Unknown photographer, Paper Processing. Sorting at format cutting machines, December 1956, Color photograph, Museum Ludwig, Agfa Werbearchiv, Detail

Porous surfaces: Hands, chemicals, and the material lives of photographs

Trigger invited writer and historian of photography Siobhan Angus to engage with Entropic Records, a new book by artist and researcher Pauline Hafsia M’barek because of Angus’s ability to make the material life of photography both visible and compelling. In her book Camera Geologica, Angus traces photography back to minerals, chemicals, and deep geological time, a perspective that closely resonates with M’barek’s practice. Entropic Records emerged from M’barek’s work with the AGFA advertising archive at Museum Ludwig in Cologne and was presented in 2025 as part of the Artist Meets Archive programme at the Internationale Photoszene Köln. Rather than offering a conventional book review, Angus’s essay invites readers to look differently, approaching photography as a tactile, fragile surface shaped by hands, labour, chemistry, and time.

Siobhan Angus

10 feb. 2026 • 13 min

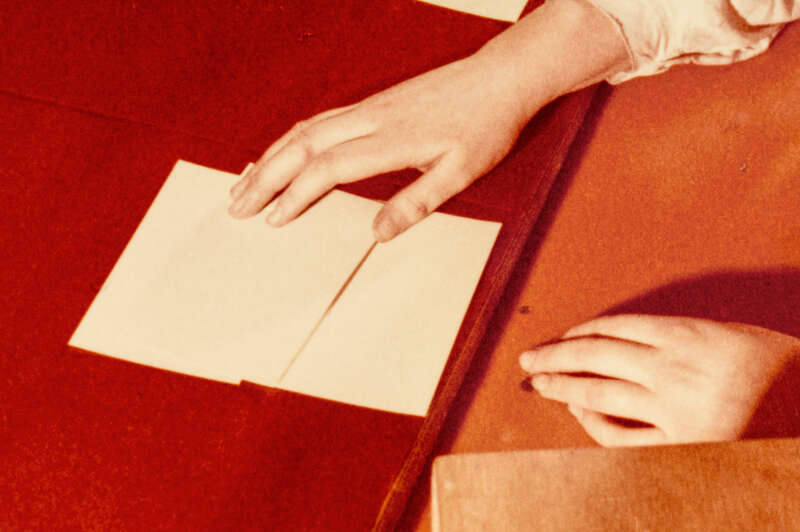

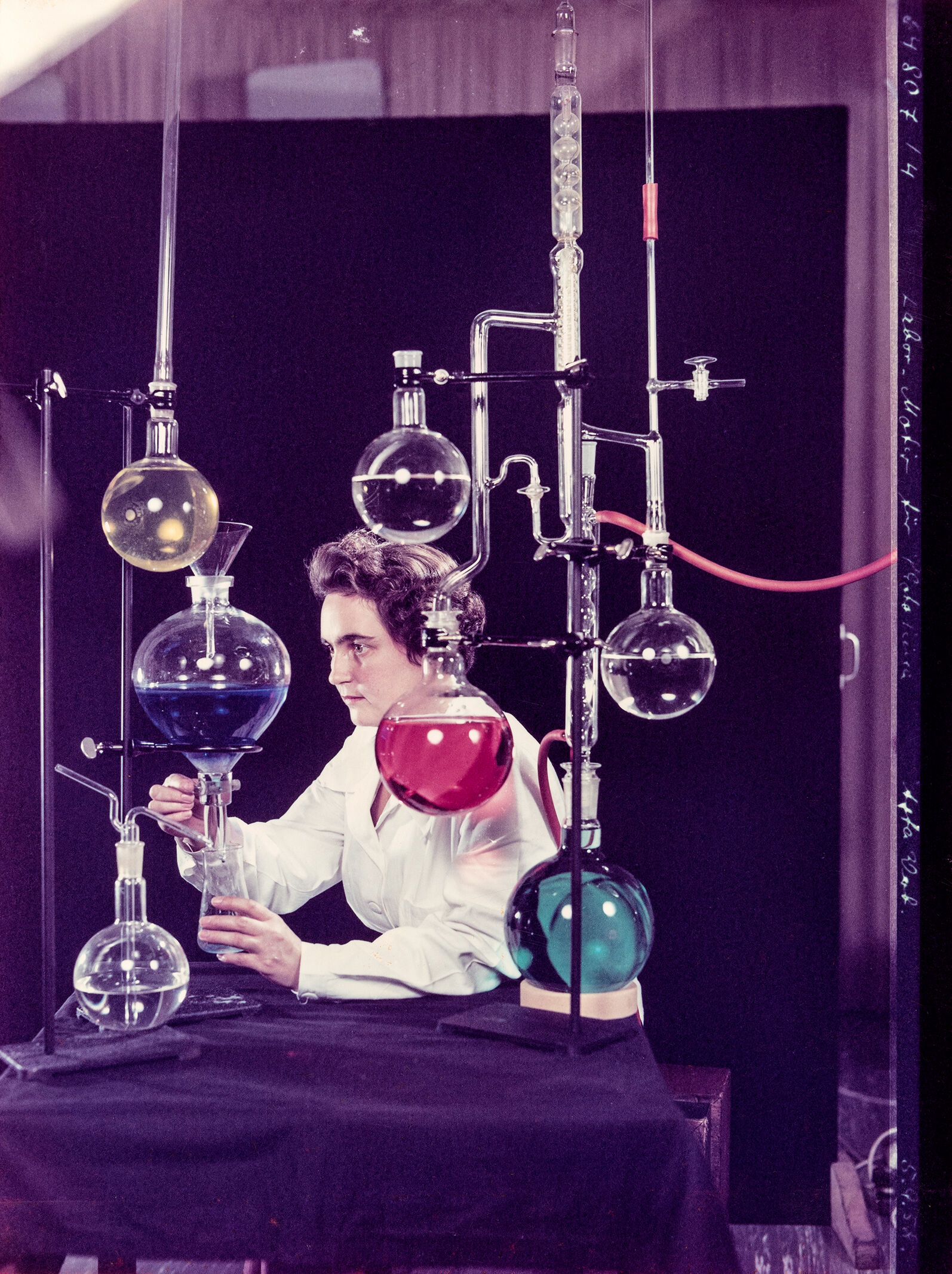

Unknown photographer, Paper Processing. Sorting at format cutting machines, December 1956, Color photograph, Museum Ludwig, Agfa Werbearchiv

Touch

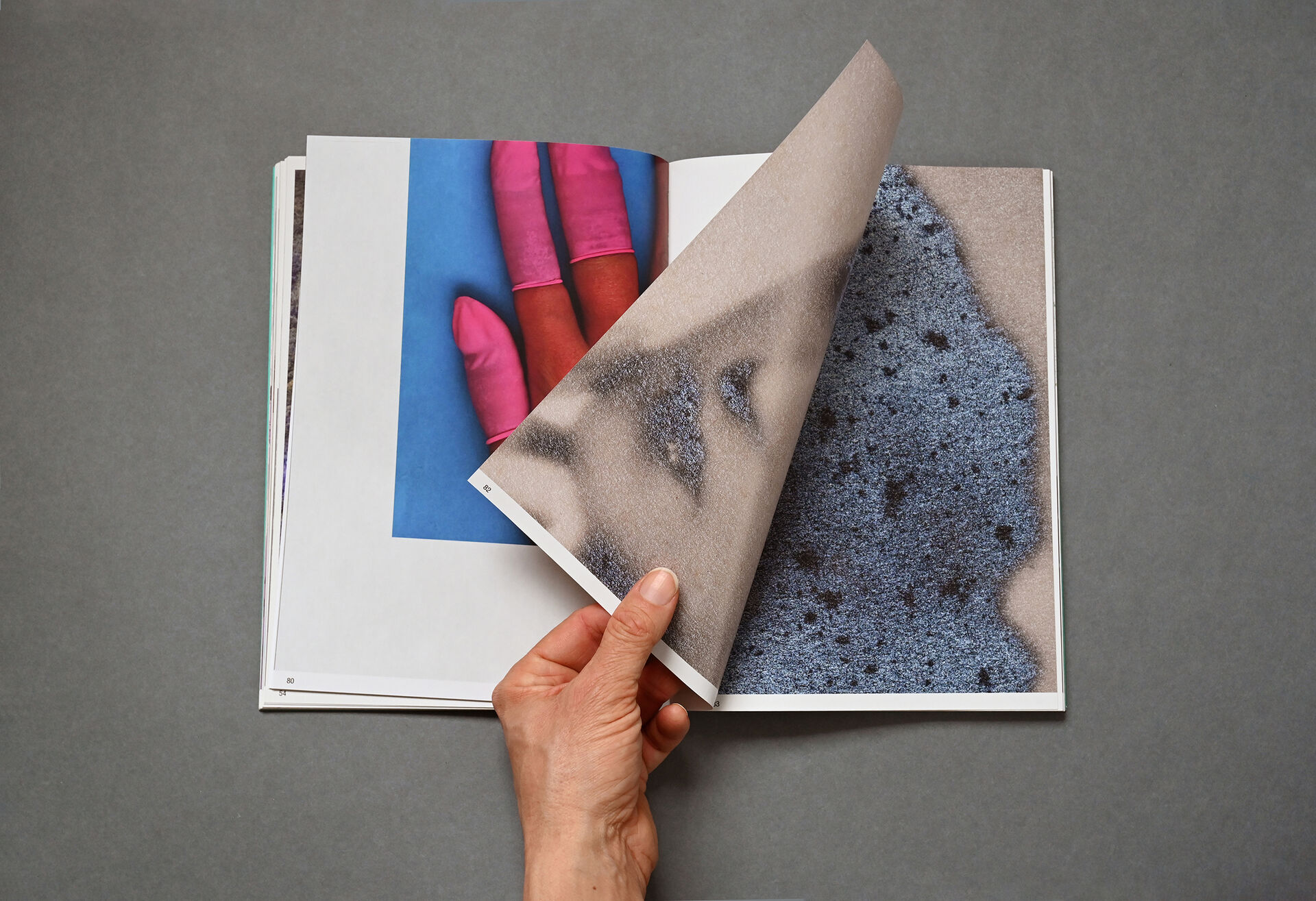

I notice hands first. They appear repeatedly in Pauline Hafsia M’barek’s Entropic Records: holding paper, mixing chemicals, resting on work surfaces. Two hands on a saturated red surface, one pressing a white sheet of paper – a scene both abstract and enigmatic. I turn the page; the image zooms out to reveal a woman in a white coat and hairnet. The embodiment of efficiency in a clean, controlled workspace. She sorts papers at a format-cutting machine in a scene from 1956, part of AGFA’s industrial photographic archive held at the Museum Ludwig. The image telegraphs cleanliness, efficiency, and control.

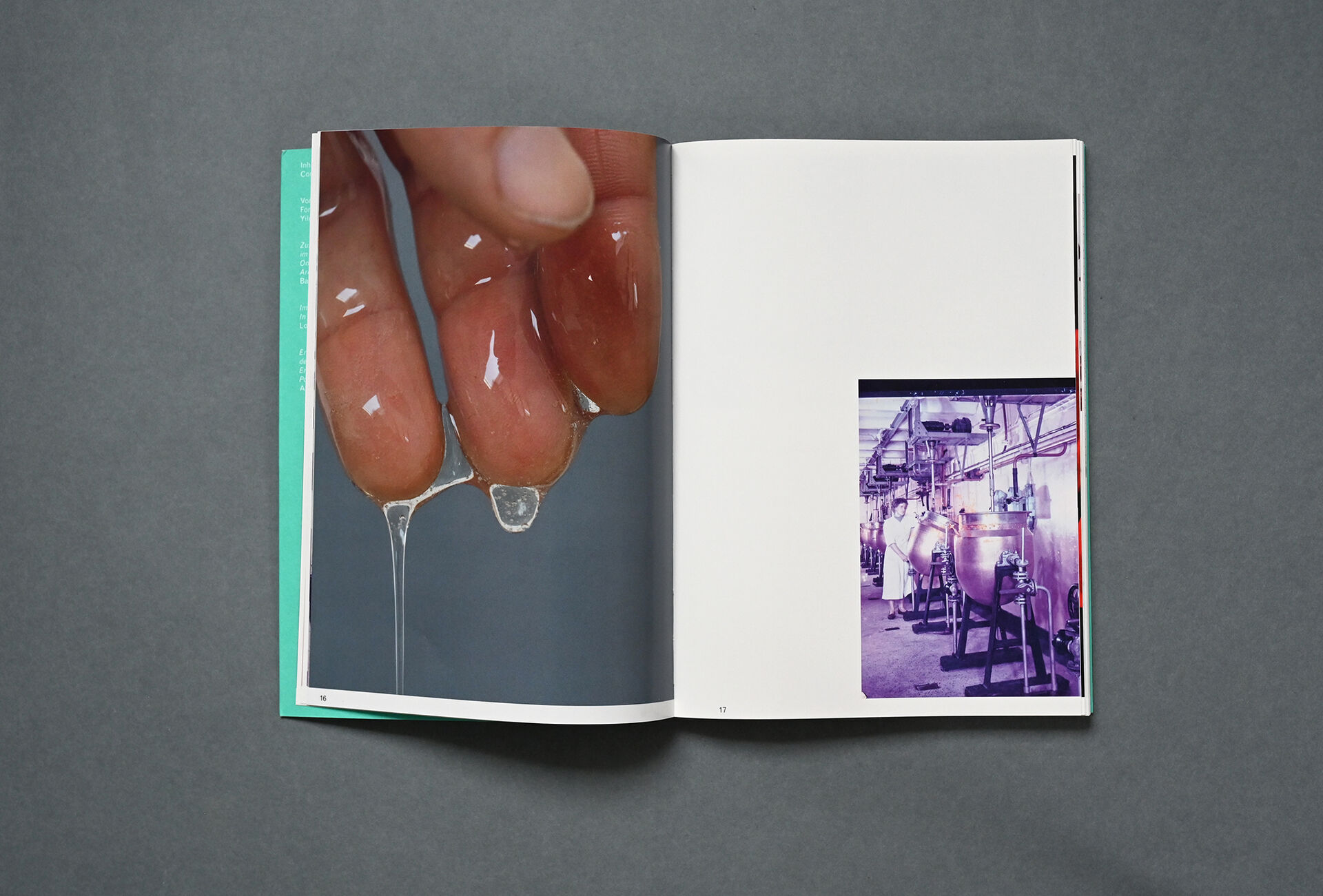

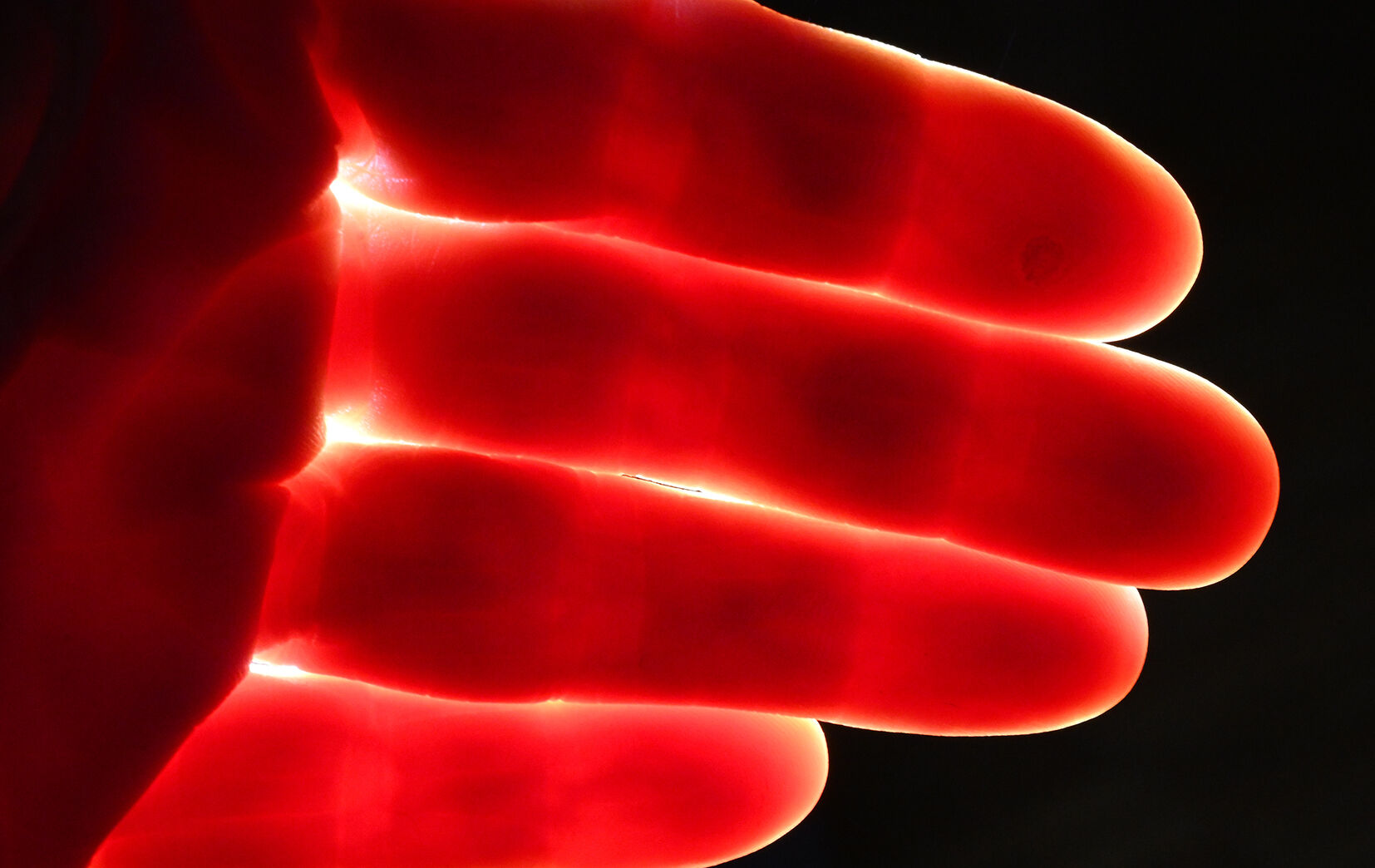

And then, more hands – workers mixing materials and holding beakers; the gloved hands of the artist–researcher or archivist. Hands do not illustrate labour so much as register it. The hand becomes a point where image, body, and material process meet. M’barek weaves the archival AGFA photographs with her own images, creating a dialogue between archival histories and contemporary observation. In Untitled (Aperture), close-up images capture light illuminating hands – the hand as threshold to transition, revelation, or exposure. Exposure functions here in two ways: the exposure of the image and exposure to toxicity. A hand drips with photographic gelatin; eczema marks the hands of a photographic factory worker, the result of chemical exposure – irritated, worn, stained. Hands reveal porosity.

Unknown photographer, Photo factory, barite preparation, 17.12.1956 / December 17, 1956, Color photograph, Museum Ludwig, Agfa Werbearchiv, 59002/35b

Pauline Hafsia M’barek, Untitled (Aperture), 2025, Color photograph

In photographic production, chemical precision depends on bodily vulnerability. From its earliest years, photography was entangled with chemical risk. Exposure accumulates, registering as inflammation, sensitivity, and damage. In 1864, the Photographic News named disease among the profession’s ‘special dangers’, pointing to the persistent dismissal of chemical hazards by medical authorities, despite repeated warnings from practitioners.‘The Health of Photographers’, Photographic News 8, no. 312 (26 August 1864): 409. For a broader analysis of these histories, see Siobhan Angus, Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography (Duke University Press, 2024), 124–28; Jennifer Tucker, ‘Dangerous Exposures: Work and Waste in the Victorian Chemical Trade’, International Labour and Working-Class History 95 (July 2019): 130–65. The body is an archive of industrial processes and chemical toxins. While the archive preserves images of labour, bodies retain its residue, carrying knowledge that never appears in captions or metadata.

Eczema from chemicals on the hand of a photographer, wax cast from life 1980-90 (original cast 1900-12) / Wax mixture, fabric, paint, Stiftung Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden

As I study the images, I’m unsettled by the porosity of both the photographic surface and the worker’s skin. Both act as an embodied archive, registering the passage of time, industrial processes, and chemical exposure. The photograph, like the hand, is shaped by what it touches. To attend to these traces is to accept that photographic meaning doesn’t reside only in what is shown in the image as representation, but in what has passed through matter, leaving its mark. Throughout Entropic Records, hands disrupt the sterility of the industrial archive, returning attention to scale, contact, and risk.

M’barek’s evocative exploration of the Museum Ludwig’s AGFA archive began through the Artist Meets Archive programme organised by the Internationale Photoszene Köln. The resulting exhibition and book trace a history that moves from the intimate touch of hands and the vulnerability of the body through the ordered systems of museum archives and industrial chemical processes. It then extends outward into vast temporal flows of entropy and geological time, revealing how photographs index labour, matter, and history into a single, active surface. This shift between registers functions both visually and conceptually as M’barek manipulates zoom and scale, moving from the microscopic details of materials and images to the broader industrial and archival environments, revealing connective tissue between bodies, images, and vast systems of production.

Pauline Hafsia M’barek, Minutiae, 2021, Video, 4K, Color, 2:30 min, Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Rehbein Gallery

Archive

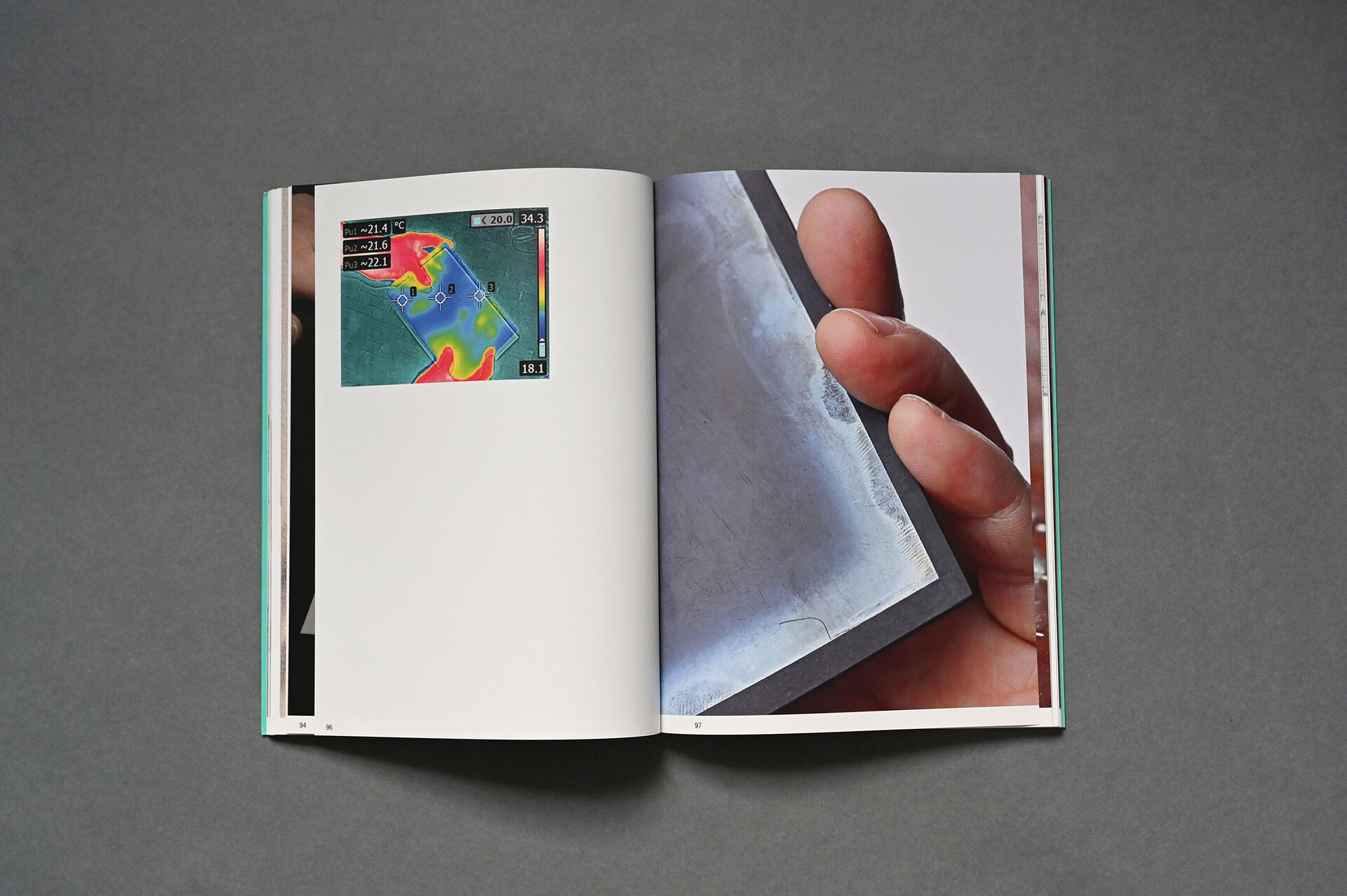

Within the archive, the image surface is protected while the history of bodily exposure recedes. Yet hands remain both a challenge and a mode of access, reminding us that the surface is never inert. Oils, humidity, and heat pass between body and object. Iridescence marks the trace of fingerprints in the silver gelatin print, where contact has altered the material’s chemistry. While residues left by the fingers can initiate processes of decay, the oils contained in fingerprints may also exert a protective effect, inhibiting the migration of silver to the image surface. As Lotte Arndt notes, touch does not function solely as a destructive force but can, under certain conditions, slow visible deterioration.Lotte Arndt, ‘Preservation by Touch’, in Entropic Records: Pauline Hafsia M’barek ed. Barbara Engelbach (Walther König, 2025), 125. Chemical discolouration marks the rupture of the contained surface. Preservation protocols attempt to interrupt this exchange, but the photograph arrives in the archive having passed through many hands, each leaving traces.

M’barek’s attention to hands made me reconsider my own frustration at being directed to view a digital image rather than the physical object in an archive. Entropic Records makes a case that some knowledge emerges only through material encounter – through touch, weight, and surface – that no screen can fully convey. The tactile engagement reveals dimensions of the photograph that digital reproduction cannot replicate. Photographic knowledge is not only optical but tactile – learned through handling and exposure rather than observation alone.For an analysis of photography’s haptic dimensions, see Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Duke University Press, 2012); Margaret Olin, Touching Photographs (University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Yet touch poses a risk to photographs. Instructions urge caution: gloves on, sometimes gloves off; pressure minimised; touch reduced to a controlled gesture. The archive frames touch as danger but the book reveals that photographs are already products of touch – mixed, coated, lifted, washed, and dried by hands exposed to chemical processes. Touch and handling reveal the intimate link between the body and the chemical processes that give photographs their material and visual life.

While the archive frames touch as both a mode of knowledge and a potential risk, it also foregrounds the material and chemical processes that make photography possible. To understand photographs as active, reactive surfaces, one must consider not only the traces of human handling but the chemical forces that shape, alter, and animate the image.

Unknown photographer, Laboratory shot for photokina, 5.9.1958, Color photograph, Museum Ludwig, Agfa Werbearchiv

Chemistry

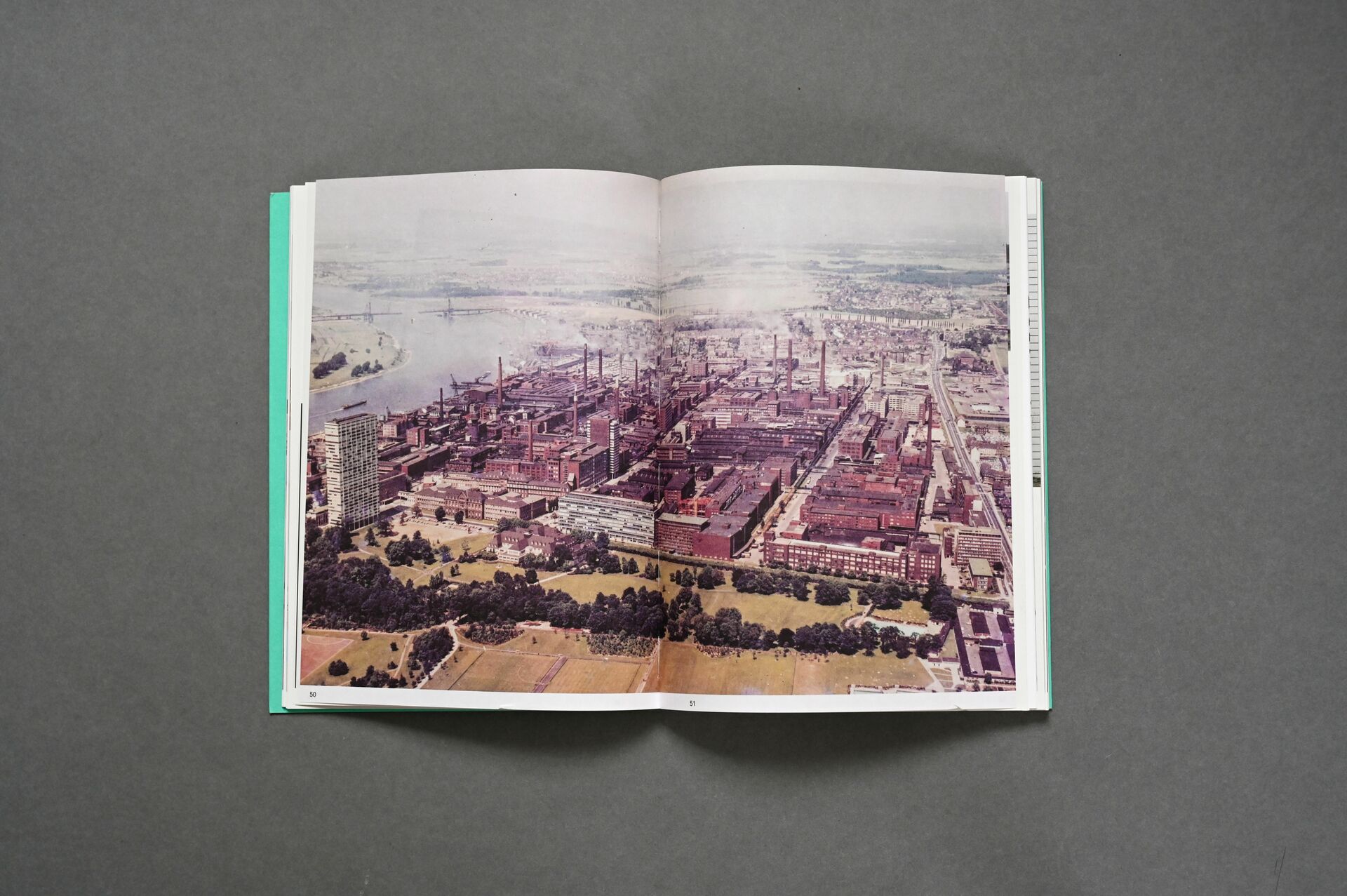

Entropic Records centres on the AGFA advertising archives held at the Museum Ludwig.For a history of the AGFA archive, see Barbara Engelbach, ‘On the History of the Agfa Advertising Archive at the Museum Ludwig’, in Entropic Records: Pauline Hafsia M’barek ed. Barbara Engelbach (Walther König, 2025), 57–72. Founded in 1867 in Germany and originally named Aktien-Gesellschaft für Anilinfabrikation (Corporation for Aniline Production), AGFA began as a chemical company focused on synthetic dyes. These vibrant, affordable colours were derived from aniline extracted from coal tar. As the company expanded into photographic products and technologies, chemistry remained foundational.

An analogue photograph is a convergence of organic, inorganic, and synthetic materials: cellulose and gelatin entwine with glass, silver, copper, and myriad other materials, each element performing its part in a delicate choreography.A growing body of work has explored photography’s material histories, including Boaz Levin, Esther Ruelfs, and Tulga Beyerle, eds. Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production (Leipzig: Spector 2022); Robin Kelsey, ‘Photography and the Ecological Imagination’, in Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment, ed. Karl Kusserow and Alan Braddock ( Princeton University Art Museum, 2018), 394–405; Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, Camera, Natural Resources (Rutgers University Press, 2012); Nicole Shukin, Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (University of Minnesota Press, 2009); Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Katherine Mintie, ‘Material Matters: The Transatlantic Trade in Photographic Materials during the Nineteenth Century’, Panorama 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020); Jennifer Raab, ‘The Art of Alchemy: Golden Pictures, or, Turning Extractive Capitalism into American Individualism’, in El Dorado: A Reader, ed. Aimé Iglesias Lukin, Tie Jojima, Karen Marta, and Edward J. Sullivan (Americas Society, 2024), 72–81; Katerina Korola, ‘Verre et poussière. L’hygiène photographique à l’ère industrielle’, Transbordeur. Photographie histoire société 8 (2024): 52–65. Yet it’s the chemicals – dyes, developers, fixers –that animate these materials. Photographs capture the agency of chemical forces – forces that shape, alter, and intervene in the material world.For chemical histories of photography, see Alice Lovejoy, Tales of Militant Chemistry (University of California Press, 2025); Katherine Mintie, ‘Compositions chimiques. La photographie et le commerce mondial des produits chimiques au tournant du XXe siècle’, Transbordeur. Photographie histoire société 8 (2024): 40¬–51; Michelle Henning, A Dirty History of Photography: Chemistry, Fog, and Empire (University of Chicago Press, 2025). Over time, these light-sensitive substances retain the marks of their making, bearing the subtle traces of creation and decay. As Jane Bennett argues in Vibrant Matter, a work cited by M’barek, matter is never inert; it vibrates with life and agency.Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2010).

Despite the unruly materiality of analogue images,Jeff Wall, ‘Photography and Liquid Intelligence’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. Peter Galassi (Museum of Modern Art, 2007), 109–110. the chemicals industry developed a visual language rooted in containment.Siobhan Angus, ‘Ansel Adams at Union Carbide: Extractive Capitalism’s Wellsian Worlds’, forthcoming in American Art, 2026. Raw materials were isolated, combined, and manipulated into formulas that bore little resemblance to the materials that made them. In the AGFA archives, the gestures of pouring, mixing, and measuring repeat across the images, rendering the often-invisible forces of chemistry legible. A woman mixes colourful chemicals in circular glassware. The scene conforms to a familiar advertising iconography, in which photochemistry appears as a controlled and harmless manipulation of colour. The overt mise-en-scène, visible in the background, further signals the image’s staged nature. A man in a white lab coat, tie, and dark glasses calmly pours liquid into a tube. Then the factory floor: men prepare barite in large vats.

Here, the fantasy of containment fractures. A flash of orange-red anchors the image’s corner, spreading across a microscopic pattern. Another splash of red cuts through the middle. I’m drawn to the glowing red of the chemical dyes, noticing how they hint at both the human and chemical forces shaping the industrial environment. What was meant to be controlled now asserts itself within the images, erupting as stains, shifts, and blooms. An instrumental image of labour preserved in a corporate archive becomes a stranger document – one that captures the tactile instability of its medium. Marked by decay, the image confronts the twin ideals of photographic permanence and archival preservation.

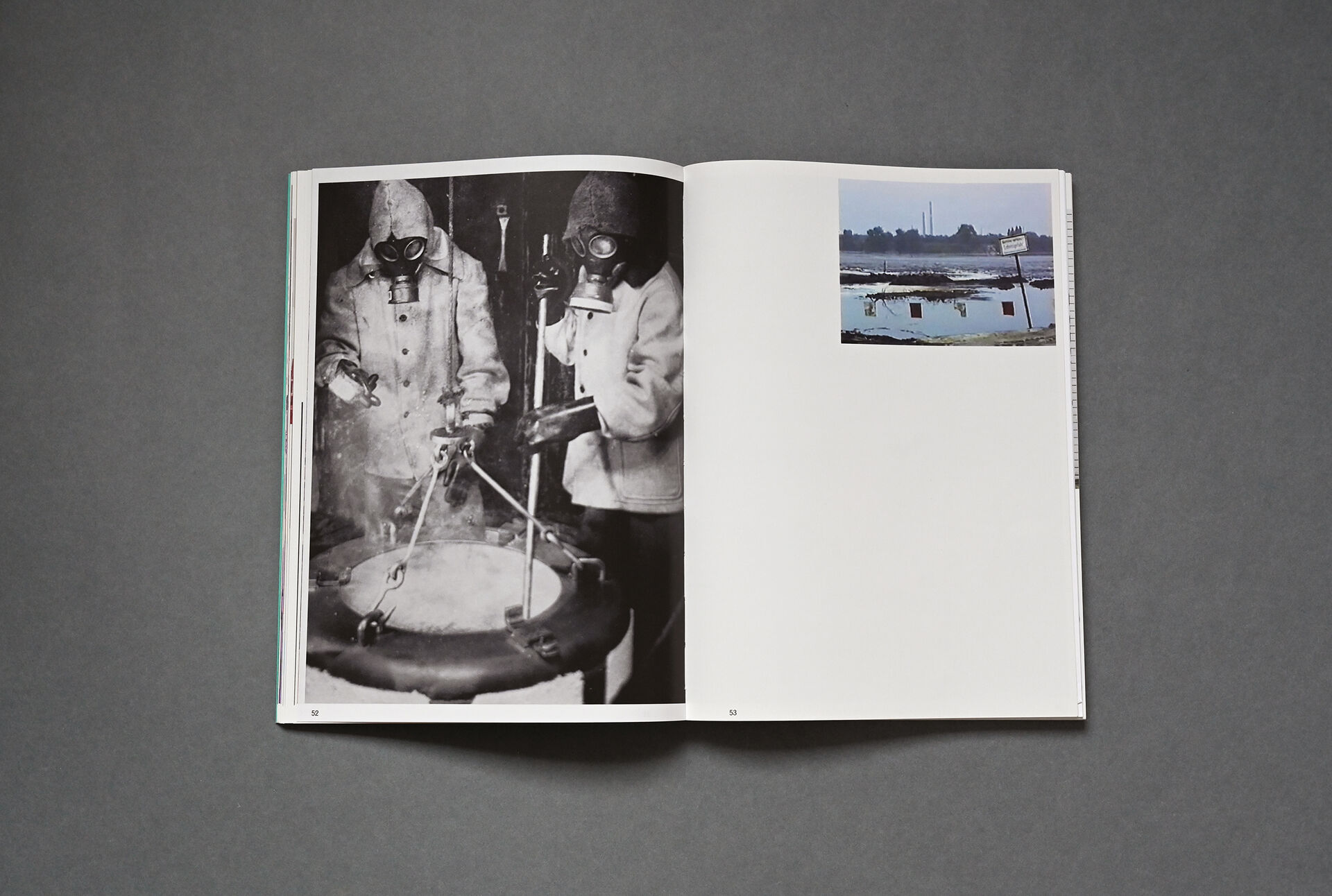

Images of contamination make this unavoidable. A photograph from the Agfa-Gevaert collection, part of FOMU - the Museum of Photography, Antwerp shows two men in gas masks standing over a vat – an unsettling scene seemingly pulled from science fiction. It faces a photograph of the polluted waters of Silver Lake, where AGFA discarded photo-chemical waste in a former open-pit mine. The lake earned its name from the silverish tinge of the chemical residue. The pairing of the images speaks to the impossibility of chemical containment, where even the most carefully controlled processes leak, spill, and spread beyond their bounds.Katerina Korola has written about the histories of contamination at Silver Lake through the photographs of chemist and former Filmfabrik Wolfen employee Fred Walkow and Alexandra Navratil’s 2015 film Silbersee. Katerina Korola, ‘Silbersee: A Landscape Exposed’, paper presented at Chemical Histories of Photography, University of Basel, Basel, 24 October 2025. For a history of water contamination at Ciba, see Stephan Graf, ‘Du Cibachrome relativement toxique. Eaux usées de la photographie et production d’images en couleurs’, Transbordeur. Photographie histoire société, 8 (2024): 66–77.

Entropy

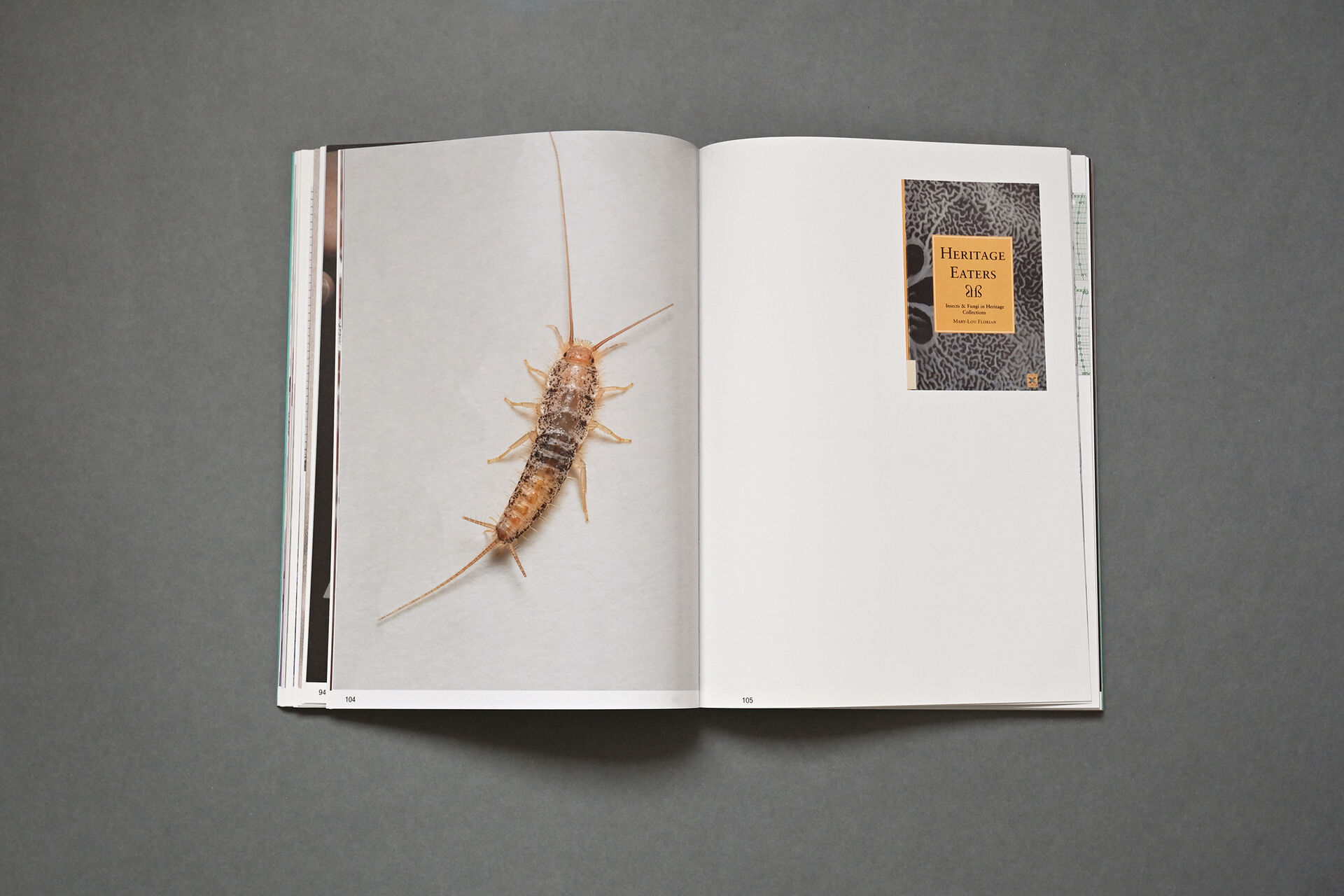

The photograph is always shifting with the fluctuations of temperature, humidity, pollutants, touch. They yield to the slow, inevitable forces of change – silvering, fading, fragility, and the spread of mould. Beneath the surface, chemical processes stir relentlessly, for all matter carries within it the pulse of entropy, a ceaseless drift toward dissolution.

Throughout Entropic Records, stains, mirroring, and discolourations interrupt clarity. The photograph moves beyond its instrumental role as corporate record and becomes a meditation on impermanence. Decay here is not negation. It’s a condition of transformation. For M’barek, entropy names the dissolution of intended meaning, allowing new forms to surface. In archives, decay marks decline; here, it opens other readings. Entropy produces a different kind of knowledge – tacit, embodied, resistant to categorisation. Physical traces act as epistemic agents.

Entropic Records, Museum Ludwig, installation view, Photo: Pauline Hafsia M’barek

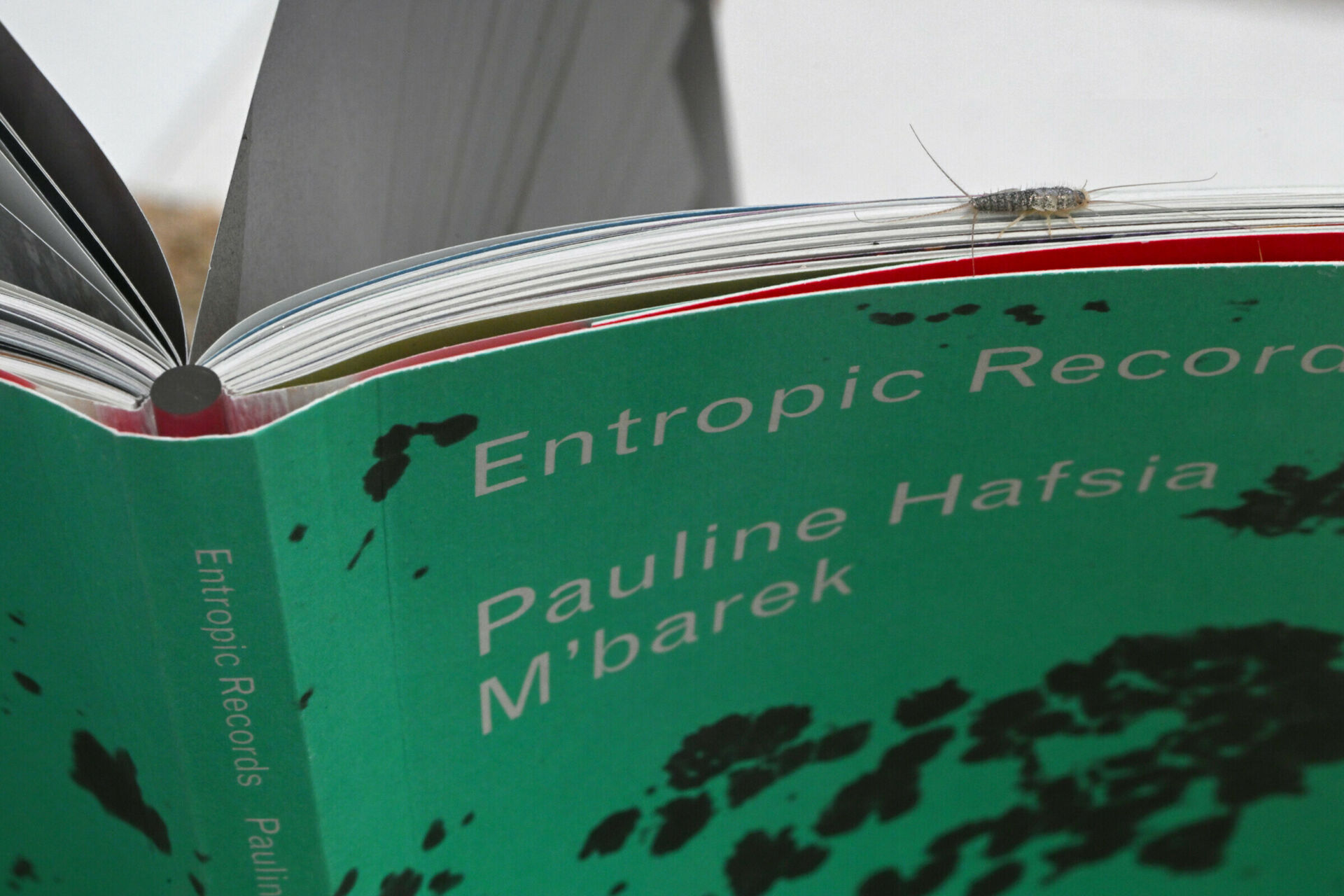

Attention to entropy as an active process extends to the exhibition itself, where the logic of exposure and transformation shapes the presentation of the book within the exhibition. Designed to be consumed by the museum’s insects, its paper, pigments, and binding were chosen with this vulnerability in mind. Entropy emerges here less as an abstract concept than as something enacted materially over time. Dust, insects, moisture, and touch – elements usually excluded from the museum’s controlled environment – enter the work as conditions rather than disruptions, drawing the publication into the same cycles of exposure and transformation that structure M’barek’s engagement with the archive.

Chargesheimer, At the coal, from: in the Ruhr Valley,1958, Gelatin silver print, Museum Ludwig, ML/F, 1981/0369

Entropy also links photography to deeper temporal scales. Rooted in Victorian-era physics, entropy is a concept within thermodynamics, a branch of science that concerns heat, work, and temperature. Thermodynamics itself emerged from a drive to improve the efficiency of early steam engines. The notion of entropy is thus closely tied to processes such as coal combustion.

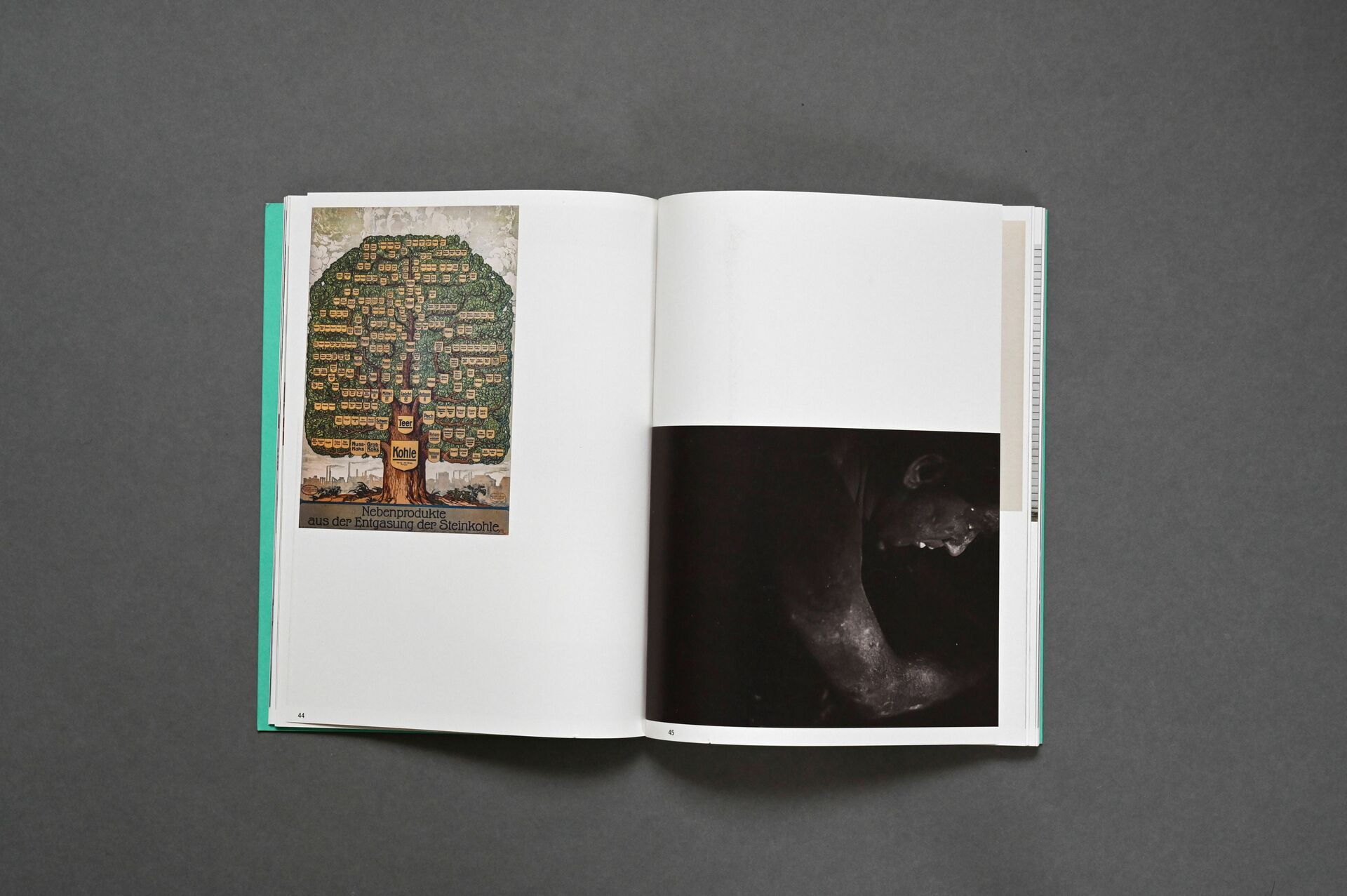

AGFA’s reliance on coal tar situates the archive within a fossil-fuel economy. This is made tangible in one of M’barek’s juxtapositions: opposite At the Coal, in the Ruhr Valley (1958), which features a tightly framed miner coated in dust, a chart titled ‘Byproducts of the Degassing of Coal’ by W. Gross (1920) is superimposed on the drawing of a towering tree, its organic presence looming over the industrial scene in the background. The industrial promise of coal by-products is traced back to its origin in the mine and the labour of the miner, and then even further as coal tar is condensed from coal.

The fossil matter – plants and trees transformed over millions of years – was extracted, refined, and chemically fixed onto the photographic image. In this way, the photograph carries traces of both geological time and industrial transformation: the deep past of fossil carbon intersects with the chemical processes of production, making the image a site where ancient matter and human industry converge.

As I attend to the images, I become aware of what has been extracted and transformed. Preservation attempts to stabilise these surfaces, but chemical bloom reveals what stabilisation suppresses: photography’s entanglement with extractive processes and their consequences. Degradation becomes disclosure.

Colour photography does not merely represent the world; through M’barek’s reframing, it activates geological time. Entropy connects the deep past to the visible surface. While looking, I find myself implicated in that flow. The insistent presence of hands anchors the image in the material world. Images arrive already altered by light, temperature, storage, and touch. Entropy has been at work long before I begin to read. The photograph presents itself as an active surface, still exchanging energy with its environment. Photography emerges here as condensed industrial and geological time, refracted through embodied perception. Meaning resides not only in what photographs show, but in what they absorb, endure, and transform. Reading M’barek’s work, we’re compelled to attend to the photograph as an active, porous surface: simultaneously record, agent, and witness of histories intimate, industrial, and geological.

Entropic books can be bought through the museum shop of Ludwig Museum or ordered through after8books.

Published by Museum Ludwig, 2025

Design by Jan-Pieter Karper

Exhibition Catalogues / Documents / Photography / Media Studies

Siobhan Angus' Camera Geologica can be obtained through Duke University Press.

Pages: 328

Illustrations: 55 illustrations, including 32 in color

Published: March 2024