Photo credits: Inge Meijer

On Inge Meijer’s A Garden Revisioned

Or on Claiming Space for an Ecology of Dissident Migrations

Editor’s note

During a three-month residency in 2019, Dutch artist Inge Meijer came across a massive archive of pre-wedding photography at a bankrupt wedding hall in Gwangju, South Korea. An artificial garden on the roof of the building had been used as a set for pre-wedding shoots. Meijer started working on the archive, which resulted in her ongoing installation project A Garden Revisioned. Trigger and FOTODOK (Utrecht, the Netherlands) invited curator and writer Natasha Christia to peer into the archival garden’s current state and also offer some context in terms of pandemic restrictions. This essay is the outcome of her dialogue with the artist as a keeper of the archive, and it recreates Christia’s personal (virtual) experiences of the situations, gaps and attempted relations that Meijer’s installation embodies. Christia delivers a toolbox of reflections addressed to both readers and the artist, for the garden continues to grow.

Natasha Christia

14 jun. 2021 • 18 min

'A maple tree is travelling on a trailer through a picturesque Dutch landscape of canals and lowland farms. The terrain is flat; the tree, disconnected from its soil, remains solemn in its dispossessed authority; a mute hostage tied in ropes, struggles against the wind, leans forward and backwards, drifts through different contexts towards an uncertain destination…'

From the writer’s notes on Maple Tree.

An economy of the incongruous migrations of natural elements, one that defies what’s normal and what’s not, resurfaces vehemently in the projects of Inge Meijer. In The Plant Collection,Inge Meijer, The Plant Collection (Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019). the Dutch artist retrieved from oblivion a group of thirty-nine exotic plants that, from 1939 to 1983, had thrived next to the exhibits of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. This group of non-native plant species, considered fit for brightening visits to the museum’s temporary exhibitions, had followed long-established colonial trade routes to reach its destination. In 2013, the museum retired the very last of these plants, and it found shelter at the home of a former employee. As with her Maple Tree – which I’ve chosen to describe, in an elliptic form, at the outset of this essay – Meijer contaminates history’s official narrative with the seemingly secondary and accidental fables of nature. When it comes to unearthing history’s inherent contradictions and frictions, the taxonomies of forgotten plants are significantly eloquent. Domesticated within the museum’s impassive visual records as silent and humorous security guards standing next to paintings by the likes of Mark Rothko, Piet Mondrian, and Christo, plants speak both to appreciation and control within a depository for imperial languages.

In A Garden Revisioned, her ongoing project and the main subject of this essay, Meijer takes her quest for unnoticed routine situations, involuntary migrations and incidental exchanges even further. Unlike her aforementioned projects, in which the thematic subjects were clearly illustrated through materially and conceptually sealed objects of optical contemplation, A Garden Revisited emerges as a spectral entity of practical philosophy – a work to be, travelling and shifting in context and space. Here, the process of enquiry and research radically takes on a central role. Not only does Meijer turn her full attention to the experience of accessing and relating to her materials – she also grants them a physical locus that enables her and others to experience, process and perform their ecologies of relations again and again.

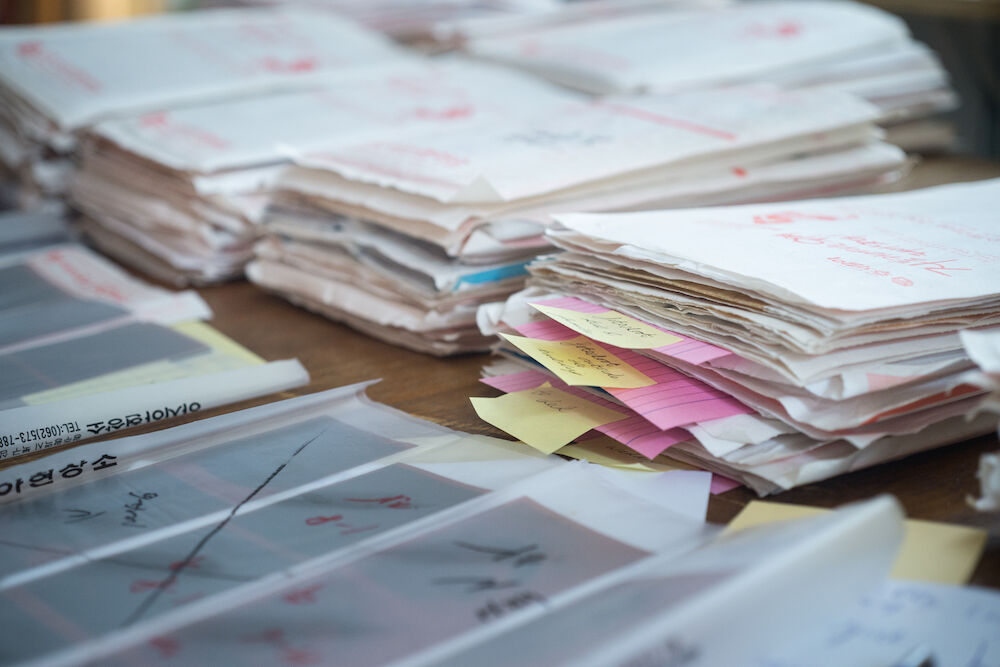

A Garden Revisioned’s moment of inception is as spectral as its content. In August 2019, Meijer landed in Gwangju, South Korea, for the start of a three-month residency. She arrived without any preconceived ideas of what she might explore. The view from the window of her residence was of an artificially wild garden on the rooftop of a neighbouring six-storey building. It turned out that between 1988 and 2006, the building, which was unoccupied at the time she saw it, had been the city’s largest wedding palace, hosting more than 200 weddings a day. The artificial garden had been used as a set for pre-wedding shoots, which were typically part of the marriage registration process. All throughout the wedding palace, couples could rent ceremonial clothing and props and visit beauty salons to prepare for photo shoots, which took place either indoors or up in the garden. Around the time of Meijer’s arrival, the vacant building had been recently purchased by an urban developer and was slated to be demolished and replaced with a new officetel complex. Over the course of her three-month sojourn in Gwangju, Meijer witnessed and documented its demolition. In the weeks prior to its commencement, she was able to access the defunct wedding hall’s vacant but intact interiors, and she retrieved the piles of contact sheets and negatives she found scattered across its floors.

As in many of her previous projects, here, too, was an unexpected encounter with a vanishing ecosystem: an ecosystem of images at stake, exemplified, in this case, by a precarious artificial garden. I like to think that Meijer was as intrigued as I am by the garden seen as a site for any activity geared to cultivation, design and care – the garden as a field of growth, decline and stagnation. The garden also reiterates the obsessive alignment of nature with the archival undercurrent of her work. As a field of human intervention and control, communion with nature stages societal, labour-based and commodity-informed power dynamics, but it also operates as an affective space of interconnections and acts of maintenance, enhancing a transformation that mediates the human and non-human worlds.

Meijer’s second visit to Gwangju was postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Back in Amsterdam, where she is based, she found herself working as the provisional custodian of an orphaned assemblage, which included more than 200 envelopes of negatives, VHS tapes, interviews and photographs of the wedding palace’s showroom. She had originally recollected the material without any fixed programmatic intention. So what to do with it now? How to negotiate her accidental ownership? How to engage with the presences and stories preserved in the assemblage? How to tackle her own unknowingness?

A Garden Revisioned was initially conceived as a mentally and physically relational public space for formulating and sharing these questions and problematics as well as for processing documentation gathered during Meijer’s first visit to South Korea.Inge Meijer, Lebohang Kganye, Marianne Ingleby and Pablo Lerma, Pass it On. Private Stories, Public Histories (Exhibition curated by Daria Tuminas, FOTODOK, Utrecht, The Netherlands, November 2020–February 2021). https://www.fotodok.org/en/exhibition-pass-it-on-private-stories-public-histories/

The exhibition is followed up by the publication [LINK TO COME] launching in summer 2021 The environment that frames it was recreated as a studio. It includes a large, light table with room for a dozen visitors along its perimeter on which sleeves filled with wedding-portrait negatives are laid out. Those are complemented by printer’s colour proofs, rolled up on the floor, which correspond to the basic categories identified during Meijer’s ongoing research process and printed at random. There are also three photographs of the palace’s showroom (the only portion of the gathered material that was originally destined for publication), framed and exhibited for the occasion. Finally, two stacked TVs play her video documentation of the building’s demolition (top) and the rooftop garden pre-demolition (bottom).

With the assistance of artist Alma Kim, Meijer planned to perform a series of research imperatives. For example: ‘digitise the film, systematise materials and prepare studies of the photographs’ elements’. At the same time, Meijer and her team were available for meetings and exchanges with the reduced groups of visitors who were allowed to enter the exhibition space. Due to the ongoing pandemic and related restrictions, the physical installation remained open for just three weeks in November 2020 – an important detail in its living, real-time curriculum. In early April 2021, access to it was provided through a virtual tour.

AN ARCHIVE THAT IS NOT

A Garden Revisioned is less about the ‘self-proclaimed’ archive Meijer has in her hands and more about the idea of an archive concerned with its form and unidirectional logic. The designation ‘an archive’ is assigned to a spectral image assemblage incidentally performing such an operation. By the term ‘image assemblage’, I refer less to the images themselves than to what they show and what we can make out of them. It’s about the accidental and usually overlooked relations we establish on a daily basis that are important when making sense of the world. It is ultimately about images seen as ‘maple trees’ migrating through different conditions and contexts, and it is also about the acknowledgment of a dissident ecology of volatile meanings inhabiting the process of digging, mowing and weeding any image assemblage.

The installation becomes the event of the work. It renders transparent a series of potential relations between the assemblage, its provisional guardian and the visitor or viewer. These relations dispute and jeopardise what lies at the core of the archival as defined by Jacques Derrida in Archive Fever: the principle of arche – understood as commencement (the point at which things commence) and commandment (the point at which gods and men create laws and command) – and the power of consignation (understood as domiciliation – and, I might add, domestication), which take place in lieu of archontic relations.Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’, Diacritics

vol. 25, no. 2 (Summer 1995), 9–63. Derrida uses the term ‘toponomology’ to refer to this combination of localisation and the law. He signifies the word ‘archive’ in terms of arkhē but also in terms of the Greek word arkheion. An arkheion is ‘initially a house, a domicile, and address, the residence of the superior magistrates, the archons, those who commanded’ (Derrida 1996, 2).

The physical space delineates the realm within and outside the work. As in any room, there are windows onto various worlds: the window onto the wedding palace’s demolition (see Meijer’s video works); the window onto its former existence (see the displayed negatives, colour proofs, framed prints and video of the still-standing garden); and the actual context of the involuntary migration of the material from South Korea to the Netherlands (the whole installation as an event). These states of flows are the punctum of A Garden Revisioned. They raise questions about how images and things involuntarily shift places and are taken hold of within various contexts – about how we look at images as well as how they look at us.

CREATING AN ACTIVE SPACE

Thus, instead of regarding the archive as an institution that preserves the past as though its contents do not directly impact us, I propose to see the archive as a shared place, define it as shared place that enables one to maintain the past incomplete, or to preserve what Benjamin referred to as the ‘incompleteness of the past’.

- Ariella AzoulayAriella Azoulay, ‘Archive’, Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon no. 1 (21 July 2017), http://www.politicalconcepts.org/archive-ariella-azoulay/.

A Garden Revisioned cannot be reduced to a sample-share inventory of information about South Korean wedding rituals, folkloric props and characters. The experience economy it produces engenders situations that invite outsiders of this taxonomy (the viewers) to transgress it, to become intimate with it and to empathise with it. This goes to the core of the archival. The right to share becomes a claim to disturb the symbolic order at large, to ask its sovereignty various multidirectional questions, among them, to paraphrase Ariella Azoulay,Azoulay, ‘Archive’. In Azoulay’s words: ‘Instead of asking “What is an archive?”, then, in a way that leaves the archive outside and retains it as a fortress outside our world, making us its pilgrims, I shall first ask “Why an archive?”, or “What do we look for in an archive?”, and only then answer what an archive is’. why am I here and what do I look for?

How, then, to relate to an unknown heritage without applying, even if unintentionally, a colonialist reading and assumptions of Western supremacy? How to tackle, as Derrida acutely frames it, ‘The violence of this communal dissymmetry [which] remains at once extraordinary and, precisely, most common…happening each time we address someone, each time we call them while supposing, that is to say while imposing a “we”, and thus while inscribing the other person in this situation of an at once spectral and patriarchic nursling’?Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever’, 30.

Meijer is aware that entering these rocky areas implies a radical questioning of ownership of the material. She underlines her right to feel uncomfortable with this assumption and to replace it with the idea of care. Caring as an action – as imposing care on somebody or something – is no less problematic, since it may also revolve around dynamics of oppression. But to gaze with care, to act with care – that is something entirely different. It is holding oneself accountable to these questions and the complex dynamics behind them.

Found negatives at deserted marriage location in Gwanju, South-Korea. Photo by Joeri Boelhouwer

It is no coincidence that the visual materials featured in the installation are impersonal and low-key fragments of a spectral whole. In this sample of material about wedding photography, you will not see a single face because black dots cover the faces of everyone in the reproductions of the original negatives. Distributed in a random order by the printer’s software, the displayed sheets include provisional studies tagged by the artist as ‘gesture I’, ‘gesture II’, ‘feet positions’, ‘fabrics’, ‘covering’ and ‘holding’. When it comes to taking advantage of photo booth gems, Meijer’s overall approach complicates and problematises the temptation to exoticise the vernacular. It goes against the easy tendency of framing it as a set of reductive aestheticised representations that fit our boxes and preconceived ideas and fulfil our voyeuristic penchant for the folkloric.

Gazing with care implies the allowance of an open, affective space that contemplates complex relations, agencies and accountabilities within and outside the work. That brings me to one of the pillars of Meijer’s practice: ‘The will to connect what cannot be connected’, a quote I have appropriated from Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn. Hirschhorn is known for his interventions in public space. His ‘Direct Sculptures’, ‘Altars’, ‘Kiosks’ and ‘Monuments’ (dedicated to Gilles Deleuze, Georges Bataille and Antonio Gramsci) operate as momentary, active and counter-hegemonic spaces of engaged discussion.Hal Foster, ‘An Archival Impulse’, October 110 (Fall 2004), 9. The diverse ecosystem of encounters and relations such works reinforce – as well as their transformative commitments – make me think of A Garden Revisited. The will to connect what can’t be connected embraces a philosophy of gaps – the willingness to pay attention to insignificant things and actions in between. I refer to the cracked space of our existence. To the fleetingness, fragility and ungraspable knowledge to be encountered in apparently banal situations, such as those in Maple Tree, that perforate pretensions about what has been valued, what has been passed on and what has been passed over.

I WANT TO ASK YOU A QUESTION TOO

Viewed as a part of this broader relational philosophy, Meijer’s overall practice embodies the effort to make sense of a world that is, in many senses, ungraspable. It allows us all, irrespective of role – fellow artists, the intentional or accidental visitor(s) and, above all, Meijer herself, as the artist (the one who is supposedly instructive) – to perform all possible scenarios of putting the bits and pieces together. It allows for the right to reflect, learn, unlearn and collapse already established positions and roles. On entering the space, no one expects us to be right or wrong, to agree or disagree. There is no need to be interactive or reactive. The only condition is to be active, here understood as supporting the activity of thinking.I borrowed these ideas from Thomas Hirschhorn: ‘I do not want to do an interactive work. I want to do an active work. To me, the most important activity that an art work can provoke is the activity of thinking. Andy Warhol’s Big Electric Chair (1967) makes me think, but it is a painting on a museum wall. An active work requires that I first give of myself’(Claire Bishop, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’, October 110 [Fall 2004], 65).

In her thought-provoking indecisiveness with the assemblage of visual documents she handles, Meijer defies today’s general tendency to rest too comfortably in an ideal of immanent togetherness. Her impassive associative impetus when it comes to integrating these materials into the space is also a way of critiquing notions of the archive as ‘a form of Western subjectivity and a changing set of powerful institutional practices’Iain Chambers, Giulia Grechi and Mark Nash, ‘Voices in the Ruins’, The Ruined Archive, eds. Iain Chambers, Giulia Grechi and Mark Nash, MELA Books 11 (Milan: Politecnico di Milano, 2014). http://www.mela-project.polimi.it/upl/cms/attach/20140722/102611541_7245.pdf. that has been indiscriminately used both by colonisers and the colonised, perpetuating an imperial reading of the world. Her marked sensations of unease and discomfort towards any story constructed with a fixed resolution – to be used as a vehicle for ingeminating a certain source of authority and reliability – sustains a tension among viewers, participants and contexts. ‘How can we talk about narratives when things are incomplete?’ she asks. She describes her position as being closer to that of ‘some negatives that originate from a certain place, and probably, in a moment in time, I will make it an incomplete archive about a moment about a building that does not exist anymore and yet it still exists in memories of people.… There is so much we transmit without being part of the Archive’From a conversation with the artist, 22 February 2021..

In an era of intractable polarisation and universal truth advocacy, one that seems to daily reconfirm Hannah Arendt’s assertion that the security of ideological trenches has replaced political thinking,‘The danger in exchanging the necessary insecurity of philosophical thought for the total explanation of an ideology and its Weltanschauung is not even so much the risk of falling for some usually vulgar, always uncritical assumption as of exchanging the freedom inherent in man’s capacity to think for the straitjacket of logic with which man can force himself almost as violently as he is forced by some outside power’ (Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism [New York: Meridian, 1962], 470). claiming space for the ambivalence of our individual existences and combating the fear of self-contradiction is crucial. A Garden Revisioned – in the way it is now and will continue to evolve – potentiates a space in which to rehearse dialogue, vulnerability and intellectual investment from a position of care. It is ultimately about creating bridges, about giving oneself to conversations or voluntary silences shared with others. The loose, anonymous and elliptic experience economy of its content, in a space where nothing appears to happen, presupposes the viewer as a subject of independent thought rather than a member of a herd. In this sense, Meijer’s approach evokes, however remotely, Hirschhorn’s political and emancipatory strategies, for she chooses ‘materials that do not intimidate, a format that doesn’t dominate, a device that does not seduce’Full quotation: ‘To make art politically means to choose materials that do not intimidate, a format that doesn’t dominate, a device that does not seduce. To make art politically is not to submit to an ideology or to denounce the system, in opposition to so-called “political art”’ (Thomas Hirschhorn in conversation with Okwui Enwezor, in Thomas Hirschhorn: Jumbo Spoons and Big Cake [Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2000], 27)., but nonetheless disrupt and disperse the established classificatory modus operandi of visual knowledge.

A Garden Revisioned, screenshot from virtual tour of Pass It On. Private Stories Public Histories (nov 2020 – Feb 2021), Fotodok, Utrecht

POSTSCRIPT

On my laptop screen in Barcelona, approximately 1,210 kilometers from Utrecht in the Netherlands, I browse Meijer’s room. The pandemic has prevented me from visiting the installation in person, but distance isn’t an issue. I feel complicit in this provisional owning. I find myself in front of a stack of two mute TVs. On the upper screen, the camera follows the wedding palace’s demolition from a distance; on the lower, the rooftop garden, filmed up close, still reigns in its last days. These two temporalities mark the inconsistent rhythm of things in our multitasked, routine lives. While the huge excavator climbs up an artificial hill of rubble to tear the building down, the garden remains in the lower frame: untouched, peaceful, idyllic. All of a sudden, I find myself recalling one of my recent readings: 'Ruining the archive means unmasking the bad conscience, the authoritarian function of social and cultural control and construction…exhibiting and concealing—in sum the way in which it institutes and naturalises a whole regime of memorability: what is to be remembered in the future, and how it is to be remembered'.

In A Garden Revisioned, reducing something to ruins is equivalent to denaturalising (or even desacralising) a systemic process of interpretation while being incessantly confronted with proximity and distance, ownership and the public realm. It is also time dissolving. Resistant to closure, the soil of the Garden will have to be ploughed every week, for the angles and the questions will’ve changed. At this stage, neither you, I, or Meijer herself can predict how it will all evolve. Will it continue to take a physical form as an interactive public studio, recompensing the frustration of its truncated first staging in Utrecht? Will Meijer eventually return to Gwangju to continue her field research? What will the other artists contribute? Will they be accomplices or adversaries?

All possible scenarios for the Garden are open. It may grow into a publication, it may grow into a second space, it may entangle its savage roots with the remembrance of marriages and other attempts for relationships. Or it may do something else entirely. All options are workable as long as their potentialities remain focused on reactivating a space of reencounter with this visual ecosystem of cut-out portraits of anonymous brides and grooms leaning towards the camera, their eyes covered with black dots, their destinations and destinies uncertain. In this tension generated by the conflicting and the disparate, the untranslated and the untranslatable, we see ourselves. I see myself. It is 22:37, the world is a mess and we are a part of it.I am indebted to Inge Meijer for ‘bringing herself to the conversation’ we had about the project and her overall practice back on 22 February 2021 and to the curator of the exhibition, Daria Tuminas, for her additional insight into the nature of their collaboration.