Sorry for the War © Peter van Agtmael | Magnum Photos

The border had closed at midnight after Hungarian officials hastily erected a barbed-wire fence, blocking thousands of Syrian, Iraqi, and Afghan refugees from entering. The refugees camped out, protested, and hoped the border would reopen. Hungarian police lined the fence and beamed their flashlights at the cameras of photographers attempting to document the scene. It quickly became clear that the crossing was unlikely to reopen and the next morning most of the refugees pivoted towards Croatia, as the country announced they would facilitate passage through. There were clashes the next day on the Hungarian border, as Hungarian riot police teargassed dozens of migrants who rushed the fence. Horgos. Serbia. 2015.

Sorry for the Dissonances

Sahar Khraibani

29 jul. 2022 • 8 min

To look at photographs that record the consequences of imperialism and its subsequent military conflict is essentially to look at ghosts: people, places and moments past, locked in a split second and memorialized in a photograph. In Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, sociologist Avery Gordon writes: ‘We are haunted by those who suddenly become visible. They are unfinished business. Ghosts remind us of past injustices and the need for future reckoning. History is haunted; we are haunted.’1. Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 23.

A photograph, very much like a haunting, always registers the harm inflicted, or the loss sustained, by violence done in the past or being done in the present, and it is for this reason a crucial historical record. But haunting, unlike other kinds of trauma and apparitions, is distinctive for producing, as Gordon calls it, a ‘something-to-be-done’. Similarly, we can consider photographs as hauntings that are capable of galvanizing societal and political change, ‘a something-to-be-done’. An example of this is the photo of the drowned body of the three-year-old Kurdish-Syrian boy Alan Kurdi, which sparked collective action leading to Europe momentarily opening its borders for refugees.

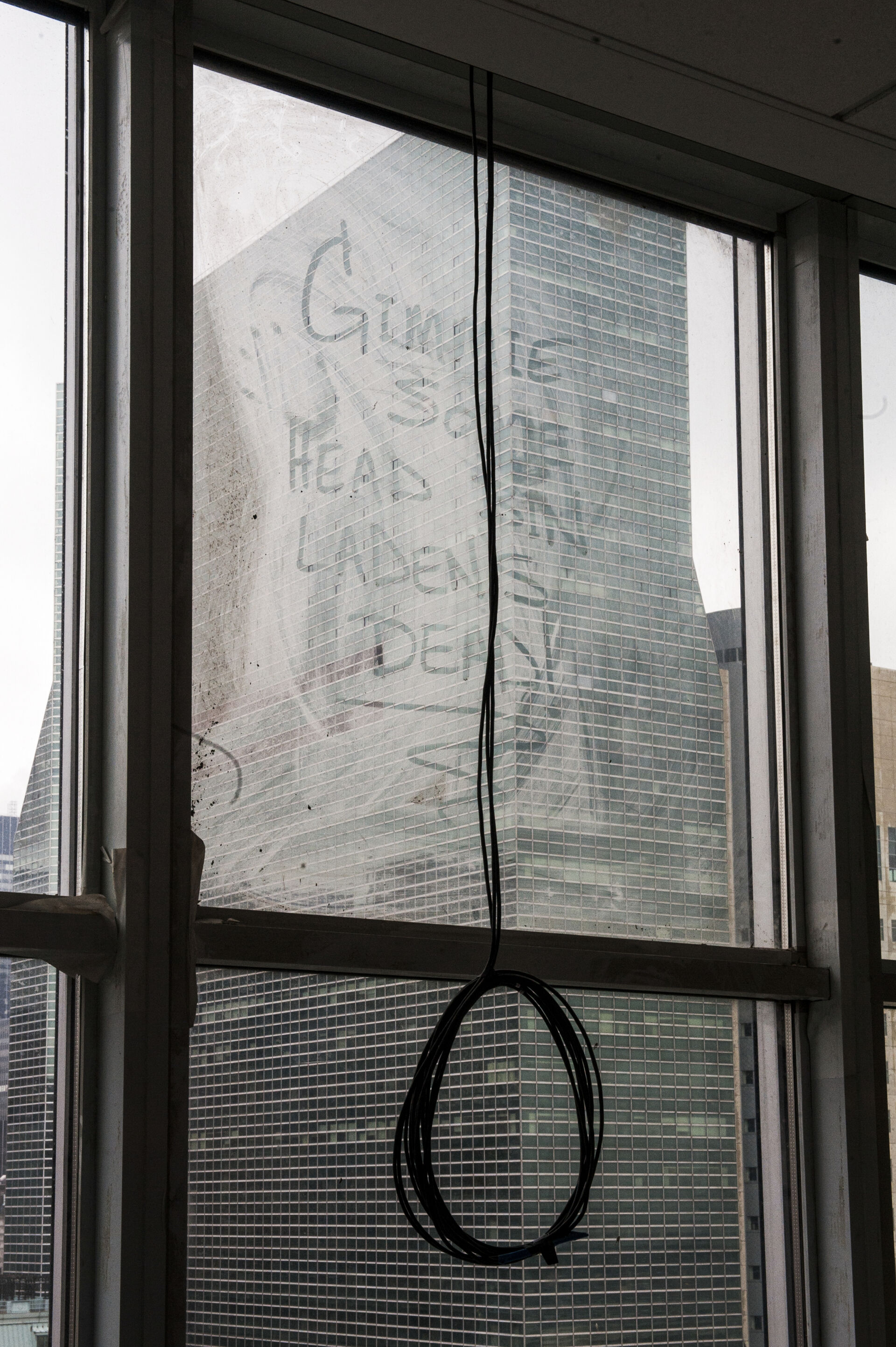

A something-to-be-done, in the context of the visual world, is an action, an approach in which artists, journalists, photographers or writers proclaim that something is worth looking into, that it is worth recording and understanding. Peter van Agtmael’s practice evokes this attitude. For the past two decades, van Agtmael has been documenting conflict and its aftermath both in the Middle East and in the United States, as well as the refugee crisis in parts of Europe and Iraq during the time of ISIS. His book Sorry for the War is a record and a revelation of the dissonance that exists between the way the post-9/11 wars are perceived in America and the very real and shattering impact they have on those who are unable to leave these war zones. The photographs in Sorry for the War were taken over the past 15 years and form part of a non-linear, visual narrative that feels more intuitive than it does orderly, weaving together geographic spaces, time zones, mediums and narratives of propaganda and myth-making. In the acknowledgments that appear at the end, van Agtmael dedicates the photobook to the anonymous lives caught in the middle of America’s wars. The text, comprised of a short essay and long captions, is printed in both English and Arabic (the latter in a translation by Nancy Naser Al Deen), opening up the conversation to an Arabic audience as well as a western one.

The book's title is both a genuine attempt at an apology and an ironic nod to the fraught idea of collective empathy. It was inspired by a photograph of a Post-it note which van Agtmael saw in 2013 at an exhibition in New York’s Ludlow Studios titled Balloons for Kabul. The exhibition invited passers-by to write notes addressing the people of Kabul that would be given to them alongside pink balloons. Though the sentiment behind the sentence ‘sorry for the war’ is benign, something about its naivete echoes a level of desensitization caused by some twenty-plus years of conflict and mirrors a certain form of helplessness and despair. To apologize for a war changes nothing about the reality of its happenings. In most cases, it only further amplifies the dissonance between the perceptions of war in the US and abroad. While the book’s title uses this formal apology, the contents of the book highlight the concrete ways in which this dissonance appears. In the only essay featured in the book, van Agtmael shares: ‘There’s a feeling of fulfilment but also of emptiness when the complexity of my experiences inadequately collapses into the two dimensions of a photograph.’2. Peter van Agtmael, Sorry for the War (Mass Books, 2020).

The book is van Agtmael’s fourth, following 2nd Tour Hope I Don’t Die (2009), Disco Night Sept 11 (2014), and Buzzing at the Sill (2017). Though the books are not a continuous series, together they encompass van Agtmael’s rich body of work – spanning nearly two decades of reporting in warzones. Each reflects in its own way on the US’ collective struggle to reckon with the consequences of violence, anger and fear that came about after the World Trade Center attacks. Though the nature of the photographs forebodes violence and grief, there is a gentle approach towards groups that have been visually marginalized and typically only represented in moments of deep misfortune.

Looking at these images and taking in the photographer’s diaristic observations in the captions that appear at the end of the book, Sorry for the War prompts the following questions: What can we make of this narrative? How do we reckon with the changing character of war in a geopolitical context? And what is the role of photography in this process?

When confronted with images of war, one is often at a loss as to what to make of them. As a writer and critic raised in the Middle East, in the vicinity of the very places of conflict that are represented in most war photographs, and now living in diaspora in the US, I am both overwhelmed with grief and ashamed by my ability to feel desensitized to these atrocities. This, of course, is simultaneously a privilege and a coping mechanism. Peter van Agtmael’s photographs do not make the viewer want to recoil in fear, but instead invite us to look closer: to examine the writing on a child’s overalls hung on barbed wire; to decipher a woman walking in a field, almost camouflaged, looking back and locking eyes with the camera’s viewfinder; and even to read a hotel breakfast sign that we would otherwise have overlooked (‘In remembrance of those we lost on 9/11 the hotel will provide complimentary coffee and mini muffins from 8:45 – 9:15am’). Here, the emphasis is on the subtle forms of violence that keep a conflict alive, both in reality and in representation.

In the caption of his photograph of the Checkpoint Charlie Museum in Berlin, van Agtmael remarks: ‘The detailed but convoluted narrative of the museum made me wonder how we define our collective history. Who are the gatekeepers of knowledge, and how do we find something that can pass as objective truth?’Van Agtmael, Sorry for the War.A similar question was asked some twenty years ago – around the same time that van Agtmael first embarked on his journey as a documentary photographer – by Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). In this seminal book-length essay, Sontag declares: ‘images cannot be more than an invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn, to examine the rationalizations for mass suffering offered by established powers. Who caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable?’4. Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 91.

An invitation to pay attention prompts the need to find something that can pass as objective truth, via photographs that are meant to convey a (very subjective) narrative. Peter van Agtmael is very aware of his positionality, of the horizon of choice that allows him to leave the battlefield whenever he wants to. In this body of work, van Agtmael is conveying a particular truth, the one that tells us that in such situations, positions of power are real, and the fact that these photographs circulate to varied audiences turns them into truth. After all, for those who are not there, something becomes real by being photographed.

Another truth is that being a spectator of calamities taking place in other countries is a quintessentially modern experience – one in which we have all partaken, one way or another. In Hito Steyerl’s 2004 experimental video titled November, a self-reflexive examination of the role of images in the post-revolutionary moment, the artist proclaims over a scene where she marches in a demonstration in Germany: ‘In every war, the principle applies that the truth is the first thing to be sacrificed.’Hito Steyerl, “November”, 25:14, 2004, https://vimeo.com/88484604.

While we can’t pinpoint with certainty the truths being sacrificed in these ongoing conflicts, the photographs in Sorry for the War provide a way to frame this issue. By juxtaposing images from the US with images and scenes of conflict abroad, van Agtmael reveals a disconnect between the lived consequences of the war in different geographies. This effect is heightened by a juxtaposition of different media: intermixed with van Agtmael’s photographs we find still frames of televised political events, a still from an ISIS recruitment video, music videos and scenes from patriotic American movies. This variety of sources and the fact that they exist together with photographs taken in places of conflict create an intriguing narrative – one that is representative of the way these dissonances are experienced on an individual and collective level. In this mix of screenshots and stills, people and spaces are caught in transitional moments; the frailty is palpable, even a little unsettling. In this way, van Agtmael becomes not just an image-maker, but a mediator of images as well.

These liminal moments caught in the photographs in Sorry for the War bring us back to the term we started with: haunting. Gordon uses the term to describe ‘those singular and yet repetitive instances when home becomes unfamiliar, when your bearings on the world lose direction, when the over-and-done-with comes alive, when what’s been in your blind field comes into view.’Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 34 In many ways, this is exactly what photography does: it makes what was once invisible come into view. But it is also a testament to how we reckon with the modern world and its atrocities. A photographer picks up a camera and in doing so decides that what they see is worth recording, that this moment is important, that what is happening here needs to be known. Peter van Agtmael’s photographs bring a parallel into view, and in doing so, direct our attention to the connections and disconnections we may have otherwise missed.