Technology on Loop: An alternative history of algorithms through Double Exposures

In Africa, as in most parts of the dispossessed, the camera arrives as part of the colonial paraphernalia, together with the gun and the bible.Yvonne Vera quoted by Teju Cole, 'When The Camera Was A Weapon of Imperialism (And Still Is)',https://www.nytimes.com/2019/0...

Yaa Addae

16 nov. 2023 • 11 min

When I first wrote about Ethel Tawe’s practice in 2021, I was drawn to her shadow play: video diaries of the shapes her movement created when placed in the path of rays of light. Shared on Instagram, these were more intimate explorations that she let us into than a curated body of work. But looking back, even then, she was interested in what can be made out in the darkness.

In creating a photograph, light enters the camera through a shutter, and in doing so, imprints a lasting impression upon film to create a representation of reality – or so we believe. With Double Exposures, a collection of collages, video work, and photographic reprints together with an interactive installation, Tawe asks us to look again through the lens of context. The multidisciplinary artist, curator, and time traveller’s latest project is a continuation of her Camptian‘Camptian’ refers to Tina Campt, Black feminist theorist of visual culture and contemporary art. practice of listening to images – sitting alongside her parallel experiments with Image Frequency Modulation, ‘an ongoing iterated body of work investigating the sonic, visual and haptic frequencies of images.’

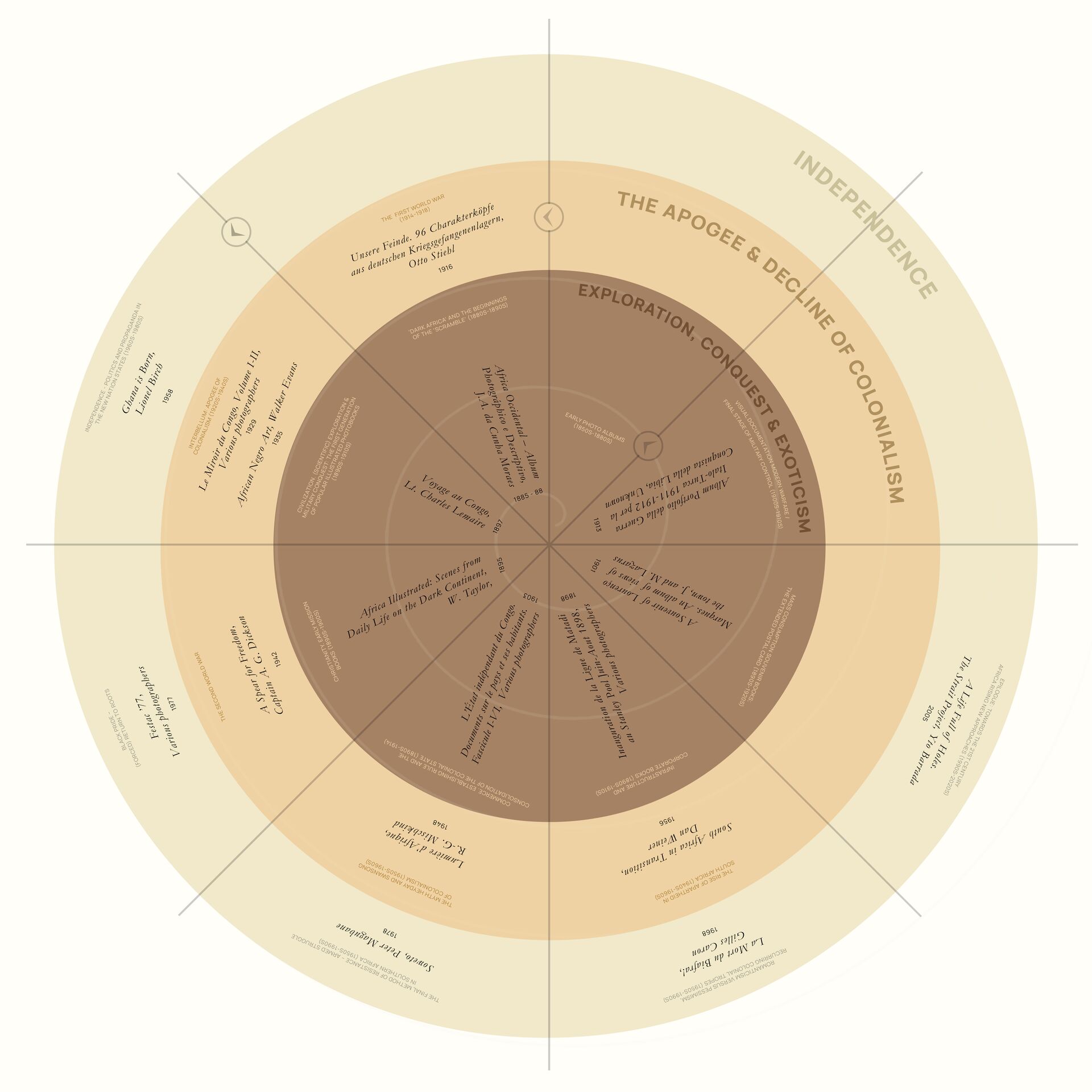

Time-spiral: An Annotated Bibliography (2023)

Data visualisation of four key eras in the history of photobooks, examining their circulation and evolution through the bending of a timeline. A selection of exemplary book titles per era is provided as an introduction to typical practices of the time. This bibliography is a work-in-progress and can be delved into via africainthephotobook.com

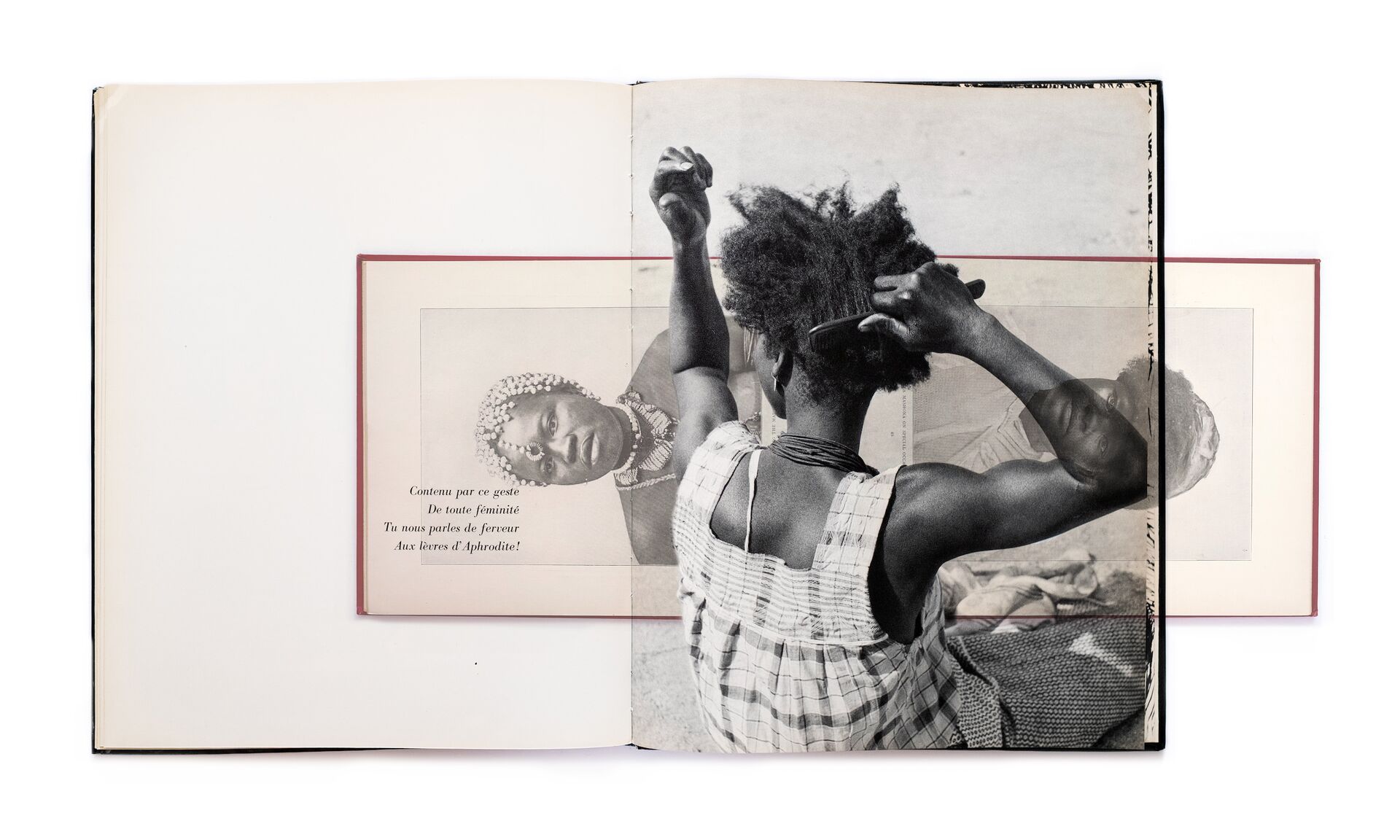

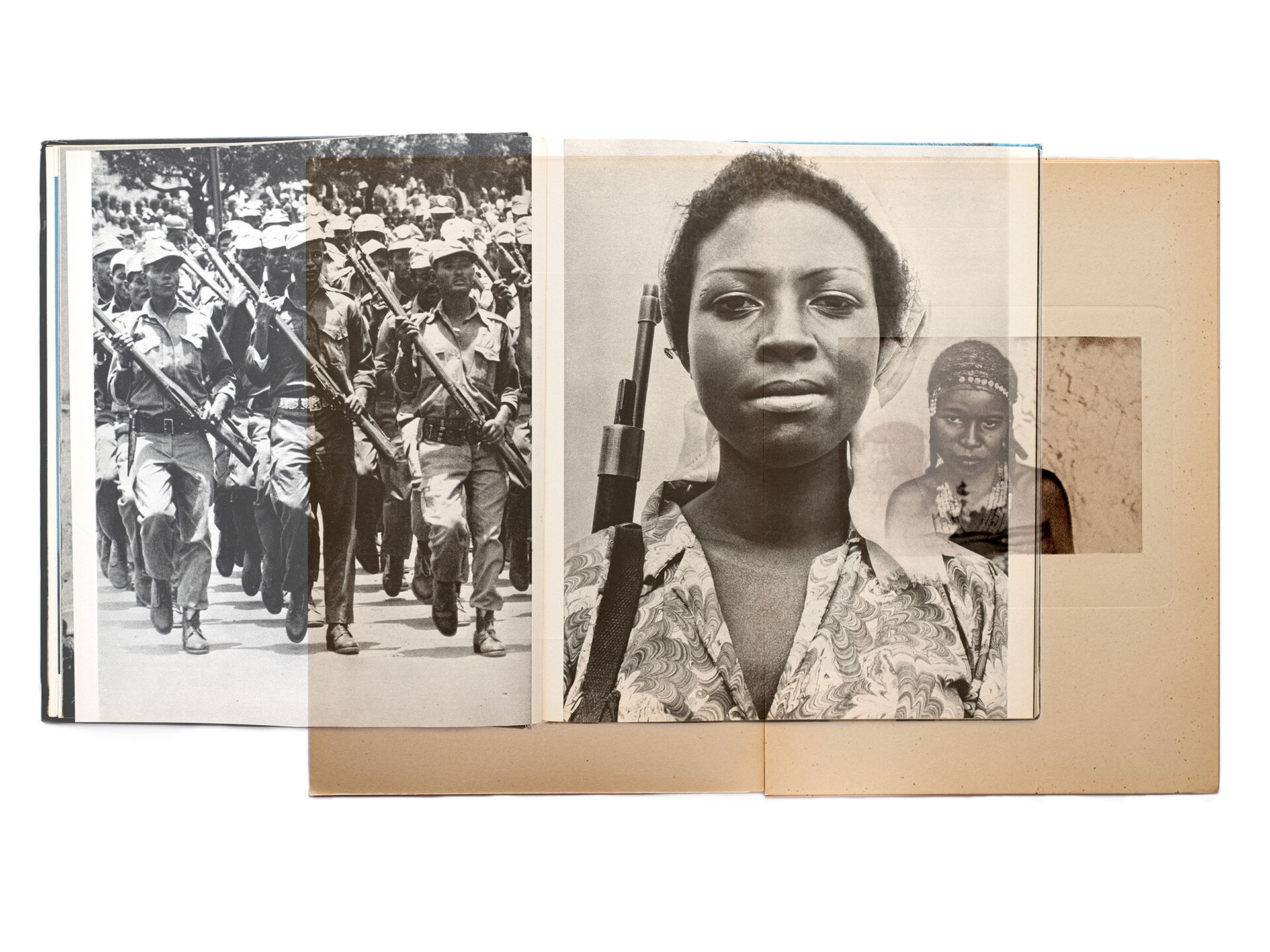

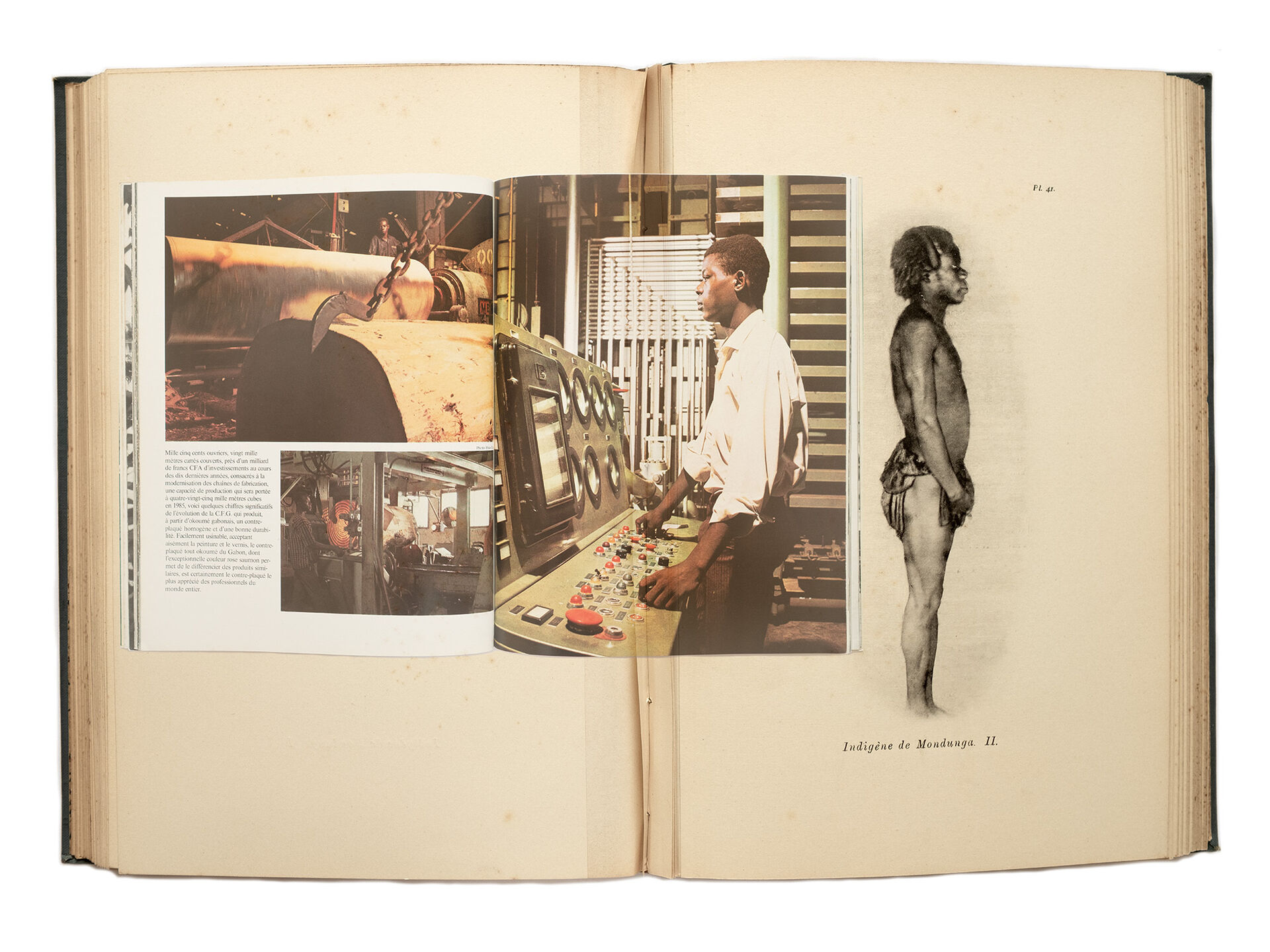

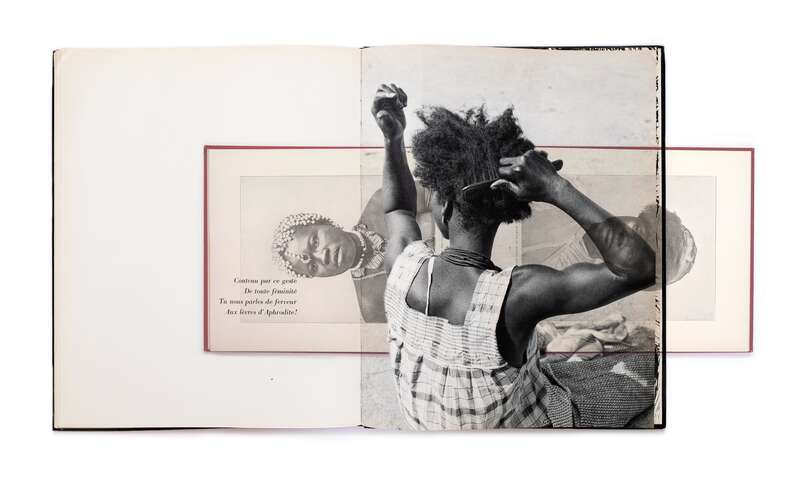

In Double Exposures, Tawe turns to the archive, presenting visual strategies for seeing anew. Since 2015, photographer and photo historian Ben Krewinkel has been documenting the changing visual representations of Africa as expressed through photobooks from as early as 1885 — the year of the Berlin Conference. After Tawe and Krewinkel spent months together diving deeper into this collection, Double Exposures came about as a critical ‘reframing and extrapolation’ of the way these books are engaged with. At PhotoIreland 2023, viewers were ushered into this presentation by Time Spiral: An Annotated Bibliography – a visual bending of time that layers the evolution of the photobook as a medium with the expansion of colonialism, temporally grounding the viewer before illuminating the ways that these histories still show up today. Travel between the past and present recurs throughout the work, evident in the three collages that the collection is centred around. Double Exposures I, II, and II feature overlapping images in which time collapses to create what Tawe describes as ‘unintended continuums that exist in the process of postcolonial self-determination.’Ethel Tawe, Double Exposures, https://nataal.com/double-expo.... Here we see the blurring of paired photographs: a Gabonese engineer controlling a machine at a factory from a 1970 photobook with a taxonomical image of a Black man from the nineteenth century, the meeting of a woman captured by a Portuguese ethnographic catalogue in 1934 and that of an Angolan woman holding a gun in Am Horn Von Afrika (1983), and lastly, yet another ethnographic image of a woman adorned by an intricate beaded headpiece contrasted with a young girl combing her hair. When these images are taken out of order, new readings occur, and in doing so, Tawe alludes to the importance of sequencing strategies within photobooks.

Panel from Con(text), triptych, 2023 © Ethel Tawe, Ben Krewinkel.

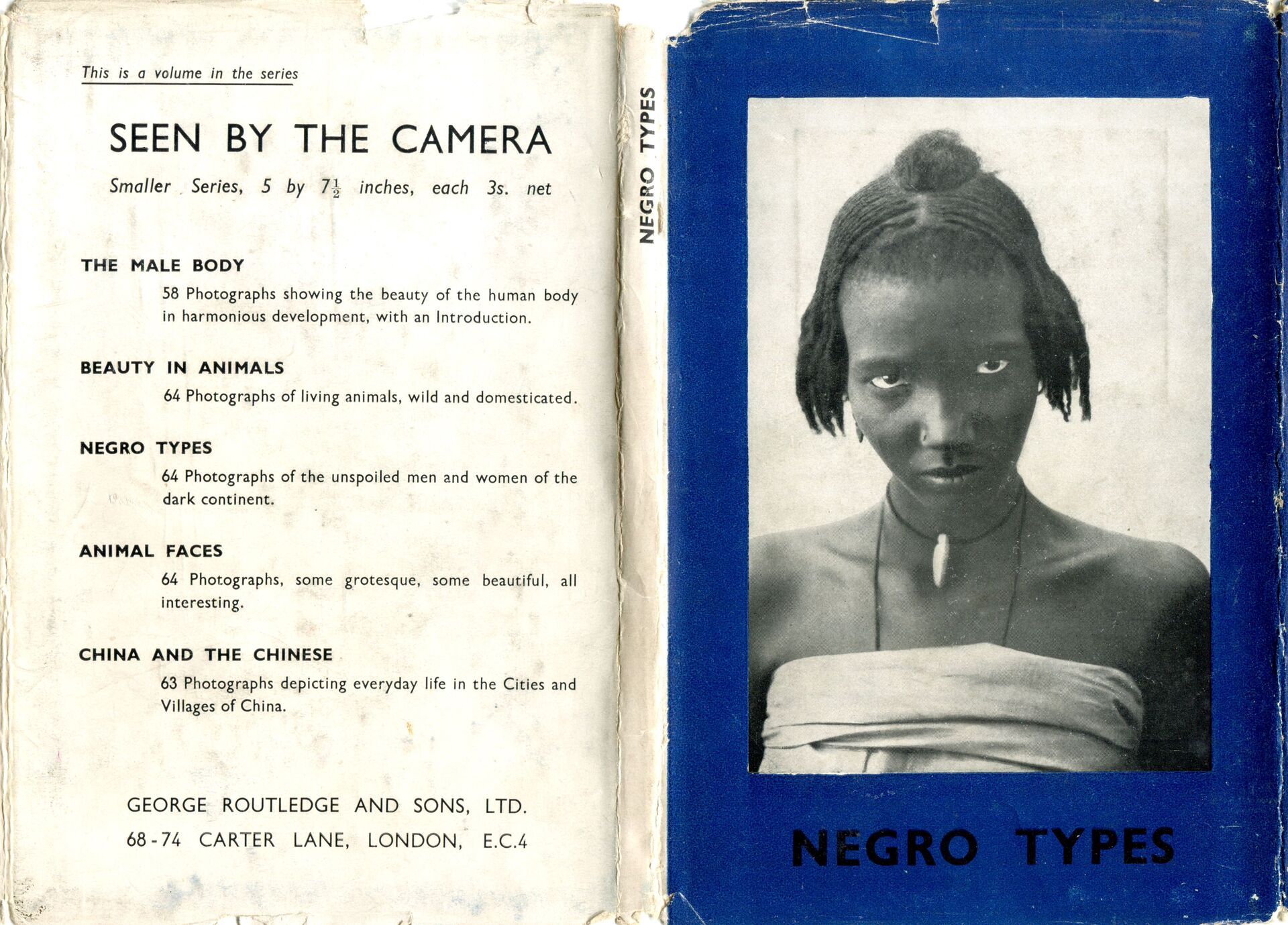

Con[text] dissects the anatomy and evolution of African photobooks within the framework of a hyperpresent subject: beautification. The triptych displays distinct and shifting perspectives on a timeline, from the height of colonial conquest, independence era, and into a contemporary conversation. It calls for increased attention to the text (the context) of photobooks and their knowledge producers.

The opening pages of colonial photobooks often begin with exterior shots of landscapes and progress to colonial settlements along the coast before venturing into the interior. The sequence of images and their placement in a photobook can guide viewers through a story or idea, informing fictitious visions of undiscovered terrain. This narrative trajectory sometimes resembled ‘the heart of darkness’, mirroring the journey of explorers into Africa’s interior, showcasing the conquest of the land, and entangling domination with the physical landscape.

To see was to own – or at least stake claim, highlighting a gaze of extraction. This was particularly true of smaller colonial powers such as Belgium, where King Leopold utilised the photobook as a ploy to gain investment for his private colony, and Portugal, which was known for producing some of the most aesthetically pleasing books in terms of form due to a need to prove the range of their presence on the continent. ‘Although the Portuguese were the first Europeans to stay in African coastal place,at the time of the Berlin Conference they were one of the weakest nations in Europe. These books were really meant to gain support in Portugal, but also outside Portugal for the Portuguese colonial endeavour,’ Krewinkel explains. ‘In Belgium, on one hand, you saw photobooks, articles in magazines and newspapers against Leopold, and then on the other hand, advocates of Leopold produced books to show that they were doing the right thing – showing civilisation missions and other propaganda. In the end, Leopold had to hand over his private colony to the Belgians, and so from 1908, a new set of books were produced to sell the colony to the Belgian people, because the Belgians now had to pay for this colony.’

These photobooks evolved over time in their messaging, with one version often shared in Europe and another in Africa. This strategy of double circulation allowed for the multiplicity of truths: in one context, Africans were friends, no longer ‘savages’ and now ‘worthy’ of standing alongside European soldiers to defend their nations during World War II, and in another context, Africans were European themselves, selling a dream of citizenship and belonging.

In our conversation, Krewinkel pointed me towards one such example: A Spear for Freedom, photographed by Captain A. G. Dickson and published by the H.M. Stationery Office in 1942. In the version intended for English audiences, African soldiers (also known as Askari) are shown as brothers in arms, fighting alongside the British to defeat the threat of fascism. This reality was one in which Africans were no longer enemies, indicative of an attempt to change public perception. In the version intended for an African audience, this war promised success and wealth. Featuring captions in English, Swahili, and two other African languages, the images accompanied war films that were screened across Kenya and Tanzania as part of recruitment efforts.

In this way, photobooks function as early algorithms – sets of instructions based on data to create specific outcomes. Just as algorithms sift through vast amounts of data to curate and select a specific content for users, the creators of colonial photobooks curated and selected photographs to construct a particular ‘truth’. They chose which images to include, their sequence, and the context in which they appeared, shaping the viewer’s experience and reinforcing narratives of domination.

Considering the camera’s role as both witness and accomplice to colonialism, I’m reminded of Dark Matter Objects: Technologies of Capture and Things that Can’t Be Held by Neta Bomani. The film juxtaposes the master/slave dynamic of control with the foundational architecture of hardware, articulating how ‘technology is all bound up with slavery’.Neta Bomani, Dark Matter Objects: Technologies of Capture and Things that Can’t Be Held, https://netabomani.com/darkmatter/. In the film, a page of the accompanying zine is narrated out loud:

Shoot the footage

Capture the audio

Record the masters

Switch the tapes

Manipulate the code

Upload the files

Stow the memory

Export the assets

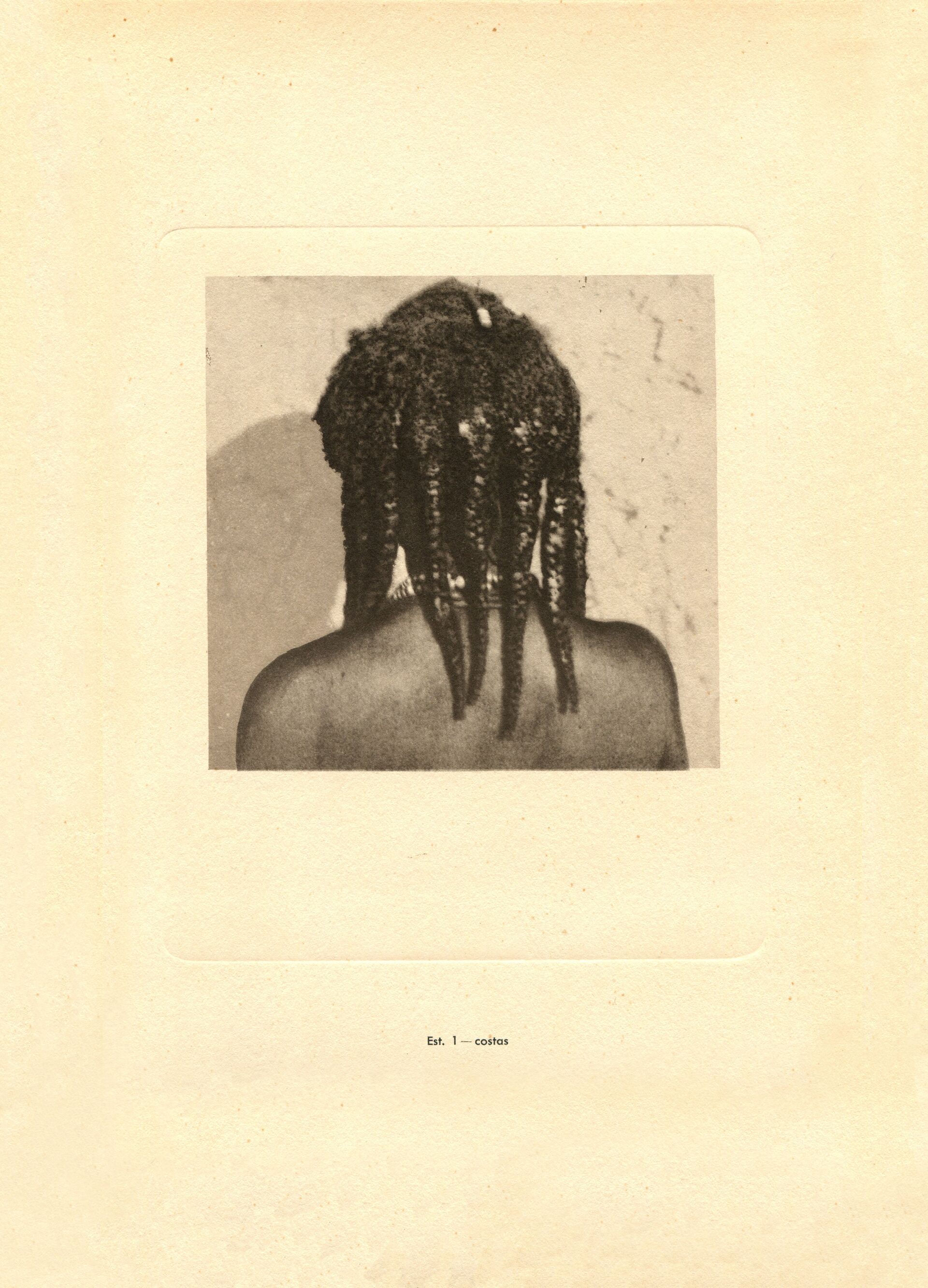

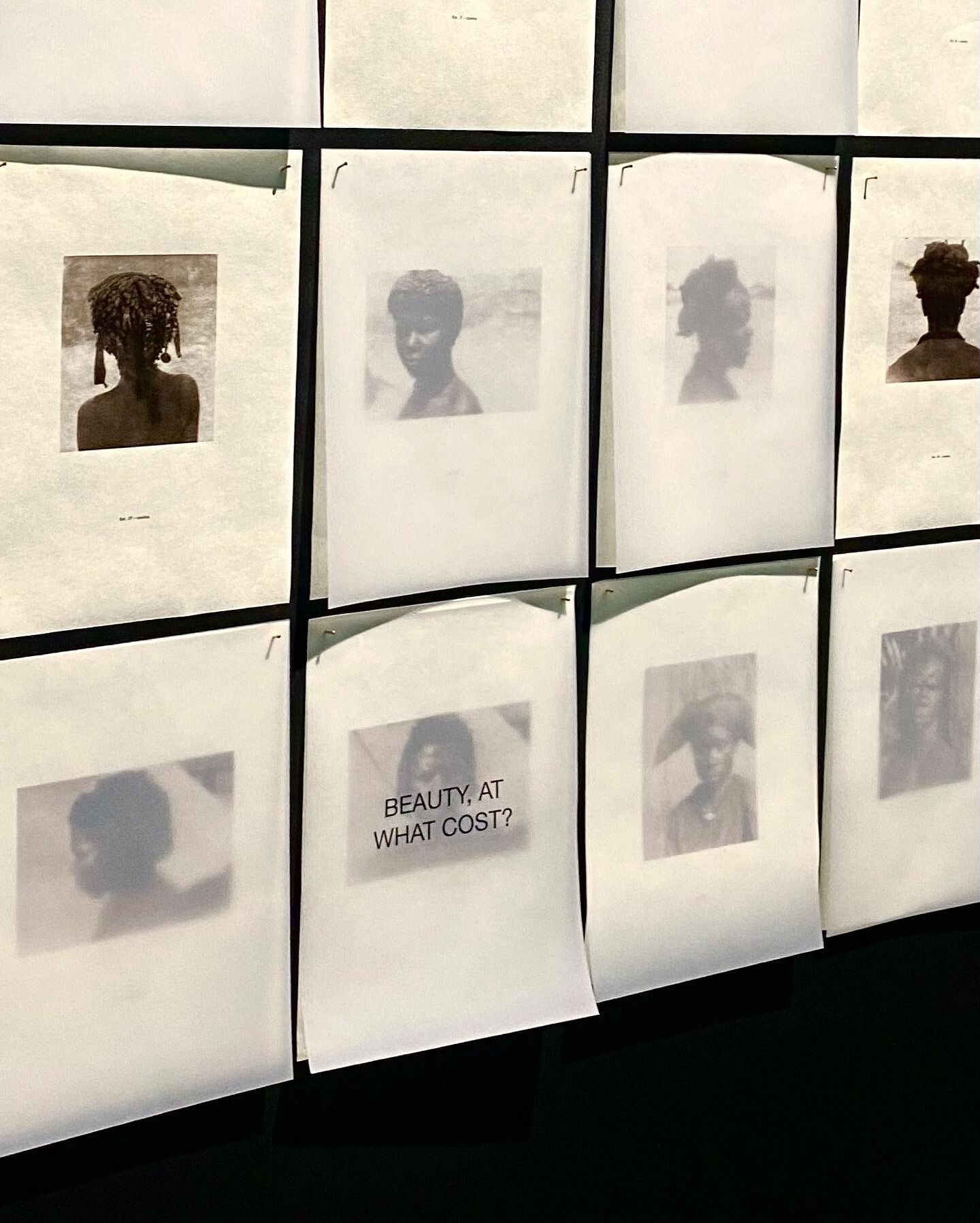

Opacity, interactive display, 2023 © Ethel Tawe, Ben Krewinkel.Etnografia Angolana (1933) portfolio book by Portuguese engineer and amateur anthropologist Fernando Mouta.

The photobook, too, is complicit in this inherent truth: technology, in the Western imagination, has long been a means of innovating violence, sold as a marker of human development. Given this correlation, I return to Ethel’s intention with Double Exposures: What does it mean to ‘ask questions with care’ when encountering an archive programmed to deceive? What would it look like to read between the lines, rewrite the code, and break the patterns that we’ve inherited?

In Opacity, Tawe uses forty-eight replicated plates in their original sequence from a portfolio book on people of the Malange and Lunda region of Angola, filtered by transparent sheets, to confront the viewer with questions that resist the extraction required of the colonial gaze:

What is my name?

What are we looking at?

Can visibility render invisibility?

Who is omitted?

Beauty, at what cost?

What do we learn from this ‘study’?

Are you tired of the spectacle?

Opacity, interactive display, 2023 © Ethel Tawe, Ben Krewinkel.

Still from Typing… , single-channel video, 2023 © Ethel Tawe.Footage of a Mangbetu woman's gaze in Belgian Congo 1940s travelogue film made by Paul L. Hoefler, who also co-authored the exploitation film and book Africa Speaks! (1930)

The tension is again clear in Typing… , looped footage of a Mangbetu queen being documented and categorised, much like an artifact in a museum. Despite the one-sided purpose of the recording, she looks back, complicating the camera’s attempt to package her as a nameless character. This is what Saidiya Hartman speaks to in 'Venus in Two Acts'. In this context, she says, the archive assumes a haunting role, akin to a death sentence or a tomb. It offers but a few lines, almost as an afterthought, on the lives of the individuals it purports to represent. These lives, once stripped of their freedom, can hardly be recaptured as they were in their unrestrained state. The task at hand is one of ‘listening for the unsaid, translating misconstrued words, and refashioning disfigured lives – and intent on achieving an impossible goal: redressing the violence that produced numbers, ciphers, and fragments of discourse, which is as close as we come to a biography of the captive and the enslaved’,Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14, muse.jhu.edu/article/241115. she writes. This is the care that Tawe practices within her work – a considered interrogation of the photobook, and by extension, the technology of photography and its ability to construct reality.

What does this have to teach us about today? The television was invented in 1927, and less than twenty years later, approximately 8,000 US households had TV sets. By 1960, this figure reached 45.7 million, demonstrating steady growth over thirty years. Almost a century after the arrival of TV, OpenAI introduced ChatGPT to the world. Launched in November 2022, it had gained over 100 million monthly users by January 2023 and soon after surpassed a billion monthly page visits, cementing its position as the fastest-growing application in history. We are now experiencing what is being described as an AI explosion, although this is not the first time that we’ve encountered algorithmically generated information.

Much like the visual data that was curated and selected to shape Western perception of Africa, heavily flawed datasets still largely shape what is being described as the future of knowledge-production. For example, much of the predictive policing that supports the work of the ‘justice’ system within the US relies on patterns that equate blackness with criminality – an association that echoes the logic of the transatlantic slave trade. In 2017, artist-technologist Mimi Onuoha defined algorithmic violence as ‘violence that an algorithm or automated decision-making system inflicts by preventing people from meeting their basic needs. . . like other forms of violence, algorithmic violence stretches to encompass everything from micro occurrences to life-altering realities.’ This data trauma has roots in the colonial archive, enmeshed with the ways that innovation is continually used as a method of perfecting structural harm. ‘I’ve been revisiting the work of Dr. Safiya Noble and thinking about how these search engines today autocomplete results of hypersexualized Black women, as one example. That is not much different from what these photo books were doing. Why has that remained? According to Dr. Noble, Google’s first digitization project involved mass scanning of books at libraries to build what she believes were the earliest datasets for machine learning and search engines. This is a direct extension of colonial algorithms’, Tawe says.

As Double Exposures suggests, we’ve been here before and this technology is not new. The loop continues. Central to this violence is the colonial obsession with categorisation. To be legible to an algorithm, one must fit neatly within a set of characteristics. We see this today with ‘for you’ pages – curated feeds based on previous decisions we’ve made that now define the information we’re provided with. While seemingly benign, this process of predetermination makes way for lazy, harmful thinking – mental shortcuts programmed on the back of years of violence that have not been interrogated. Recognizing that this has happened before is the first step to beginning to question what ‘data’ underlies the dominant truths of today. Legacy Russel’s Glitch Feminism reminds us that there is a world beyond this logic. In the Glitch Manifesto, she suggests that we might embrace ‘the causality of “error” . . . by acknowledging that an error in a social system that has already been disturbed by economic, racial, social, sexual, and cultural stratification and the imperialist wrecking-ball of globalisation – processes that continue to enact violence on all bodies – may not, in fact, be an error at all, but rather a much-needed erratum. This glitch is a correction to the “machine”, and, in turn, a positive departure.’Legacy Russel, ‘Digital Dualism and The Glitch Feminism Manifesto’, The Society Pages, 10 December 2012, https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/12/10/digital-dualism-and-the-glitch-feminism-manifesto/.

By considering the context that Tawe and Krewinkel illuminate within Double Exposures, we are better placed to reprogram the algorithmic violence that lies at the foundation of knowledge production. From there, we can ask: what alternative technologies exist? Ones rooted within intentional rupturing, as demonstrated by the exposé of Double Exposures I, II, and III, by refusals like that of the Mangbetu queen who questions the camera in Typing. . ., by care like the strategy of obscuring the anthropological gaze in Opacity.

Double exposure, curated by Ben Krewinkel and Ethel Ruth Tawe, was first exhibited in PhotoIreland Festival 2023: R/evolutions.