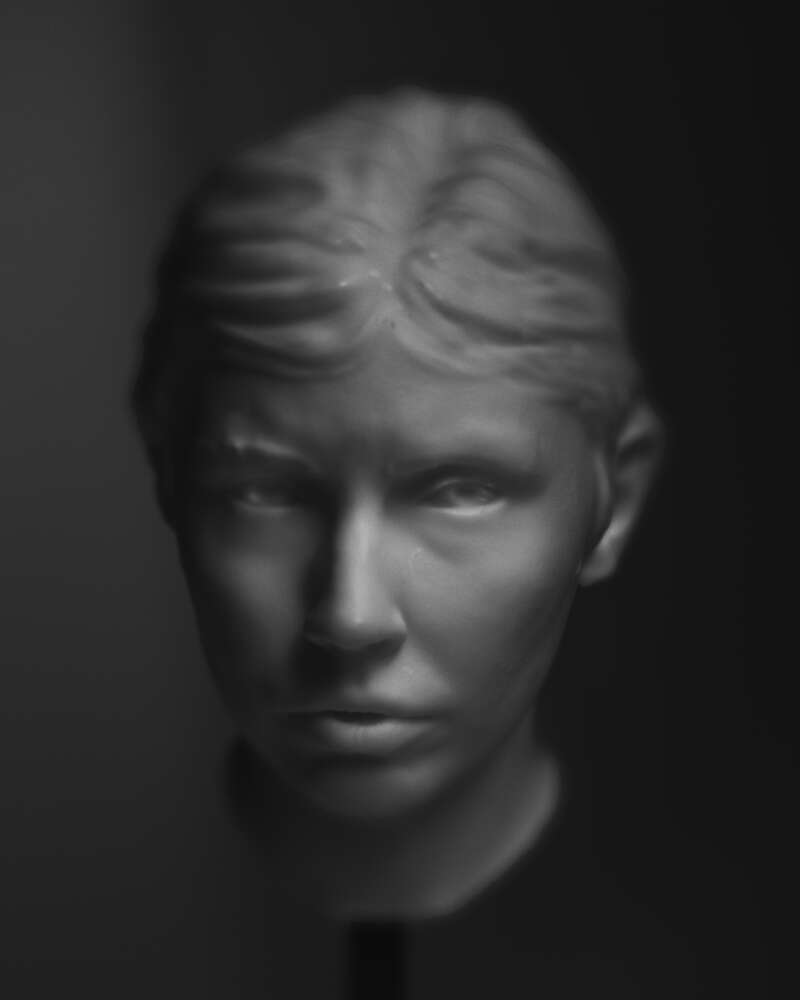

Hoda Afshar, from the series Agonistes, 2020.

Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery

Struggle, Authenticity and Visibility

'Struggle, Authenticity and Visibility' is part of Trigger #2: Uncertaintypublished in December 2020 by FOMU and FW:Books which deals with the role of the speculative in documentary making. This essay accompanies the artist contribution Agonistes by Hoda Afshar that can be found here.

Wim Vandekerckhove

19 feb. 2021 • 9 min

Since 1999, I have been involved in interdisciplinary research on whistleblowing – how people raise concerns about wrongdoing, how those concerns are neglected, how people respond by escalating them and how organisations become machinery for retaliating against whistleblowers. With that extensive background in research, I find the title of Hoda Afshar’s work is spot on: Agonistes, or ‘those who struggle’. Afshar documents the struggle of whistleblowers. Her work is a combination of a video in which whistleblowers narrate their journeys and photographs of whistleblowers as statues that represent their narratives without sound. In so doing, she s the ambivalence of whistleblowing.

Her photographs of whistleblowers’ sculptured heads remind me of Greek Hellenistic sculptures. One would think that statues are for military heroes, but the Hellenistic as well as Hoda’s bust sculptures are of citizens. In scholarship, whistleblowing is discussed as a form of civil disobedience. Whistleblowers are often portrayed as heroes, villains or freaks, but in any case, they’re always presented as extraordinary people. Yet, both Hellenistic head sculptures and Afshar’s photos could be of anyone. The analogy between Afshar’s depictions and the sculptures of ancient Greece, where we believe democracy has its roots, goes even further. The French philosopher Michel Foucault reminded us of a particular way in ancient Greece of speaking truth – parrhesia, or frank speaking – that lies at the core of all democracy. Parrhesia is a mode of truth-speaking that isn’t technically sophisticated. Hence, it’s not the truth of a teacher. The frank truth of parrhesia is also not part of a bigger agenda, nor is it spoken on behalf of some higher purpose. Hence, it’s not the truth of a prophet. Furthermore, the frank truth isn’t abstract but concrete. It’s the kind of truth whistleblowers expose: simple, factual descriptions of malpractice.

Like whistleblowing, parrhesia is dangerous. In ancient Greece, the parrhesiastes, like whistleblowers today, told it like it was and risked their lives for doing so. Perhaps that is why a number of academic scholars (myself included) have found the figure of parrhesiastes so appealing to understand whistleblowing. The courage of whistleblowers is truly impressive and the figure of the parrhesiastes represents that, as do Afshar’s photographs of sculptures of whistleblowers. Their subjects’ courage makes them deserving of a statue. Yet, Afshar does not call them ‘parrhesiastes’. Instead, she names her work Agonistes: ‘those who struggle’. Is she suggesting that what makes someone a whistleblower is not the frank truth they’re speaking but the struggle they undertake? That is a fascinating idea, and I want to pursue it in what I write here. Afshar’s conceptualisation of whistleblowing as struggle resonates with a social science scholarship that approaches whistleblowing as process and as ambiguity.

In the video, Afshar synchronises the whistleblowers’ narratives. These are not stories of brave and clear decisions. Rather, we hear how whistleblowing is an escalation of considerations, gestures, doubts and attempts to find someone who wants to listen. The courage of these people doesn’t lie in one single decision. Instead, their courage lies in not giving up, almost in their naivety rather than their agency. Casting whistleblowers as heroic parrhesiastes is akin to asserting an existentialist philosophy in which humans have full agency and, hence, full responsibility. From that perspective, a whistleblower would only be a hero if and to the extent that they make the decision to be a whistleblower wholly and at once, out of free will. Such a hubris does not breathe from Afshar’s work. Hers is more of a modest existentialism that can be found in the work of Camus. In particular, when writing this, I have l’EtrangerAlbert Camus, L’Etranger (Paris: Gallimard, 1942). It was first published in English in 1946 as The Stranger (London: Hamish Hamilton).in mind. Camus’s reality is one that bulldozes you. If the moment of responsibility is deciding what to do in the situation you are in, then the challenge is not necessarily having the courage to make the decisions that need to be made. Rather, for Camus, the problem was that the only insight you have is hindsight. In l’Etranger, the main character has no clue what he’s getting involved in, yet he maintains moral agency despite his inability to predict the consequences of his actions. Thus, in Afshar’s work, we hear the whistleblowers recounting their decisions about what to do only to find out what it was they then got themselves into – not once but a number of times.

We can also look at law and its institutions in both Camus and whistleblowing. Legislation protecting whistleblowers has boomed since 2010. However, Australia, where Afshar works and which is the context of Agonistes, was the second nation after the United States to pass whistleblowing legislation in the early 1990s – more precisely, the 1990 interim provisions in Queensland, the 1993 South Australian Whistleblowers Protection Act and, in 1994, legislation in Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Australia is a federal state, so the timing and scope of legislation tends to vary depending on particular jurisdictions, but the point is that Australians have been at this for a while now. Yet, it apparently remains difficult for whistleblowers to find justice through the law and its courts. My latest research looked at 600 whistleblowing cases heard at employment tribunals in England and Wales.Laura William and Wim Vandekerckhove, Making Whistleblowing Work for Society (London: APPG for Whistleblowing, 2020). doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24559.25761 We found that only about 12% of whistlerblowers won their cases in court. But what does ‘winning’ mean? It takes two to four years, and there are cases in which the judge acknowledges that the disclosure was in the public interest – and, therefore, that the whistleblowing was legitimate – but fails to accept that the whistleblowing was the reason why the whistleblower was dismissed. As in Camus’s work, whistleblowers can end up in institutional processes that duly go through their procedures and scripts, quickly losing sight of the human dramas that triggered them. Indeed, human authenticity stands in contrast to organisational and legal realities.

That contrast is a central theme in existentialist philosophy. I believe it’s appropriate to view whistleblowing through that lens. The whistleblower’s journey can be seen as a constant morphing of absurdities. Here’s how such a journey could unfold:

- the absurdity of wrongdoing – human rights breaches or massive frauds – in organisations that have espoused values of respect, safety and security;

- the absurdity that others do not seem to notice that wrongdoing;

- the absurdity that your manager doesn’t want to hear what worries you, nor do top managers or anyone else, not even regulators;

- the absurdity of falling from grace with your employer while you’re practicing what’s stated in the corporate values, what’s in the code of conduct and according to official policy;

- the absurdity of being hated for speaking the truth and seeing others rewarded for sticking to lies;

- the absurdity of getting no vindication for any of this through the institutions designed to do just that, i.e., alternative conflict resolution in the workplace or whistleblowing legislation and courts; and

- the absurdity of trying to save democracy by revealing where a democracy is no longer meaningfully democratic.

For existentialists, the ethical question – the challenge of responsibility – is to be authentic in the face of absurdity. Whistleblower stories are fascinating accounts of how reality can be a sequence of morphing absurdities. The above sequence isn’t untypical of what whistleblowers go through. In a previous research project, we mapped the trajectories of 1,000 whistleblowers, coding who they’d raised their concerns with and in what sequence.Wim Vandekerckhove, Cathy James and Francesca West, Whistleblowing: The Inside Story – A Study of the Experiences of 1,000 Whistleblowers. (London: Public Concern at Work/University of Greenwich, 2013). https://gala.gre.ac.uk/id/eprint/10296/ Some clear patterns emerged during the analysis. One was that whistleblowers don’t make a choice between voicing their concern to someone inside or making a disclosure outside the organisation. They mainly stay inside. We found that the first time whistleblowers voice their concern, 93% do so within their organisation; the second time, 77% stay inside and 23% go outside; the third time, the inside-outside ratio is 64% to 36%; even the fourth time, it’s still roughly 50/50. That’s a clear indication that whistleblowers typically aren’t reckless protesters or disloyal workers; they’re not out to damage reputations. Instead, it seems they’re discovering the real depths of organisational absurdity as their journey protracts.

As their stories unfold, we can also see just how challenging their quests for authenticity become. Another pattern we found in our research was that, typically, whistleblowers report wrongdoing in a sequence that entails a search for impartiality. Every time they voice their concerns, whistleblowers do so with someone further away from the wrongdoing and in possession of a more specific mandate to step in. This indicates that on their journey, whistleblowers try to be authentic by searching for authenticity in others. Listening to the whistleblowers in Afshar’s video, I see that their struggle is a search for someone who will listen. First someone close by – a bystander, a colleague, the wrongdoers themselves – and then someone with authority, like managers, within the organisation. After that, they search for someone with a specialised function to stop wrongdoing – auditors, regulators, police – and finally, perhaps, they go to a journalist because no one else stood up in the face of all that absurdity – no one else listened.

Afshar’s video and photographs also point to the struggle as an ambiguity, which whistleblowing is. In her video, she shows close-ups of the mouths, ears and eyes of the whistleblowers but never their full faces. She shows parts of the body that can identify individuals but never gives their identities away. This is how Afshar visualises whistleblowers’ struggles with confidentiality: making them visible while keeping them invisible. The whistleblower speaks truth but hesitates to be seen as a speaker of truth, hesitates to step onto the pedestal and make a statue of themselves. Research led by Griffith University in AustraliaAJ Brown (ed), Clean as a Whistle. Key Findings and Actions. (Brisbane: Griffith University, 2019). http://www.whistlingwhiletheywork.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Clean-as-a-whistle_A-five-step-guide-to-better-whistleblowing-policy_Key-findings-and-actions-WWTW2-August-2019.pdf has shown that one of the most important reasons people give for stepping away from whistleblowing is that they don’t trust hotlines or other reporting channels to keep their identity confidential. Those who investigate whistleblower reports also acknowledge that the more difficult it is to keep a whistleblower’s identity confidential, the more likely it is that the whistleblower will suffer retaliation. So how do you get people to listen without revealing yourself as the speaker? That, too, is what whistleblower stories are narratives of; or, at least, they’re narratives of the trial and error of doing that. The photographs of the sculptured heads perhaps show the next phase when we obtain representations of whistleblowers but are compelled to wonder what has happened to them – where’s the sparkle in their eyes? Who are they, really? And why are ordinary people made into statues?

Hence, in Agonistes, Afshar shows us whistleblowing as two struggles: the existentialist struggle to be authentic in a context of morphing absurdity and the authentic struggle of making

visible without becoming visible.