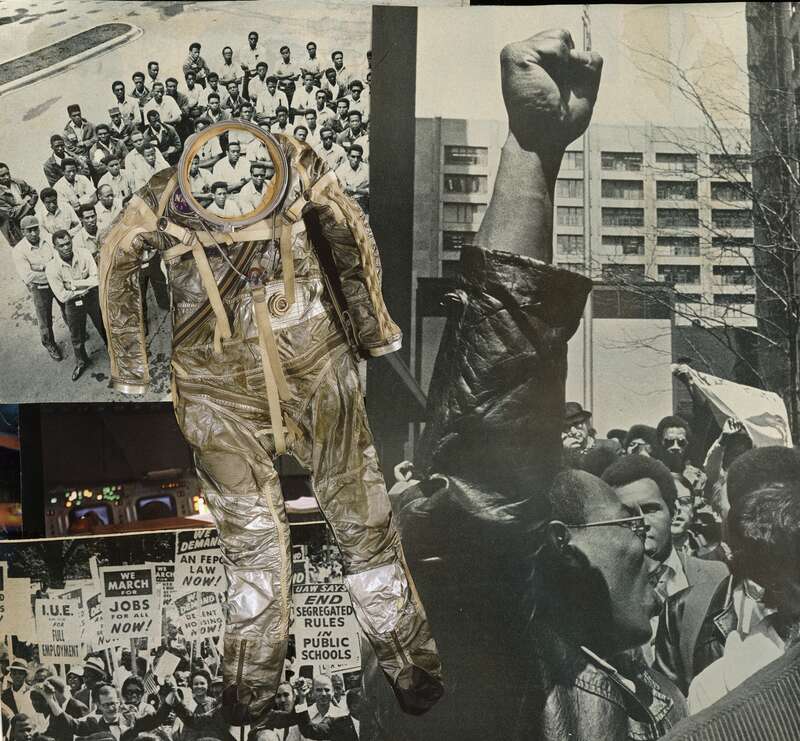

Film still. Black Space Agency Training, Black Quantum Futurism, 2019

Radical Futurism: Documentary's Chronopolitics

This essay is the result of a collaboration between Trigger and Revista Zum.

T. J. Demos

11 jun. 2021 • 14 min

With her compelling contribution to Indigenous futurism, Thirza Jean Cuthand’s Reclamation, 2018, documents what’s to come. Premised upon a mass settler exodus to Mars, the short video portrays a broken, abandoned Earth left to Indigenous peoples who, freed of extractive devastation, toxic racism, repressive heteronormativity, and the endless wars and violence of capitalist property relations, subsequently begin the work of post-colonial environmental restoration. Delivered through familiar documentary tropes, the piece showcases interviewees discussing their newfound lives, with contextualising footage of dystopian landscapes presented in the evidentiary mode, with a handheld camera’s reality effects. Its futurism unleashes radical formal possibilities in both decolonizing time—reversing conventional documentary’s ties to pastness, projecting the that-which-has-been into the what’s-to-come—and generating forces of creation beyond the mimetic doubling of reified and colonial realities. It thereby lays an explosive charge in the present through performative imagination, rendering the future-as-disruption that much more probable.

Here, documentary figures as the creative practice of chronopolitics, designating the politics of time as much as the time of politics, both implying there’s nothing natural or inevitable about how we organise temporality. As such, documentary provides a technology for revealing portals into futures alternative to the now –recalling Arundhati Roy’s description of the current pandemic conjuncture: structural breakdown discloses newfound opportunities for a creative transformation of what’s yet to be.Arundhati Roy, ‘The pandemic is a portal’, Financial Times (London, England), 3 April 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca. Passing through that portal, we can cast a barrier of eternity between the barbarism of the present and the justice of the hereafter.

Still image (dumpster scene) from Reclamation by Thirza Cuthand, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

Still image (walking hand in hand scene) from Reclamation by Thirza Cuthand, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

The stakes are indeed enormous. We’re caught in a situation in which time has been colonised, racialised and economised, generating what Black Quantum Futurism (BQF), the Afrofuturist collective based in Philadelphia, term the ‘temporal ghettos’ of racial capitalism, where the ‘Master(’s) Clock[work Universe]’ unevenly distributes spatiotemporal mobility, agency and determination.Rasheedah Phillips, ‘Dismantling the Master(’s) Clock[work Universe], Pt. 1’, in Black Quantum Futurism: Space-Time Collapse I: From the Congo to the Carolinas (Philadelphia: AfroFuturist Affair, 2016), 25. Just as material inequality reigns, we also succumb to the endless present of capital’s calculative machinery, seemingly rendering resistance pointless. Time operationalised as such recalls what Jasbir Puar terms ‘prehensive futurity’, a chronology that ‘inevitablizes’ a desired unfolding: ‘we cannot get out of the present because we are tethered to the desired future; past, present, and future feel somewhat futile as descriptions of temporal distinctions.’Jasbir K. Puar, ‘“Will Not Let Die”: Debilitation and Inhuman Biopolitics in Palestine’, in The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 148. Conventional documentary tends to reify that time trap.

Cuthand’s Reclamation – a decolonisation of time as much as of space – poignantly contests dominant approaches to time, including technolibertarianism’s prehensive futurity and its colonialism of land, the economy and the infosphere of communications as much as of temporality. It’s as if its vision of what’s-to-come is a foregone conclusion, as when billionaire tech-entrepreneur Elon Musk, who, in response to charges of complicity in the recent antidemocratic political takeover in Bolivia, in part to secure lithium reserves for global markets, including for his own Tesla cars and SpaceX project, tweeted: ‘We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.’Vijay Prashad and Alejandro Bejarano, ‘“We Will Coup Whoever We Want”: Elon Musk and the Overthrow of Democracy in Bolivia’, CounterPunch (Petrolia, CA), 29 July 2020. https://www.counterpunch.org/2020/07/29/we-will-coup-whoever-we-want-elon-musk-and-the-overthrow-of-democracy-in-bolivia/. Performing the hegemonic futurity to which we’re all tethered, Musk pushes extractive colonial capitalism into any and all territories, including outer space, as well as into infinity (thankfully that situation has been reversed in the recent Bolivian elections)'.

But that entails destroying the lands, waters and life chances of frontline communities worldwide, producing a growing class of the indebted, vulnerable and disenfranchised, subjected to all manner of police violence, incarceration and growing deaths of despair, on top of mounting climate disasters, existential insecurity and pandemic emergency. Given the resulting desperation, our forlorn present has triggered blunt expressions of time resistance, like Alisha Wormsley’s ‘THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE’, placed recently in halting all-cap white letters on a black billboard in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as well as on various artistic objects, sculptural pieces, installations and in films.‘“There Are Black People in the Future”: An Interview with Artist Alisha B. Wormsley’, Public Books (New York City, NY), 11 December 2019. https://www.publicbooks.org/there-are-black-people-in-the-future-an-interview-with-artist-alisha-b-wormsley/. Wormsley’s revolt against being de-futured, elaborated in a proleptic tense of the present-impending – a chronopolitics of prefiguration – resonates with the ongoing battles over public monuments and their removals. These highlight the otherwise suppressed violence of colonialism and slavery and their aftermath, past and present conflicts over heritage inextricable from the very social production of the future, which also index the stakes of documentary today. Who has the right to produce the future?

Alisha B. Wormsley, There Are Black People in the Future. Part of Manifest Destiny, curated by Ingrid LaFleur. Image by Alessandra Ferrara, Courtesy of Library Street Collective, Detroit

Radical futurisms have arisen in recent years to assert this right, articulated through speculative visions of times to come. As witnessed internationally in the formation of creative practices pledged to decolonising the not-yet, these rescue open potentiality from the grips of capitalism’s algorithmic capture, its technogenic determination and its biosecurities of control. Building on the precedents of Afrofuturisms of decades past – when Black sci-fi and musical experimentation projected an emancipated, technological presence in years ahead, as fictionally dramatised and historicised in Black Audio Film Collective’s film Last Angel of History of 1996 – these practices now generate new configurations of documentary in multiple sectors, including those of Indigenous futurisms, trans and queer futurisms and multispecies and socialist futurisms, and more.

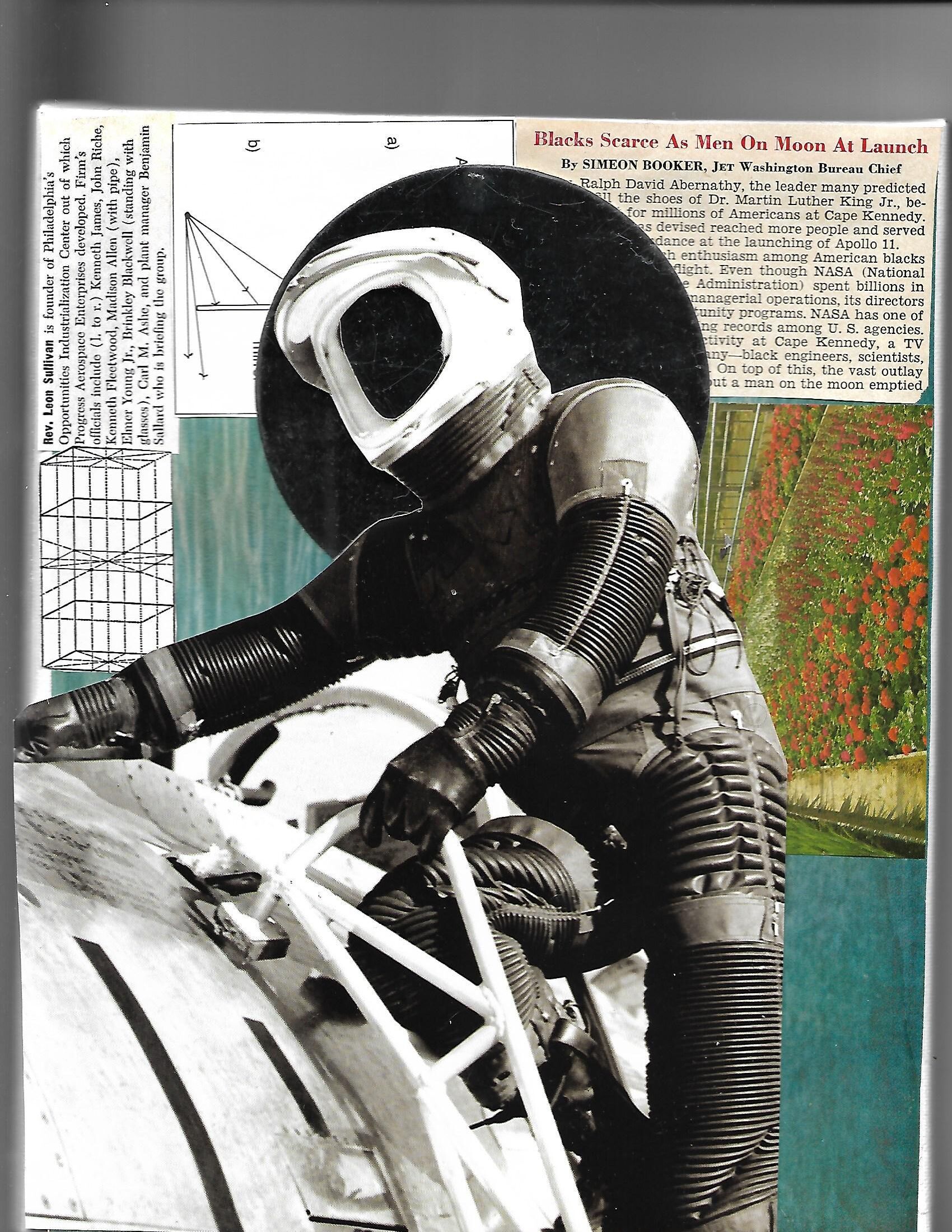

One modelling is BQF’s documentary chronopolitics, which materialise video assemblages and photomontages that unleash the force of radical reversibility. They target time zones that keep racialised bodies locked in oppressive cells fortified by all manner of temporal encasements: unchanging pasts, presences of indolence and criminality, de-futured voids. From these, they break out. As with their 2019 video Black Space Agency Training Video, overlapping images blur into illegibility, shapes mirror and mutate, mimicking soundscapes filled with echoes and reverberations, all emanating from a deep psychic space of traumatic collective memory in the afterlife of slavery and in the recent past of housing segregation. Foregrounded as well in the experimental music of BQF-member Camae Ayewa, also known as Moor Mother, sonic elements perform, like their visual analogues, as so many fugitive elements, oftentimes ripped from appropriated sources of violence. Some are sourced from deadly encounters with anti-Black police brutality, as with the sound piece The Afterlife of Events – Time Distortion, 2016, with its torturous audio, mixed with brutalist electronica, re-presenting Sandra Bland’s violent arrest by police in Texas before her suspicious death in jail. ‘We believe that astrological events are reversed and act retrocausally from the cosmic future to influence present events that will be subsequently written on the fabric of the past by light and sound.’On the “afterlife of slavery,” see Saidiya V. Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey long the Atlantic Slave Trade (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008). Such is a recipe for futurism’s transformative power in the present.

Film still. Black Space Agency Training, Black Quantum Futurism, 2019

With Black Space Agency and associated collages, BQF graphs the techno-optimism of past space travel, dramatised in astronaut iconography and mirrored helmets reflecting Black faces, onto newspaper clips reporting unfulfilled urban housing justice dreams, resonating with the goals of BQF’s Community Futures Lab in North Philadelphia (where member Rasheeda Phillips works as a housing rights lawyer). Their cultivation of spatial agency is juridico-political and geographical as much as aesthetic and temporal. Indeed, the challenge is how to constellate their pulsating lights and sounds to gain the future they want, ripped from the contradictions of racialised inequalities in resource allocation, as their video quotes Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as valid today as it was in 1966: ‘There is a striking absurdity in committing billions to reach the moon where no people live…while the densely populated slums are allocated miniscule appropriations.’

Those uneven geographies are also upended in Cuthand’s Reclamation, resonating with the resounding world-historical project of decolonisation as demanded by Indigenous formations like Idle No More and, more recently, The Red Nation. For them, decolonisation represents the abolition of dominant economic arrangements and socio-political systems organised around extraction and exploitation, bringing to an end more than five hundred years of colonial history and making way for future collective emancipation. The video’s performative power constructs its subjective viewership: an emancipated people-to-come on land evacuated of oppressors, which bears on how solidarity might operate today (particularly in settler-colonial territories like North America), including in documentary practice. Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang have argued that non-native solidarity with Indigenous emancipation must avoid what they term ‘settler moves to innocence’, goodwill ally gestures that practice the metaphorisation of decolonisation by denying its essential meaning: the return of land and sovereignty to Indigenous peoples. Without anchoring those superficial gestures in that latter’s radical meaning, metaphorising acts—which facilely extend decolonisation to this and that, whether decolonising the university or sexuality (as necessary as those also are)— ‘problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity.’Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, ‘Decolonization is not a Metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1, no. 1 (2012): 1, 10. http://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/18630/15554.

Ultimately, for Tuck and Wang, settler accomplices can only accept an ‘ethic of incommensurability’ when it comes to solidarity, ‘relinquishing settler futurity, abandoning the hope that settlers may one day be commensurable to Native peoples’, which in turn requires an ‘understanding of uncommonality that un-coalesces coalition politics.’Tuck and Yang, ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, 36, 35. Accepting uncommonality leaves us recourse to alternatives like those presented in radical Black praxis, dedicated to the undercommons and a permanent fugitivity (as elaborated by Fred Moten and Stefano HarneyThe ‘undercommons’ designates a modality of critical comportment, of fugitive planning and Black study, informed by the Black Radical Tradition, a place of mobile belonging for the excluded, those aware of the contradictions of the university, and society more broadly, in the grips of neoliberalism. Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study ((New York: Minor Compositions, 2013).), where the refusal of property and possession – of land as much as conventional subjectivities – is the ethical truth of emancipated social experience and the only possible basis for decolonial solidarity.Tuck and Yang, ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, 28. That’s exactly what Cuthand’s radical futurism offers to non-Indigenous viewers via documentary form: a subjective non-place, dispossession and permanent fugitivity, and this precisely because the decolonised what’s-to-come is devoid of settler colonialism’s oppressive subjects. With the video, non-Indigenous viewers experience their own disappearance. They become accomplices in the abolishing of whiteness as a structure of racial division and colonial oppression.See Viewpoint Magazine’s collection of texts, ‘Beyond Guilt and Privilege: Abolishing the White Race’, 5 August 2020, https://www.viewpointmag.com/. To enact this abolition grammatically, I have chosen to render white/ness in lower-case as a political revolt on the level of style.

That said, one might argue conversely that demetaphorising decolonisation shouldn’t end in the ‘un-coalescing of coalition politics’ but rather reveal new forms of solidarity on that basis. Indeed, there’s an urgent need for such alliances now more than ever – given present hyper-partisanship, social media atomisation and ethnonationalist reaction – in order to build collective power to disrupt the constancy of colonial capitalist violence that harms us all, if differentially, socio-politically and economically. Writing from yet another radical Indigenous perspective, Nick Estes of The Red Nation argues that Indigenous futurity is and must be ‘universal’: it ‘isn’t just for Indigenous people – it is essential for the very existence of life on the planet.’Nick Estes, ‘A Vision for the Future’, Art Canada Institute (Toronto, ON), January 2020. https://aci-iac.ca/the-essay/a-vision-for-the-future-by-nick-estes. What’s required is a ‘social revolution that turns back the forces of destruction…uniting Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in common struggle’ against capitalism and colonialism.Nick Estes, ‘A Red Deal’, Jacobin (Brooklyn, NY), 6 August 2019. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/08/red-deal-green-new-deal-ecosocialism-decolonization-indigenous-resistance-environment.

Film stills. The Otolith Group, INFINITY Minus Infinity, 2019. Courtesy and copyright the artists

Instead of uncoalescing alliances of difference, another option is unifying in support of their abolition, which documentary might also abet. At this speculative limit is Infinity Minus Infinity, the Otolith Group’s 2019 film linking racial capitalism with the colonial genocide perpetuated during the Anthropocene’s beginnings in the sixteenth century conquest of the Americas. Their genealogy builds further to the hostile environment of recent British immigration policy, especially that affecting the Windrush generation of migrants living both in the afterlife of slavery and in the post-colonial wake of empire (the Windrush generation referring to those arriving in the United Kingdom from Caribbean islands between 1948 and 1971, only to have their residency status questioned and even rejected decades later by recent British xenophobic migration policies). The film’s cinematic allegory traces these complex historical networks as mediated by performance, dance, recital and historical truth-telling spoken by figures who appear as trans-temporal deities. With them, the video choreographs what the artists call a ‘choreo-poetics’—approximating an aesthetic form of collective speech—the script drawn from diverse sources, including the writings of Jamaican poet Una Marson, Martiniquan philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant, Brazilian sociologist Denise Ferreira da Silva and British geographer Kathryn Yusoff.Choreopoetics derives from the “choreopoem” aesthetics of Ntozake Shange, for whom, inspired by the Black Arts Movement in the US, it characterized innovative dramatic expression of poetry, dance, music, and song emphasizing affective response. The term was coined by Shange in her 1975 theatrical piece For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf. Thanks to Kodwo Eshun for this reference. One central character appears many-headed, an Indo-futurist trope signalling multiple realities, a future of many futures, in a time-splitting act of metaphysical and even cosmopolitical import.

With Ferreira da Silva, the artists speculate about a Blackness beyond capture, an infinity beyond infinity, in the place of the subjectivity long denied to those of the African diaspora by European Enlightenment modernity. Documentary is consequently keyed to a future indeterminate, to the ultimately uncapturable zone of the decolonised fugitive. Ferreira da Silva discusses Blackness as antimatter, ‘negative life – that is, life that has negative value’ and instrumentalised historically by Europe’s ‘universal measure’ in defining whiteness as its counterpoint and the height of self-actualising reason.Denis Ferreira da Silva, ‘1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value’, eflux Journal, February 2017, 8. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/79/94686/1-life-0-blackness-or-on-matter-beyond-the-equation-of-value/. The latter, fortified by racial oppositions gained through colonisation and enslavement, with all of the sociological, economic and representational violences that were cause and consequence of that inequality (including a long history of documentary anthropology). From its negative use-value to white reason and the dialectics of race, Blackness, in Ferreira da Silva’s deconstruction, opens onto indeterminacy, topologically connected to the infinite and uncontainable—approximated in Infinity Minus Infinity by turning the ears, eyes and fingernails of figures into corporeal portals to other worlds. This is accomplished through a kind of biopolitical montage in which bodily orifices and surfaces provide screens of layered videos within videos, revealing ever-new scenes from the racial Capitalocene (the geological epoch shaped by colonial capital, offering a more precise descriptor than the AnthropoceneT. J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017); and Françoise Vergès, ‘Racial Capitalocene’, Verso blog, 30 August 2017. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3376-racial-capitalocene.). Defining a documentary of allegorical immensity, the film’s voice-over culminates by speculating about an eventual future resolve of liberation, though ‘only when those myths have been incorporated one into another and recognized as constituent parts of the before- and after-life of slavery and the never-ending colonial project.’

Reverberating with Cuthand’s Reclamation as well as BQF’s layered chronopolitics, the video’s performative documentary proposes something like an abolitionist double negative: both catalysing (1) a disidentification not only from white supremacy but from the very logic of racial difference, and (2) compelling the nullification of the very systems—the legal and economic institutions, the techno-social and educational infrastructure, the affective and aesthetic practices—that have reproduced it historically and into the present.As was discussed in the Burning Futures podcast series, organised by Margarita Tsomou and Maximilian Haas, HAU Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin, #5 Beyond The End Of The World?, with T. J. Demos and The Otolith Group (Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun), 23 June 2020. https://burningfutures.podigee.io/5-beyond-the-end-of-the-world. It’s only appropriate, then, that the Otolith Group, in seeking to grant aesthetic form to this complex movement of a deeply historical futurism, find recourse in the imagery of two black holes colliding, creatively adopting a recent computer simulation from the California Institute of Technology that shows that awesome astronomical event detected for the first time ever by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.Animation created by the Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes project (http://www.black-holes.org), https://www.ligo.caltech.edu/video/ligo20160211v3. Roughly 30 times the mass of the sun, each contains a gravitational singularity wherein space-time curves infinitely. The film operates in the time-space between those two black holes: after a past of unforgivable debt in the afterlife of slavery and facing a future filled with indeterminacy beyond reified difference. Its many portals reveal a not-yet of radical disruption from a history that must be obliterated but never forgotten. At its best, speculative documentary unleashes cosmopolitical force and provides the building blocks – forms, events, affects and poetics – of new worlds; the challenge remains to organise the social movements to bring them into actuality.