You came to go, came to go far.

Came to go far [and] bring wood to the river.

But it takes a long time, it is far to the river.

Thank you, friendThe song texts for The Untangled Tales were compiled from Michiel van Kempen, Een geschiedenis van de Surinaamse literatuur (Paramaribo: Uitgeverij Okopipi, 2002); Melville Herskovits and Francis Herskovits, Suriname Folk-Lore (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936); and Jacques Arends, Language and Slavery: A Social and Linguistic History of the Suriname Creoles (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2017).

Songs in a strange land

I write from afar. I am not there where the flags hang. I am not there where the songs linger in the room. I am not there where the hands are still and large, where the dark night is interrupted by a flash of light, where memories hide. But, somehow, I am. Somehow, I am part of this circling and searching and speaking of memories.

My first trip to the Netherlands was in 1979. I was eleven years old. Born in Durban to Dutch parents and growing up in apartheid South Africa, I was both part of a micro-narrative of an immigrant familyI use the term immigrant carefully, with the understanding that my parents intended to stay indefinitely in their new country rather than expatriate, defined as living temporarily outside one’s native country. Often these terms are racially charged and marked with notions of agency and choice. and part of something much greater that tethered my life to the traumatic and lingering legacy of 150 years of Dutch colonial rule in South Africa. Despite having retained Dutch cultural threads at home, my eleven-year-old self experienced this trip as a strange encounter.Sara Ahmed, Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality (Routledge: London and New York, 2000). I spent much of my time looking for home, for traces of the world I knew, looking in paintings and words, in dolls and books and museums, for identities and stories that I could recognise. Somehow, I was not there.

Michelle Piergoelam, too, was born to an immigrant family. Her parents both moved at a young age from Suriname to the Netherlands, where Michelle was born in 1997. Dutch colonial rule lasted almost 300 years in Suriname, twice as long as in South Africa. The stain of colonial domination and cultural exile runs deep, yet threads, fragments, and dreams remain, carried through generations in song, cloth, and myth. Life in the Netherlands for Michelle’s family meant assimilation into Dutch culture, and visible traces of Suriname, such as ways of dressing and language, were smothered. Despite the sustained impacts of cross-generational cultural forgetting, slivers of the rich traditions of Suriname have survived, and can be found in the intangible repertoires of stories told, in songs from afar, and in the intricate folds of cloth.

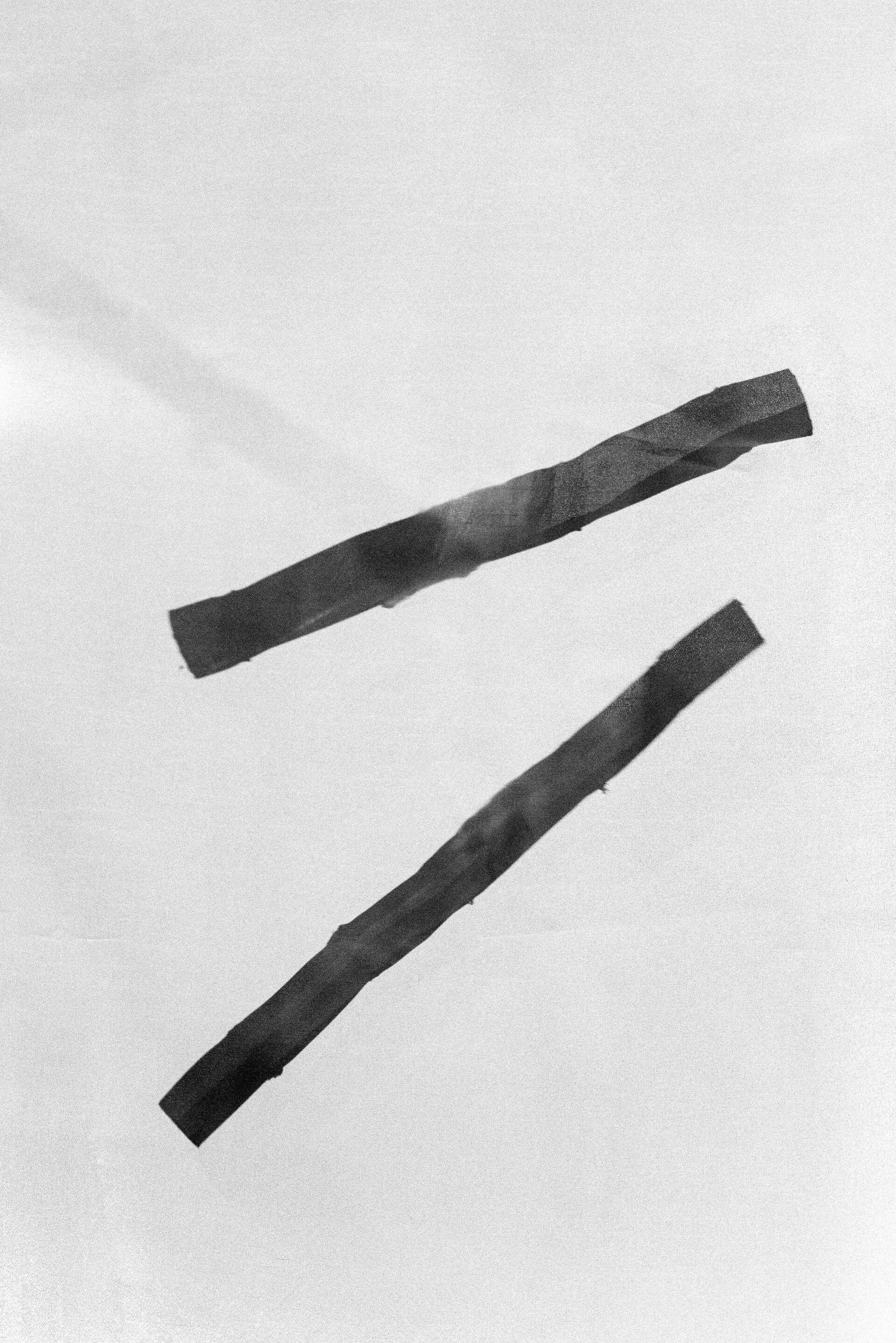

'Cane sugar'. From the series Songs in a strange land, 2022.

Michelle and I met on Zoom to talk about her ongoing multidisciplinary project, The untangled tales. Speaking from Rotterdam, she tells me that, despite her deep yearning to visit, she still hasn’t been to Suriname.Travel plans were interrupted by the pandemic in 2020 and other extenuating factors. Michelle plans to visit Suriname in 2024. And yet, her photographic project brings Suriname into view – or I should say, it brings traces, hints, remnants, and fragments of Suriname into view. Currently on at the Mino Art Space in Antwerp, The untangled tales is an immersive installation of twenty-seven large and small photographs on cloth, curtains, canvas, and archival paper that evoke the place she hasn’t yet visited.

Her photographs are both true and fictitious. The banana leaf, cocoa, and cane sugar found at the local market or spice store are real. They are also metonymic. They speak to histories of colonial trade, slavery, and tropical lands. Their Surinamese bonds are strong yet hidden in plain sight. Michelle’s journey – and yearning – to find Suriname within herself, to make Surinamese culture and histories visible and tangible, propelled a quest to seek Suriname within her surroundings. She shares her hopes for her project: to bring to light the people and their resilience and ingenuity in relation to the long, often hidden histories of slavery. Being Surinamese in the Netherlands, and seeking out songs and unheard stories through photography, is a way of ‘finding her culture in the dark’, making visible that which is absent, and remembering that which is forgotten.

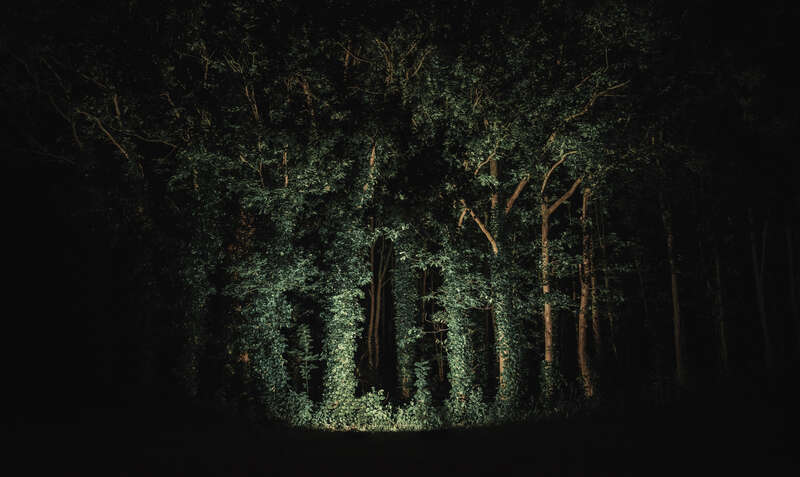

I think photographing in the darkness and putting a light on it reflects how I found Surinamese culture, how its hidden, and how I hope to expose it.Michelle Piergoelam, in conversation with Erica de Greef, 16 May 2023.

Of sonic longings

Songs in a strange land is the second chapter in Michelle’s project, The untangled tales. It’s filled with watery ways, sonic strands, and dark, dreamlike shadows. It features a river, perhaps many rivers, at night. And traces of songs. These are Surinamese rowing songs offered to the water spirit, as blessings that the river, and the route, may be smooth. Infused with cryptic notes about slaveholders and age-old myths, the songs are both laments and acts of resistance. Fragments of these rowing songs are featured in the shredded flags as a part of the exhibition. They are also audible offerings, a submergence in the memories of those once enslaved who transported precious goods on river boats by day, and by night.

Emerging from the darkness, the river is the holder of life and the spirit-world. It bestows gifts that are afloat or washed ashore, carrying echoes of hope. Yet, the night river also holds the unknowable, often haunted with journeys, where screams were silenced, as if consumed by it. As grieving keeper, the whispering dirge of the river fills the night.

For Michelle, the night river photograph becomes Surinamese history. The river becomes the site of memory, the lieux de mémoire.I am pointing to a river’s potential to become vested with historical significance in terms of collective memory through the photograph, using Pierre Nora’s concept of lieux de mémoire. Pierre Nora, ‘Between History and Memory: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, no. 26 (1989): 7–24. It is in ‘nature’ – hidden in the Dutch landscape – that Michelle finds ‘culture’, and photography becomes the means to remember that place-far-away. Photographing in the dark puts a light on it. At the river, we remember what we thought was forgotten. At the river, we are not alone.

You came to go, came to go far.

Came to go far [and] bring wood to the river.

But it takes a long time, it is far to the river.

Thank you, friends.The song texts for The untangled tales were compiled from Michiel van Kempen, Een geschiedenis van de Surinaamse literatuur (Paramaribo: Uitgeverij Okopipi, 2002); Melville Herskovits and Francis Herskovits, Suriname Folk-Lore (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936); and Jacques Arends, Language and Slavery: A Social and Linguistic History of the Suriname Creoles (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2017).

The river is far, and carrying wood takes time. For the second chapter of The untangled tales, Michelle moved her photographic enquiry to the river’s edge, the borderspace where water meets land. The verge bears witness to – or perhaps remembers – the colonial encounter of arrivals and departures. In the flash of the camera, the night river’s edge becomes a liminal space between dreaming and waking, between the unknown and known, between the imagined and the real. Like castoffs from the past haunting the present, flotsam and jetsam festoon the water’s edge.

At the riverbank we enter another world. What does it mean to welcome, and to be welcomed at the verge? What does it mean to heal the borders between the past and now, between longing and belonging? What does it mean to meet at the in-between? With a colonial history whose traces continue to shape contemporary encounters, meeting points at the brink between me and you, between now and then, between colonised and coloniser, are necessary for shared reflections to emerge.‘I refer to sites of encounter where we might be met by the world in return, where we might learn to listen and cultivate humility in the face of a world that exceeds us, a world that never receded to the background of human ascension.’ From Charlotte Du Cann and Bayo Akomolefe, ‘When the Bones of Our Ancestors Speak to Us: A Fugitive Conversation with Bayo Akomolafe’, resilience, 28 October 2021, https://www.resilience.org/sto....

Wait for me at the corner

Other cultural repertoires with deep Surinamese histories informed the first chapter of The untangled tales, which was first shown in 2020 and included in Michelle’s current solo show at Mino Art Gallery. Connected through textiles and storytelling, these embodied oral histories have shaped the Surinamese cultural imagination and patterned many urban landscapes. Most visible is the printed, folded, and starched angisa or headscarf – a one-metre-by-one-metre folded piece of cloth with a complex and rich lexicon of meanings and design iterations that can be traced back centuries. Actively remembered, re-worn and re-performed in the everyday, the angisa survives as both a cultural practice and a signifying artform.

The Surinamese angisa is a beautiful, colourful head creation folded out of a starched cloth or a traditional printed headscarf. The angisa harbours a wealth of stories, traditions, and wisdoms of life. It functioned as a means of communication during colonial rule.At the moment, the angisa is in the spotlight and there is international recognition for this Surinamese cultural heritage. In 2014, the koto and angisa were placed on the list of intangible cultural heritage items in the Netherlands and Suriname. Jane Stjeward-Schubert, https://www.theuntangledtales.....

'Angisa "Fight"'. From the series The untangled Tales.

Fashion reflects a politics of belonging. My own work – as a cofounder of the African Fashion Research Institute – has been shaped by an urgency to remember, rethink, and rewrite African fashion histories that speak of the many diverse ways of wearing, knowing, making, and styling often absent in fashion books, exhibitions, and imaginations.Established in 2019 with cofounder Lesiba Mabitsela. See https://afri.digital. This includes our recent exploration of folds and pleats and creases in fashion from the continent. We find folds in so many forms and shapes, across so many cultures. They carry meanings both significant and small. Folds are expressions of status, and stories of trade. At the same time, the fold is place to hold or to hide. It can expand or reduce. The fold can be something remembered or it must be continually remade. The fold becomes an archive of multiple dimensions, containing history, memory, culture, and language. Folds travel too, between continents and across time. They are embodied and emboldened with meanings that are often stored in repertoires outside of mainstream, so-called global fashion.Erica de Greef, Staging Our Own Decolonial Response: Global Fashioning Assembly 2022, 13 October 2022, https://rcdfashion.wordpress.c....

Wait for me at the corner. Let them talk. Trouble. Hidden in plain sight, these messages are conveyed through the carefully constructed folds in the angisa.For more details on these cultural objects and narratives, see https://www.tailorsandwearers..... The fold’s deftly articulated language underpins its survival as a material history, akin to oral histories and other repertoires manifested beyond archives, printed materials and museums. The living legacy of the angisa’s many iterations across generations, with meanings that have remained intact, illustrates the poetic power performed through a series of nuanced folds and shapes. The angisa as repertoire performs a fashioned and embodied memory.‘Many other kinds of knowledge that involved no written component were passed on through expressive culture – through dances, rituals, funerals, colors and majestic displays of power and wealth.’ From Diana Taylor, The Repertoire and the Archive: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2033), 17–18.

The repertoire supports the transmission of social knowledge, memory, and a sense of identity through creative performance.

Reclaiming and celebrating the angisa has informed a larger koto project, Tailors and Wearers, that Michelle founded together with Jane Stjeward-Schubert and Ella Broek in 2021. Reclamation informs the work of many fashion scholars working with and from the Global South, where creating replicas,Pierre-Antoine Vettorello’s exhibition Black Yarns, Goutte d’Or at Cité des Internationale, Paris, in March 2022 forms part of his larger project addressing Senegalese fashion stories that have been erased from history. See https://www.citedesartsparis.n.... recording oral histories, or examining archival photographs of African fashion practices can uncover erased narratives and contribute to new libraries of knowledge. The angisa performs as one of these libraries. The recently published Goma Weri (2022)Jane Stjeward-Schubert, Ella Broek, and Michelle Piergoelam, Goma Weri: Beleving en techniek van Afro-Surinaamse klederdracht (Edam: LM Publishers, 2023). co-produced by Jane, Ella and Michelle, and Keti Koti (2023)Janice Deul, Keti Koti (Amsterdam: Ambo|Anthos, 2023). by Janice Deul support these re-collections of cultural knowledges. The books, the patterns, and the photographs offer ways to remember that which is hard to find, lost, or undocumented.

'Nightview'. From the series Songs in a strange land, 2022.

Decolonial healing

Sensing into the darkness, Michelle’s photographs invite the viewer into a quieter – if not also disquieting – reception. They invite an intimate reckoning with the violence of historical micro-narratives. The photographs act as portals of a decolonial kind. The untangled tales invite a slower kind of engagement, of confronting the scars of the colonial project. At the same time, they require deep listening. They are vistas beyond modernity.I am indebted to Sandra Niessen for her support and to Rolando Vázquez for his decolonial work. See Rolando Vàzquez, Vistas of Modernity (Mondriaan Fund, 2020).

In many ways, Michelle’s photographs reveal less than they show. They are tiny glimpses of knowing, of seeing in the shadows. The lichen and leaves and limbs we furtively try to know quickly shape-shift, and backgrounds become fleeting moments of time, or traces of other moments of time. The untangled tales makes visible moments that are illegible to some, and legible to others. Photographing in the darkness refuses an easy reading.

But if we take time and listen to the silences and absences of history that are speaking their presences,Walter Mignolo, The Idea of Latin America (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 157. we may begin to remember that our (hi)stories are layered and shared. That the present is constantly interspersed by the past. And that decolonial healing is like a bridge in the night where the journey is not always clear.

Editor's note

Michelle Piergoelam (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) is an art photographer who creates visual stories based on cultural myths, dreams, and memories – images where cultural traditions, stories, and scenery are intertwined. She makes conscious use of native stories in order to spotlight their cultural importance, and as witness to culture and history. With her project The untangled tale, she was nominated for Blurring the Lines 2020 and the Kassel Dummy Award 2020, and received second prize in the Zilveren Camera Prize for Storytelling 2020. Her most recent book ’Songs In A Strange Land’ is one of the finalists of The Photobook Award from Encontros da Imagem (2023).

Her first international solo exhibition, featuring chapters one and two of The untangled tales, is on show from 12 May 2023 till 19 June 2023 at 2023 Mino Art Space in Antwerp.