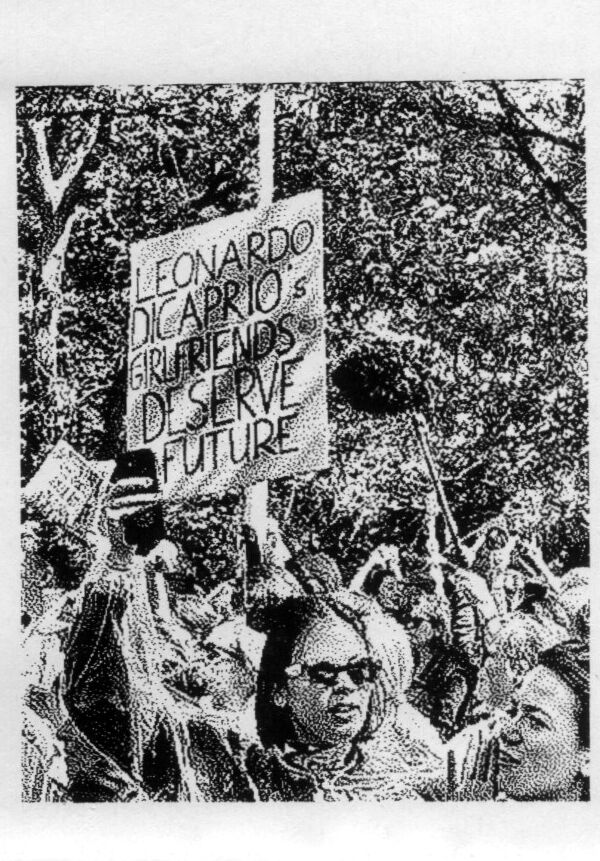

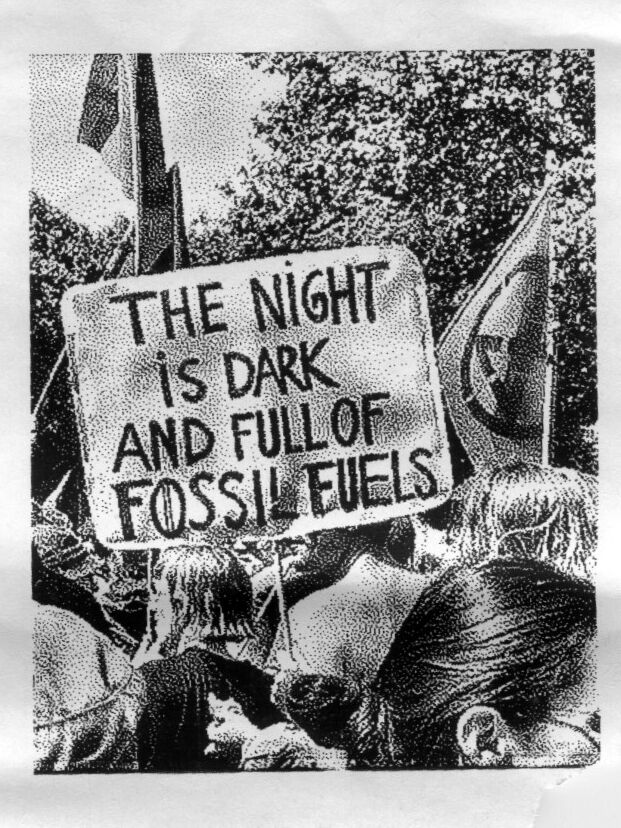

If you’ve ever attended or participated in a protest, you might have experienced how a diversity of perspectives gives rise to different means of documenting that same protest. There’s the professional photographer, the police surveillance, the supporters of protesters, and, of course, the activists. There are banners, flags, people chanting, some police opposition, and, at times, instances of destruction of property or violence.

This is my attempt at indexing layers and understanding the dynamics of image-making during a protest for climate justice. I examine to the ways in which these images travel through social and regular media, police systems, or activist networks of solidarity and become either instruments of illustrating a protest or of legal evidence. Through this, I hold space for the power that imagery has – to push a cause, to bring about some form of justice, to hold to account, to unite a cause.

My reflections started with an image I’ll only reveal towards the end. It was provided to me after I thought my reflections on the topic had ended. The image is a screenshot of a video. It’s an image that I’m a subject of, or one frame before I become its subject. The image made its way to my Instagram DMs on 2 June 2023, at 11:05 p.m.

Selfie with overlayed social media template frame announcing the protest.

iPhone Camera roll overview documenting the protest

First, what came before it? To give a bit of context, I had taken part in a highway blockade organized by Extinction Rebellion.Extinction Rebellion is a UK-founded global and politically non-partisan movement that uses nonviolent direct action to persuade governments to act justly on the climate and ecological emergency.https://rebellion.global/.&nbs... on the A12 highway in The Hague, The Netherlands, on the 27th of May. I had posted about it extensively on social media, as a way to openly journal and clear my head about the experience, as well as in anticipation of it, to promote the blockade and attract more participants.

I mentioned the steps the protest took and how there’s a very funny feeling being in the middle of a protest like the Extinction Rebellion blockade. There are weeks of preparation before stepping on the highway, and then many days after reserved to process what happened and check in with one’s group and buddy. And then, if the weather holds, it can feel incredibly joyous. Which it did! Like a collective party where everyone works towards one goal: in this case, cutting fossil fuel subsidies through direct citizen action by blocking a highway. Around 6,000 people joined either on the highway or in the support demo on the sides on that day.

German water cannons were brought in and deployed fifteen minutes into the blockade, entrapping protesters from both sides and needing to be refilled several times throughout the day. They were counteracted by people in swimsuits with inflatables and kids refilling their water pistols from the puddles that formed. Water went full circle and in both directions.

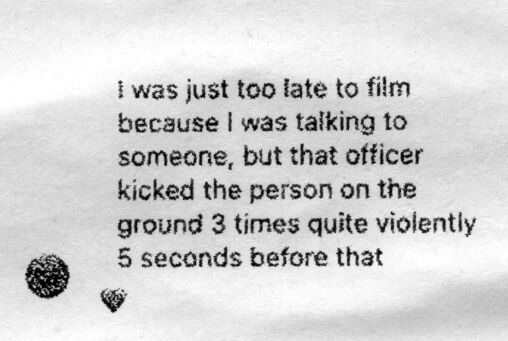

1,579 people were taken from the highway, but not arrested. The majority were put in buses, some with an excess of force – I count myself among them, having been kicked in the shin and hit over the head without any justification – and displaced to the Bingoal Stadium in The Hague, then released. There’s a pretty good system in place to know who was taken and where, but no registration on the part of the police was done for the majority of the protestors.

The action took around six hours on the highway. It was possible to come back and see what was left of it. All protesters were taken no more than thirty minutes away from the location. It felt incomplete. A feeling of emptiness followed, the odd disconnect between body and mind, effort and effect. On a more personal note – though one that was shared by many protesters – there was also the surreal feeling of seeing oneself being treated violently by the police in a video taken by another person. And of course, the lived experience of that.

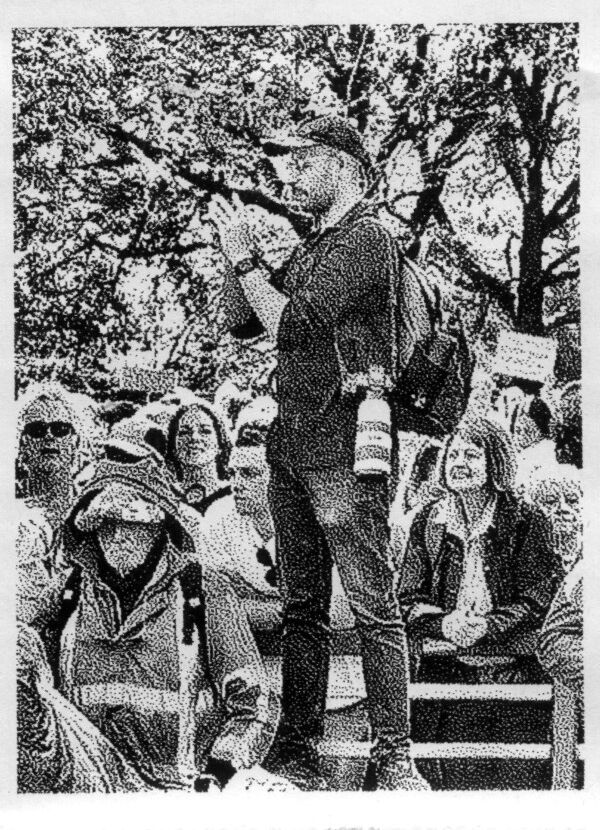

One of my professional photographer friends joined the protest. He showed up with his pro gear: R5 Canon, two lenses 24:70, 70:200 – in his words, a very basic classic photojournalistic assignment setup. He stood in the support demo, glided through the crowd, but amusingly ended up missing my arrest while he was looking for the next shot to catch, right under my eyes.

I have a picture of him in the crowd. He has a picture of me in the protest.

Both photos were taken with our phones and shared between us via WhatsApp messages in real time. They live in my camera roll among videos and pictures of the protest caught in between participation.

I have a vague recollection of Greta Thunberg, the poster child of the climate movement, reposting them on her feed.

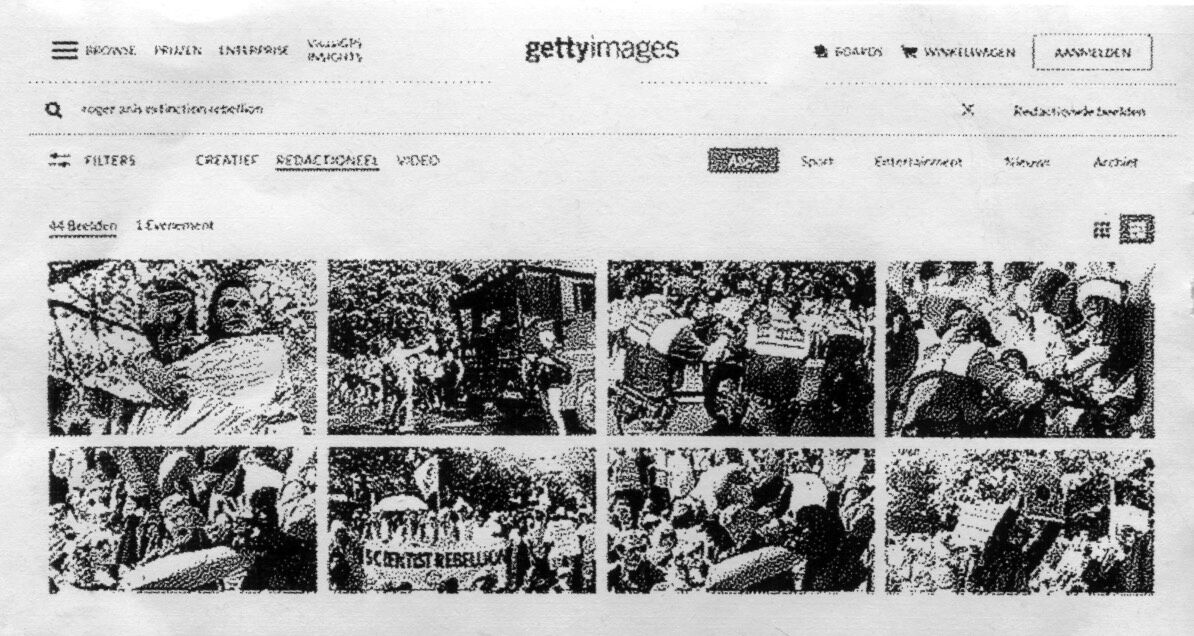

Curious and not at all taking things for granted, I asked my friend and I was told there are two ways with Getty: either you are assigned as a photographer or you can contribute photographs you already have. In the latter case, the photographer gets a percentage each time their picture is used or sold for a client. In this protest, he was a contributor. This was a new position that he took. He’d usually operate on an assignment basis, by being told where to go and what to shoot. This time, knowing the protest was happening on short notice and being able to reach it fast meant that he didn’t need to wait for an assignment. He could just grab his gear and dive in. The percentage of the price he gets is around thirty to thirty-five percent, on a sliding scale depending on the size of the image used (small is €150.00, medium is €335.00, and big is €475.00, where big is defined as 4514 × 3009 px, 38.22 × 25.48 cm, 300 dpi, 13.6 MP). Prices are visible on the Getty website. And there is a contract with the agency.

A professional photographer has the advantage of direct negotiation with the police by waving their press pass or reaching out to police liaisons before they start taking pictures. This was the first time my friend had been to an Extinction Rebellion protest, and he’d never heard of the collective beforehand. One can notice a hint of imprecision in the captions to his Twitter post: the mention of hundreds of protesters present (thousands would have been more accurate) and 1,500 arrested.

I asked him how he chose what to photograph, and he noted the steps he took: ‘I observe – I don’t take pictures immediately. I read the signs; I see the atmosphere; I see how the police are acting. I take a spot to see a general view, but also to go closer. Once I have an idea, I start to shoot.’

In this case, he broke down the dynamics for me: ‘I just see the atmosphere, people chanting, water cannons; then slowly you see the police approaching. Sometimes I ask people around for a translation, since many things were in Dutch. Also, I go next to the police in the beginning to let them know that I exist and show them my press pass – to not get attacked and also to know their attitude in relation to press.’

After talking to him, I was left to gather my thoughts. I waxed poetically about the contrast in being a part of a collective organising a protest and figuring things out on the spot. There’s the difference between understanding scale; needing processing time after an action;https://www.instagram.com/p/CsyA7RYoVgv/, https://www.instagram.com/p/CsyBgNgoPU9/, https://www.instagram.com/p/CsyCHoMImjN/, https://www.instagram.com/p/CsyDDjcIIQ6/. doing the care work needed to support a process before, during, and after; and diving in, figuring things out on the spot, doing the work, and moving on to the next assignment straight away.

There was real-time regret from my side that he had missed the violence against me. Fortunately, in the crowd, my arrest and its associated violence didn’t go completely unnoticed: it ended up being partially documented by another Extinction Rebellion member in the blockade.

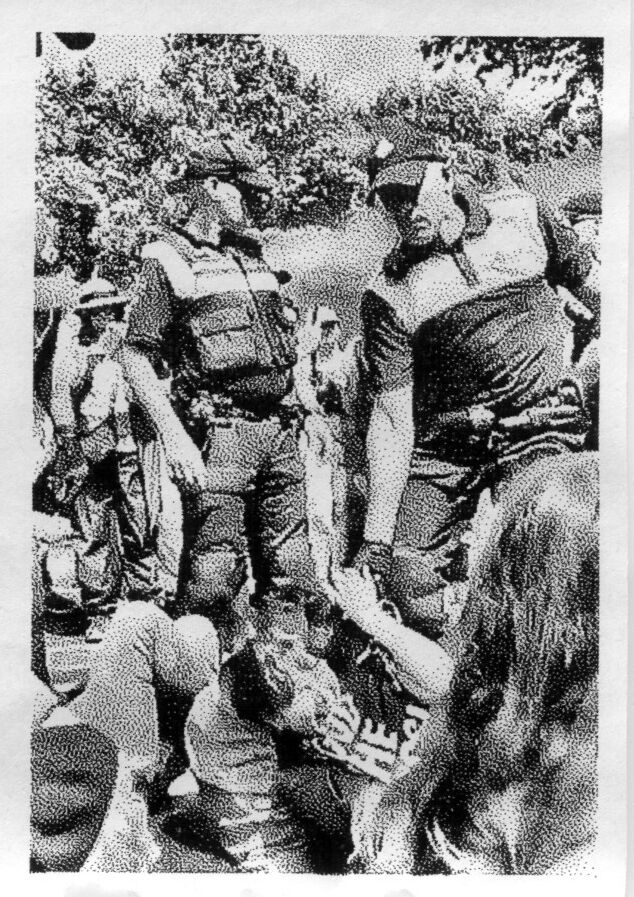

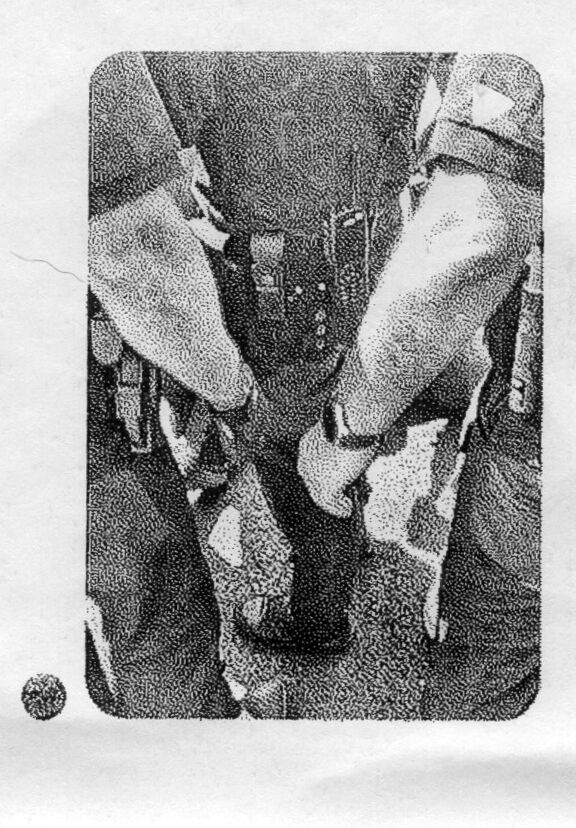

Screencap of police violence.

I was confronted personally with the urgency of needing to document what was happening but not being able to before, during, or after being hit by the police. My phone – my only means of documentation – ended up being cradled close to my chest. I’d slid it into my T-shirt, close to my skin, seconds before joining arms with my group, before being arrested. Days later, after posting a notice about needing to make a complaint to the police, the core of this essay, my appropriated image, came to me.

Screencap of police violence.

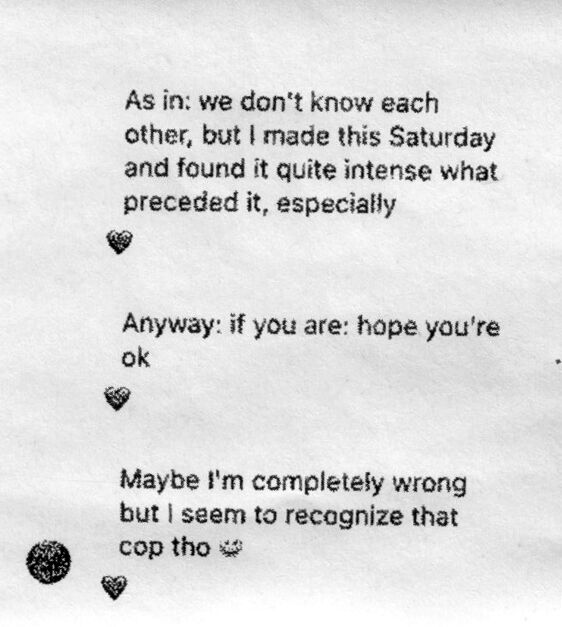

One message was followed quickly by the video, which, due to a poor internet connection at the time, refused to load, stuck in a revolving arrow, before it was finally unstuck so that I could download and play it on repeat. The person who sent me the video didn’t say much by way of introduction – just, ‘Hey, maybe I’m completely wrong, but I just saw this post from you and suddenly wondered: is this you?’

The image: three police officers with their backs turned to the phone camera, the shot taken from top down, and you can see their uncovered arms, watches, gloves, uniforms, walkie-talkies, guns, and leather shoes. The sun is shining on one of the arms. The video play button was frozen on a short shirt sleeve. There is a hint of pavement on which the sun shines, pavement that I remember was covered in an oily substance to deter anyone from gluing their hands to it. There is a certain tension in the police officers’ stances. They seem to be banding together. There are bits of knees and shoes visible on the asphalt – protesters waiting to be picked up, me among them.

To the right side of the image that I’m dissecting, there’s the continuation of my dialogue with the sender:

This was the message I sent over as soon as I pressed play on the video and watched it a few times in awe.

The video had already made it further than my inbox before it reached me, since there’s a structure in place during such protests allowing anyone with evidence to submit it to the Extinction Rebellion legal team. The video would further make its way to the police as a way of keeping those who have a monopoly in violence in check. But the accountability process would be much slower. It reminded me that filing a complaint is not an act meant to resolve a problem, heal a wound, or find a way to bring clarity. Filing a complaint seems to be just a way to understand the trajectory that a complaint has, to illustrate it for others. There are obstructions, and ways to protect the institution and its representatives, but rarely is there a way to resolve the complaint for the one making it. The videos and images would need to be uploaded on a special police platform via a link sent by the representatives of the police via email.

To file a complaint against the police for police violence seems redundant. The police should first and foremost know when an act of violence takes place, and they should make sure to stand against it, document it, and correct it. Of course, this is never truly the case. Having the visuals for it would offer only some support in being able to file a complaint. They would, however, help begin a process of understanding how complaints work. In The Hague, there is a police representative in charge of all Extinction Rebellion protests. Their job is to ‘re-establish trust’ and ‘learn from complaints’, and despite incidents having happened during the protest, few people have followed through in submitting a report. Some might have needed to not cloud the overall positive experience with anything negative; others might find it a high threshold to email or call. Others still might find it slow, this process, and cumbersome to be told to go to a local police station to file a report. There could also be a slight language barrier. Others still might have no visual support for their claims.

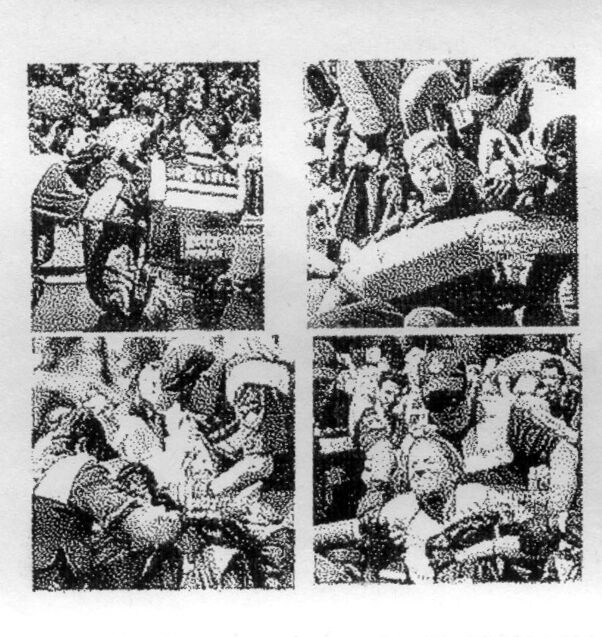

Back to my professional photographer friend. His professional shots also revealed excessive police handling, though not framed as such.

Accidental professional documentation of police violence.

His images, devoid of context except for the time, the place, and the organisation participating in the protest, could nevertheless also be used as evidence of mishandling, but only if they made their way into the hands of the people in the shots or of those in charge of keeping track of boundary crossing. A protest in a public space is in the arena par excellence of the press photographer. But it is also, due to the ubiquity of mobile phones and the online presence of those holding them, a place where every member of the collective who engages in protest can serve as a witness for their community.

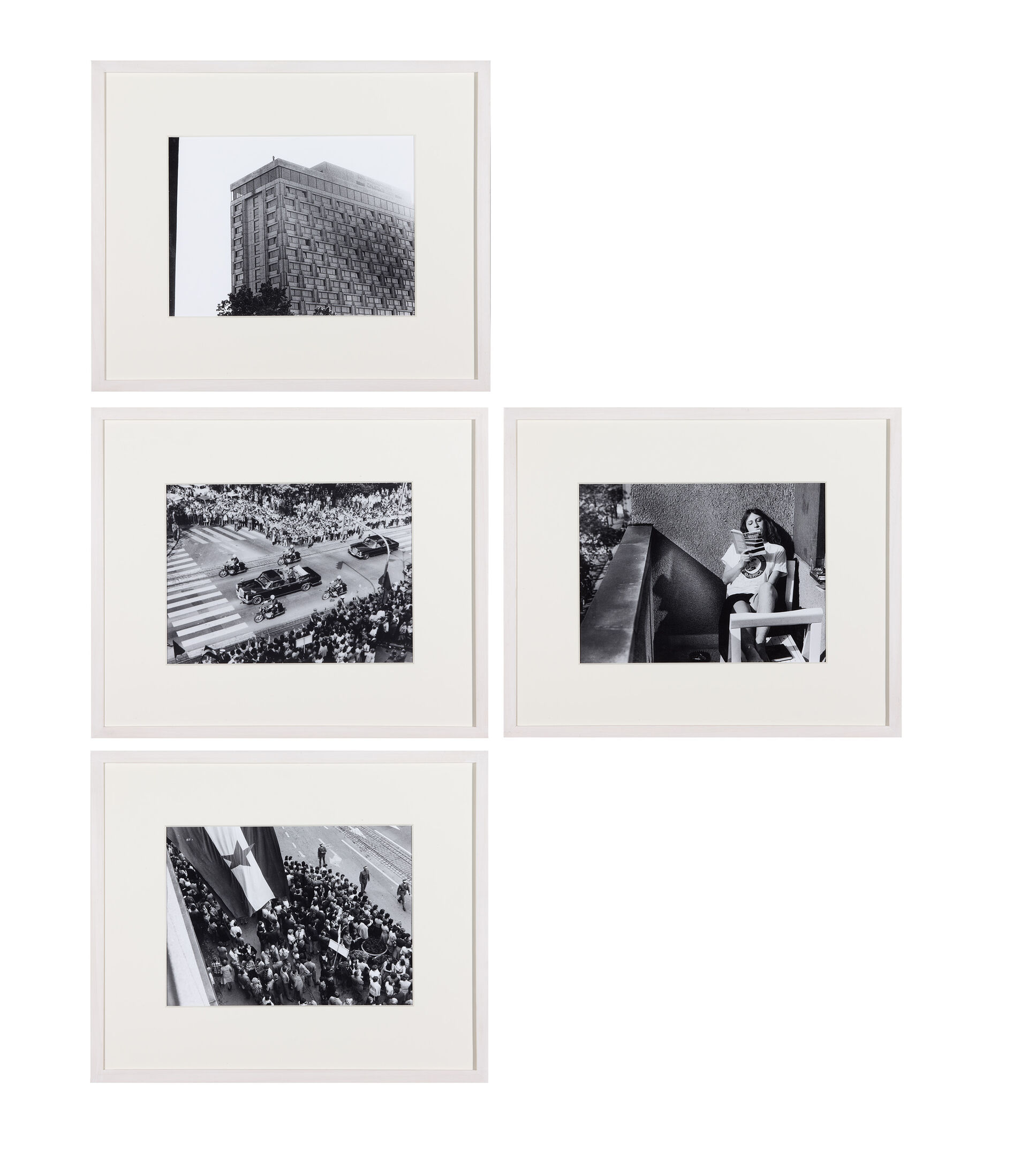

I ultimately got reminded of an artwork that speaks of multiple angles and multiple ways of documenting, in dialogue with structures of power. The work is Trokut (Triangle) by Sanja Ivekovic, from 1979.‘This group of four photographs and one text documents Sanja Ivekovic’s performance in Zagreb on the 10th of May 1979, the day of President Tito’s visit to the city. The artist describes the interaction that took place between her (on the balcony of her apartment), a person who could see her from a rooftop and a policeman supposedly communicating by walkie-talkie with the observer. According to the text accompanying the photographs: “The action begins when I walk out onto the balcony and sit on a chair, I sip whiskey, read a book, and make gestures as if I perform masturbation. After a period of time, the policeman rings my doorbell and orders the ‘persons and objects are to be removed from the balcony’.” Trokut (Triangle) is representative of Sanja Ivekovic’s work in the 1970s, in that it sets up a confrontation between public and private spaces, exemplifying both her political activism from a critical perspective and her interest in dealing with gender-related issues.’

Sanja Iveković's Triangle work from AfterAll's 'One Work' series by Ruth Noack © Sanja Ivekovic

In Ivekovic’s work, the purpose was to see how fast one can be seen, and held in check, abiding by the morals of the time. The core of her performance was to simulate the act of masturbating in a semi-public space, under the watchful eyes of the police, during a visit of then-President Tito to her city. In the documented performance, there are three angles presented in four photos: one of Ivekovic on her balcony, one of the security agents from a nearby high-rise, and two of the presidential procession.

There is a contrast between Ivekovic’s action and the dynamics of a protest like the Extinction Rebellion one, where monitoring happened from multiple angles – audience, press, police. In the case of Extinction Rebellion the true challenge would be the idea of holding someone accountable, and the follow-up question would be for what.

What transgression is more egregious? What acts are considered violent in public, once they’re discovered? And who’s allowed to carry them out without repercussions?

Two weeks after the protest, the video evidence I’d gathered of the violence against me had yet to lead to any follow-up. Identification of the officers whose faces were visible on the video had not been possible. Communication between the police in The Hague, where the protest took place, and the police in Amsterdam, where I live, had been cumbersome, since each follow different steps in processing complaints.

My professional photographer classmate had managed to sell a couple of his images via Getty. They have not served as official evidence of police violence.

I wondered what additional angles I missed in my documentation – who else had their camera pointed toward me while I was picked up?

I wondered what the effect of having my camera phone accessible and pointed at the officers arresting me would have been, and whether it could have acted as a shield against violence.

While reviewing this piece, on 8 February 2024, eight months after the fact, I have yet to receive any follow-up from the authorities.

Editor's note. This contribution is part of our 'Unframing' series. Read the introduction by guest-editor Nuria Bofarull here.