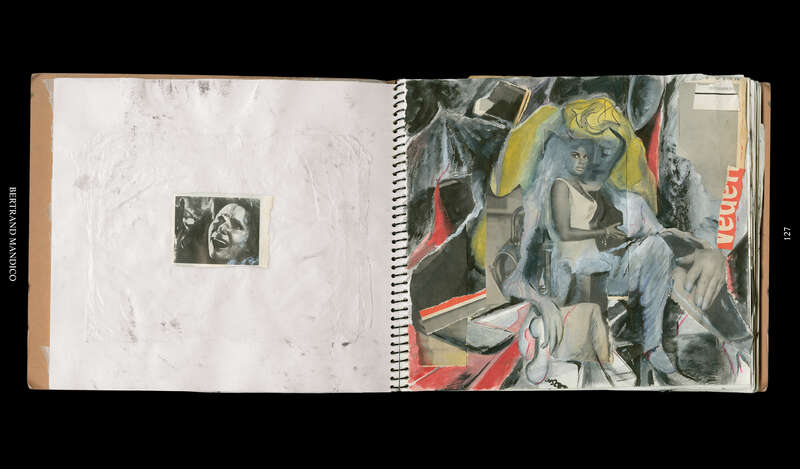

Bertrand Mandico, Scrapbook grand carnet « Croûtes pour films » Scrapbook petit carnet © Bertrand Mandico

Scrapbook Becoming Cinema (1940–1960)

‘Each scrapbook is its own world, compelling and impossibly frustrating,’ writes Ellen Gruber Garvey. ‘Each scrapbook seems both opaque and tantalising on the first reading; magnetic and impossible.’Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 14. What makes scrapbooks so alluring is exactly what makes them hard to define and write about in a general sense. As hybrid objects, scrapbooks share much with written diaries, photo albums, graphic zines, artist sketchbooks and encyclopaedias, and imaginary atlases; they continually move onward, gathering up the outside world into a volume that is decidedly anti-narrative in its refusal to be finished, and likely to refuse definition through its visually metamorphic nature. But what a scrapbook can do is reveal collective culture, and how its maker engaged with it. Each is a unique act of remediation between that individual and the world in expressing a particular creative intimacy with images – photography especially – that can be hard to articulate.

Ellie Howard

27 feb. 2024 • 24 min

Scrapbooks have enjoyed popularity at certain intervals – the 1940s, 1960s, late 1990s and millennium were all pivotal – and our current, nostalgic era, perhaps due its fractured and anxious nature, seems to be taken up with them again. Roland Barthes once called these fluid objects ‘a timeless fragmented gazette whose pieces are in a sense the discontinuous significations of a continuous reality’Roland Barthes, ‘La Bruyère, in Critical Essays (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 234. .Scrapbooks' fragmentary qualities subvert the fixity of meaning, allowing them to form subaltern spaces capable of repeatedly deconstructing and reconstructing imaginary heterotopias. This is especially true of artists’ and filmmakers’ scrapbooks. Although they share the same media, this professional group have ‘skilled visions’,Cristina Grasseni, ‘Skilled Visions: Toward an Ecology of Visual Inscriptions’, in Made to Be Seen: Perspectives on the History of Visual Anthropology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 19. to borrow Cristina Grasseni’s term, and they tend to have a more sophisticated understanding of media culture and a greater desire to grapple with it, so their motive in creating scrapbooks feels markedly different from that of people engaged with them simply as a pastime.

Pedro Costa, Caderno (journal) Casa de Lava, 1994 © Pedro Costa

To open these scrapbooks as a viewer is a radically different experience – they invite a curious response somewhere between reading and watching. Although unique objects in their messiness and tactility, scrapbooks are increasingly reproduced in photobook form for readers. Jim Goldberg’s Coming and Going (2023) and Michael Ackerman’s Smoke (2023) both borrow stylistically scrappy elements, but it’s the books of cult filmmakers that publishers have taken a special interest in. Sofia Coppola’s latest publication, Archive (2023), and a reprint of Casa de Lava – Caderno by filmmaker Pedro Costa (2023) were published last year, alongside Les Rencontres d’Arles staging Scrapbooks: dans l’imaginaire des cinéastes, curated by Matthieu Orléan of La Cinémathèque française. Along with being a medium particularly suited to capturing the cacophony of visual thought that goes into producing a film, scrapbooks make explicit the relationship between the still image and cinema, and the creative leaps between the two.

The past, present, and future of cinema can be traced within Edward Muybridge’s scrapbook, at least according to Stephen Barber. In Muybridge: The Eye in Motion (2012), the scholar explores how artists’ scrapbooks and experimental film had a common enemy: mainstream twentieth-century cinema of industrial power, generic character arcs, and staid, linear narratives. He writes, ‘the scrapbook never narrates; it fragments, re-invents and propels beyond narrative.’Stephen Barber, Muybridge: The Eye in Motion (Solar Books, 2012), 11. If cinema is about empathetic movement and photography about mute stillness, what characterises the filmmakers’ scrapbooks I’ll explore in this essay is animation. There’s a sense that the primordial soup of film – the image, criticism, and the imagination – are forming a Frankenstein body destined to move. Images beget images. Costa described the scrapbook as crystallising the moment when the ‘film might think for itself’ and live.Nuno Crespo, ‘“I Died a Thousand Times”: Conversation between Pedro Costa and Nuno Crespo’, in Casa de Lava – Caderno (Lisbon: Pierre von Kleist), 3.

In Europe, the history of the scrapbook dovetails with the histories of paper, publishing, and photography. Early sixteenth-century scrapbooks were compilations of rare printed texts, but by the late nineteenth century, developments in photography and chromolithography meant that the Victorian scrapbook was a means of filtering and processing the deluge of printed material.Katie Day Good, ‘From Scrapbook to Facebook: A History of Personal Media Assemblage and Archives’, New Media and Society 15, no. 4 (2012): 557–573. Premiering in 1895, cinema seemed to blow up just as scrapbooking waned as a popular pastime. But from the 1910s, cinematic promotional materials began to filter into patron Marie-Laure de Noailles’s detailed fan scrapbooks, Francis Stanton’s film criticism, and twentieth-century Hindi cinema scrapbooks as encountered in Filmi Jagat. In their scrapbooks, cinemagoers began to experiment with new forms of spectatorial engagement.

With the rise of mass media in the early twentieth century, artists sought to redefine their position in relation to images, placing less emphasis on the creation of original works and instead engaging as critical consumers first and foremost. Their use of the medium started as a joke: Dadaist collage saw Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque challenge the idea that art stood apart from reality. Using the method’s principles of cutting, pasting, and reassembling diverse materials, they both challenged visual representation and implicated the everyday nature of things. The typographical and visual assemblages unfolding across the advertising techniques of the era became the material of artists and filmmakers both literally and conceptually. In scrapbooks, like in cinema, the creative impulse was to master, manipulate, and edit the overwhelming glut of found and pre-existing imagery being coughed up.

1960s Experimental Cinema: Cut-ups and collage

In 1960s America, experimental cinema worked against representational conventions and produced daring films that tested the medium’s parameters. Stan Brakhage was at the centre of this reinvention. The filmmaker was interested in film’s ability to externalise the pre-linguistic cognitive realm that provides the basis of image-making. Delving into the abstract and non-narrative, the unnamable shapes of dreams that eyes generate through sensations, hypnagogic sparks, and tonal flashes, he developed the term ‘moving visual thinking’Suranjan Ganguly, 'All That Is Light: Stan Brakhage on Film,' Sight and Sound, 1993, https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/interviews/all-that-light-stan-brakhage-film.. As with the scrapbook, this was about immediacy and sensation.

Jane Wodening & Stan Brakhage, Scrapbook de Jane Wodening & Stan Brakhage, 1962-1966 © Jane Wodening, Stan Brakhage – Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale Univeristy, United States

Jane Wodening & Stan Brakhage, Scrapbook de Jane Wodening & Stan Brakhage, 1962-1966 © Jane Wodening, Stan Brakhage – Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale Univeristy, United States

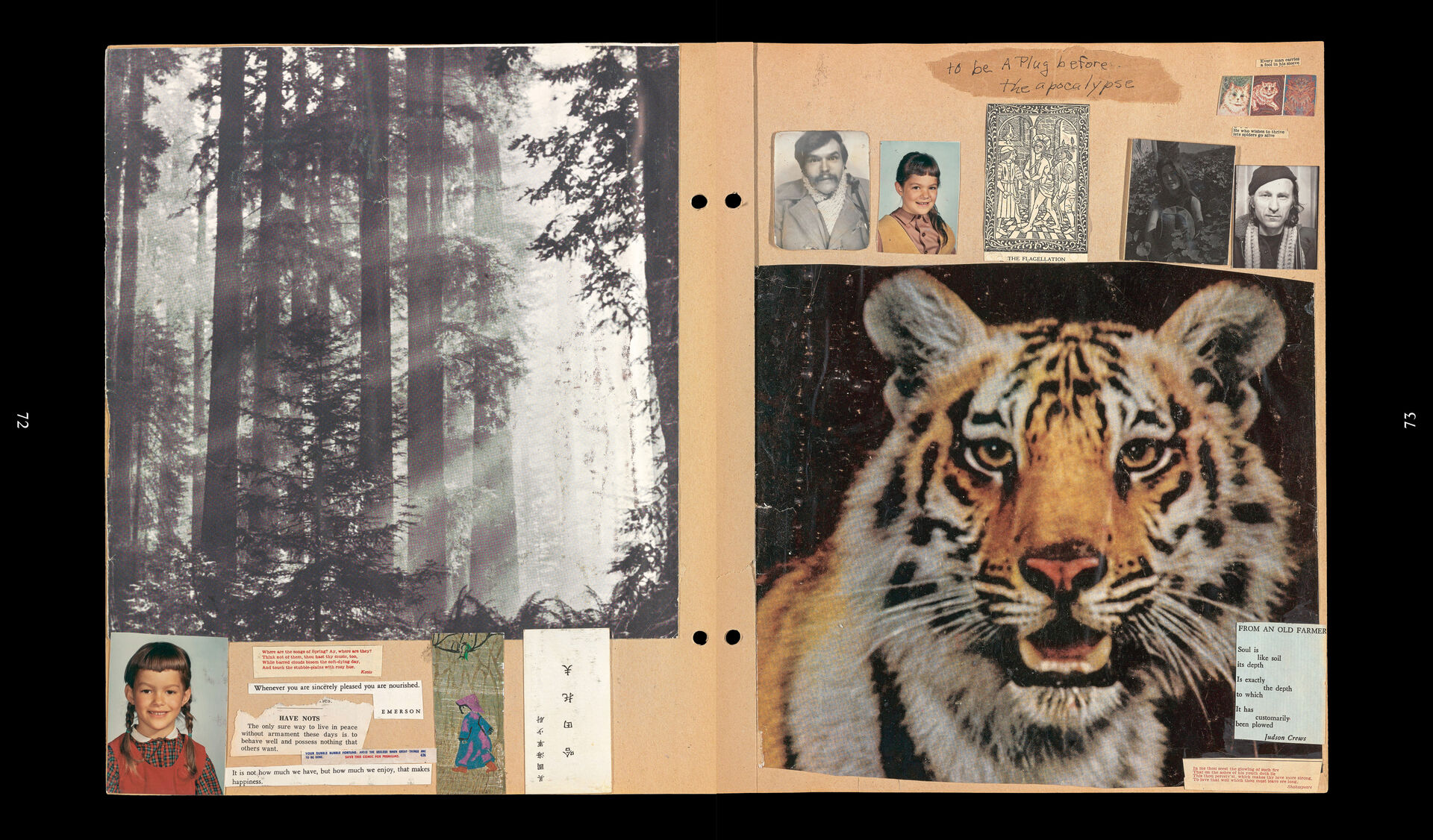

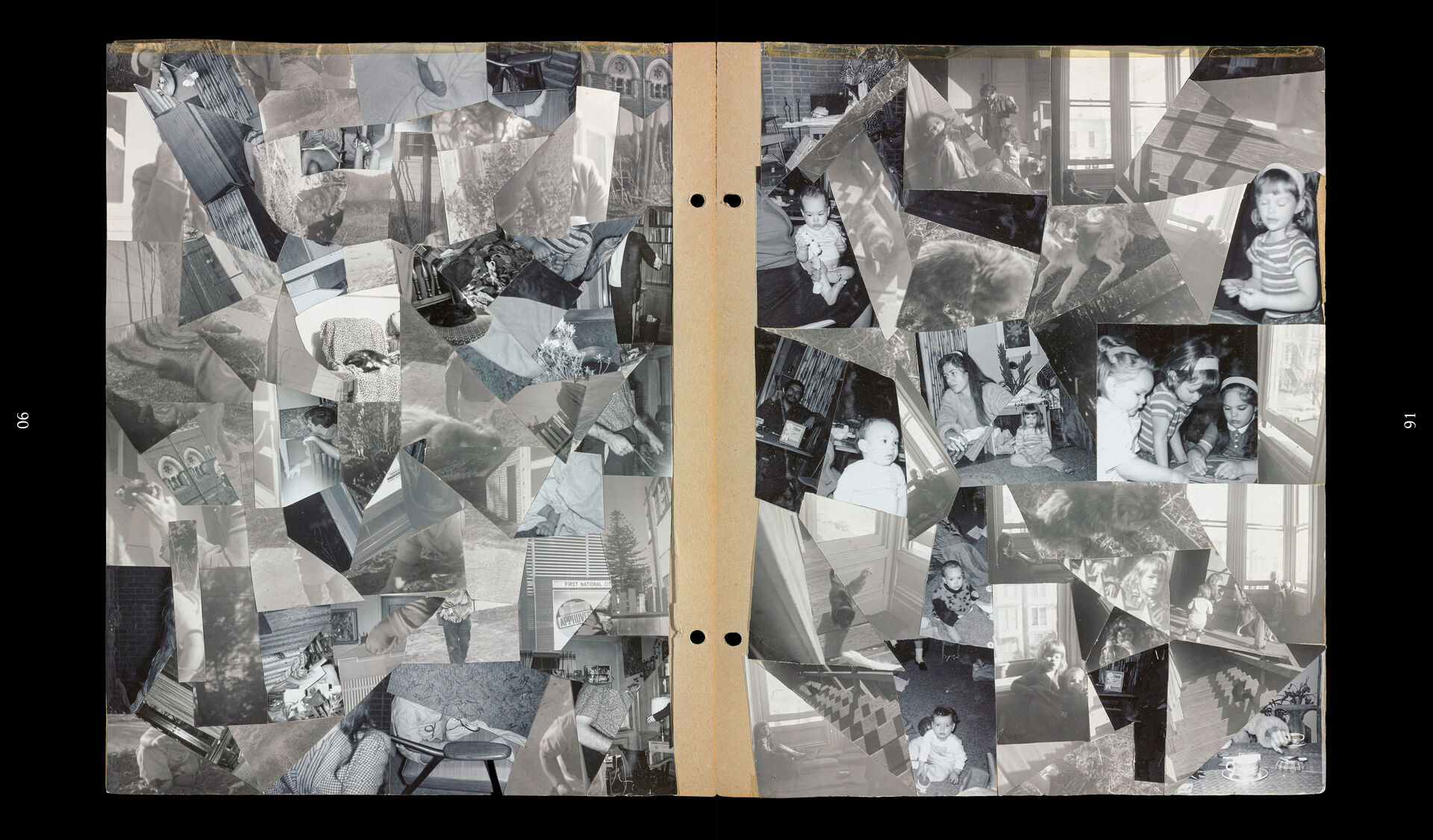

Often filming the family dynamic to picture this thesis, he recognised his marriage to writer Jane Wodening as being vital to his work, stating that ‘By Brakhage’ on his films should be understood to mean ‘“by way of Stan and Jane and all the children Brakhage”’Richard Deming, ‘Collage, Collaboration, and Material Quotation: The Scrapbooks of Jane Wodening and Stan Brakhage, 1962–66’, The Yale University Library Gazette 81, no. 1/2 (October 2006): 34 , though his wife would also have considered herself an artist and writer in her own right. In co-creating the Brakhage universe, Wodening began developing three large scrapbooks, each with seventy-eight leaves of collaged material. While Stan was away lecturing, she worked on them in solitude, seeing them as an outlet outside of the cinematic myth she had (somewhat unhappily) co-created. She’d begun the scrapbooks in the late 1950s as the couple left San Francisco: ‘I remember working on them, page by page, here and there in our travels, at Hooker Street [Denver], in South Dakota, in New York City, and in Lump Gulch [Colorado], people swimming through life like angels.’Selections from the Jane Wodening and Stan Brakhage Scrapbooks, 1962–1966, (New York: Granary Books, 2021). https://t.ly/BNbqk The double pages are traditional in their familial subject matter, but they’re optically immersive and anti-authoritarian in layout. Brakhage despised the ‘man-made laws of perspective or compositional logic’‘Stan Brakhage’s Metaphors on Vision’, Harvard Film Archive, October 13–November 11, 2017, https://harvardfilmarchive.org... that blighted one’s ability to see. Within the pages of Jane's scrapbook, the domestic sphere becomes tangled and layered, with scraps of family snapshots, postcards, folksy animal stamps, letters, Gaia imagery, and Xerox artwork, all arranged in a spectral immersion that leaves the reader trapped in the visual family dynamic.

As poet Richard Denning writes, the scrapbooks make palpable Brakhage’s belief ‘that an artist was an instrument for a “larger creative force”, a force that does not just move through him but the family milieu and the intensity of its intrinsically multivalent relationships’.Deming, 34. In one spread of a swirling multi-perspectival collage, children are pictured at different ages, in different locations, as the domestic interior becomes the exterior street in a topological surface where time and space have contracted and stretched. It’s the mother’s perspective: children, everywhere, all at once. At times, tactile activity is needed to approach the scrapbook, with the reader unfolding and refolding the pasted images, discovering hidden images, the meaning lying inside and outside what could be described as a Deleuzian desire to live in the folds.French philosopher Gilles Deleuze's way of describing how the outer world is folded, and folded, until an interior one emerges. Denning notes that ‘the scrapbooks served as Wodening’s way of taking the art of their lives and relocating it.’Deming, 36. Perhaps this is why she pasted so many family photographs into them.

Incorporating both medium and method, Brakhage’s first cameraless film borrows from the primitive and labour-heavy cut-and-paste art of scrapbooking. Produced the year after Wodening began scrapbooking, Mothlight (1963) employs its formal collagist approach by using organic matter, moth wings, flowers, seeds, leaves, and blades of grass, sandwiching these between two layers of clear sixteen-millimetre Mylar tape. Indeed, on a double page of the scrapbook, Wodening literally pastes herself into the film’s origins by glueing down a portrait of the pair creating said Mylar film strips. The material and sensual aspects of the collage and scrapbooking approach were formed in tandem with Brakhage’s film, but somehow the scrapbook became everything the film could not contain.

In the 1960s, scrapbooking became popular among artists who saw it as a marginalised, minoritarian practice that could be used for resistance and cultural transgression. Between 1963-4, William S. Burroughs began the first of his ‘layout books’. He had been experimenting with the ‘cut-up’ method, as influenced by his collaborator Brion Gysin (who himself had drawn inspiration from the Dadaist Tristan Tzara, to whom the method is owed), a style of splicing pre-written material and rearranging it. The author felt the cut-up method could break out of staid narrative and reveal the instability of words, images, and other carriers of meaning. His earliest scrapbooks are a form of image analysis drawn from media codes, as one late-1960s scrapbook responding to Marshall McLuhan’s observation that ‘the medium is the message’ suggests. Filled with news clippings that chart student riots to anticolonial movements erupting across the decade, it is cheekily titled 'The Order and the Material IS the Message'Alex Wermer-Colan, ‘The Order and the Material Is the Message’,American Book Review 41, no. 3 (2020): 7. .

As Alex Kitnick notes in his essay ‘Paper and Cuts’, Burroughs was invested in understanding the contiguities of imagery in magazines and in the wider media landscape.Andrew Roth and Alex Kitnick, Paperwork: A Brief History of Artists’ Scrapbooks (London: Andrew Roth, PPP Editions, 2013). Charting a topological twist, in one scrapbook, Burroughs pastes a clipping about evangelist Billy Graham and notes on its backside, ‘is the hand of a Watergate judge with a wrist watch’. Underneath, he glues a picture of an Omega wristwatch. A question mark hovers above it, and a note appears: ‘On the back of this watch Israeli [sic] fighter planes shooting down Libyan passenger plane 727 Ref. pages 65, 66, 67 Scrap Book J.B.’

Later, in his famous interview with The Paris Review, Burroughs concluded:

I’ll read in the newspaper something that reminds me of or has relation to something I’ve written. I’ll cut out the picture or article and paste it in a scrapbook beside the words from my book. Or, I’ll be walking down the street and I’ll suddenly see a scene from my book and I’ll photograph it and put it in a scrapbook. . . . In other words, I’ve been interested in precisely how word and image get around on very, very complex association lines.William S. Burroughs, ‘The Art of Fiction No. 36’, The Paris Review 35 (1965).

Burroughs felt that this close attention to the culture of media images, when rearranged and collaged, would reveal the interplay between external observations and internal reflections. ‘When you cut into the present, the future leaks out’, he would say of his method.‘Cut-Ups William S. Burroughs’, 2011, YouTube video, 3:14, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rc2yU7OUMcI. The cycle of media, its perpetual narratives and discourses, were laid out in plain terms.

Burroughs’s concept of the unconscious aligned with changing ideas of the period. In the 1960s, the Situationist movement had steered the idea of the unconscious as a deep internal state that had to be delved into by Surrealist means toward a concept of a collective unconscious, as reflected in the ‘technological dream state of cinema’ from which we had to wake up.David Campany in conversation with John Stezaker, ‘Seams and Interruptions: Surrealism and Photography’, Frieze Masters no. 2 (2013). Burroughs’s filmography includes two experimental films co-directed with Antony Balch in the ’60s. Following his experiments with scrapbooks, in The Cut Ups (1966), he and Balch carried the radical cut-up composition into the editing process itself, intending to mimic conscious thought built out of creative associations and revelatory patterns in a visual form of thinking.

The act of paper collage was a way to oppose narrativisation. For both Wodening and Burroughs, the everyday and mundane qualities of the material media could be conjoined to outwit the connections, interferences and resonances of images that governed daily life. This is not unlike the Surrealist experiment with collage in the 1930s, which relied on found materials of disparate and unfamiliar realities to create sparks of memories and associations. Max Ernst brought collage into Surrealism. In La Femme 100 têtes (1929), one of three novels without text that he produced, the artist collaged images from nineteenth-century wood engravings in popular novels, books on the natural sciences, and engraved reproductions of art works, in an illogical series of disruptions and conjunctions that collapsed histories. Collage became less about the pictorial and more about the subversion of narrative and the challenging of formalities of plot and character. André Breton, obsessed by the cinematic qualities of Ernst’s collages, expressed how they could ‘disorient us within our own memories by removing our systems of reference’.Abigail Susik, ‘“The Man of These Infinite Possibilities”: Max Ernst’s Cinematic Collages’, Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture 1 (2011): 68. Ernst took great care to create seamless images, concealing the sutures between units, to emphasise the final image’s reality, much as film did with its illusory twenty-four frames per second. The eye is tricked. It’s distinctly cinematic, this combination of edited images and sequences of disparate realities, running together into one smooth narrative thread.

The French New Wave: Experiments in still photography

In Europe, French New Wave filmmakers were also indebted to the scrapbook, but used it more to explore the significance of the still image. In the post-war period, Deleuze argued that cinema shifted from the movement-image – cinema as moving through successive images that follow a narrative, perceptive logic – to the time-image, whereby filmmakers explored non-linear, complex conceptions of time. Through editing techniques such as cutting, montage, and repetition, Deleuze showed how time became an active agent that shaped cinema and equally resonated outside of it.Marion Schmid, ‘Still/Moving: Photography and Cinematic Ontology’, in Intermedial Dialogues: The French New Wave and the Other Arts (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

Agnès Varda was a collagist (and in her later film The Gleaners and I (2002), a decidedly feminine bricoleur), in both the form and content of her filmic work. But her early cinema was deeply indebted to her studies in photography and the history of art, and her portraits and street photography complemented her cinematic way of apprehending the world. Varda’s 1962 scrapbook, an album that uses film as a mirror for her marriage to the director Jacques Demy, shows her continued interest in gaze, gesture, and the expressive body through time. The searching face had a particular draw for the director.

Agnès Varda, Scrapbook made and offered by Agnès Varda to Jacques, Demy for Christmas 1962 © Estate of Agnès Varda and Jacques Demy

The September after their marriage, Varda visited her new husband on the set of La Baie des Anges (1963). Afterward she would present him with a tokenistic scrapbook compiled with the photographic film stills she took while in his company. ‘Story of my life’, a glued newspaper headline reads. The following pages assemble the personal and the professional in a collage of newspaper text, ticket stubs (Varda’s and Demy’s cut-out faces overlaid), film still photography, snapshots, and folk illustrations glued into a purchased photography album with pre-cut slits. Stills of blonde starlet Jeanne Moreau and Claude Mann are arranged into the album in a way that is suggestive of jump cuts. A photograph of Demy is playfully stuck above a still of Moreau looking upward, overlaid with a biblical quotation from The Apocalypse of St. John the Apostle and dotted with kitsch mediaeval angels. Varda treats time expansively in revealing unexpected synchronicities across periods, reverberating echoes of the past within the present, and blurring of the fictional with reality in a subjective twist. In her characteristic flair, Varda's scrapbook commentary re-arranges still photography and souvenirs to implicate her director–husband within the mechanics of the film whilst mirroring their own marriage. Turn the page and the couples (on-screen and off-screen) are reunited within a single image, closing the chapter on the shared idyll of romance.

Although he didn’t create a scrapbook per se, it could be argued Jean-Luc Godard thought like a scrapbooker in his expansive genius. Both American writer Richard Roud and American critic and intellectual Susan Sontag commented on Godard’s aggressive use of the jump cut in À bout de souffle (1960) as bearing similarities to the Cubist conception of collage modelled by Picasso and Braque. In his later films Une femme mariée (1964) and 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle (1966), Godard continued exacting the relationship between jump-cuts, montage and collage. He developed two techniques found in both films. The first being collage through montage, whereby he spliced together shots of disparate elements; secondly, filmic collage through layering of mise-en-scène within the frame. For example when a superficial woman in Une femme mariée (1964) stands directly in front of her aspirational busty billboard advertisement. ‘Montage as collage resembles classical Cubist practice in its reconstruction of a meaningful whole from fragments in the cutting-room’, writes author Douglas Smith, ‘Mise-en-scène as collage, on the other hand, records the juxtapositions proposed in front of the camera.’Douglas Smith, ‘(Dé)collage: Bazin, Godard, Aragon’, in A Companion to Jean-Luc Godard (John Wiley and Sons, 2014), 215.

Collage had been somewhat random but involved creating new perspectives, while montage emerged as the precise and controlled incorporation of the cut fragments into dialogue with each other. The term ‘montage’ stems from the French monter (to assemble); in film, it is used for editing and differs from collage in the greater emphasis it places on juxtaposition – a technique often used to create clear meaning and messages for the audience.

Scrapbook made for the film Shining. Courtesy SK Film Archive LLC, Warner Bros and University of the Arts London, United Kingdom

Chris Marker started out in life as an editor. One of his formative roles, at thirty-three years old, was as the editor of Les éditions du Seuil’s collection of travel guides, Petite Planète, between 1954 and 1958. ‘Not a guidebook, not a history book, not a propaganda brochure, not a traveller’s impressions, but instead equivalent to the conversation’, he said of the guides, later calling the slim books ersatz cinema.Isabel Stevens, ‘Isabel Stevens on Chris Marker’s “Petite Planète”, Aperture, August 4, 2020, https://aperture.org/editorial...; A press shot of Audrey Hepburn on the set of Sabrina (1954) appeared in Petite Planète 4: Hollande, thought to be a reference to her support for the Dutch resistance against the Nazi occupation in World War II. A volume on Greece reveals a page of reproduced images: an ancient Greek vase, a panel from an unattributed comic strip, and a still showing Kirk Douglas and Silvana Mangano in Mario Camerini’s Ulysses (1954), arranged as if in a montage. What this did was begin to develop a method that highlighted historical parallels, analogies, and correspondences of national narratives.

When the Cinémathèque française discovered his sketchbooks in 2012, the organisation found that they contained spreads of reproduced illustrations and artworks that mirrored the eclectic gathering of materials similar in effect to the travel guides. Pavel Tchelitchew’s Spiral Head series (1950) and the tropical surrealism of Wifredo Lam’s The Antillean Parade rub up against images of the Ku Klux Klan, a 1940s magazine ad for Revlon cosmetics, and surrealist photography. An entire double page is devoted to women, one of Marker’s recurring fascinations, including celebrity portraiture of Lucille Ball and Nina Leen’s female subjects from LIFE magazine; all have their eyes blocked out. Creating visual synergies between mass-produced contemporary and historical images and between low and high culture, and working across mediums, Marker references Dadaist photomontage and surrealist collage, the latter in their creation of ‘poetic and aesthetic shock[s]’ of unfamiliar associations.

When we compare the printed material to the films Marker produced in the 1950s, we can see how the page begins to unfold across the screen. Olympia 52 (1952), a documentary film about the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki (an event that Marker didn’t necessarily have access to) uses montage to bridge connections and highlight multiple, intersecting politico-historical narratives. One montage sequence shows footage of the angelically-dressed West German activist Barbara Rotraut Pleyer interrupting the games as a political stand against the 1950s Korean War and the threat of a possible third world war she felt on the horizon; in the next, Marker cuts to a reference to the games’ ancient Greek origins, then to Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary Olympia (1938); later, he cuts to a Swastika flag. The contemporary is interrupted by historical phenomena of the more distant past, in what Husserl describes as the thickening of the present.

Notably, the scrapbooks are composed of black pages (similar to an artist’s sketchbook) that share the characteristic black leader of Marker’s films. The ‘dark rooms of museums’, to quote a voiceover from his film manifesto Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (1966), or those found in the virtual museum of Ouvroir (Second Life Workshop), seem to unfold on the page. Less the traditional, messy collage of other filmmakers’ scrapbooks, each image is pedantically cut around the borders and given ample room on each page with zero overlap, giving the impression that Marker has a special reverence for the content and form of the image in and of itself. One or two have been glued to the book and bear the marks of the pins with which they were once attached to a wall. In the dark of the scrapbooks, Marker forms a musée imaginaire, as defined by André Malraux, storing images unbound by time or space in the memory bank of the mind’s eye. Like his other works, the scrapbook functions as a stream of consciousness that no longer differentiates between objectivity and subjectivity, or past and future – his distinct style persisted in whatever media he touched, from film to video to digital.

John Truwe, Scrapbook #1 © John Truwe papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills, United States

New Wave filmmakers like Varda, Marker, and Godard would continue their relationship to collage as a technique throughout their working lives, whatever medium they engaged with. In the late 1980s, Godard began work on his monumental Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–1998), an epic intertextual collage that relies on fragments of media, sound, films, newspaper clippings, paintings, drawings, and other overlapping images to tell the history of cinema, cycling through its role in the twentieth century. Much like Ernst’s Surrealist collages as characterised by Breton, Godard’s eight-part video collage montages through ‘bold and irreverent redistribution of the combination of competing sign systems’ that produce what is not there or ‘what simply exists in an intangible, unactable way’.Angela Dalle Vacche, Cinema and Painting: How Art Is Used in Film (London: Athlone Press, 1996), 111–114. In blending disparate forms, from the content of 1920s Soviet films to the work of Van Gogh to images of the Holocaust, among many other themes, the films adopt a polyphonic nature that endlessly quotes architecture, the history of art, world literature, music, and theatre. Beyond criticism or interpretation of images, Godard shows us how we think and feel with them. Considered a director of essay films, he reflects in Histoire(s) du cinema that the documentary is a ‘thought which forms a form that thinks.’ And thinking with images is partially about montage.

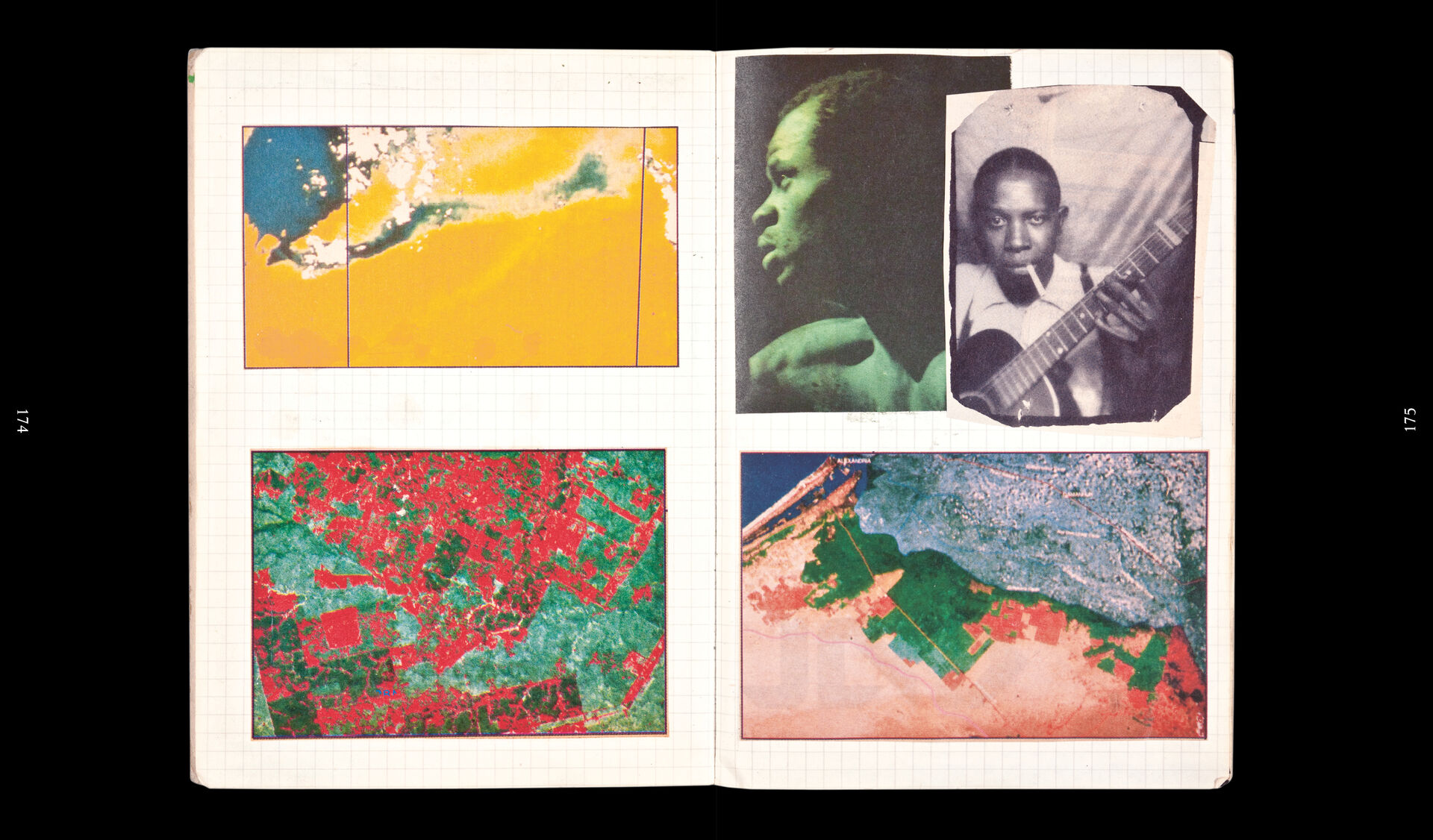

1990s: Literature Without Literature

Signs are ‘mysteries’ for Portuguese director Pedro Costa. Costa’s second film, Casa de Lava (1995) is a ghost story that begins when a young nurse arrives in Cape Verde with a comatose Black labourer injured in an accident, but realises she has inadvertently brought a living man to the island of the dead. Costa had first arrived on the volcanic island in 1993, armed with a caderno (notebook) that was originally intended for production notes but quickly morphed into a scrapbook when he began glueing portraits of women from a local village, Chã das Caldeiras, into it.

Scanning the scrapbook is an exercise in spotting the explicit quotes. The ‘notebook’, as Costa called it, layers stills of his lead actress, Edith Scob, in Georges Franju’s Les yeux sans visage (1960) alongside other historical film references, and overexposed, slightly sun-bleached, ghostly photographs taken of women from Chã das Caldeiras are glued down as if they stare at something outside the page, moved by the external world. The film’s opening sequences are revisited by these expressionless apparitions, as we are not granted the opportunity to see the object of their gaze.

There is also a less obvious technique at work within the scrapbook’s pages. A printed postcard of Picasso’s Maternité (1905) sits in conversation with a photograph of a young Cape Verdean mother; a photograph of Isaach de Bankole, the bricklayer Leão in the film, is positioned next to a photograph of a very frail Lenin at the end of his life. Both are wheelchair bound. Costa felt that the networks of echoes, resonances, and rhythms between images developed a ‘third idea’, much in the vein of Godard. Images do not explain a defined fact but rather instigate more questions in their proximity to one another.

Derek Jarman, Derek Jarman Papers, Carnet Jubilee, Carnet Sebastiane, Carnet The Last of England © Keith Collins Will Trust – Courtesy BFI National Archive, London, United Kingdom

Despairing over the inadequacy of the rhetorical film script, filled with technical instruction, Costa wanted to develop emotional resonances that would invite a sensitivity to text and image. ‘You don't make cinema with images any more than you write a poem with poetic words’, he noted. ‘I needed something that was literary, but that wasn't literature.’Carla Henriques, ‘Entrevista Pedro Costa’, Pedro Costa – Entrevista, Artecapital.art, https://www.artecapital.net/en.... The result is a collection of newspaper clippings, facts, photographs from magazines, postcards, small fragments of texts or images that have a poetic, allusive quality when augured into a new contextual arrangement. ‘This “writing”, more irrational, affective and very sensitive – was almost like living in an uninterrupted déjà vu’, he observed. ‘This notebook wants to continue, by other means, our cinematographic montage; with postcards and news, with glue and scissors, here we imitate a certain theory and a certain cinematic practice that are unfortunately on their last legs.’Crespo, 5. The scrapbook became so effective in communicating Costa’s vision to the production team that the original script, which was based on Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943), was scrapped. Long after the film ended, Costa continued adding to its pages, as Casa de Lava by itself was never intended to be the final product.

As intermedial and intertextual Frankenstein forms, the filmmakers’ scrapbook is a working book. Burroughs’ scrapbooking ‘cut-ups’ gave him the ability to think in associative blocks rather than words or narrative, which made him vulnerable to a type of cultural complacency. In fragmenting and reordering and making film subject to constant interruptions, he saw new pathways in the everyday. Through careful editing, Marker learned how to fold the historical and future into his present medium through a unified cinematic montage. Costa gathered the external world of the Cape Verdean island into an internal canvas. Collected, caressed, shaped, cut, compressed, or loosened, the materials that passed through the hands of these filmmakers fed their critical imaginations. As Costa stated, cinema isn’t made with images; Ernst similarly claimed that a collage was not made by glue. Filmmakers’ scrapbooks are not about the technicality – they deliver a state of mind. Scrapbooking was a tool to make sense of the overwhelming amount of physical imagery at hand, as a form of criticism that ensured a greater sensitive receptivity, whether emotional or historical, to the work at hand.

SCRAPBOOKS. Dans l’imaginaire des cinéastes, Matthieu Orléan (delpire & co, 2023)

Paris-based publisher delpire & co are exhibiting until 16 March 2024 the second part of the exhibition presented at Rencontres d’Arles 2023, which featured the book of the same name by Matthieu Orléan.