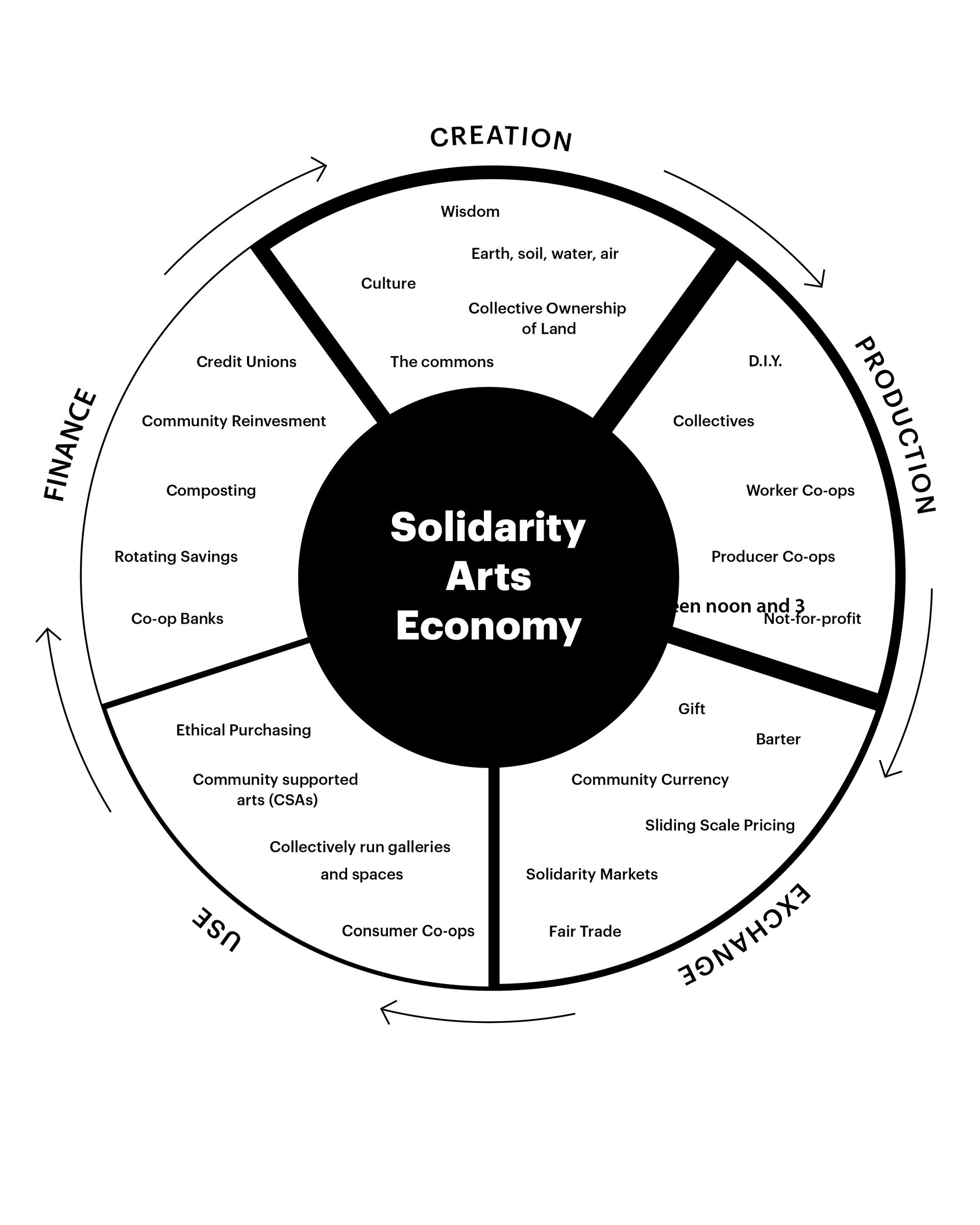

This Solidarity Economy diagram has been adapted from Ethan Miler’s diagram and was designed by Topos Graphics for the book Making and Being by Susan Jahoda and Caroline Woolard (Pioneer Works Press / DAP, 2019).

If ever there was a time to dream up art worlds that work for artists, this is it. What are the art worlds that you want? Who do you want to be in community with? Where do you want your artwork to go, after you make it?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more people agree that the dominant “art world”—a term that signifies all of the people and networks and organizations that enable the learning, discussion, making, presenting, and circulation of art—is not functioning as so many of us artists would like it to. As art critic Jerry Saltz wrote in April of 2020:

The mighty Met estimates it could lose $100 million and has announced widespread layoffs; the Hammer Museum laid off 150 part-time workers; L.A. MoCA laid off its entire part-time staff; S.F. MoMA expects to lay off 135 on-call staff members; Mass. MoCA is laying off 120 employees. Meanwhile, many maintain restoration labs, care for vast collections, pay insurance premiums, electric bills, and thousands of other unseen costs. Other than the Getty, Kimble, the Met, and MoMA, most museums don’t have vast endowments that can allow them to get through [a pandemic] like this.1 https://www.vulture.com/2020/04/how-the-coronavirus-will-transform-the-art-world.html

Beyond prioritizing insurance premiums over employees, the art world is too white, too colonial, too extractive, too hierarchical, too male, too straight, and too market-driven. And yet this realization—of the dominant art-world’s limitations—occurs during every capitalist crisis; every decade or so now, it seems. New art worlds were dreamt into existence by artists in 2007/2008 as well as in the long down-turn of the 1970s fiscal crisis.

New art worlds are dreamt into existence in every crisis. For example, as I write:

- the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives has just launched a national worker-owned freelancer cooperative;

- artists Vallejo Gantner, Alex Reeves, Erica Schnitzer, Chet Kerr, and James Dennin started the online marketplace hireartists.org to give work to “accomplished, dedicated practitioners from across the arts [who can] share their knowledge or to help with creative and everyday needs”;

- artist Linda Goode Bryant and cultural worker Sarah Workneh opened a free and expanded food pantry to “help supply and supplement the already at-risk communities of Brownsville and East New York”;

- and President Sanjit Sethi of Minneapolis College of Art and Design has announced that the school “will offer immediate, temporary space to be used by organizations and nonprofits that have been displaced.”2 Sarah Workneh, personal email, May 6, 2020, and MCAD newsletter June 2, 2020

And initiatives of mutual aid, solidarity, and cooperation need not be unique to a crisis. In fact, these art worlds are dreamt into existence every week by artists and people who survive the daily “crisis” of being told that we are not valuable, that we should not exist, that we need to continually justify our own existence.

Take a moment to sense the spaces, networks, and communities created by artists around you. Sense the art worlds led by Black, Indigenous, and Artists of Color, by disabled artists, by trans artists, by queer artists, by nonbinary artists, by neurodivergent artists, by undocumented artists, by immigrant artists, by poor artists, and by so many people who are not only surviving, but thriving, in art worlds of cooperation and mutual aid. Artist-centric networks, organizations, and initiatives—in short, solidarity art worlds—are not only possible, they already exist.

Allow yourself to sense the power of these art worlds around you, and allow yourself to dream into the art worlds that you want. Rather than waiting to “go back to normal,” to an art world and system of production and distribution that works for very few people, now is the time to dream.

Allow yourself to dream.

Allow yourself to dream with friends.

I am going to invite you to dream with me. In this dream, we are going to move into a body of calm, gentle, warm water. Sense this body of water. Take in the smells, tastes, and feelings around you. This is a dream about what the arts can do. You are in a body of water.

1. Sense the body of water. As a gentle wave laps against you, you remember a moment when you chose to be in the arts, or the arts chose you. Despite a dominant culture that values reading, writing, and speaking, you made a commitment to drawing, moving, or singing—to visual and embodied ways of knowing. You are told that you are stupid, passionate, stubborn, or crazy because you live in your imagination. This lack of respect for the arts continues to make you feel alone, but you have survived, and your persistence is part of your strength, your internal power that no one can take away from you. A gentle wave moves toward you. How do you feel?

2. A second wave laps against you. You are told that you will never get a job, that you will be a “starving artist” in the United States, and you understand this to mean that artists are not paid well, that the arts are not well funded in the United States. You want to be an artist anyway. You are told you are stupid, passionate, stubborn, or crazy. The impossibility of making a living in the arts makes you feel alone, but you survive, and your persistence becomes part of your strength, your internal power that no one can take away from you.

3. A third wave moves toward you. You come to realize that the arts are devalued like all work that sustains life, all work that allows people to rest, dream, and return to work the next day (what is called social reproduction). You come to understand that the arts are aligned with service work, domestic work, sex work, agricultural work, healing work, educational work, spiritual work, social work, and all racialized and gendered labor in the United States that is not compensated adequately. You realize that the people who do all of these kinds of labor have been told that they too, are stupid, passionate, stubborn, or crazy. You now know that you share this internal power, together.

4. A fourth wave moves toward you. You begin to wonder: If the artistic work required in order to collectively celebrate, to communicate without words, to draw, to dance, to sing, to build shared symbols and imagined futures, to raise children, to clean homes, to collect the garbage, to grow food, to heal, to learn, and to connect is not compensated or supported, how does it continue? How is life sustained? You are transfixed by this question. And here you begin a process of studying the political economy, of analyzing your material conditions, and the conditions that you share with others.

5. A fifth wave is here. Through study, you become aware that life is sustained by gift giving, by mutual aid, by lending, and by informal exchanges. But you also are told—by the people who call you stupid, passionate, stubborn, or crazy—that the work of sustaining life is not really labor. You think: Perhaps this work will always be devalued, existing only to support the dominant economy of waged labor so that some people can make a lot of money, while those of us that sustain life continue to be un- or undercompensated. But, because you have survived, and you have this internal strength, this persistence, you think: Perhaps, there is another way. What if the work that sustains life can be valued, connected, and strengthened? You think: What if the work that sustains life is the economy we need, the economy of peace, of community, of cooperation? You know, as you know of your own survival, that this work has power.

6. A sixth wave arrives. You seek to learn more about the power of this work. The knowledge you seek has been hidden and devalued, like the knowledge that is embodied and visual, but you find it. You sense it in the arts, and around you, in the healers, the guides, and the caregivers. You learn that this idea—giving power and compensation to the labor that sustains life—is called the solidarity economy, and that it emerged from the global South in the 1990s, as economia solidária to describe economic practices and models which advance values of democracy, mutualism, cooperation, ecological sustainability, justice, and reciprocity. You learn that these economic practices can be visualized as follows:

Creation: Ideas and Resources

the commons: ecological and intellectual

free and open-source software and technology

community land trusts

skill shares

free schools

Production: How Things Are Made

worker cooperatives

producer cooperatives

non-profit artisan collectives

self-employment

labor unions

democratic employee stock ownership programs

local self-reliance

Transfer and Exchange: The Way We Share Goods and Services

barter networks

freeganism

sliding scale pricing

time banks

gifts

clothing swaps

tool shares

community currencies

fair trade

community supported agriculture

community supported kitchens

consumer (usually food) cooperatives

housing cooperatives and collectives

intentional communities

self-provisioning

non-profit buying clubs

Surplus Allocation: The Way We Create Economic Security

credit unions and community development credit unions

cooperative loan funds

rotating savings and credit associations

mutual aid societies

cooperative banks

community development banks

7. Another wave comes. You realize that the economy that art needs is one of the commons—of the solidarity economy—and that in order to sustain shared imagery, culture, communication without words, and embodied knowledge, the solidarity economy is critical. You begin to connect artmaking to this economy of care, knowing that your power, your survival, is connected to the survival of these other practices and people, well beyond the arts. You find community with these practices, and feel slightly less alone.

8. Another wave appears. You feel a tension between what you know are collective ways of meeting collective needs and what you are told is the horizon of possibility, that there is no alternative to being a starving artist, to doing household work without pay, to capitalism, in short. You learn that the tension between art and life, between a wage and a livelihood is as old as capitalism; it is capitalism. And you realize that you have been feeling, bodily, what so many people have felt for over 400 years. Only in that economic system—capitalism—does art confront the world as separate, as symbolic and non-reproductive; only with the rise of capitalism was art cast out of the world of daily life and rendered newly “useless.” You understand that the tension you feel arises from a 400-year old historical contradiction that must be held collectively and used to inform collective work; it is not a tension that can be resolved on a personal level.

9. The waves are stronger now. As you join in some collective work, you continue to learn about the history of organizing against profit for the few, against the exploitation of work that sustains life, against capitalism, and against the kind of art world capitalism bequeaths. You feel, with collective strength and experience, that another economy is possible in the arts, and beyond, because it already exists. Just as you have survived, this economy has survived, and is surviving.This economy of care, of cooperation, and of mutual aid is thriving, despite being marginalized and devalued. You continue to connect, grow, and strengthen solidarity economy practices and networks, and to learn about the ways that political power for the solidarity economy is growing internationally, in countries where cooperative economies are given more support than in the United States. You witness the wisdom in the collective work around you, the shared persistence, and shared strength. You begin to move through the world with awareness of this collective power, and begin to know that you are not alone. This awareness of collective power becomes part of your internal power that no one can take away from you.

10. A large wave comes, and you welcome it. You continue to transform, in community. You understand that the solidarity economy has always been led by Black, Indigenous, and people of color, especially women, nonbinary, and transpeople. You explore the parts of you that are held up by dominant culture, and the parts that are not. You explore how you show up in groups, and you see how this ongoing work makes deep connections across differences possible. When you can, you take resources from the dominant economy and put them into alternative and post-capitalist economies so that they can continue to grow. You divest from exploitation and invest in the work that sustains life. You join the worker cooperatives, credit unions, land trusts, community gardens, and initiatives that extend well beyond the arts. You address and move through the interpersonal difficulties of collective work, of the pain of trying to be less alone, and you strengthen the collective capacity within you. How do you feel?

11. The waves are strong, but so are you. When the economy collapses, as it has and will, again and again, under capitalism, you know how to survive. You might lose your job, but you cannot lose your identity, as no one can take this—your creativity, your collective strength, your gift economies—away from you. You know that the solidarity economy, with your deep relationships of care, your mutual aid networks, your community currencies, your barter networks, and your community gardens, land trusts, and cooperatives will sustain themselves, as they always have. You know that, despite being told that you are stupid, passionate, stubborn, or crazy, you have collective strength with you. You are practicing a powerful economy of care, together. You have all survived, are all working together. This is your internal power that no one can take away from any of you. And you continue to thrive. How do you feel?

12. A final wave appears. One day, someone acknowledges your strength, and you smile, and say something like: I know, in the depths of my being, that I help sustain life, and that, as an artist, I am able to let myself feel, and to be present with those feelings. I am in control of my labor. I structure desire and imagination. I create space for emotionally open responses. I make memorable symbols. I help to solidify memories and histories. I speak truth to power. I can communicate without words. I use the powers of fiction and play to question norms and reveal possibility. I connect communities—geographic, identity-based, and professional. How do you feel?

“My identity is not tied to my job.

No one can take my livelihood away from me.”

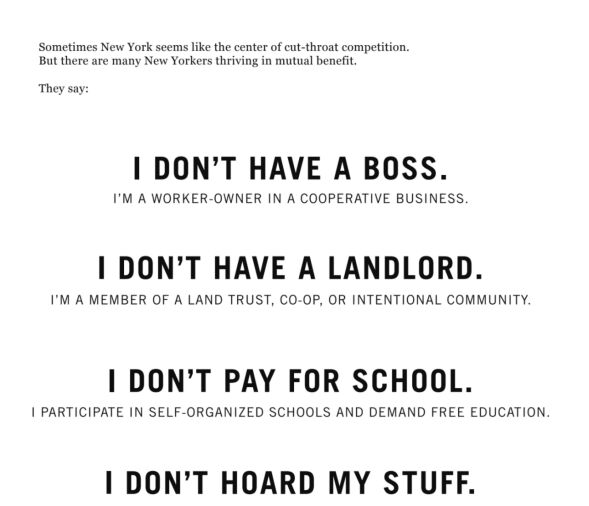

“I don’t have a boss.

I’m a worker-owner in a cooperative business.”

“I don’t have a landlord.

I’m a member of a housing co-op or intentional community.”

“I don’t need to buy more stuff.

I take part in tool-shares, barter clubs, and clothing swaps.”

“I don’t want my bank to make profit for the sake of profit.

I joined a credit union, so my money stays in the community.”

“I know where my food came from.

I’m a member of a food co-op, CSA, and community garden.”

“I don’t call the cops.

I’m a member of a community safety group for transformative justice.”

13. You sense more waves, but the water is calm again. What is here? Dream into it. What waves do you sense around you? Take in the feelings, smells, tastes. How do you feel? I invite you to keep dreaming.

Editor's note. This is a pre-publication to our newly printed issue, Trigger#5: Energy, which is the FUTURES edition of 2023 (out in november 2023). In that issue, the editors develop a collaborative contribution 'Dreaming Up Collective Energies' in relation to Caroline Woolard's manifesto. This manifesto calls for a new (arts) world with a focus on alternative production modes in the arts, solidarity, collective values and political economy. Our affiliation with Caroline Woolard's working practice is built around our common position - as co-editors of that issue - that a 'solidarity economy' is a necessary precondition to revision the relation between photography and energy. For more on Woolard's practice, check out the publication Art, Engagement, Economy. The Working Practice of Caroline Woolard (Onomatopee: 2020).