©Dragana Jurišić

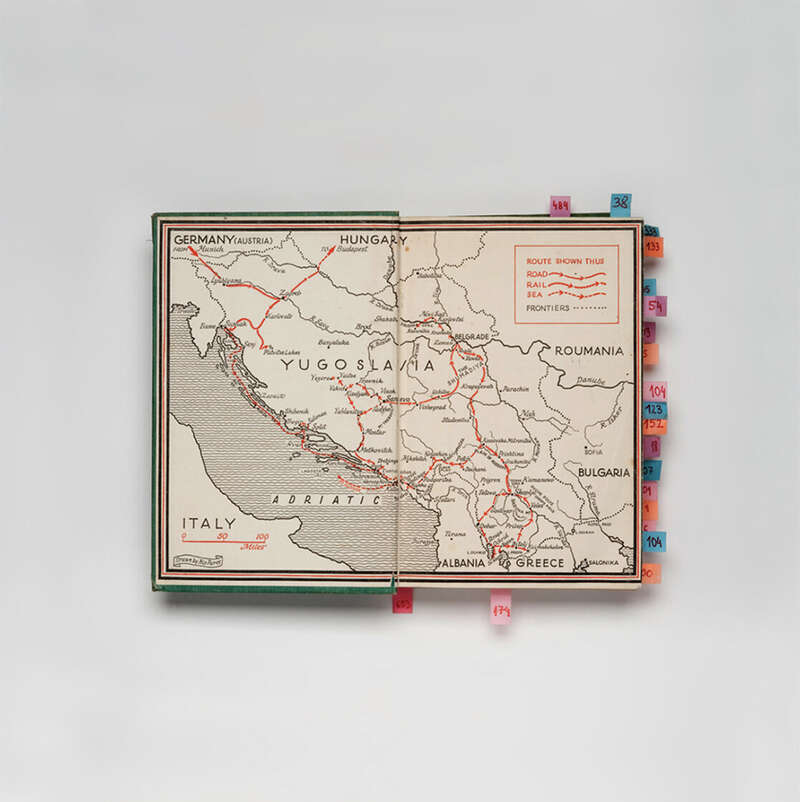

A picture of her copy of Rebecca West's Back Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), with a map of Yugoslavia.

Sisters in Exile, Searching for YU

Writer and photographer Brian Arnold, currently developing a new book of essays about photography in Serbia and Yugoslavia, compares the photographic diaries by two 'former Yugoslavia' photographers, Dragana Jurišić and Olja Triaška Stefanović. He sees their work as good starting point for further investigations into (what was) Yugoslavia. Arnold untangles the complex personal and cultural associations he finds in their photobooks. For this he reverts to the figure and story of Atlantis.

Brian C. Arnold

23 nov. 2024 • 21 min

In those histories, half tradition,/With their mystical thread of gold,/We shall find the name and story/Of thy cities, fair and old;/Wandering minstrel sung of thee,/Now, above thee, lost Atlantis,/Rolls the ever restless sea.Phelon, W. P., Our Story of Atlantis: Written Down for the Hermetic Brotherhood, p. 1-2. San Francisco: Hermetic Book Concern, 1903.

- W. P. Phelon, M. D.

Like any good story, the ancient myth of Atlantis is full of contradictions. Some legends cast it as a utopia, a moral and spiritual haven in the Mediterranean. More commonly, the people of Atlantis were acknowledged as highly advanced and civilised but extremely warlike. The island nation first appears in Plato’s Timaeus and Critias and is used allegorically by the great philosopher to describe the hubris of nations, the ego and avarice that eventually lead to the fall of civilisations. Atlantis was a naval empire that controlled much of the Western seas, but lost favour with the gods after a failed attempt to conquer Athens. As punishment, Zeus drowned the islands and leaves them for history.

The story of Atlantis exists across world mythologies, and centuries of children’s authors have incorporated the legend into tales of moral philosophy and human folly. It’s part of the DC Comics universe in Aquaman, personified by gorgeous Baywatch alum Jason Momoa, the ethical warrior of the oceans. In college, I discovered a book called The Secret Teachings of All Ages by the esoteric religious philosopher Manly P. Hall, who enshrined the legend as an essential part of Western epistemology, featuring it alongside discussions of Kabbalah, Paracelsus and the alchemists, astrology, and Pythagoras’s philosophies of music and colour.

Clearly, the story is worthy of our attention and can tell us something about the puzzles of civilisation; after all, some histories are best understood using allegories and metaphors. Anyone attuned to the news today can witness the hubris of nations and the ongoing collapse of civilisations. Watching states and cultures fall is much more barbaric than the collapse of Atlantis suggests, but the legend also begs us to ask some important questions. If Plato intended the story of Atlantis as an allegory for government hubris, why not just punish the government? Why destroy the citizens too? And where are the survivors of Atlantis? Life is tenacious and I can’t imagine Aquaman is the only one left; what about those who survived? Do they tell a different story about the fall of their nation? The last of these is most intriguing to me, because too often history is about governments and empires, not people; personally, I’d rather hear the stories of the survivors.

* * * * * * *

Perhaps the only defence of our freedom and identity is the ability to reject the insidious question directed at us by others and ask our own question. With the right to not provide an answer if I’m not sure.Šimečka, Martin M., "The Insidious Nature of the Question Who Are You?", from Brotherhood and Unity by Olja Triaška Stefanović, p. 165. Bratislava: Academy of Fine Arts and Design Bratislava, 2020.

- Martin M. Šimečka

Born in Novi Sad in 1978, photographer Olja Triaška Stefanović left for Bratislava in 1997, years after enduring the trauma of the Balkan wars in Novi Sad, the lovely Austrian-style city about an hour north of Belgrade. Today we know Belgrade as the capital of Serbia, but not so long ago it was the capital of a country now lost to history, Yugoslavia. When Stefanović arrived in Bratislava, she didn’t speak a word of Slovak but enrolled in the Academy of Fine Art and Design to pursue photography. Before Stefanović left home, she studied in Sremski Karlovci (a small city outside of Novi Sad) and completed an independent thesis project on the history of photography among the South Slavs.

Eighteen years after she left for Slovakia, Stefanović recognised herself as a fully Central and Eastern European woman. A Professor of Photography at the art academy in Bratislava and fluent in several languages – including Slovak, Czech, German, Polish, English, and Serbo-Croatian – she understood herself as self-actualised woman, independent of her family and homeland, and conversant with cultures across the region.

©Olja Triaška Stefanović

She also felt an ache to reconnect with her childhood in Yugoslavia, understanding this was still at the core of who she is today; over the next several years she began a photographic study of her homeland. Stefanović also felt the need to confront the trauma of war, on both personal and cultural levels, and perhaps to find closure for all the pain caused by the civil wars that divided her family and erased Yugoslavia. The result is Brotherhood and Unity, an interdisciplinary art project and book developed over seven years, addressing complex issues about regional history, collective trauma, personal identity, and the nature of home.

Stefanović started her journey home in Slovenia, then travelled through Bosnia and Croatia and finally to Serbia. As she did so, she networked with artists and academics using her credentials from Bratislava, connections that helped her find ideas and locations to photograph. The book Brotherhood and Unity (Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava, 2020) is loosely divided into three chapters, each depicting the artist’s travel through time and place, searching inside and out for a look at her childhood and home while questioning what it means to identify as Yugoslav today.

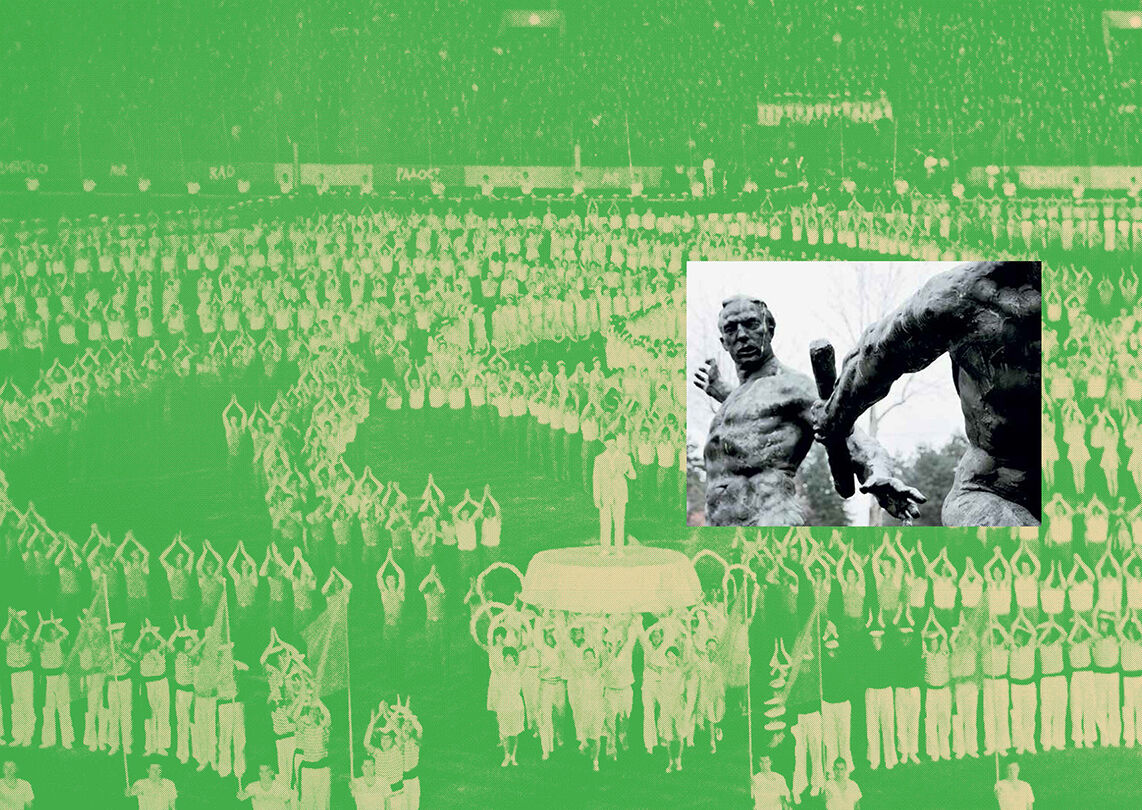

©Olja Triaška Stefanović

The book is composed with photographs gleaned from family albums, newspapers, and historical archives juxtaposed with Stefanović’s own pictures. She photographed traces of her former country – its monuments, brutalist architecture, and hillsides where the grasses and trees grew over historical sites of a forgotten nation. The title is a reference to a World War II call to arms among Yugoslavs, later a notion that provided a guiding principle of governance for President Josip Broz Tito, the Partisan leader who unified the country after the war.

©Olja Triaška Stefanović

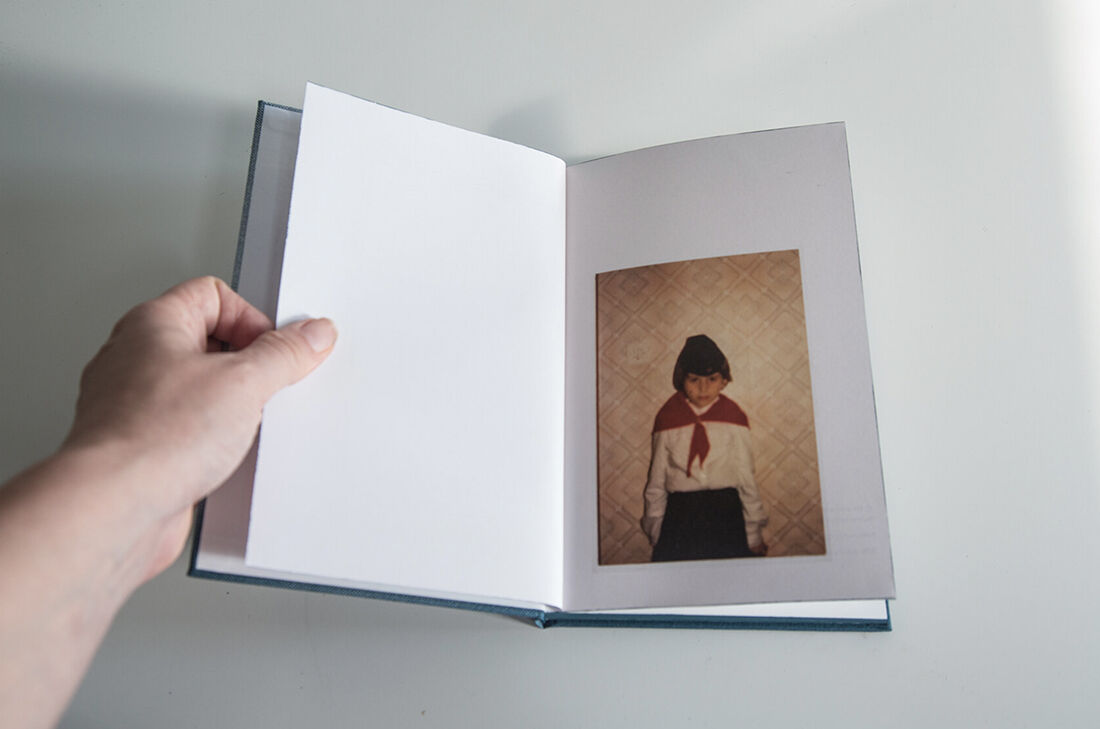

The first chapter of Brotherhood and Unity focuses on Stefanović’s childhood and includes photographs of her as a young girl – family snapshots and school pictures – placed alongside images of Yugoslavia and the nationalist education experienced during her childhood. These are punctuated by pictures of Josip Broz Tito in life and death, the omnipresent and benevolent patriarch that defined the nation for decades. In an interview with Peter Korchnak as part of his project Remembering Yugoslavia, Stefanović describes her intentions for the opening section as a memory montage, bits and pieces cast together to reflect her earliest recollections of life in Yugoslavia.

The narrative switches gears in the second chapter, and rather than being built around Tito, Stefanović next looks at her life under Slobodan Milošević, the infamous leader that weaponised Serbian nationalism. The majority of this section is photographs of residential architecture in Yugoslav cities (I think I recognise at least one from Novi Sad), but these are again interlaced with montages of newspaper clippings about Milošević and the war. The final picture of this chapter is quite curious and serves as a defining picture for the entire narrative. It’s not an especially exciting or unique photograph, like a snapshot from a party but with a more sophisticated intent, showing Stefanović in the middle of three other people, each with their arms crossed and holding hands.

©Olja Triaška Stefanović

They stand in front of several rows of grape vines, each of them looking up and to the right. Stefanović is pictured with her immediate family, standing before a vineyard originally owned by her grandparents. Their pose is a deliberate reference to a Yugoslav folk dance, something like a kolo, and one often seen among the Partisan resistance to fascism during World War II, the dance itself a symbol of the national motto, brotherhood and unity. The artist and her family are bound together, a gesture of unity, but also feel guarded, each of them broken by Milošević’s war and moving towards an unknowable future. In looking at documentation of the exhibition Brotherhood and Unity, the photograph has a prominent and haunting presence, printed large and ghostly on a diaphanous curtain, glowing from the back.

©Olja Triaška Stefanović

The third section, peppered with captions that read ‘THE PRESENCE OF THE PAST’ and ‘REMEMBERANCE AND FORGETTING’, is developed more with what I like to call a Yugoslav terrain vague. Originally used as an architectural term to describe the spatial detritus of cities, the leftover spaces around the edges, the idea of terrain vague was quickly co-opted by photographers after New Topographics, an exhibition held at the George Eastman Museum in 1975-76 that redefined photographic approaches to the landscapes. Stefanović photographed the detritus and leftover spaces of Yugoslavia, neglected monuments and ruins unclaimed by any nation today, grown over with trees, wildflowers, and decay. She is still able to see the beauty in these places, however, and shows us more than just the decomposition by photographing the uncanny beauty of distinctly socialist, concrete monuments. This contrast is essential for her narrative, and like the family photograph, points to something more substantial than just the ruins.

Brotherhood and Unity ends with a selection of four essays, each providing a deeper context for understanding the pictures. In embracing a broader perspective of the region, journalist and writer Martin M. Šimečka compares the fall of Yugoslavia with the split of Czechoslovakia, a peaceful transition perhaps more comparable to Brexit, but like it’s Eastern European neighbor, more a by-product of the collapse of the Communist Bloc. Šimečka, the son of a prominent Czech dissident, questions what it means to be Slovak or Czech, helping us to better understand what Stefanović means in identifying as a Central and Eastern European citizen, questioning what national identity means after such major reconfigurations of the region.

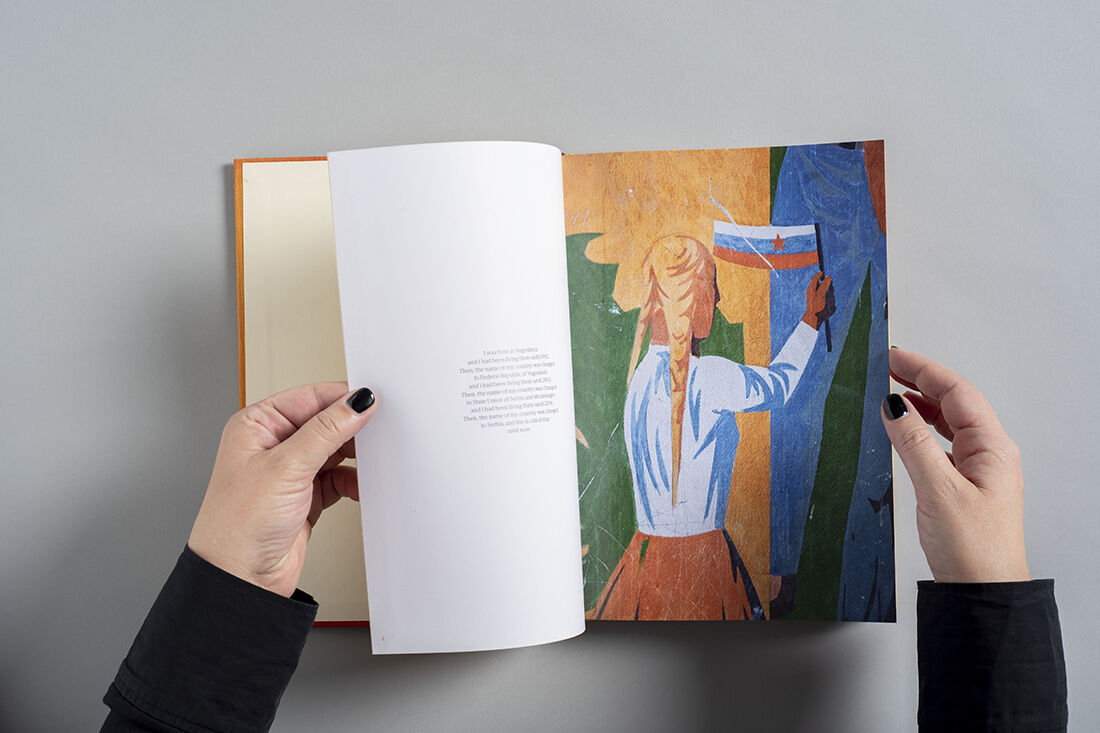

The opening text of Brotherhood and Unity perfectly encapsulates the entire narrative:

'I was born in Yugoslavia/ and I had been living there until 1992./ Then, the name of my country was changed/ to Federal Republic of Yugoslavia/ and I had been living there until 2003./ Then, the name of my country was changed/ to State Union of Serbia and Montenegro/ and I had been living there until 2006./ Then, the name of my country was changed/ to Serbia, and this called that/ until now.'Stefanović, p. 2.

At the age of fourteen, a crucial time in developing a sense of self, Stefanović was confronted with incredible chaos and confusion, driven by the hubris of her government and its need to promote nationalism, ultimately ending in the fall of Yugoslavia. Perhaps what this text describes is a national identity crisis, but one inherited by Stafanović when she fled for Bratislava and reinvented herself as an artist, an experience that’s captured in Brotherhood and Unity.

* * * * * * *

©Dragana Jurišić

To be afraid of sorrow is to be afraid of joy.West, Rebecca, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia, p. 420. New York: Penguiin Books, 1994.

- Rebecca West

YU: The Lost Country (Oonagh Young Gallery, 2015) by Dragana Jurišić tells a similar story shaped by her experience growing up during the war. Jurišić, however, grew up on the other side of the conflict in Croatia. Born in 1975 in Slavonski Brod, a small city on the border of Bosnia and just about an hour from Vukovar, Jurišić is the child of a mixed family – her mother Serbian Orthodox, her father Croatian. Like Stefanović, Jurišić left home in 1999, four years after the signing of the Dayton Accords, the peace agreement that ended the conflicts between Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia. After a short stay in Prague, Jurišić eventually settled in Ireland and enrolled in a photography program in the University of South Wales, completing a PhD in fine arts in 2013. Jurišić’s dissertation, ‘The Lost Country: Seeing Yugoslavia Through the Eyes of the Displaced’, evolved into YU: The Lost Country, a highly regarded and coveted photobook about her life as a Yugoslav exile.

To truly engage The Lost Country, one must first know a little about Rebecca West’s masterpiece of travel literature, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A renowned writer British writer and intellectual, West travelled Yugoslavia between 1936 and 1938 and published the book in 1941. Black Lamb and Grey Falcon provides a literal record of her journeys through Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Old Serbia (Kosovo today), Montenegro, and Macedonia. The book is remarkable in so many ways, chief among them the compelling prose that knits together a complex understanding of the region’s history with West’s own adventures, seamlessly flowing between descriptions of harrowing roads and exquisite meals (staple travel literature) with an extremely nuanced and exhaustively researched history of the various states in Yugoslavia. With incredible insight and affection, West understood the essential role of the Balkans, the region she felt truly shaped the history of greater Europe in the twentieth century. In the same interview with Korchnak for Remembering Yugoslavia, Jurišić characterises Black Lamb and Grey Falcon as a ‘repository of memories for a country that no longer exists’.

The Lost Country is deliberately built using West’s famous work, literally trying to retrace the author’s footsteps (even staying in the same hotels, whenever possible) as she first tried to (re)discover Yugoslavia. Jurišić’s book is simpler in its construction than Brotherhood and Unity, framed with short introductory and concluding statements (both written by Jurišić); most of the book is composed of her photographs. The pictures are presented in the same narrative chronology as Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, starting in Croatia and then travelling to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro. Jurišić presents the pictures just one per page spread, each captioned with its locale and accompanied by short descriptions – some of these written by Jurišić and others are quotes from West. Like Brotherhood and Unity, Jurišić uses family snapshots to personalise her story; both open their books with pictures of the artists as young girls. In The Lost Country, we see Jurišić begrudgingly posed against a geometric wallpaper wearing her school uniform: plain-coloured shirt and skirt, a dark cap with a small red star on the front – a symbol of Yugoslavia under communism – and a red scarf tied around her shoulders, situating her as distinctly a child of Yugoslavia.

©Dragana Jurišić

The strength of Jurišić’s pictures is in the complex personal and cultural associations she brings to each of them. This is perhaps best exemplified by a photograph found in the middle of the book, made in Sarajevo. Like Stafanović’s family photograph, this picture is interesting and deceptively simple; it’s also given prominence in the narrative, printed larger than Jurišić’s other pictures and the only one printed across the page gutter. It shows two people sitting on a concrete bench: on the left, a young man, casual and cool in sunglasses, sits with a relaxed posture; on the right, an older woman, wearing a headscarf, smokes a cigarette with her back turned to him. There is a clear generational gap between them, the young man embodying a modern, urban style and the older woman’s headscarf and demeanour evoking a more traditional Yugoslavia, particularly within Sarajevo’s Muslim community. Yet her appearance defies simple labels; her wide-fitting blazer and the casual act of smoking add unexpected nuances, denying easy interpretations. The image, like much of Jurišić’s work, requires more than a single interpretation, instead inviting viewers to consider the multiple layers of identity and cultural complexity within it. This is further emphasised by the accompanying text, which reveals an entirely new level of complexity: ‘The corner where Franz Ferdinand met his end.’

One of my favourite parts of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, and an essential part of the text, is West’s description of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir of the Austrian Empire, and his wife Sophie, the event that both triggered World War I and helped create an independent Yugoslavia:

'As the automobile remained stock-still Princip was able to take steady aim and shoot Franz Ferdinand in the heart. . . . When he saw the stout, stiff body of the Archduke fall forward he shifted his revolver to take aim at Potiorek. He would have killed him at once had not Sophie thrown herself across the car in one last expression of her great love, and drawn Franz Ferdinand to herself with a movement that brought her across the path of the second bullet. She was already dead with Franz Ferdinand murmured to her, ‘Sophie, Sophie, live for our children’; and he died a quarter of an hour later. So was your life and my life mortally wounded, but so was not the life of the Bosnians, who were indeed restored to life by this act of death.'West, p. 349-350.

Gavrilo Princip was a Bosnian Serb, and his actions revolutionary, an attempt to free Bosnia and Yugoslavia from the colonial presence of the Austrian Empire. With this information, the subject of Jurišić’s picture becomes substantial bigger; it’s still about the generational gap between the two subjects, but it’s also about the violent collisions between East and West, the Ottomans and the Austrians, and events that reshaped Europe.

©Dragana Jurišić

This is how Jurišić composes all her pictures in the book, positioning them against short statements and providing important subtexts for the photographs. Sometimes these reflect personal experiences – like a trip to the zoo in which she recalls her mother taunting a bear, or the challenges she faced crossing into Kosovo with a distinctly Serbian name, Dragana; other times she evokes historical events that define Yugoslavia. Using this strategy, Jurišić creates beautifully visualised photographs that hold an incredible latent content, palpable but elusive in the pictures and clarified by the accompanying text.

Jurišić witnessed the demise of Yugoslavia from the frontlines, an important distinction between her and Stafanović. Novi Sad witnessed military action, but nothing like their neighbours in Croatia. In a closing statement in The Lost Country, Jurišić notes that a garrison for the Yugoslav National Army was visible from her family’s apartment, a site attacked early in the war in 1991. Indeed, Jurišić says her story began when family’s apartment burned down, and she spent several years as an internal refugee in Croatia, scuttling back and forth between different basements and hotels while the war raged on. It was the reconstruction of Croatia, however, that ultimately proved too much for her; disappointment in the right-wing nationalism that emerged under the newly independent nation pushed her out.

©Dragana Jurišić

After relocating in Ireland, Jurišić felt a need to reconnect with her homelands. Alone in Ireland, she felt like an exile, and was determined to return to Yugoslavia and reconnect with herself. Unfortunately, she experienced just the opposite. In her interview with Korchnak, Jurišić describes her experience as attempt to return home and find her people, but says she felt more alienated than she did living in Ireland. Juriśić confronted the reality that the place she grew up, Yugoslavia, no longer existed, and she came to fully recognise and accept herself as an exile, excommunicated from her native lands. The Lost Country provides a moving photographic record of this experience.

* * * * * * *

Every heart has such a country;/Some Atlantis loved and lost –/Whereupon the gleaming sand bars,/One’s life fitful oceans tost;/Mighty cities rose in splendor/Love was monarch of that clime/Now, above the last Atlantis/Rolls the restless sea of time.Phelon, W. P., Our Story of Atlantis: Written Down for the Hermetic Brotherhood, p.2.

- W. P. Phelon, M. D.

I had the good fortune to sit down and talk with both Dragana Jurišić and Olja Triaška Stefanović, a welcome opportunity to learn from them directly. I asked them both a couple of the same questions. What, if any, national identity do you assume today? And what’s it like to talk about war trauma? Jurišić responded as identifying as Yugoslav–Irish, and Stefanović responded by calling herself Vojvodinian–Yugoslav, using this to represent a multicultural sense of self; Vojvodina is an autonomous province in Serbia north of Belgrade, and is a proud, ethnically diverse region – home to Serbs, Croats, Hungarians, Jews, Muslims, Russians, Catholics, and Romanians – that grew under the wing of the Austrian empire, with Stefanović’s hometown Novi Sad at its centre. In addressing trauma, Jurišić evoked the brilliant and upsetting documentary by Joshua Oppenheimer, The Act of Killing, and described her experience of the war today as being like a movie – it’s easy to visualise and share the plot, but it no longer feels like her own experience. When asked the same question, Olja spoke of something remarkably different, equating trauma with the empathy she felt for all the victims of Milošević’s war, such violence and hatred perpetrated under the banner of Serbian nationalism. This feeling of empathy led to some difficult circumstances, including her family’s being monitored by the Serbian government, tagged as wartime dissidents.

Interestingly enough, both artists used their books as starting points for further investigations into Yugoslavia. In November 2024, Stefanović released her second book, Yugoslavia: Intimate Stories of Non-Aligned (Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava). Like Brotherhood and Unity, this book mixes biographical and historical images to narrate another important political philosophy of President Tito. The idea of Non-Alignment dates back to the Bandung Conference organized by Sukarno, the first president of an independent Indonesia, staged in Java in 1955, an attempt to create a unified international political block composed of post-colonial nations refusing to capitulate to the binary structures of the powers competing over the Cold War divisions, eventually ratified in Belgrade in 1961 and used as a primary governing philosophy for Yugoslavia. Jurišić’s second book, Her Own (self-published, 2022) is a fictionalised biography of the artist’s aunt Gordana. Her Own

is a wonderful complex and beautifully designed book reminiscent of W.G. Sebald and narrates the story a woman from rural Yugoslavia who is involved in espionage and accepts a fluid identity as she navigates life between nations. Today, Jurišić is making a film based on the work of Hari Dzekson, a Macedonian film director famous for Westerns, conceived as the last in a trilogy about her homeland.

©Olja Triaška Stefanović

In the opening statement for YU: The Lost Country, Jurišić invokes Atlantis as an archetype for understanding Yugoslavia, a civilisation that was erased from history because of intense internal strife, destroyed by nationalism and the overreach of governments. While putting this together, I revisited The Secret Teachings of All Ages, to again learn what the esoteric philosopher had to say about the lost city; I thought it might teach me something more about Yugoslavia. The nation of Atlantis was in the Aegean Sea, situated between Greece and Turkey, between East and West, and thus a perfect analogy for understanding Yugoslavia, a nation caught between Austria and Western Europe on one side, and the Ottomans and the Communists on the other. Hall approaches the idea of Atlantis like a scientist and looks at a variety of perspectives, including work by modern historians and archaeologists who think the story real. He also goes into detail about Plato’s account, believing the ancient philosopher wanted us to understand the story as both allegory and history. The story of Atlantis starts with Poseidon, the Greek god of the seas, creating the archipelago nation. Poseidon divided the country into ten kingdoms, one for each of his sons, all autonomous but serving under the rule of his eldest, Atlas (this struck me as remarkably similar to Yugoslavia under President Tito, independent states answering to one).

Eventually, Atlantis, great military power that it was, tried to conquer Athens, angering Zeus and resulting in the destruction of the island nation, washed under the sea. The story leads Hall to conclude, ‘If Atlantis be considered as the archetypal sphere, then its immersion signifies the decent of rational, organised consciousness into the illusionary, impermanent realm of irrational, mortal ignorance. Both the sinking of Atlantis and the Biblical story of the “fall from grace” signify spiritual involution.Hall, Manly P., The Secret Teachings of All Ages: An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolic Philosophy, Readers Edition, p. 83. New York: Penguin, 2003. From all I’ve learned about the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, the abandonment of reason and moral negation seem like apt descriptions (I love the phrase spiritual involution), so if this describes the fall of Atlantis it also does the nation of the South Slavs. Making this connection provides me with new ways for understanding Brotherhood and Unity and YU: The Lost Country, both literal, photographic diaries and essential allegories for relating the immense pain of national destruction.