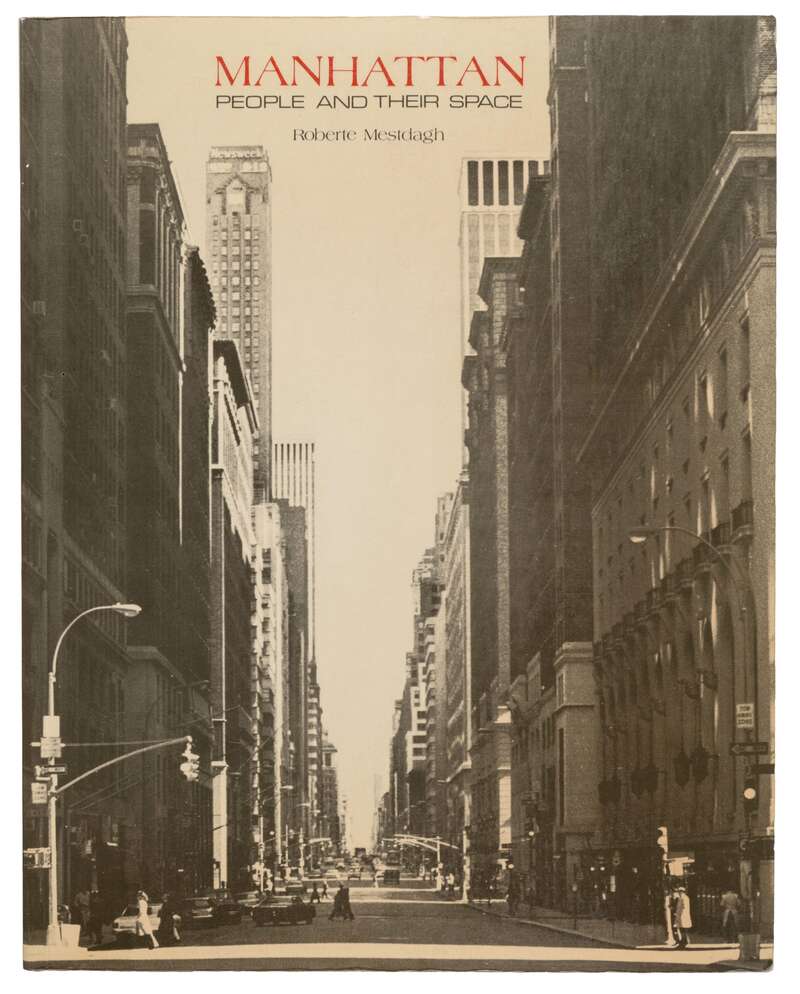

Roberte Mestdagh, Manhattan: People and their space, 1981.

Scanning the City

Editor’s note: In 1981, Belgian artist Roberte Mestdagh published the intriguing photobook Manhattan: People and Their Space. After exactly 40 years, art critic and photo historian Steven Humblet digs this long forgotten and disconnected depiction of a much-photographed city out of FOMU’s collection. Mestdagh’s interest lay in the effects of buildings and the environment on the specific bodies and experiences of Manhattanites. New York was a different city then, but the book’s photographic strategies still resonate today.

Steven Humblet

02 apr. 2021 • 14 min

A Fragile City

In the 1970s, New York seemed like a city on the brink of societal collapse. After losing about half a million manufacturing jobs, the city budget was under constant duress, leading to severe cuts in several crucial departments. When President Gerald Ford refused to come to the rescue, bankruptcy seemed inevitable. Only a last-minute intervention of the teacher’s pension fund diverted the disaster and saved the city from financial ruin.

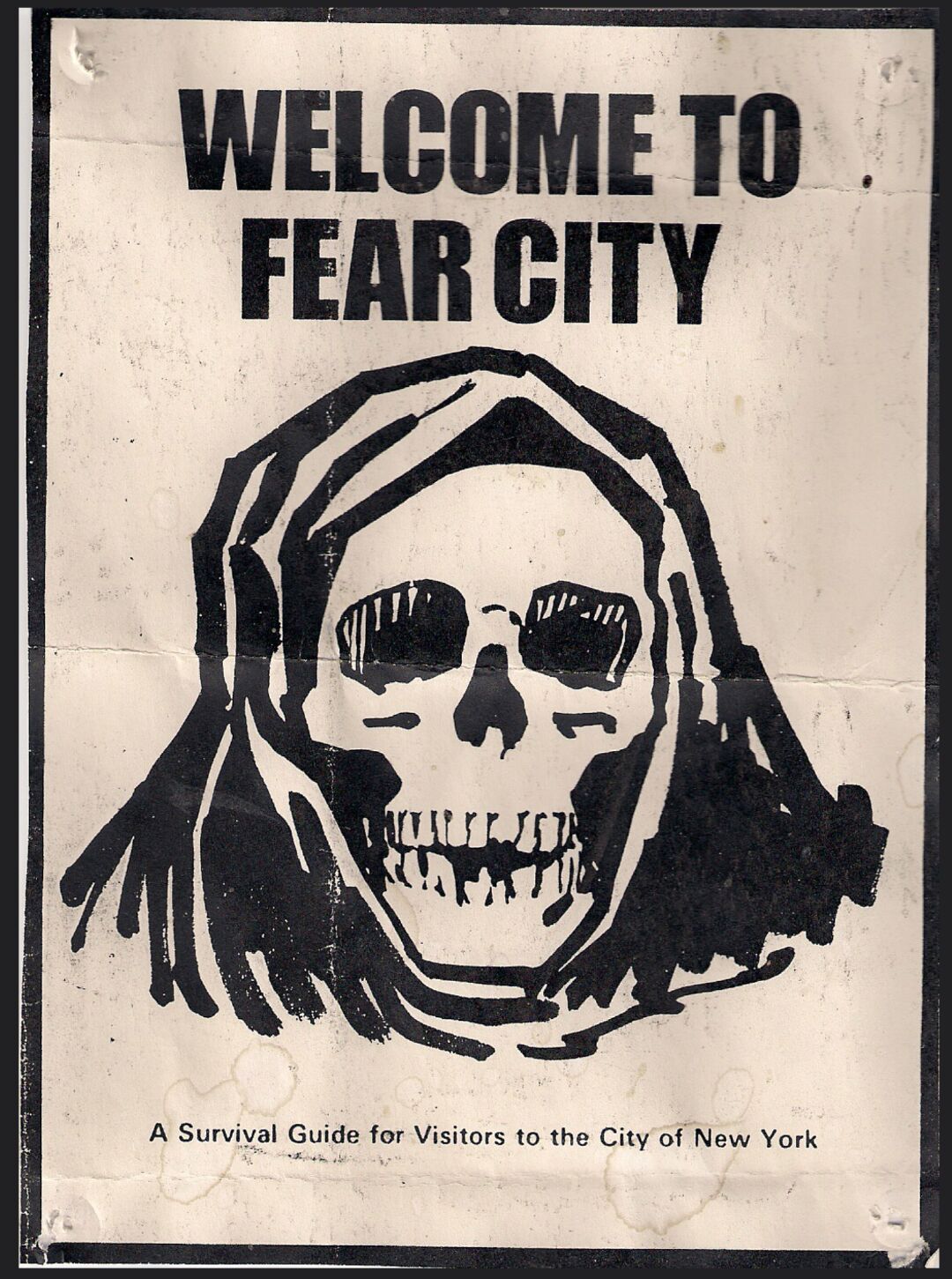

Nevertheless, the financially strapped city struggled to keep the budget under control which weighed on officials’ ability to keep the city in operation. Several hospitals were closed, necessary investments in public transportation systems were postponed or cancelled, the police and fire departments were underfunded and so were schools and sanitation services. With unemployment and poverty on the rise, crime was rampant. In June 1975, visitors arriving at the city’s airports were handed a pamphlet titled Welcome to Fear City. A Survival Guide for Visitors to the City of New York.Kevin Baker, ‘”Welcome to Fear City” – the inside story of New York’s civil war, 40 years on’, The Guardian, 18 May 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/may/18/welcome-to-fear-city-the-inside-story-of-new-yorks-civil-war-40-years-on. On the cover, visitors were welcomed by the image of a hooded death’s head, while on the inside, several tips for surviving their stay could be found. They were encouraged to avoid the outer boroughs, not to venture outside after six in the evening and certainly to never, ever use the subway. They were also warned to hold their bags with two hands and never leave anything in their hotel safe, as burglaries there were supposedly widespread. Of course, the situation was not as dire as the leaflet suggested; more hyperbole than an objective description of the city’s security situation, it was published and distributed by members of the police force, and their aim was to pressure city hall into meeting their demands for higher wages.

Losing so many manufacturing jobs also had a visible impact on the city fabric. Whole areas that were once teeming with small manufacturers had emptied out, leaving vast wastelands in their wakes. However, these abandoned workshops and derelict warehouses provided new opportunities for struggling artists to find large and affordable spaces in which to live and work. Artists and galleries alike quickly moved in, turning these places into hotbeds of artistic creativity. SoHo would become one of these booming arts districts. And yet, at the end of the decade, it fell victim to further gentrification, which forced out artists and lured in more affluent young people. Not all neighbourhoods were similarly able or lucky enough to successfully reinvent themselves. Whereas the deserted SoHo could be recast first as a contemporary arts scene and later an area of high-quality shops, the Bronx failed to transform. The borough north of Manhattan was already torn apart by the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, conceived of and initiated by Robert Moses in 1945 and finished in 1963. The broad motorway, connecting the city to its hinterland, cut aggressively through the Bronx, effectively bisecting it and, in the process, destroying a vibrant community of mostly African American inhabitants.For a description of the havoc caused by the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, see the last chapter in Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity, (New York: Penguin Books, 1982 [1988]), 290-312. The economic crisis of the 1970s, with its massive layoffs, rising poverty and subsequent crime, did the rest. The results were blocks and blocks of ruins, making the area look like a war zone. Fires raged almost daily, often lit by the owners of dilapidated and effectively worthless buildings who were hoping to receive at least some money from insurance companies. Often, the fires would rage for several days, unable to be put out by an understaffed fire brigade.

Ikko Nakahara, Cedar Street, 1973.

An Outsider View

This is the New York in which Belgian artist Roberte Mestdagh stayed from 1977 to 1980. The following year, she publish Manhattan: People and Their Space, a photobook in which she examined the different experiences of people living in the borough of Manhattan. It was an interesting moment for new and exciting photobooks about New York. The city’s bad reputation made people curious, while the arts boom lured artists and photographers from all over the world who were excited to be part of a vibrant community.

More importantly, these foreign photographers introduced new sensibilities to photographic depictions of the city, and they were more daring and experimental than their American peers. American photographers capturing the urban blight of New York during that period stayed firmly within the framework of established documentary practices. One can think of, for example, Danny Lyon’s The Destruction of Lower Manhattan,Danny Lyon, The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, (New York: Macmillan, 1969; New York: Aperture, 2020). Philip Trager’s architectural photographs of 1970s New York,Philip Trager, New York, (Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 1980). Philip Trager, New York in the 1970s (Germany: Steidl, 2016). Bruce Davidson’s social documentary on East 100th StreetBruce Davidson, East 100th Street, (New York: Harvard University Press, 1970; New York: St. Ann’s Press, 2003). and his later series on the New York subway.Bruce Davidson, Subway, (New York: Aperture, 1986; New York: St. Ann’s Press, 2004). In contrast with these approaches stand the formally inventive photographs of Japanese photographers like Ikko Narahara, who visited from 1973 to 1978 and photographed all Broadway intersections between Bowling Green and Columbus Circle with a 180 degree lens before finally assembling them in a mandala-like fashion,Ikko Narahara, Broadway, (Tokyo: Creo Corporation, 1991). as well as Daido Moriyama’s dark and gritty images taken during a visit in 1971.Daido Moriyama, Another Country in New York, (New York: self-published, 1974; Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa Publishing, 2013). Both broke radically with the standard documentary style, offering a new approach to and a more personal vision of the city. Mestdagh’s book clearly aligns with these more avant-garde attempts.

As the subtitle of the book already suggests, her approach to depicting the city was influenced by the notion of psychogeography, a concept coined by French situationist Guy Debord. Her aim was to show the interdependence of the built environment and the mindsets of its inhabitants. The book is structured in 13 chapters, each dealing with a specific neighbourhood in Manhattan. Contrary to standard photobooks on New York, Mestdagh doesn’t start in the most southern (and oldest) part of the city but uptown in East Harlem. From there, she ventures south down to Wall Street and then shifts slowly to the West Side, to Tribeca and SoHo before eventually arriving in Greenwich Village; after that, she climbs back up to Morningside Heights and West Harlem. Each chapter contains conversations with one to three people living in these neighbourhoods. The conversations revolve around the same three questions: how do they experience the place they live in, from their living quarters to their immediate surroundings? How do they behave on the streets of New York, and how do they experience the daily rhythm imposed by living in the city? The people she talked to had different racial and cultural backgrounds, and occupied different jobs, although a majority belonged to the arts scene. Some were born in New York, but most came from elsewhere. In each and every case, the texts reflect people’s mixed feelings about living and working in the city. The tension revolves mostly around the immense pressure the city exerted on its residents: the combination of cramped living conditions with a hostile environment outside the house, a sphere defined by an unforgiving rhythm, often led to people feeling disconnected from the other souls inhabiting the city and sometimes even triggered an excruciating loneliness. Taken together, the texts don’t paint a pretty picture.

On the Street

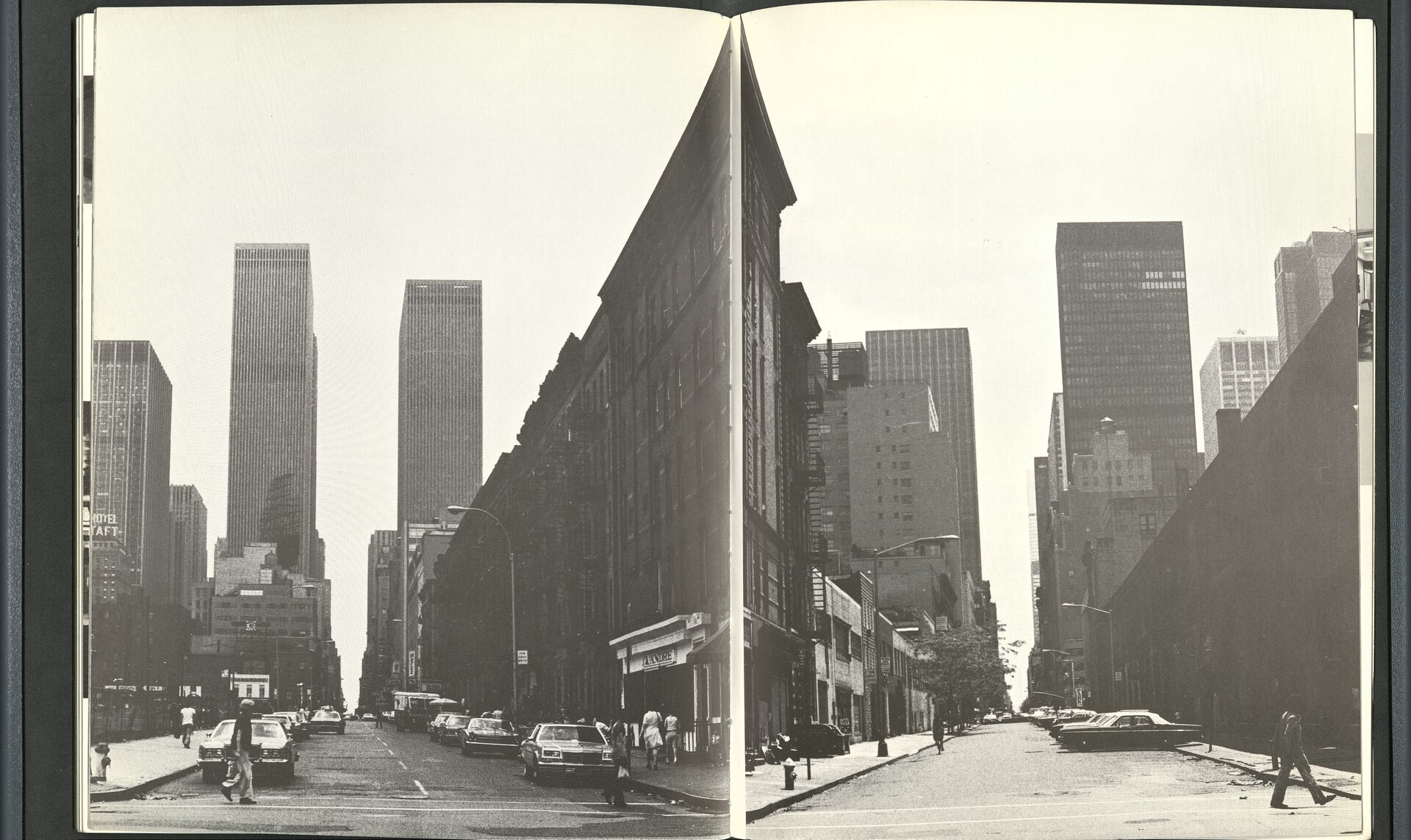

To understand Mestdagh’s focus on the built environment, it might be important to first list what the book doesn’t show. Besides one 360° panorama of Central Park, there are no real traces of the other (large and small) parks that dot New York; there’s no image of Madison Square or Bryant Park, for example, and no images of the riverside near Bowling Green. Also missing are images that focus on the most iconic buildings or monuments; there are no pictures of the Flat Iron, Brooklyn Bridge or Empire State Building. The only exception is a series of images showing the then-recently constructed World Trade Center (finished in 1973) towering over everything else in the Lower West Side. Further, Mestdagh seldom entered the living or working spaces of the people she came in contact with. When she did, the way she addressed these interiors reveals a lot about her true interests. In the two panoramic images taken from inside, there is an outspoken focus on the windows looking out on the city. Interiors interested her only in so far as they related to public space outside. Finally, for a photobook that aims to show the relationship between the human body and the environment in which it dwells, the lack of what we normally consider street photography is somewhat strange. In some images, we see people wandering about or gathering in large groups, but their presences are always subsumed by the imposing buildings around them. Instead, Mestdagh focused on the thoroughfares that structure the city plan.

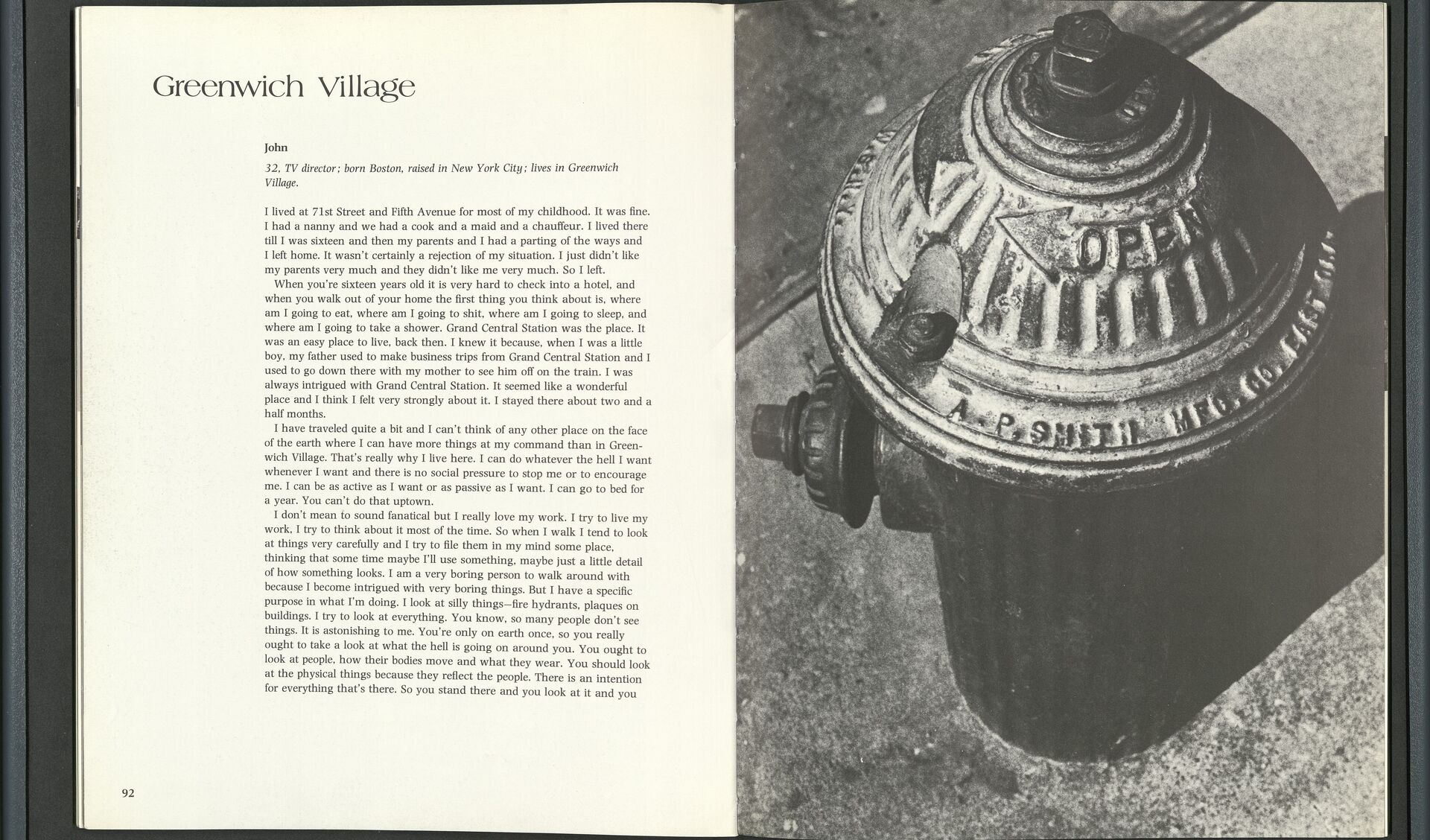

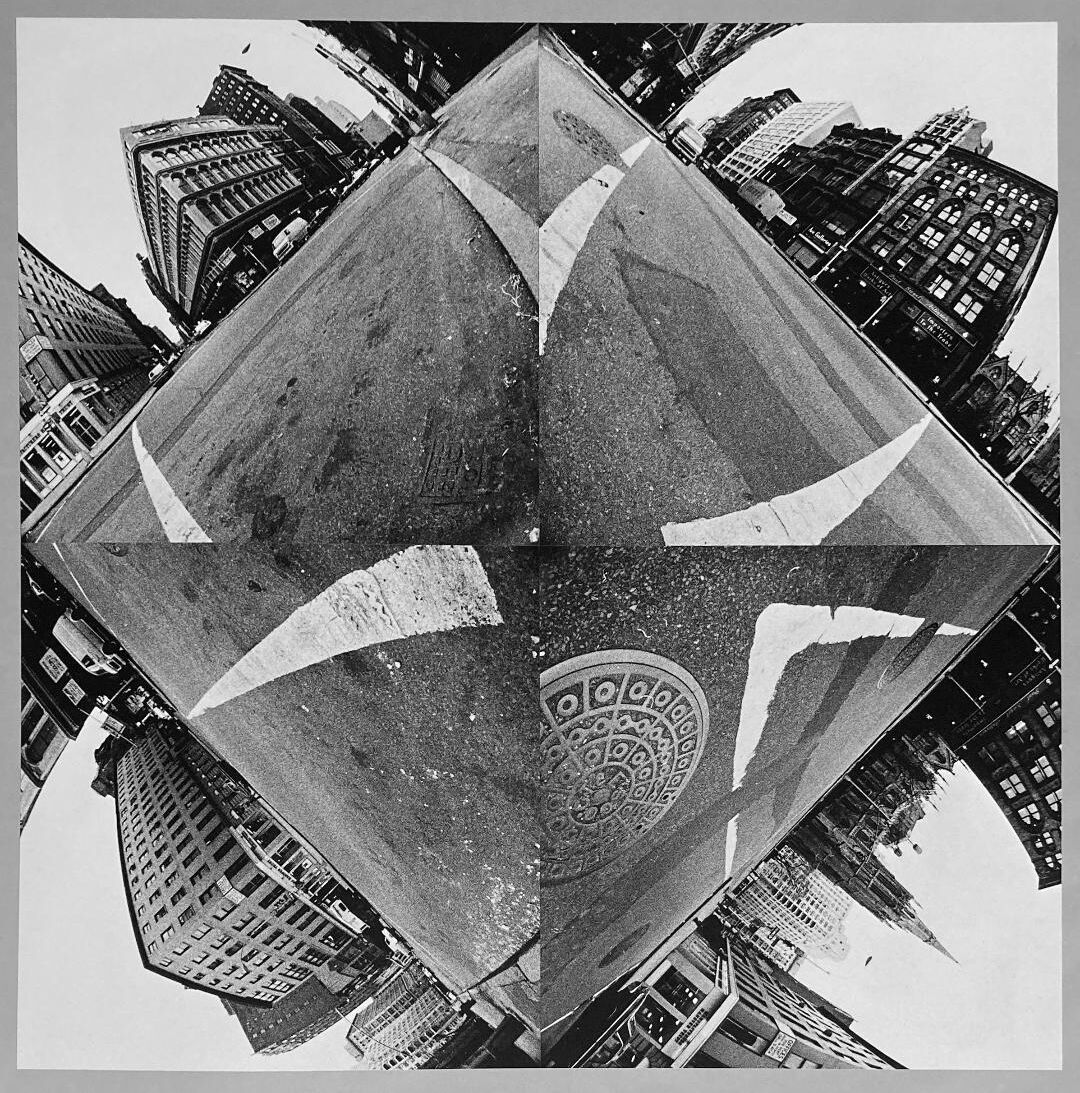

Mestdag’s primary interest in the streets and avenues made sense for someone trying to capture the emotional and psychological effects of the urban environment on its inhabitants. It’s in the daily commute between home and work, in the promenades on the weekend and in the spaces shared with other citizens that the material city exerted its biggest influence. In the book, Mestdagh developed a particular way of addressing this shared space. Instead of presenting her own idiosyncratic understanding of New York, she tried to render the city through the eyes of the individuals she interviewed. This explains the double function of the book’s text: it not only offers verbal information about the personal experiences of the people Mestdagh talked to, it also functions as a tool to direct her gaze. She wedded her camera to her subjects’ visions and to their way of dealing with the hubbub of city life. One brief example: John, a TV director living in Greenwich Village, mentioned that he was often intrigued by particular objects that his fellow citizens took for granted, and he could sometimes even be found studying them up close for long periods. In the images immediately before and after that text, Mestdagh injected close-ups of two of those objects, one of a fire hydrant and the other of a manhole cover.

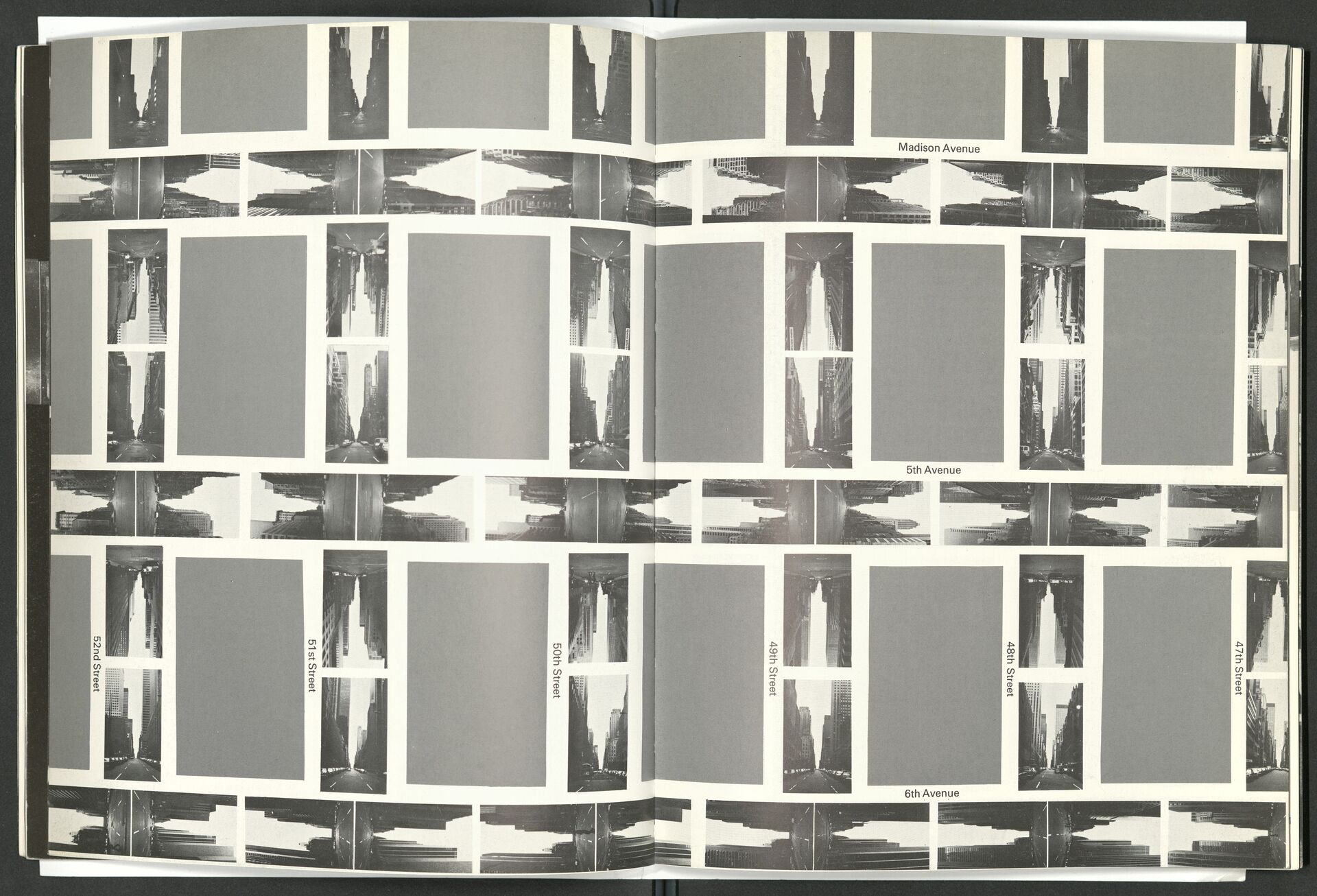

This example is a rather straightforward illustration of how Mestdagh locked her photographic strategy to the visual experiences of others. But it also happened elsewhere, albeit less directly and in a less immediately readable way. One particularly interesting example of this can be found in a pair of spreads that presents part of Midtown New York. These two spreads combine a graphic rendering of the street plan with photographs of every intersection in the area between Madison Avenue and 6th Avenue and between 42nd Street and 52nd Street. In each instance, Mestdagh employed the same strategy. Standing in the middle of the crossroad, she aimed her camera in one of four directions: north, south, east or west. As prints on the double page, these photographs are quite small, rendering them almost indistinguishable. In the end, this leads to a situation in which all images, all street views, look similar. The lack of clear points of reference (be it specific buildings or monuments) makes it difficult for readers (and pedestrians alike) to find their bearings in such a confusing labyrinth. The grid-like street plan was originally conceived to make the city more readable, but here, it has the opposite effect of turning it into an impenetrable maze. As such, these spreads seem to reflect the sense of loss, of disconnection, that several people expressed in their interviews.

Looking Around

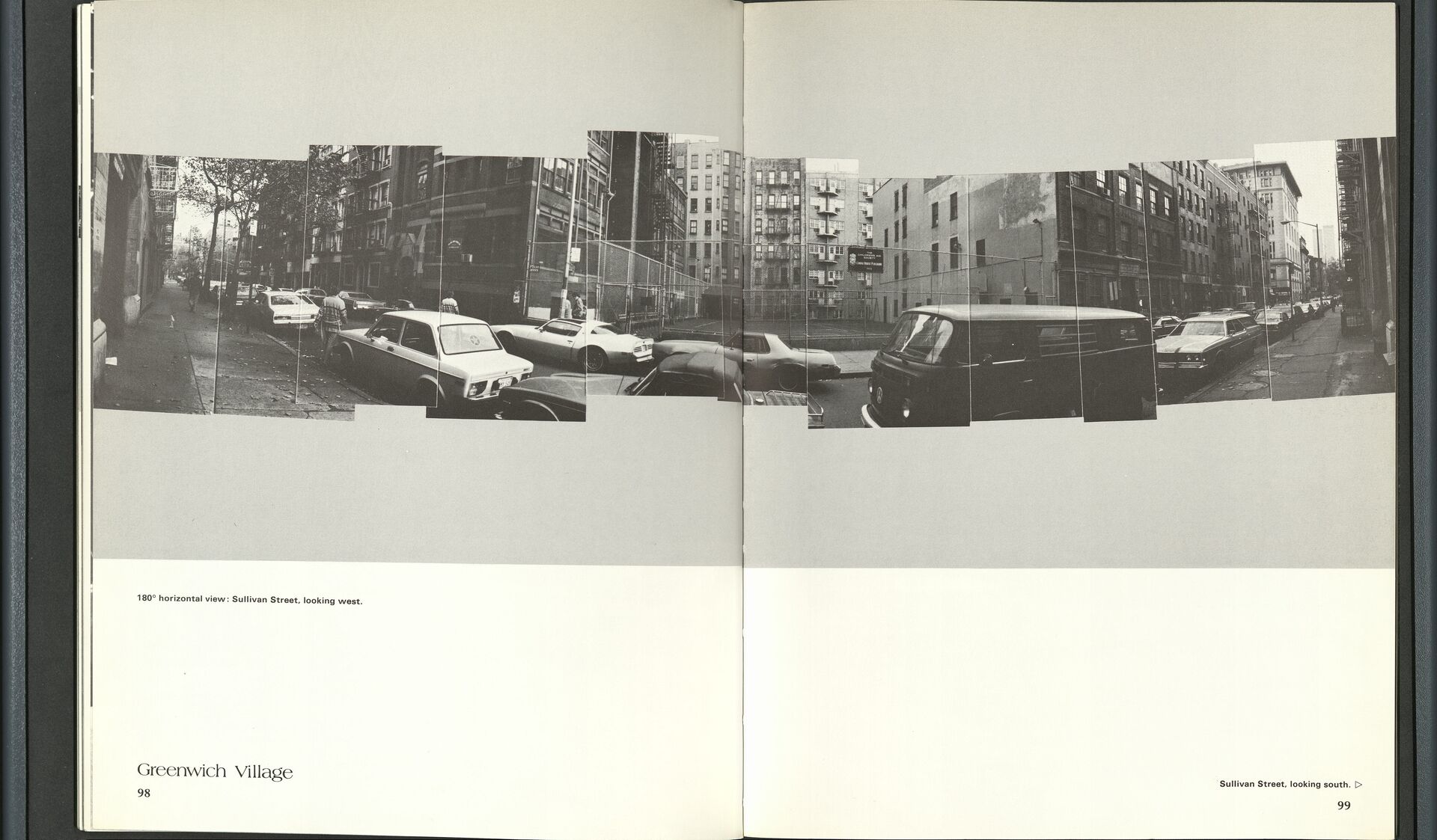

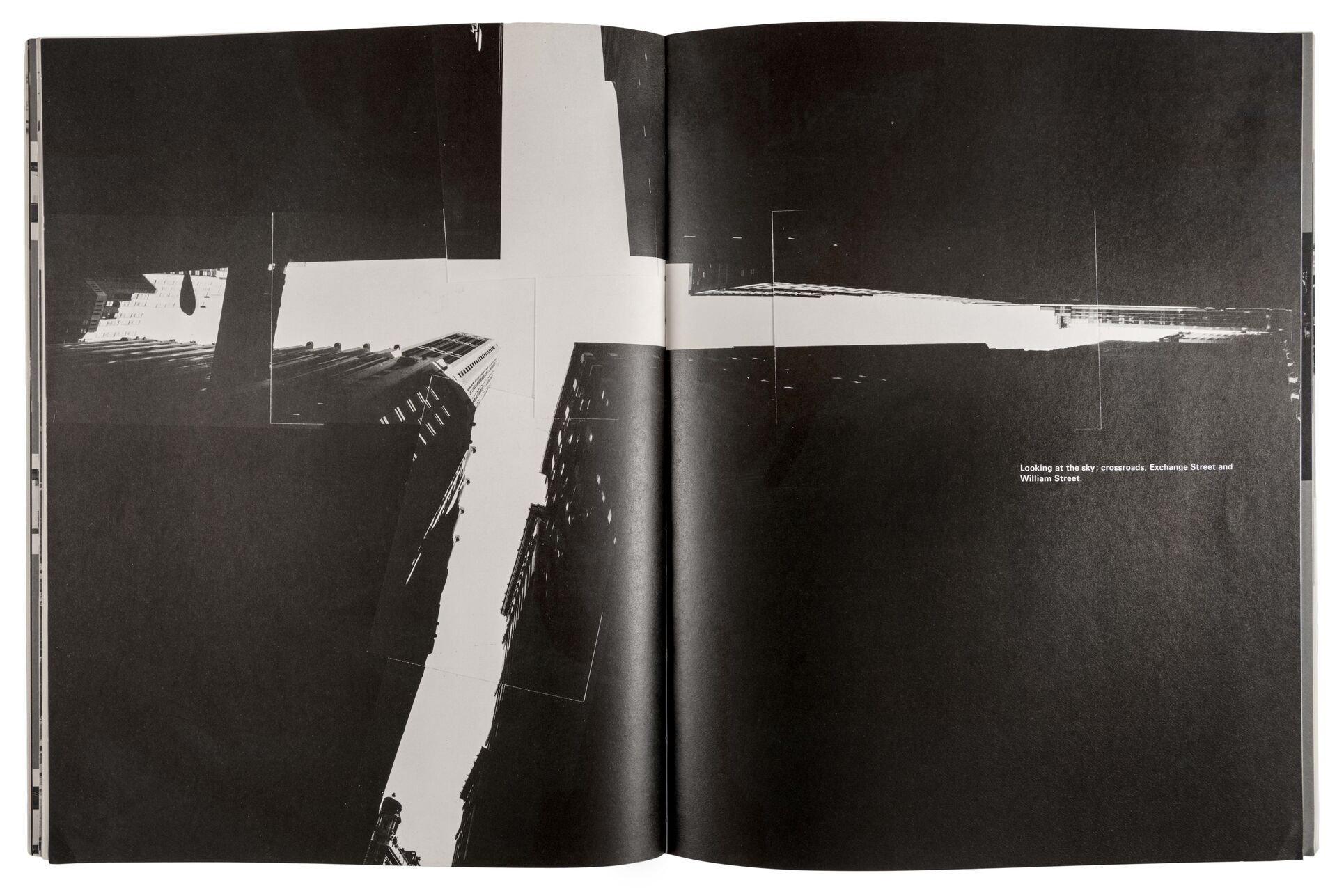

Another important element in Mestdagh’s study of the relationship between the material city and the human body begins with the observation that the body of a city dweller is always on the move. It’s not a stable, frozen body fixed in space but a mobile body walking and looking around. Making this aspect visible via photographic means is not as easy as it may seem. After all, a photograph is always taken from a fixed vantage point. No matter how the photographer holds the camera, each shot is made from a precise position and reflects only what can be seen from that exact point in space. Mestdagh’s solution was to swap the single view for a multitude of views stitched together in a panorama. She employs two types of panoramic images, one organized around a horizontal axis, the other around a vertical axis, and both exist in the form of semi-circle (180°) and full-circle (360°) panoramas. In either case, the stitched images suggest a mobile gaze, creating a kind of travelogue in which the viewer is invited to repeat the photographer’s gesture of gazing around.

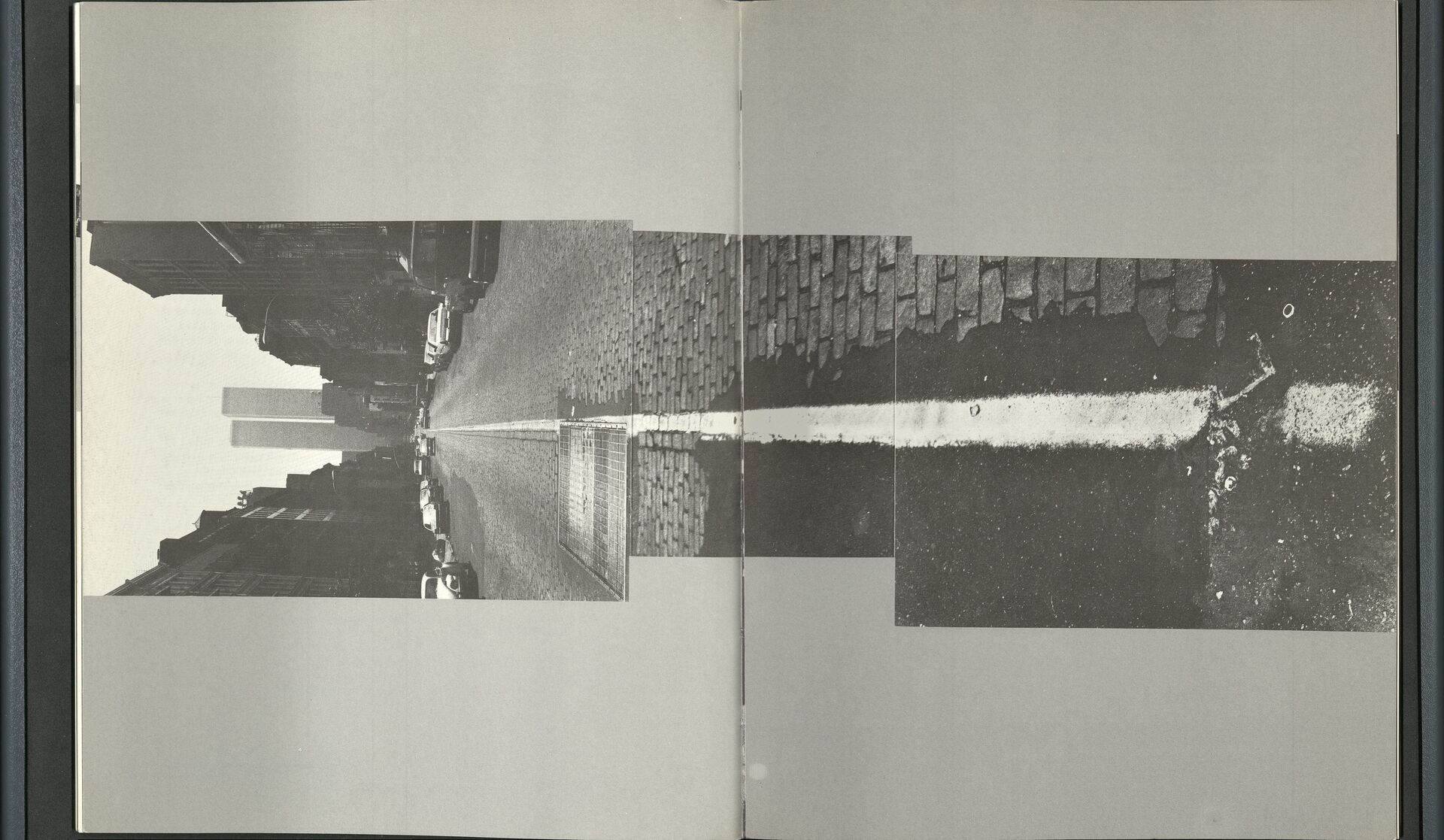

The vertical panoramas connect earth and sky. They start by looking straight downwards to the street before tilting incrementally upwards until the gaze is aimed at the sky, after which a reverse movement takes us back down to the ground. In these vertical panoramas, the sky is often just a small fragment between a dark mass of asphalt and concrete. In most vertical panoramas, the sky is a blank space; only in a few is it full of clouds, presenting the viewer with a vivid, ever-changing spectacle. Taken together, these panoramas, cloudless or not, suggest that there is no real breathing room in the city. In places where the streets are narrow, such as Wall Street, the sky is but a small line, a shimmer of unreachable brightness, piercing a dark mass of colossal skyscrapers. And even in the wider avenues, the sky is first and foremost an absolute vacuum, an empty void without any redeeming qualities. It’s as if the high-rises push it even farther away from the strollers on the street, as if the whole purpose of these towering buildings left and right is to incarcerate residents in concrete, steel and glass.

A similar feeling of seclusion is often present in the horizontal panoramas. Except at the extremities of the images, there are no holes, no broad vistas beyond the walls of buildings in front of the photographer. Made by pressing her body against one side of the street and then looking carefully from left to right, Mestdagh’s panoramic images present an all-encompassing overview of the street on which she stands. In so doing, they expand our spatial awareness: they show, in one sweeping move, more than we could humanly perceive. As such, they seem born from a desire to observe, an attempt to exert control over space. It’s like she used the camera to scan the streets with a vigilant eye, always on the lookout for potential danger, for an unexpected burst of violence. These horizontal panoramas relate to the sentiment of danger that seemed to prevail on the streets of New York at the time. Every person Mestdagh talked to acknowledged this sense of looming danger, and all had a more or less similar approach to addressing their feelings of vulnerability. To feel safe on the streets of New York, they suggested, required vigilance; you had to scan the streets for risky situations, all the while presenting an air of purpose and confidence, all the while walking tall and self-assured. None of the people she spoke to had been mugged or assaulted, and all claimed that was because they knew how to behave on the streets.

The book’s message is clear: this city of steel and concrete requires a character that is able to address it in kind; it requires someone strong, someone who won’t be messed with, someone as sharp and angular as the boxlike buildings that line its streets and avenues. This is the image Mestdagh presented the viewer of New York in the last years of the 1970s, not of a welcoming city but a stern teacher or treacherous mistress. As John, the TV director from Greenwich Village, put it: ‘This town is like a big woman, like a mistress. It is unbelievable, it is terrible. But it can be a real bitch, boy, if you’re depressed.’Roberte Mestdagh, Manhattan: People and Their Space, (London: Thames & Hudson, 1981), 94.