From its inception, photography has been considered a natural ally of the sciences. It’s been a technology for observation and discovery as well as a tool of documentation and authentication. Historically, it was widely employed across the field of scientific activity, spawning numerous archives and repositories. Revisiting such archives has long offered artists a way of interrogating scientific histories and unsettling established institutional narratives. Mike Mendel and Larry Sultan’s project Evidence, a collection of photographs from hundreds of state and private technical, forensic, medical and scientific archives, is a frequently referenced example, often quoted as an ‘undisputed classic’. Its 59 photographs challenged normative ideas of science as detached and disinterested, revealing instead a space of embodied and eccentric experimentation.In this article, I refer to the original edition of Evidence, printed in 1977. In 2004, an expanded version of the book was published by DAP/ Distributed Art Publishers, which included a facsimile copy of the original material. In 2017, the 2004 edition was released as a hardback book, also by DAP. The title of the work was a comment on the enduring compact between photography and science and their shared disciplinary attachment to ideals of objectivity and truth. Under Mendel and Sultan’s supervision, scientific practices were exposed as distinctly social and performative in character.

Yet, Evidence also provided proof of another kind, as if more were needed, that scientific knowledge is embedded in broader social inequalities and built on the experiences of predominantly White men.This article, written in March 2020, concentrates on gendered rather than racialised representations. I wrote this as a white woman, aware of the intersectionalities between gender, race and other forms of oppression, and of the widespread structural and institutional racism within the sciences. In that respect I feel the omission of this in the article makes me complicit in reproducing racist silences. The sciences have enabled and legitimised racism, proposing race itself as a scientific category (biology, medicine, ethnography to name but a few disciplines), a concept that has and continues to be used to justify racialised violence. I am educating myself further and reading on race and science, starting with Angela Saini’s book Superior and working my way through references on Chanda Prescod-Weinstein’s reading list on decolonising science. Women, on the few occasions they appear in the photos, are in supporting or assistant roles: holding, watching, childminding. They also make disembodied appearances, an arm holding an object in the frame while the men are represented doing the important jobs of testing, learning, recording and measuring. The history of science is full of such images, and reproducing archives risks participating further in such inequalities, colluding with practices that privileged some voices and devalued others.

So how might interventions in scientific archives open broader ethical questions about the production and reproduction of knowledge? In this essay, I consider the work of three female artists – Regine Petersen, Sophy Rickett and Kate Morrell – who interrogate established scientific histories through archival practices.As far as I’m aware, the key texts on archival practices by writers such as Benjamin Buchloh, Jacques Derrida, Okwui Enwezor and Hal Foster have not considered questions of race or gender within archives, nor paid specific attention to scientific archives. They visibilise authorship, observation and subjectivity, which are aesthetic strategies traditionally silenced or suppressed in scientific representation. Playing with the relationships between image and knowledge and past events and their documentation, the artists reframe and reimagine photographic evidence. They embrace ambivalence, uncertainty and partiality, resisting the singular authority of the archive to suggest a more unstable scientific ground.

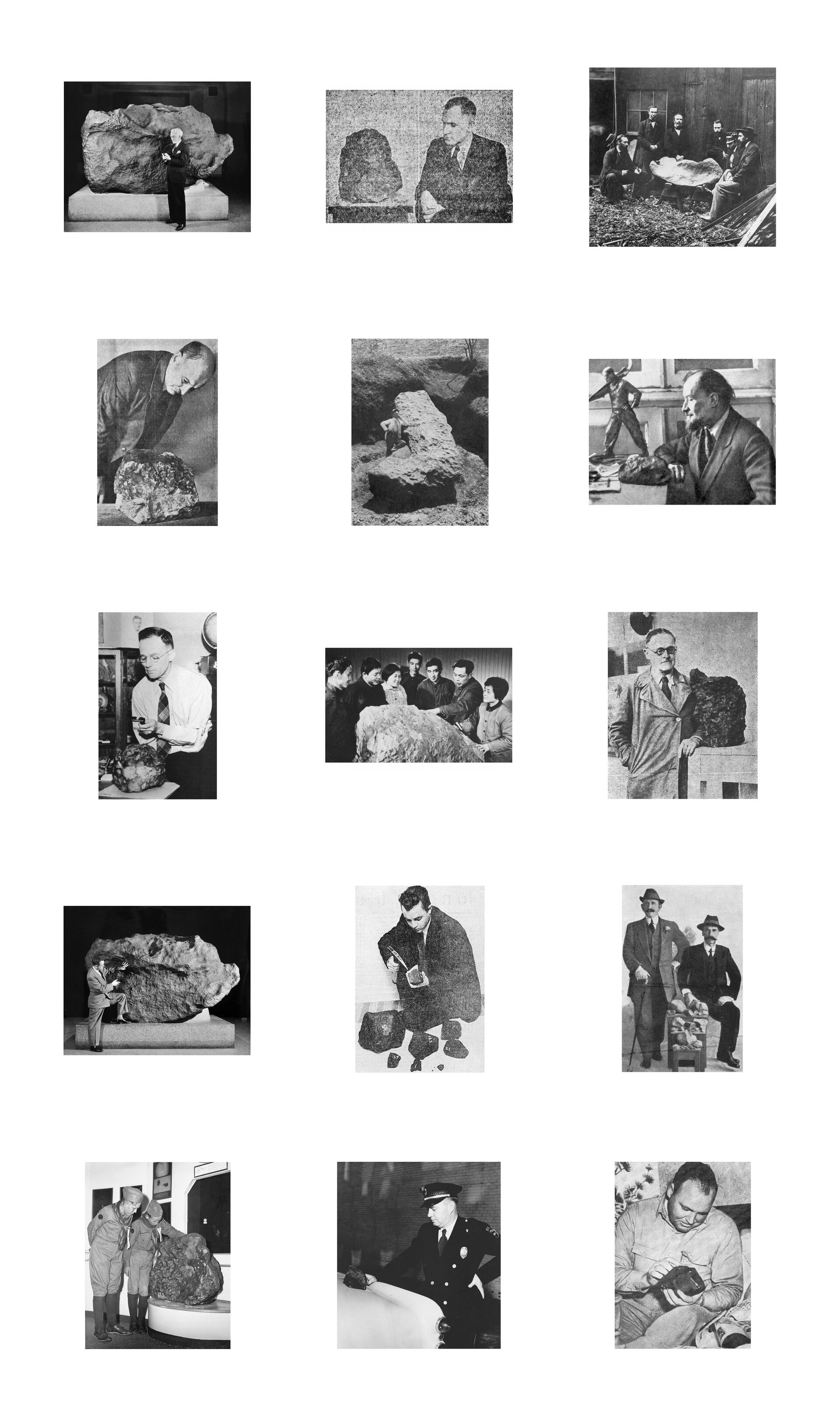

Regine Petersen, Screenshot from Men with Meteorites, 2012 - ongoing.

I’m not arguing here for a female way of seeing, and especially not a female counter-scientific way of seeing, but I am interested in how a focus on gender might disturb certain assumptions embedded in both photography and science. Feminist inquiry can expose categories of thought embedded in scientific and photographic discourses around familiar binaries, such as subject/object, original/copy, subjective/objective and art/science.For more on these extensive and complex philosophical ideas and histories, see, for example, the writings of Donna Haraway, Katherine Hayles and Isabel Stengers. In situating knowledge and connecting it to subjectivity, a gendered inquiry can help break down these oppositions and politicise assumptions about whose knowledge, expertise and authority resides in archival material.

Petersen’s Men with Meteorites, a collection of archival and press photographs acquired by the artist over years of research, emphasises that which Evidence ignores: the gender of its photographic subjects. Male individuals – recognisable as scientists, labourers, collectors, farmers, soldiers and policemen – were photographed with rocks at meteorite-impact sites and in museums, briefing rooms and anonymous institutional spaces. The material is unlabelled and uncredited, dislodging it from its documentary origins to create an ethnography of the figure of the male scientific observer. Published on Petersen’s website as a grid of 39 photographs, Men with Meteorites plays with taxonomic convention, using the syntax of the image to propose a new categorical type. The collection works as a refusal to normalise men as natural scientific subjects. It’s also a comment on the visual culture of scientific knowledge; it says that photographs of meteorites need to be witnessed by the men in the image if they are to function as evidence.

In selecting photographs in which the subjects are absorbed by the meteorite and inattentive to the camera, Petersen made a broader comment on representation. She isn’t interested in these men as individuals but as symbols of a particular era of science photography in which objects were props for performing knowledge. In her work, the personal gives way to the phenomenological, and the collective gesture of the gaze acts as a metaphor for the relationship between vision, men, nature, possession and desire. The meteorites function like trophies, helping to assert the separation and superiority of men over the natural world. But there are contradictions and ambiguities here too. The meteorite as a photographic spectacle seems to fall short, its power as an object of cosmic fascination seemingly beyond representation. Instead, since nothing in the photographs is concealed: the small human dramas prevail, the repressed sentiments of pride, possessiveness, ambition and bemusement just legible in the faces of the subjects. And perhaps there’s something here that Petersen identifies with. After all, she’s a collector herself and is part of the story she’s telling.

Petersen co-opted classificatory methods to show us how very subjective it all is, how vulnerable photographs are to re-categorisation, how precarious the relationship between images and knowledge. Men with Meteorites is part of a much larger body of work, one of many chapters in an extensive and visually complex project, and it’s this context that shapes our interpretation of her work. By absorbing these images into this personal project and establishing them as an archive, she’s invited us to think about the way that historical accounts are always shaped and validated by the people who tell them.

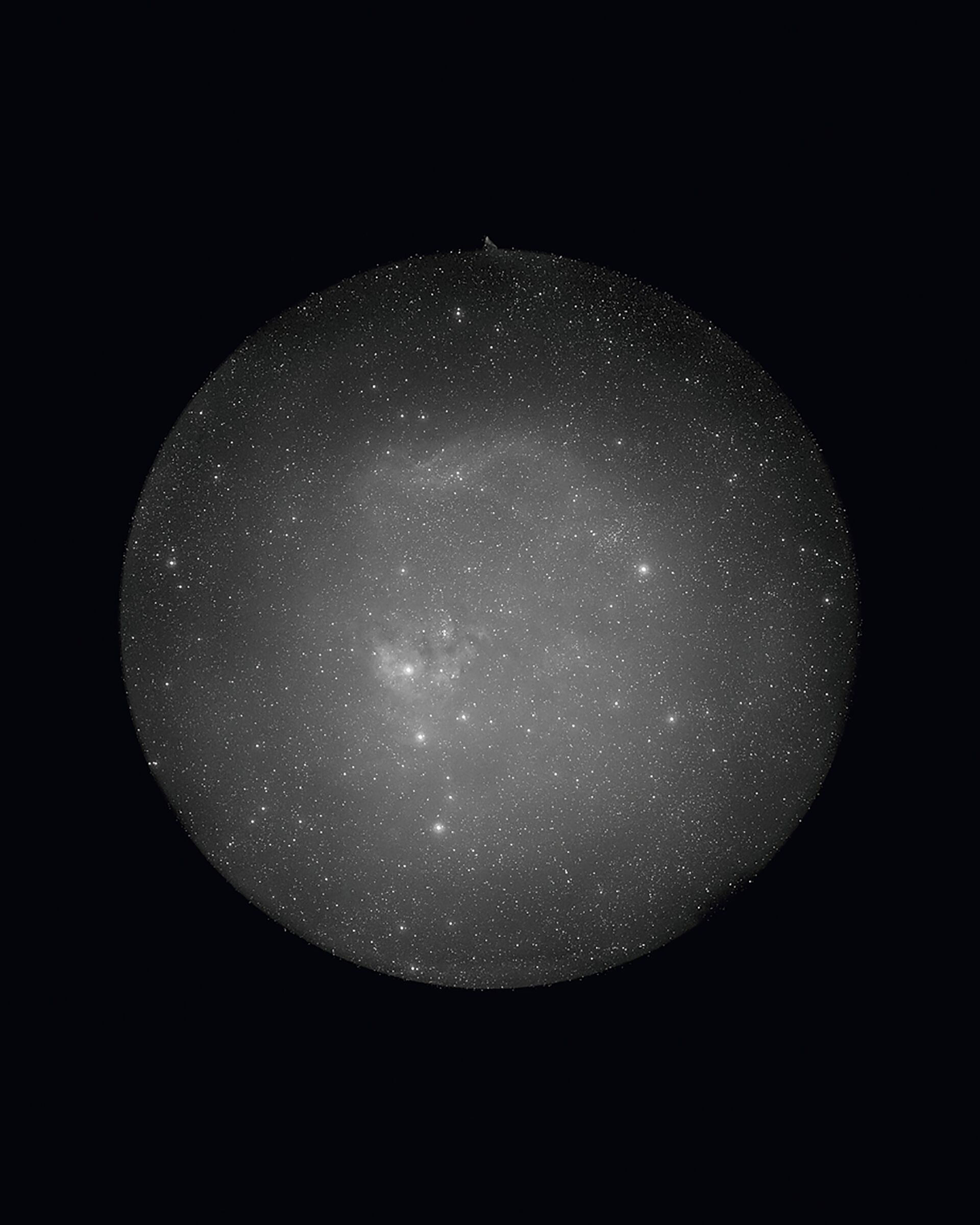

Sophy Rickett, Installation of works from Objects in the Field: Observation 111, Breese Little, London, June 2015, Courtesy of the artist.

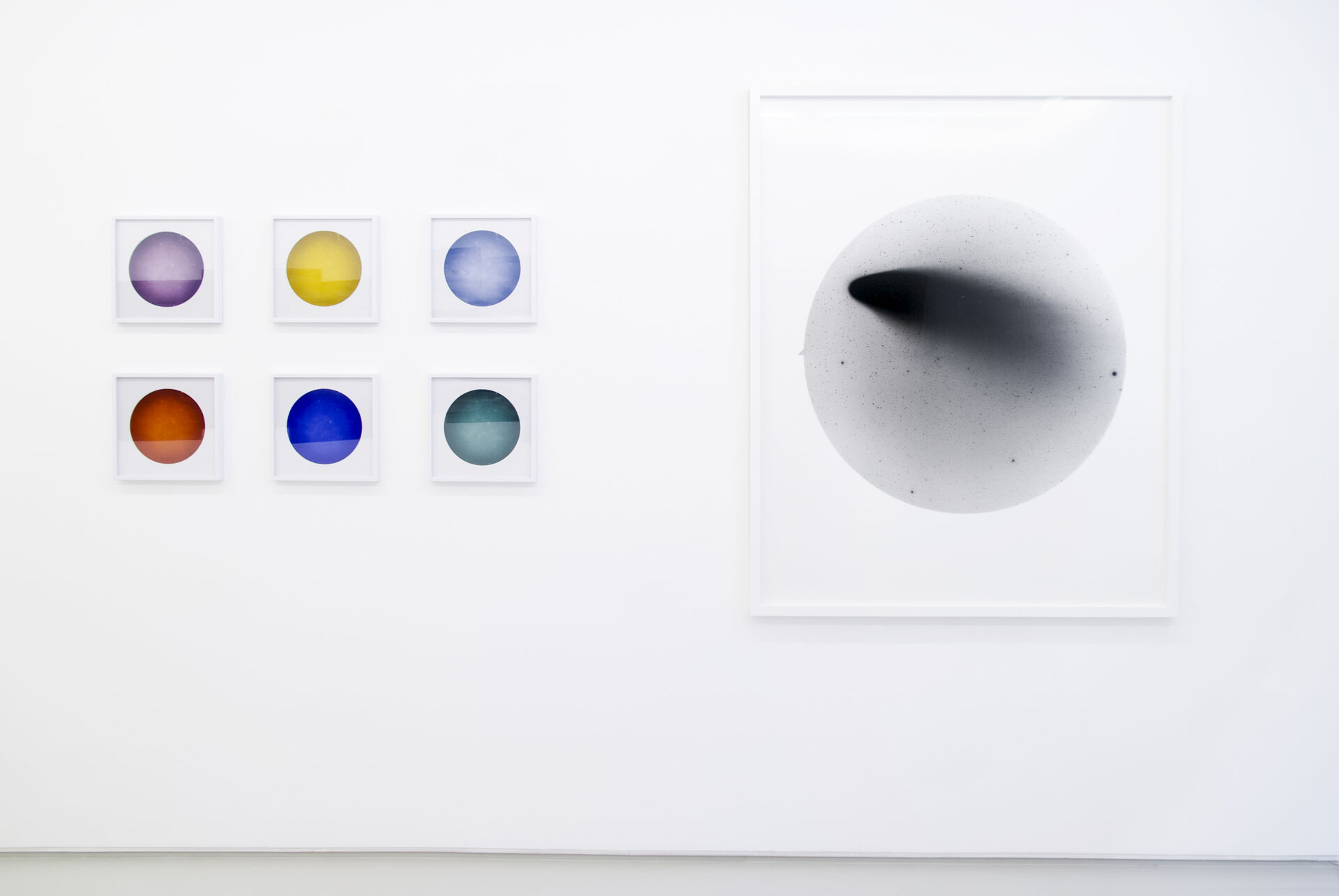

Sophy Rickett, Installation of works from Objects in the Field: from left Observation 95 (10 parts) + Observation 123, Breese Little, London, June 2015, courtesy of Breese Little.

Rickett, in her project Objects in the Field (2014), asks Dr Roderick Willstrop, a retired physicist from the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge, ‘If I print the negatives, will the photographs be of scientific interest?’Personal communication with the artist. Email from Sophy Rickett, 11/04/20. She’s referring to his archive of photographic negatives from the 1980s made with The Three Mirror Telescope, an imaging device that he designed and built. The answer comes back quickly: ‘No.’ The negatives were too old, and things had changed too much for them to be of scientific value. But Rickett printed them anyway, and this tension between the negative and its material possibilities runs through the project.

Where Rickett had hoped to find alignment with Willstrop through their shared interests in the night, photography, optics and the sky, she experienced resistance. She was interested in the images as personal and cultural objects: the fingerprints on the negatives and the residues left from drying, the traces of the scientist’s presence and process. But for Willstrop, the negatives remained resolutely obsolete, a set of scientific measurements of limited contemporary value. As Rickett explains in her work, ‘the material in the middle stays the same, but it’s contested, fought over.’

A text by Rickett, distant and melancholic, offers a fragmented account of her encounters with Willstrop and is mediated through memories that resurfaced during the project. In it, she recalls having her eyes tested as a child, reminding us – and perhaps Willstrop too – that what we see is connected to our histories and experiences, implicitly challenging the idea of technology as neutral, and bringing vision back to the body. Rickett mediates between hope and disappointment, a tension between a desire for engagement and artistic autonomy.

In printing the negatives, Rickett reimagined them, privileging scale, surface and colour, and subverting their status from scientific document to artefact. In this retrieval – or rescue – of the archive, her project inhabits a borderland between appropriation and collaboration. There’s a sense of artistic responsibility, perhaps less to the science and more to Willstrop himself, and the project has many gestures of his authorship and participation. For example, she co-opts his objects in the field for her title. In her orbit, this scientific grammar becomes poetic and open: the objects might be the stars or the photographs themselves, and the field might be the sky, the gallery or another institution. Willstrop’s story becomes hers, the scientific embedded in the personal. And this is what fascinated her: ‘On its own the material doesn’t mean anything. It needs de-coding and interpreting and as soon as that happens, it stops being neutral. The material is hijacked by the context, and subject is assigned, it’s not already there.’Personal communication with the artist. Email from Sophy Rickett, 11/04/20. I was left wondering if the subject here isn’t Rickett herself.

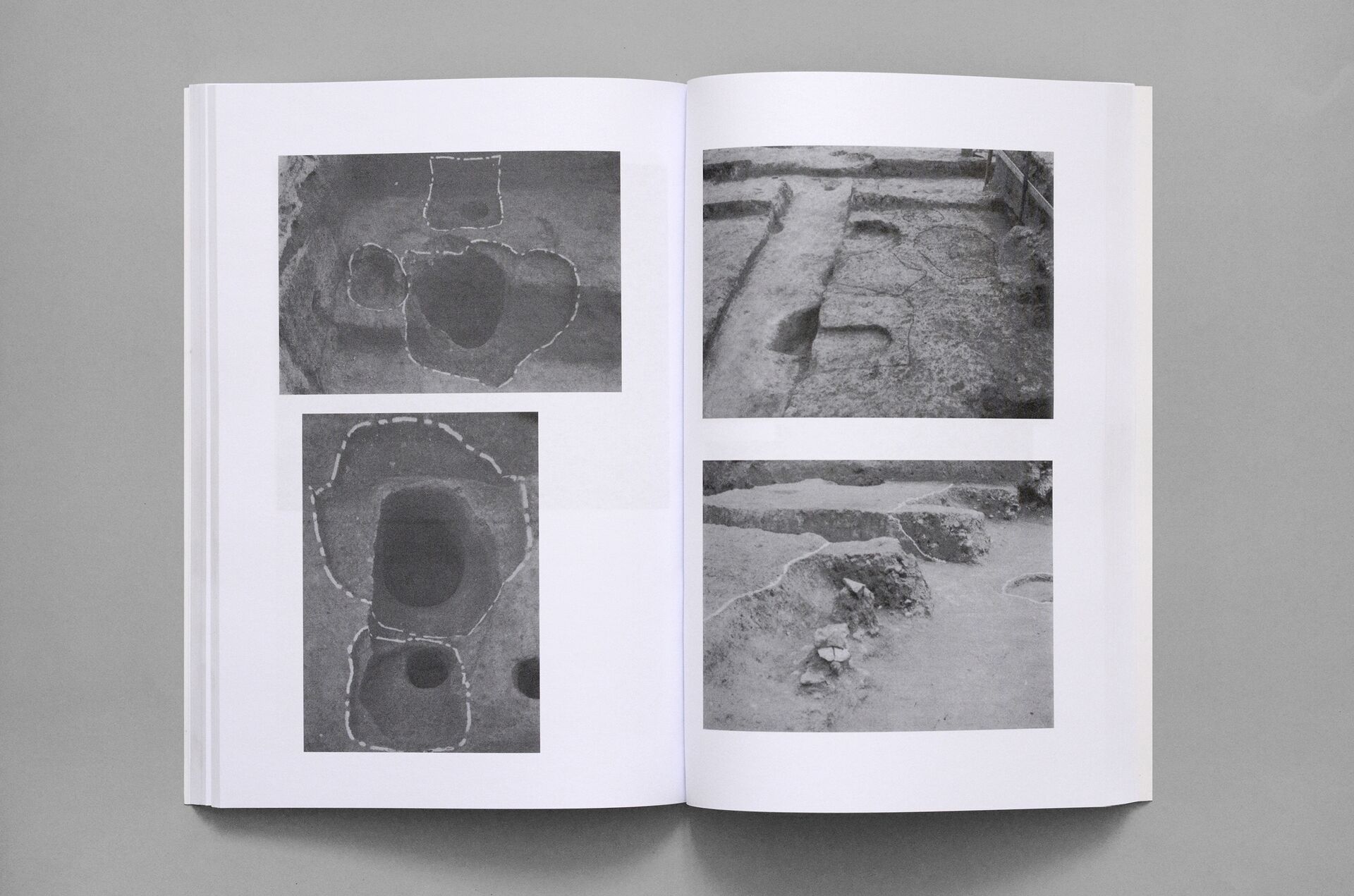

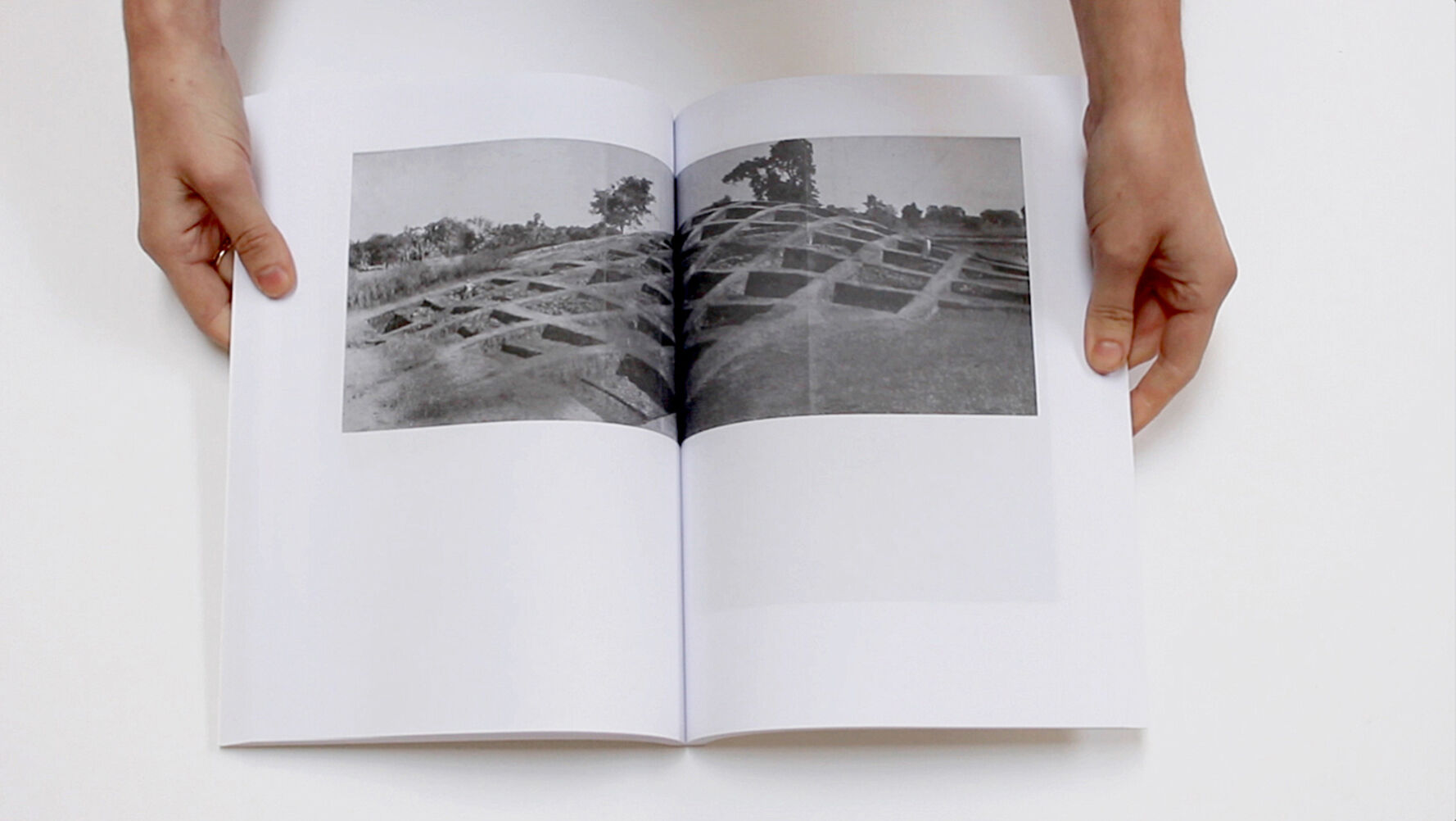

Kate Morrell, Hoard: The Ethics of Acquisition, 2012.

Kate Morrell, Hoard: The Ethics of Acquisition, 2012.

Morrell’s book Hoard, The Ethics of Acquisition engages with documentary images and practices of classification. In a unique artist book, she reprinted hundreds of photographs of international archaeological sites originally encountered in a report and subsequently sourced and scanned from books in the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies’ library. In her reproductions of the photographs, Morrell suppressed all the original scientific information. She excluded important source text as well as photographs containing annotation, artefacts and people, a process of clearing that mirrored the archaeological preparation of the ground and resulted in a catalogue of empty sites. These read like inverse monuments, negative spaces left after archaeological finds are removed.

By adopting archival measures – digging around in libraries, unearthing and ordering photographs – Morrell exposes archaeological and colonial practices to new forms of inquiry. In this ethical excavation, the library becomes the looted site. This decontextualisation works as a further metaphor for the removal of archaeological ‘finds’ and their display as artefacts in museums and institutions. Stripped of scientific value and authority, the 700 photographs – presented originally as a book and subsequently made available as a print-on-demand publication – interrogate archaeology’s material and ideological practices. The publication, which is densely configured with images, plays on the idea of the ruin and uses the image of archaeological aftermath as a visual motif, raising the possibility of a disciplinary violence.

As an archaeological term, ‘hoard’ describes a collection of valuable objects or artefacts. But it also refers to the social condition of compulsive accumulation and storage of objects. In this title, Morrell foregrounds her own desires and interests while also alluding to the ethics and colonial histories of excavation, acquisition, ownership, access and display.

‘Archival practices have the potential to radically reframe marginalised voices both past and present,’ Morrell explained. ‘Working between objects, anecdotes and written documents, my work challenges conventional relationships to such sites, which can be patriarchal and exclusive. I am interested in these gendered readings of landscape.’Personal communication with Kate Morrell by email, 16/04/20. The concept of reinterpreting archaeological and historical material is one that recurs across Morrell’s work. In Index. A Land, she reanimates the index of a book by Jacquetta Hawkes, an important but overlooked archaeologist and nature writer; and more recently, in her moving image work Y El Barro Se Hizo Eterno, she foregrounds the collection practices and narratives of non-European women, opening spaces for more subjective and emotional ties to archaeological objects and events.

A feminist interpretation implicitly challenges the premise of the world as an objectively knowable reality. Observation is reconfigured as subjective and mediated, opening a space between science and photography that is porous and contingent. Photographs are pulled from established disciplinary frameworks and networks of authority and regenerated through acts of authorship. By co-opting and reimagining scientific methods, such as speculation and classification, these artists re-expose archival photographs. This gesture of re-exposure – reprinting, republishing, reproducing and recontextualising – destabilises the relationship between photographs and evidence and between disciplinary boundaries, producing new flows and dialogues.As such, these works also feel distinct from the mainstream public discourse about ‘arts and science’, with its language of synergy and emphasis on win-win. In that model, arts and science seem to remain hierarchically distinct but are able to harmoniously combine to produce an enhanced whole.

There’s an ethical friction in these representations, especially in the work of Rickett, that arises from considerations of consent and authorship. But of course, this is the point. These new interpretations are no more truthful or valid than their archival counterparts. The artists do not seek to correct or to erase histories but, rather to reveal something of their ideological origins, undermining any exclusive claims to a fixed or singular photographic truth. In so doing they disrupt the representational compact between photography and science, institutions and archives, images and histories, allowing instead for ambivalences and uncertainties.