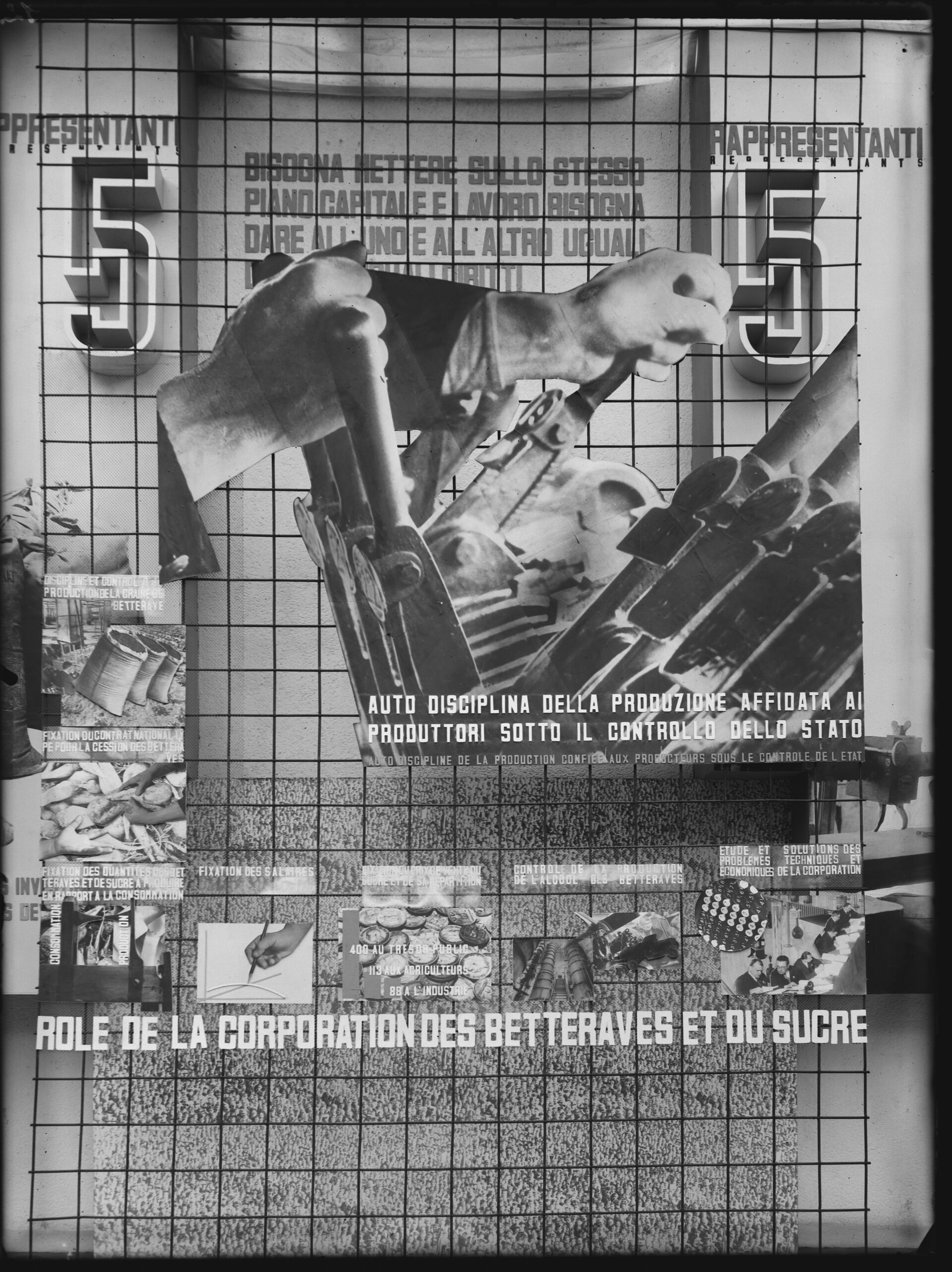

In his photographic reportage, Kessels’s interest on the Littorio pavilion was investigated via a new optical perspective offering a new sense of the subjectivation of space, of a meta-photographic inquiry. The pavilion was lavishly decorated with photographic elements, which was rarely the case for an Italian fascist building at such an important national event. But the particular circumstances of the Brussels site and the desire to convey the new fascist corporative message through modern language facilitated the extensive use of the photo mural in the Italian section. The main halls were literally invaded by photography in all its forms and expressions: from the blow-ups of Mussolini at the entrance to photo montages and collages with pictorial and typographical elements to huge enlargements suspended from the ceiling and towering over spectators. Kessels focused on a particular wall of photographic montages of clear constructivist inspiration. The photographic montageRealised by Erberto Carboni and Giaci(nto) Mondaini, two artists and graphic designers very well known in Italy in the 1930s for their intelligent, modern advertising campaigns. showed the positive effects of fascist corporatist politics through a simultaneous synthesizing of human and industrial landscape. The formal elements of repetition, also dear to Kessels, were applied to a large extent in magazine advertising compositions and were closely tied to the so-called revolutionary political and aesthetic messages. The visual impact of Kessels’s photography was based on close-up shooting and clever juxtapositions of light and shade effects (chiaroscuro); the photographer’s eye lingered on the detail of the disembodied hands operating the machine, emphasizing with clarity and intelligibility the outlined elements in the background.

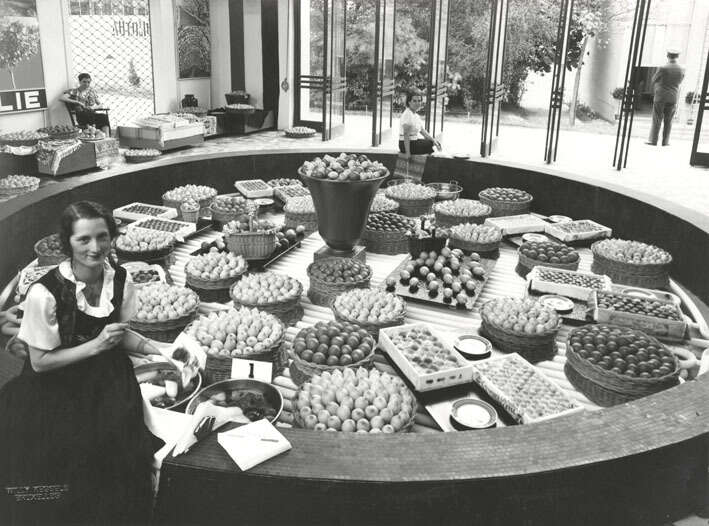

The Fruits and Vegetables Pavilion

Kessels showed a marked scenographic sensitivity in the Fruits and Vegetables pavilion, unanimously considered the truthful masterpiece of the exhibition’s Italian section and of Luciano Baldessari, its creator and architect. Although there are no direct links with the ENGEMA – Entreprise Générale et Matériaux – company (in this case the less-known CET, Construction, Entreprises, Travaux company was in charge of the construction), it’s highly probable that Kessels became interested in the pavilion because of its appealing design and at the behest of the exhibition’s General Committee. Conceived as a real Italian market, with indoor and outdoor areas connected by large mosaic spaces and a fountain as well as fresh food and wine, it was also inhabited by large photographic-pictorial panels. Some of Kessels's shots are held in the archives of Charleroi and Antwerp.

From the FOMU archive. Willy Kessels © 2021, SOFAM

From the Charleroi Photographic Museum Archives. Willy Kessels © 2021, SOFAM

In the following photograph, Kessels’s vision of the pavilion is totally renewed and peculiar in relation to canonical photographic reproductions of the building. Avoiding the cliché of the cubic façade in a frontal view, the photographer opted for a view of the interior, and in particular from the courtyard, which was the junction of the two architectural blocks. The customary oblique pose to which Kessels had accustomed his audience, aligned with the viewpoints of Moholy-Nagy and El Lissitzky, allowing him to record, in a single shot, all the decorative and architectural elements indicative of the pavilion’s style. Fascinated by the concrete, glass, and metal construction, Kessels opted for a towered, geometric juxtaposition of architectural elements at different heights and their confluence in a perfectly ordered environment. The chromatic effect that characterises the shot is of great impact, rendered by a delicate scale of whites and greys and with meticulous control of high-angle pose.

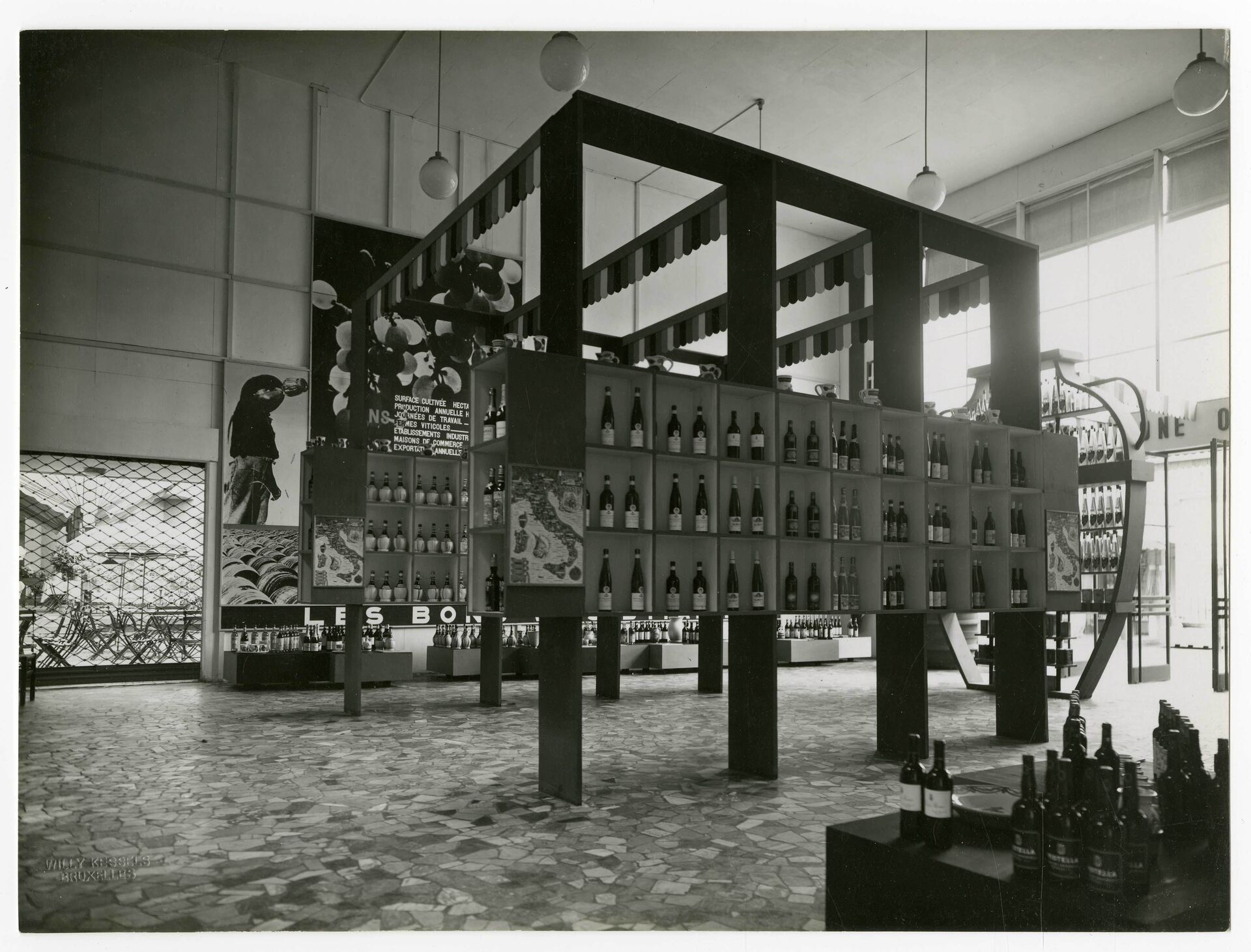

Another photograph introduces the viewer’s gaze – a strictly oblique gaze again – to the Oils and Wines room, the low angle suggesting the almost complete openness of the space. Kessels showed his skill in achieving certain technical heights. In a new metamorphic, almost metaphysical dimension, the photographer, led by the natural light flooding through the glass windows, participated in a dialogue between the indoor and outdoor spaces.

The exploitation of natural light design, with a pronounced chiaroscuro, nearly in black light, and a less vertiginous viewpoint, more frontal and from a greater distance, drops the pavilion in a blazing sun. From the back emerge, dazzlingly, the café, the large gazebo, and the wall dominated by an unfailing photographic enlargement of grapes, reminiscence of rounded chandeliers, and the chromatic contrast of the mosaic floor (which, moreover, doesn’t seem far removed from the compositions of the aforementioned Erberto Carboni).

The subtle but significant change of aesthetic and emotional impact can undoubtedly be detected in a photograph that concludes this short drive through the Italian section in Kessels’s work. In this shot, the photographic intention shifts from the architectural matter to, it seems, an even more personal approach. We’re still in Baldessari’s pavilion, but we’re in the entrance hall, not far from the other pavilions of the section; it’s broad daylight, and the sun penetrates the space with all its strength and chromatic warmth. Kessels captured a moment of rare attractiveness: in the large space inhabited by an enormous pool of luxuriant fruit and vegetables, the photographer called on the human figure. The purity and intensity of the gaze of the woman in the foreground, seated on the edge, the more mischievous expression of the other two in the background, in the total indifference of the caretaker from behind, suggest a moment of historical veracity, almost totally absent from the absolute purism of Kessels’s architectural photography. Even if Kessels’s research and practice were extended over a very large catalogue of photographic production, it’s also true that the public and exhibition photography of the 1930s seems to have been largely based on images deprived of human bodies.

As was the case with Giulio Parisio, whose photographic album on Brussels turned out to be a veritable kaleidoscope, Kessels didn’t renounce the themes that were dear to him – the original framing, the chromatic contrast, the plastic approach to the subjects – adding to the reportage a complementary folkloric element, emotionally and anthropologically essential and comprehensible in a World’s fair.

The Continuity of Gaze towards Expo 1958

Artistic reporter, photojournalist, and publicist, Kessels had a career that’s difficult to label or define, and so did Parisio. Kessels’s participation in Brussels’s World’s Fair can help us further understand his role as the main representative of modernist photography in the Belgian architectural scene. Indeed, he was directly involved in the process of disseminating the works of the modern movement through photographic reportages. At the same time, it also provides valuable general information on the evolution of the profession of photographer in the mid-1930s. Kessels made his living from photography, as was amply demonstrated by his numerous projects, which were the results of an established clientele commission. From collaborations in magazines promoting, enhancing, and disseminating architectural objects to the photo albums of construction companies such as ENGEMA, key players in the transformation and modernisation of Brussels, Kessels’s choices couldn’t have been random. Through his unmistakable and immediately recognisable style, the autonomy and distinctiveness of Kessels’s photography becomes an effective advertising business card for his clients.

In the difficult years between the exhibition until the end of the war, his official role and commissions seemed first to shrink and then to vanish. Disavowing recent fascist implications, his intimate seclusion that shaped his sophisticated work and photographic process was interrupted in late 1950s. His strong relationships with construction companies led him to another important commission, namely the photographic architectural campaign for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. Closely aligned with the vegetal design, he avoided the experimental technical process of new modern architecture, focusing on the poetics of gardens and fairgoers, which became phantasmal presences functional to the visual and emotional proportion of the natural elements and architectural construction. Embedded with the vibrant interwar exhibition culture, he kept as a legacy the plastic and lighting tension that pervaded the sense of space as well as the unmistakable oblique pose, which opened the gaze towards a new, wide, bird’s-eye perspective.

While continuing to contemplate photography as a pragmatic approach to the architectural conception and propagation of modernism, Kessels’s explicit intimate variation seems to have led towards a greater abstraction, echoing a different, self-conscious visual strategy.

In a much broader and more complex historiographical context that identifies the photographic reportage of exhibitions as a unique and autonomous genre, ‘what founds the nature of Photography is the pose....In Photography, the presence of the thing is never metaphoric....Photography, moreover, began, historically, as an art of the Person: of identity, of civil status, of what we might call, in all senses of the terms, the body’s formality’.Roland Barthes, ‘Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography’, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1979) trans. by Richard Howard, pp. 77-78.

This Roland Barthes quotation, an unfailing reference for each photography researcher, seems perfectly tailored to explain this insight into Kessels’s photographic practice and methodology in the context of the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair, involving the role and the perception of fairgoers in these extraordinary occasions. A binary correlation can therefore be established between the thing – that is, the ontological, the intangible body of architecture conceived for international exhibitions and therefore intrinsically ephemeral – and the body’s formality, which might be considered as the perceptive sensitivity of the photographer towards the photographic subject, its presence, and its all-embracing significance in a specific historical and political context.