Lyrics from a Bob Marley song are referenced in red above one of the walls. ‘Emancipate yourself from mental slavery’, it reads. The entrance to the exhibition addressing Dutch colonial injustices in Amsterdam features two large LCD screens. A video plays on loop – people carrying flags as they walk barefoot along the dunes of the Dutch coast. Vibrant flags of former colonies are paraded against a stark background of yellow sand and blue ocean.

But where was my flag?

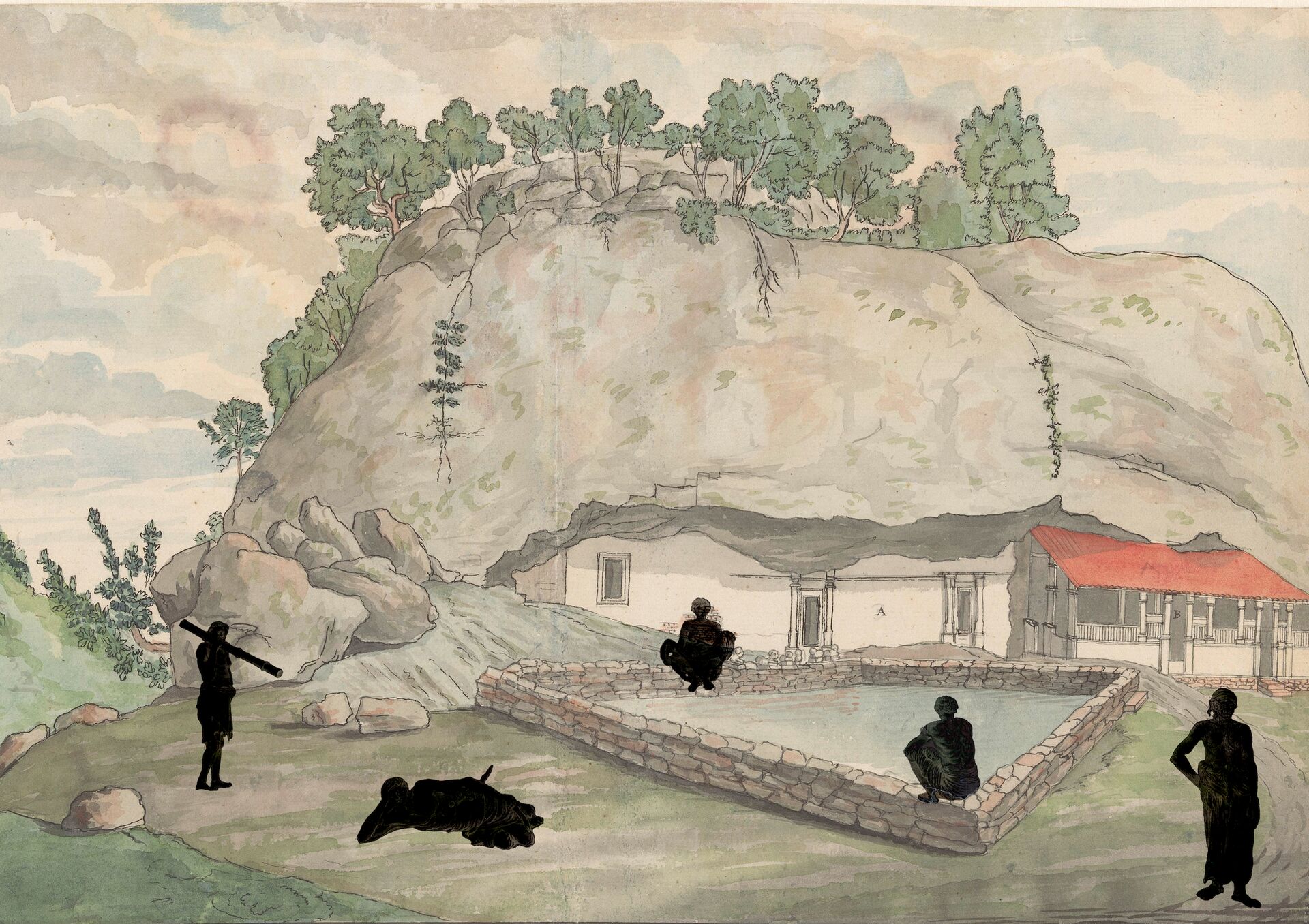

The Dutch VOC coat of arms for Ceylon as drawn in 1717 by an unknown artist for the report on the circuit tour of Governor I.A. Rumph.

My eyes dart across the sections of the elaborate museum installation, squinting at each of the descriptions, trying to find some mention of my home. Ghana, India, Suriname, Indonesia, . . . Sri Lanka.

There it was at last.

A footnote. One side of a glass panel dedicated to remembering over one hundred and fifty years of exploitation and settlement, using safe language to talk about colonial atrocities.

The exhibition is an ambitious attempt to acknowledge, inform, and educate the public about Dutch colonial history and its repercussions today. Visitors are supposed to be confronting colonial legacies, but it didn't feel like they were. All I could see was the encasing of objects of rich cultural and historical significance.

Glass cabinets with shiny spotlights illuminating their ‘subjects’. Prized possessions. Trophies. Stolen artefacts.

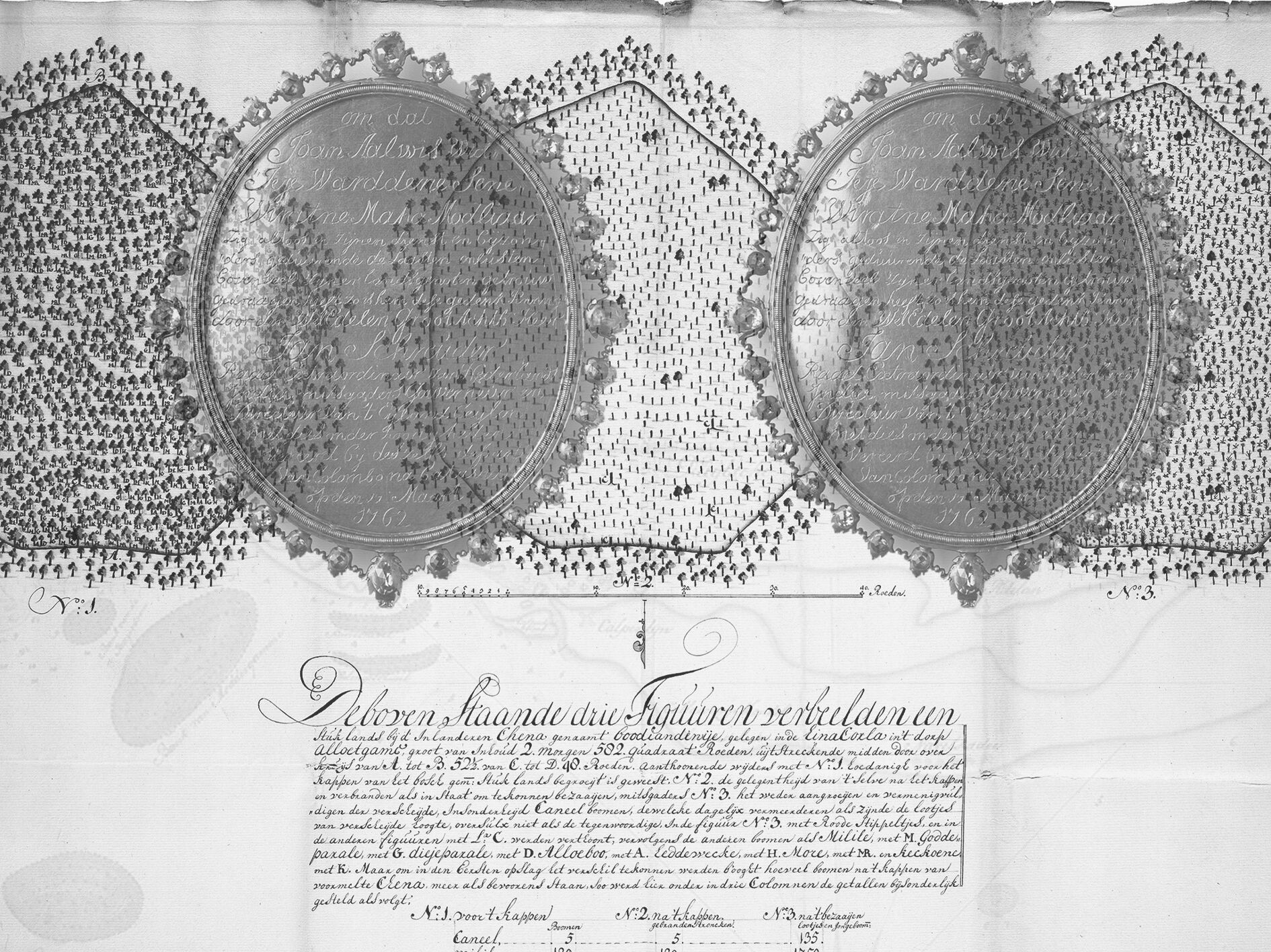

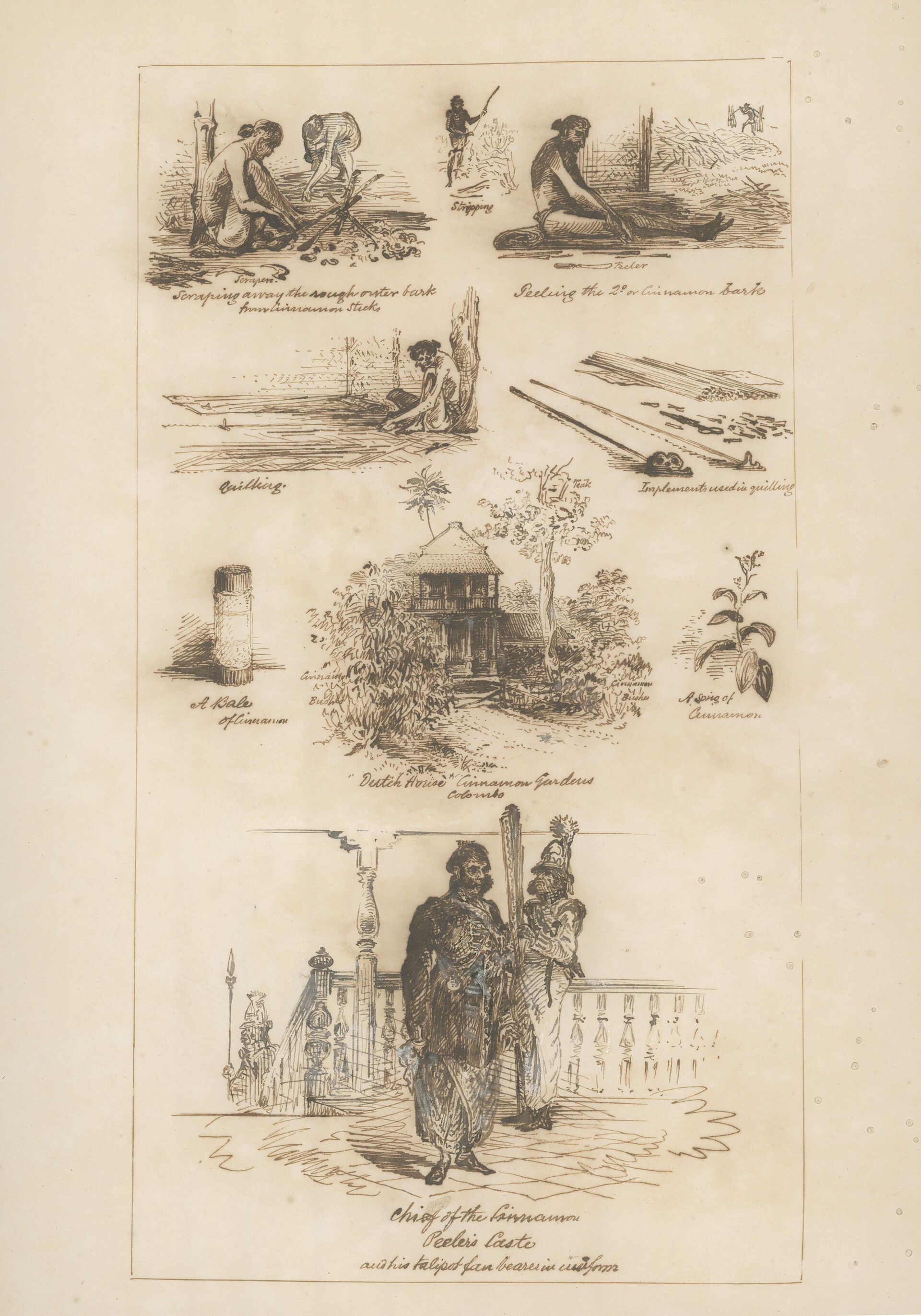

Process of cinnamon production from the book ‘Ceylonese Sketches’ by J.L.K. van Dort (1883).

Who is included in dialogues on decolonisation?

Which communities and ‘experts’ are consulted in the process?

Is an event like this an attempt to truly reconcile with the past, or an act of tokenism?

I feel small and insignificant among the tall columns and extravagant decor of the colonial-era building. As a non-Dutch visitor, I can’t help but reflect on just how entrenched these cultural institutions are in the very colonial systems they’re trying to shed light on.

Something that strikes me is the unbearable silence of these spaces. What grand narrative did these collections and installations bring forward?

What does honouring true provenance look like? Is it returning objects? Is it issuing an apology? Curating an exhibition?

How can we, as visitors, reflect better on these gestures and what they reveal?These reflections follow one of my first museum visits in 2022 to see the permanent exhibition Our Colonial Inheritance at the Wereldmuseum in Amsterdam, NL.

I was surprised by the noticeable absence of Dutch–Sri Lankan history within the exhibition. In the following months, I would come to find that this historical period was not addressed in mainstream dialogues about colonial history within the Netherlands at large.

These experiences formed the basis of my interest in understanding how colonial histories are told and maintained. They triggered questions about how to make space for alternative narratives and methods of storytelling – ones that are inclusive and representational and that go beyond traditional forms of display in order to interrogate histories.

Colonial nostalgia, fraught histories

The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) colonised Sri Lanka between 1658 and 1796. The VOC was the world’s first multinational corporation founded on exploiting networks of global trade and slavery. Yet, this significant period is absent from mainstream narratives on the colonial empire in the Netherlands.

Mural painting showing bales of cinnamon alongside a cinnamon tree in Balapitiya, Sri Lanka (2024).

As someone who grew up in Sri Lanka and recently moved to the Netherlands, I was struck by this apparent blind spot. Many Dutch people seemed unfamiliar with their country’s past colonial connection with Sri Lanka.

My hometown was a strategic base for Dutch imperialists. They built fortified walls, shipped slaves, constructed canals, and replaced wild forests with cinnamon plantations. Growing up in Colombo, Sri Lanka, I experienced a different relationship with Dutch–Sri Lankan colonial history, which had always seemed so naturally entangled with my own.I remember sitting on the ramparts of the Dutch fort in Galle, walking the cobblestone streets of the narrow fort while eating ice cream and soaking in the colonial-era villas and restaurants steeped in chic interiors. There was a sense of nostalgia in the air. These were relics, museums, and monuments that beamed a proud history and recognition of a foreign heritage inherited and amalgamated over the years. Even today, there are many visible traces of this colonial heritageUNESCO declared the Dutch fort in Galle, Sri Lanka, as a World Heritage Site in 1988. Since then, the fortified town of Galle has become a major tourist attraction and the largest colonial monument on the island. Following the end of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict in 2009, the Dutch government has been restoring many forts and complexes, creating attractive tourist hot spots and heritage sites. in architecture, food, culture, and language.The Dutch Burghers, descendants of Dutch VOC in Sri Lanka, are one example of living heritage on the island. The Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon, founded in 1908, is an active organisation in Colombo with a vision to ‘promote the moral, intellectual, and social well-being of the Dutch descendants in Ceylon’. The organisation is also well known for its ‘VOC cafe’, a popular restaurant serving Sri Lankan–Dutch Burgher foods.

Nira Wickramasinghe, professor of Modern South Asian Studies at Leiden University, remarks that in the last decades, Sri Lanka has produced its past through processes of ‘heritagising’, noting that ‘urban planners and independent designers began what can almost be described as a love affair with very specific aspects of the Dutch heritage’.Nira Wickramasinghe, from a speech delivered at the Rijksmuseum in 2016 based on her foreword to the book Cinnamon and Elephants: Sri Lanka and the Netherlands from 1600 by Lodewijk Wagenaar (Vantilt Publishers, 2016). Wickramasinghe refers to this as a ‘canny reversal of situations’, where ‘the colonial became the object of gaze and exploitation by market forces. While Portuguese and British colonialism are fading away, the Dutch past pops up revived, in multiple incarnations'.Wickramasinghe, 13. But I want to raise another question about how colonial pasts and contemporary consumptions ‘meet’: How does the bark of a tree growing in forests of a distant land find its way to your kitchen cabinet?

When the Dutch arrived on the shores of Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) in the early seventeenth century, they had one motive: to secure a monopoly on the trade of Ceylon cinnamon, harvested from the bark of an Indigenous plant. Cinnamon is a spice of stories that tell us about competing empires, bloody battles, forced labour, land appropriation, and resilience.

In the Netherlands (and most of the Global North), cinnamon has been reduced to a distinct taste that tells a story of cold winter days with mulled wine and spiced apple cake. This is paired with traditions and flavours that seem to be associated with holiday festivities. In Western recipes and cookbooks, cinnamon appears to have been wiped clean of its brutal past. Despite its popularity, most people are unaware of the fraught colonial history of this once highly sought-after spice.

I use the historical importance of cinnamon as a point of departure in my research to generate a critical dialogue that unpacks some of the forgotten stories and violent histories from this period. Through the process of unarchiving and unframing archival material, I hope to reclaim its meaning and offer new ways of engaging with this complex and nuanced history.

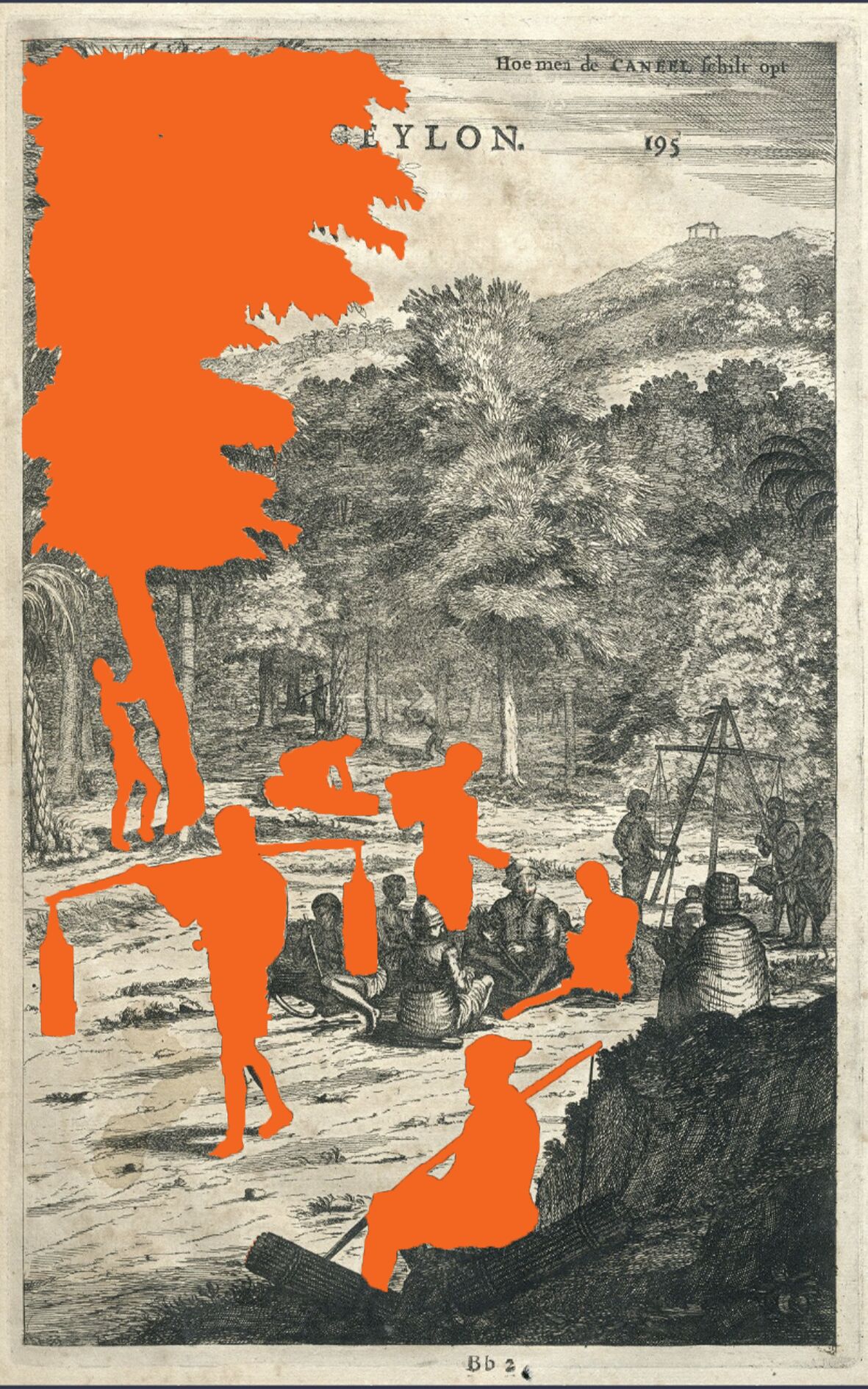

Archival intervention of ‘Cinnamon Peelers’, anonymous (c.1672).

Unarchiving through photography

Photography had not yet been invented in the seventeenth century. Paintings, drawings, and maps fuelled the Dutch colonial gaze on a distant paradise, a place of abundance that was available for exploration and exploitation. Images from this period depict colonial classics: idyllic and expansive scenes of rolling hills, depopulated landscapes, and its people as ‘natives’ in an antique land.

The western colonial gaze portrayed the cinnamon tree using botanical drawings throughout most of history. Drawings from the seventeenth and eighteenth century offer a scientific look at the leaves, flowers, and buds of the cinnamon tree.See, for example, the drawing of Cinnamomum verum (Ceylon cinnamon) from Köehler’s Medicinal-Plants (1887).

Today most people only relate to cinnamon as a packaged product. Through my practice I offer another way of ‘seeing’ the tree, by playing with the idea of cinnamon as the protagonist in my story – one that has witnessed momentous changes over the years yet remains unchanged within the landscape. Using a studio-like setting with bright colours to photograph parts of the tree, I hope to flip the conventional gaze of how it has been traditionally documented.

Considering the affordances offered by the archive as a bridge from the past to the present, I unarchive material from this period and build on it through visual interventions such as collages. By layering the past and present, I’m blending these elements to create a composite image that juxtaposes the tensions and violence embedded within contemporary landscapes and archives. Cutting, manipulating, and editing images in this way allows me to recreate their meaning – to introduce a personal narrative and to question the archive and its role in shaping history.

The collages offer a democratic process in accessing archives, making it possible to shift the context of these colonial narratives from the political to the personal. They serve as a tool for cultural commentary, enabling me to address what is erased in archival material and to suggest potential ways of decolonising our gaze.

Apart from the archival interventions, I explore the role of oral history in re-contextualising colonial legacies. Oral traditions in the form of poems, songs and folk tales were an important form of knowledge production in Sri Lanka. By developing a short video essay that includes personal vignettes of my journey during my research process, I hope to unpack the ways in which oral storytelling may contribute to the notion of unarchiving and bridging the past and present through visual media.

Reframing histories

I’m intrigued by the different ways in which Dutch–Sri Lankan colonial history is encountered – the history is absent from mainstream narratives on the Dutch colonial empire, while in Sri Lanka this period is associated with a type of colonial nostalgia.

My ongoing research examines the ways in which visual media can be used as a field of knowledge within artistic discourse to address colonial legacies and the wider context of historical, social, and cultural relationships between the Netherlands and Sri Lanka. I reflect on questions that must be addressed today to ensure that we acknowledge and confront our history in a way that allows us to create a future that doesn’t look like our colonial past.

My process of working with seventeenth and eighteenth century pre-photographic images and my own photographs create an opportunity to bring visuals from different eras together to unarchive historical material through the medium of photography.

While certain elements of our past have been erased or forgotten, I propose other ways of looking at a shared history that has been overlooked and underrepresented. I hope to encourage audiences viewing the final work to question imperial legacies, disrupt power structures embedded in archives, and explore the radical possibilities of alternative narratives.

Editor's note. This contribution is part of our 'Unframing' series. Read the introduction by guest-editor Nuria Bofarull here.