Still, Je crois qu'il y a une confusion chez vous. Vous croyez que moi je veux vous imiter. #FatimaMernissi, 2017

© Saddie Choua, Courtesy of the artist

Not (Safe) at Home

On Being Present in the Work of Saddie Choua

In spring 2015, Dirk Snauwaert, the director of WIELS in Brussels, encouraged me to linger at the centre a bit longer to see the work of Saddie Choua, who was presenting the outcome of her residency at WIELS. I’d just visited Body Talk, an exhibition of the work of six female African artists. I later wrote a review entitled ‘Die White Man’, playfully referring to Die Wit Man, a work by South African artist Tracey Rose showcased in the exhibition.Petra Van Brabandt, ‘Sterf Witte Man’, Rekto:Verso, no. 66 (2015). http://18.197.1.103/artikel/sterf-witte-man. Today, I realise how my metaphoric call to overthrow white patriarchy still centres it. As cognitive linguist and philosopher George Lakoff pointed out in Don’t Think of an Elephant, one should instead shift the metaphors and reset the frames.George Lakoff, Don’t Think of an Elephant (Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2014).

Petra Van Brabandt

11 feb. 2021 • 15 min

The artist was present, and I cautiously entered her exhibition room.In what follows, I won’t abide to the pro forma distancing use of the last name as is custom in writing. Saddie Choua is a close friend and our friendship is that (im)possible and painful journey of creating sisterhood while constantly forgetting and reminding each other of that what unites and separates us. The personal is political, and therefore I’ll use the first name in accordance with the intimacy of friendship that it implies. I’d always preferred to be alone with artwork, as my impostor syndrome reached a peak in the company of artists (no doubt, mine was an ordinary case of class anxiety). I’d internalised the modernist frame of the genius avant-garde artist who, in my magnifying imagination, was no less than the embodiment of Michel Foucault’s Parrhesia

[T]he parrhesiastes is someone who takes a risk.… More precisely, parrhesia is a verbal activity in which a speaker expresses his [sic] personal relationship to truth, and risks his [sic] life because he [sic] recognizes truth-telling as a duty to improve or help other people (as well as himself [sic]).Michel Foucault, Fearless Speech (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001), 15-20.

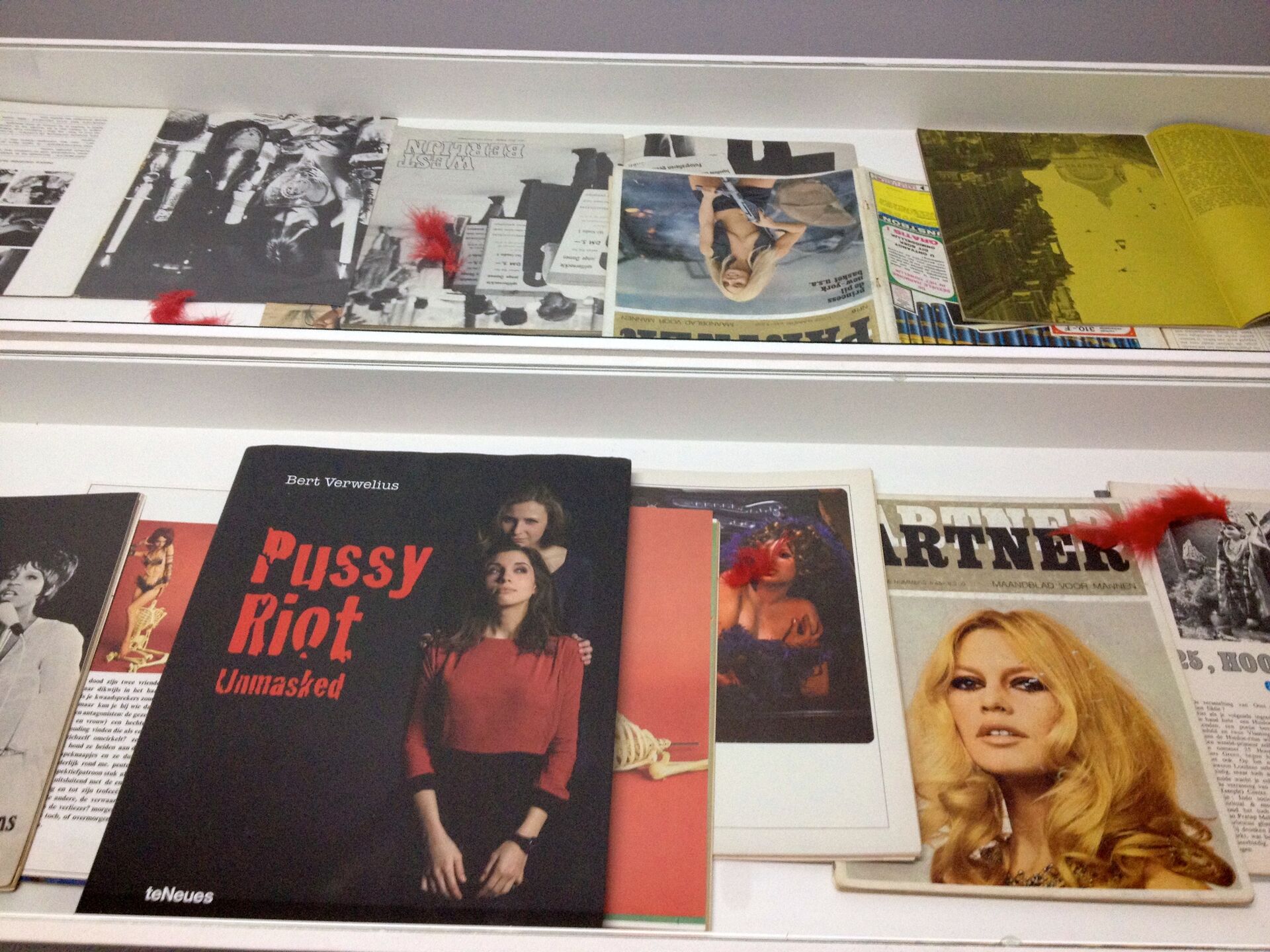

In my memory, Saddie’s room is dark, the only light emitting from projections and small screens. I remember seeing life-sized images of running horses and suffragette Emily Davison in free fall.Saddie Choua, I’m Sorry I can’t offer you tea, my hands are a little tight, 2014, multi-screen. I remember a painfully funny Mohammed Ali on the metaphoric use of ‘white’ and ‘black’.At a later stage, this resulted in Saddie Choua, We All Love Muhammad Ali, 2016, video/installation. And I remember the eerily attractive covers of Partner, Louis Paul Boon’s magazine series for men.Saddie Choua, Sexism-o-thèque, 2015-ongoing. I have no idea if these memories are correct or filled in with later encounters with her work, but what’s beyond a doubt is that I was like a ball in a pinball machine. My gaze darted in all directions, bedazzled by familiar images and objects, exalted that someone had considered them worthy of selection and attention. I was overwhelmed by the intertextual friendships and alliances the artist had constructed – and how forcefully they appealed to me. There were feminist aesthetics of class, gender and race at work that wasn’t the result of blasé artistic appropriation. I immediately felt there was something dangerously and painfully at stake: myself. Inadvertently, I’d stumbled into a maze that expressed the artist’s personal and poignant relation to truth, not as a verbal activity but through the creation of uncommon relations between images – and not as an imposed narrative order but as incessant efforts to reset the frame.

Every subsequent meeting with Saddie’s work has sparked this somaesthetical excitement. The encounter is first of all emotional, not cognitive. The visual landscape of her installations and videos, which always carries traces of her presence and resuscitates the cultural archive of class, gender and race, is deeply triggering. It incites the urge to relate. This relation is self-reflective and relentlessly uncomfortable; it reveals the pitfalls of double consciousness, the processes of self-betrayal (class betrayal, gender betrayal) and the racial injustices in which I’m involved. The impact is epistemological; it affects my relation to knowledge about the world and my place in it and invariably leads to a process of political-subjective becoming.

Through a combination of found footage, personal archives and objects, filming and relational events, the artist expresses her personal truth regarding her being the object of racial, gender and class oppression and the subject of feminist resistance. Through autobiographical signs and clues, Saddie is present in her work; she can’t afford to be otherwise. Oppression, which consists of symbolic and factual erasure, forces her to occupy an insisting and abrasive presence. This presence isn’t joyful, wilful or rewarding; it’s ‘being present where you wish to disappear.’I take this expression from an article by Nana Adusei-Poku, ‘On Being Present Where You Wish to Disappear’, e-flux Journal, no. 80 (2017). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/80/101727/on-being-present-where-you-wish-to-disappear/

This resisting presence testifies that it isn’t only the personal that’s political; rather, the political is also personal. The collective trauma of structural oppression is personally experienced in body and mind. The artist’s presence is a signifier for this personal experience of oppression, including the traumatising fight against it. It’s a weapon against abstraction and erasure. In this sense, the resisting presence of the artist – in family pictures, home videos, performances and relational art events; in personal objects, books and records; in family migration stories and colonial histories; in images of revisited landscapes and places – is an incessant reminder of the erasure and framing of the female migrant artist in the predominantly white art world. The artist can’t be absent because she can’t give in to the erasure of working-class, racialised women. As history won’t give her leave, she can’t and won’t give us leave either: the presence of the traumatised body and voice makes the incessant erasure forcibly visible.

In 2010, Saddie started her ongoing soap series The Chouas. Starting from an old photo of her father with his four brothers, the project is an ongoing collection of works in which the artist explores diasporic self-portraits, spectres of colonial history and alienation caused by migration. The Chouas isn’t an effort at storytelling but a creation of contexts that enable the artist to regain control over images and image-making. Or at least, it’s the construction of lab situations in which the artist explores the above.

In the 2016 The Chouas #Episode3 I swear by God Almighty, I say the truth and nothing but the truth, Saddie uses voice-over to share her search for other images. By ‘other’, she means images that defy not only the dominant gaze upon her but also how she’s forced to look at herself. The most revolting aspect of oppression is the resulting double consciousness that takes root in the body of the oppressed; they don’t only experience their oppression but also come to see themselves through the eyes of their oppressors.See W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Boston: Bedford Books, 1997 (1903)) and Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 1967 (1952)). The most tragic aspect of this oppressive gaze is that it legitimises the oppression; the way the ‘other’ is seen is a historical construction that legitimises and justifies her oppression. This gaze grows as a second skin, as an imprisoning frame. The fear is that the artist becomes doomed to the frame and doesn’t succeed in creating other images. ‘Can I shift the metaphors and reset the frames?’ is one of the core questions of The Chouas episodes. Can I throw off this double consciousness and break the oppressor’s othering and, thus, the legitimacy of his oppression?

Saddie’s work has moved further and further from storytelling in general let alone that of her own story in particular. Humanist documentary only aggravates her predicament. The endless production of humanising stories about the other, including the empathetic ‘speaking-nearby’ the other or ‘giving voice’ to the other, more often than not reaffirms the existing dominant frames. Who’s in the position to give voice? ‘Je crois qu'il y a une confusion chez vous. Vous croyez que moi je veux vous imiter.’ #FatimaMernissi, a brilliant editing of several interview fragments with the renowned sociologist Fatima Mernissi, reveals how even Mernissi, when being invited to tell her story, was invariably subjected to the dominant frame. Each time she ‘got voice’ from a white man, she had to reclaim the floor. ‘You think I want to imitate you!’ she exasperatedly exclaimed to a German interlocutor. However, with her unrelenting eye for class dynamics, Saddie exposes that Mernissi’s success in resetting the frame was entirely dependent on the social status of the men involved.

Saddie’s work is anti-documentary. It reveals the racist and sexist frames of all cultural discourses and images, including humanist documentary. Her goal is to reveal these frames using confrontational or repetitive editing, association and juxtaposition. In The Chouas #Episode3, she quotes the Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour, who called for the abandonment of the harmonising yet totalising linear narrative; in none of her works does Saddie submit to the linear, harmonious and frameable story of the other (herself). The challenge is to tilt and reset the frame; the risk is getting caught up in the internalised and dominant one. Double consciousness is an unjust condition, and hers is an unsafe position.

The strength of Saddie’s work lies in its specific aesthetics of an unfamiliar familiar. Her working material is fiction and non-fiction, autobiographical and historical, found footage and her own filming, literature and soaps, music videos and film, and objects. She selects fragments and gives them special attention – a music video by Sister Sledge, a photo of Frank Zappa, an excerpt of Tchekov’s Cherry Orchard, a YouTube video of a strike at a Citroën factory, a home video of little Saddie dancing, a carpet she bought in Morocco, her pain killers and plants and on and on it goes. She sources from and relies on the spectator’s zapping culture and intertextual habits; the recognisability and fragmentism produce in the spectator excitement and pleasure. But then she makes a second move; hers isn’t an ironic postmodern gesture. She upgrades her fragments to the status of being worthy of consideration and reconsideration; she meticulously assembles them as carrying value and meaning and, more so, as clues not to be missed, not so much in what they show but rather in how they show.

Saddie constructs her parrheissiastic practice through careful selection and association. The fragments she chooses are on the one hand highly recognisable – yet, on the other, they’re utterly unfamiliar. It’s precisely this twofoldedness of her images that evokes an emotional urge to engage with them. You emotionally relate to what you’re seeing because of its familiarity, yet at the same time, you’re led into its most unfamiliar corners. This strangeness resides partly in the specific parts of the fragments Saddie selects but even more so in the surprising way she brings everything together, thus creating the effect of an unfamiliar familiar.

In 2016’s We All Love Muhammad Ali, the image of boxer Muhammad Ali produces sparks of celebrity enthusiasm in the viewer. White viewers, however, are less familiar with his anti-racist struggle and here get confronted with it without warning or concession. Viewers of colour will experience a different kind of unfamiliarity. The racist frames of popular celebrity culture are all too familiar to them, and Saddie’s different framing of Ali’s sharp and blunt speech evokes a painfully uncommon recognisability.

In 2017’s The Chouas #Episode5 Am I the only one who is like me?, we encounter the famous and beloved actress Meryl Streep; an initial sympathy emerges in our bodies but is swiftly swept away by her racist utterances. When this is subsequently combined with footage from Out of Africa, we experience a chilling reframing of our gaze. All of a sudden, the racism embedded in these images can’t be denied, and their auratic spell is shattered. This is uncomfortable by design; Saddie’s reframing turns the mirror to our own racism as proven by our previous blindness to the common racist frame of Hollywood cinema.

These are only a few examples of how her artwork makes us visually halt and stutter. In The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading, Edmund Burke Huey explained how we hardly see what we read; our consciousness ‘throws us forward’ and fills in the gaps based on repeated previous experiences.Edmund Burke Huey, The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1968 (1908)). Saddie’s video installations throw us backward; she lays out the familiar pieces but invites us to link the dots in ways we never tried before. We rub our eyes and look again. We falter and hesitate.

What distinguishes Saddie’s intertextual practice from an ironic gesture is her aesthetics of care. She pays careful attention to the cultural archive – to visual culture, popular culture and histories. She focuses on fragments that are at best regarded as amusing or funny, commonly reduced to their surface. By giving them her attention, these fragments become valuable, significant and telling. The artist is the guardian against oblivion; her fragments are prevented from sinking into the sea of anecdotes and cheap sentimentality. Saddie doesn’t allow us to be sentimentally touched by the young and innocent Shirley Temple dancing with Bill Robinson; she subtitles it with fragments of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.I refer to the video installation The Chouas #Episode5 Am I The Only One Who Is Like Me?, 2018. From the endless flow of insignificant amusing documents, she fishes up fragments that appear deadly serious once on land. By spreading them out together, she reveals their encompassing violent frame.

The historical legacy of the feminist, working-class and anti-racist struggle is another thread in her care aesthetics. Her portrait of Mernissi doesn’t recount the life story of the great Moroccan sociologist; she remembers the meaning of her work by projecting it into the future. And as Mernissi has always put women at the centre of her work, Saddie in turn integrates homages to other women in her portrait of Mernissi, including the spoken word artist Samira Saleh, who performs a poem, and a fragment of 1985’s Oscar-winning A Greek Tragedy by forgotten Belgian filmmaker Nicole Van Goethem. She cherishes Louis Paul Boon and his Partner magazines, criticising his sexism, orientalism and exoticism in her Sexism-o-thèque all the while holding him close as a working-class hero. In The Chouas #Episode5, she chooses to remember a long-forgotten strike in a French Citroën plant during which French and migrant workers stood shoulder to shoulder. In so doing, she’s keeping the socialist struggle warm for a time when we’ve overcome divisive racism. And she remembers Chantal Akerman and Jeanne Dielman, alongside Ousmane Sembène and Diouana, playing uncomfortably with the idea of whether Akerman could’ve watched Sembène’s film a little too closely – could she have overlooked Sembène?I refer to the video installation Today is the Shortest Day of the Year But Somehow Hanging Around With You All Day Makes it Seem Like the Longest, Perverse Decolonisation, Akademie der Künste der Welt, Cologne,

2018. Saddie’s editing, which pays homage to Akerman and Sembène and even more so to the fictional-non-fictional characters of Jeanne Dielman and Diouana, is also one of the most revealing, art-critical close readings in art. Her loving care comes with razor-sharp criticism or, as philosopher Georges Yancy would call it, her love is a gift of loss.Georges Yancy, ‘Dear White America’, The New York Times (New York City, New York), 24 December 2015. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/12/24/dear-white-america/

In her latest work, Saddie radicalises this aesthetics of care in salons and relational events. She seems to be more at ease in the art world. She takes up more space and occupies exclusive spaces. She finds ways to bring care and comfort to the real and present and to herself and others. In 2018’s Fatima’s Salon and 2018–2019’s Take Care of Yourself and Walk - Lamb Chops Should Not Be Overcooked, she strengthens herself with her books and records, with familiar objects, cosy chairs and painkillers. She invites people to accompany her and adds plants in need of care and attention but who generously return oxygen and shade. In Mechelen, she took the audience on a walk alongside comforting and violent places, the medicinal herbal garden of Dodoens on the one hand and the headquarters of the Flemish far right party Vlaams Belang on the other. Even in front of this last one’s door, she managed to create a caring interjection, reading anti-fascist poems of Saïda Menebhi with her companions. She ended the walk with a plentiful picnic in the park with food she’d carefully and lovingly prepared. In the gallery, however, she integrated in her Take Care of Yourself salon a painful reminder of the surrounding violence; a video of Yma Sumac leaving a stage because she thought the audience was making fun of her. Whether the audience’s intentions were indeed mean isn’t at stake here, nor is the proportionality of her reaction; what the clip shows is how the frame of trauma caused by racism is all encompassing, inescapable and unjust.

Saddie’s work isn’t speaking nearby; it’s a practice of listening nearby.‘Speaking nearby’ is how filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha describes her practice. See Nancy N. Chen, ‘ “Speaking Nearby”: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha’, Visual Anthropology Review 8, no. 1, 82-91. She closely listens to the cultural archive, historical legacies, comforting objects and herself. As such, she develops an extreme sensitivity to being unsafe at home. Her work shows that the care that society hasn’t provided will never be replaced by one’s own efforts. The comforting spaces are still unsafe.

In several of her works, Saddie integrates scenes she filmed into found footage. These parts are highly symbolic; their pace is slow and meditative. They function in the complexity of the video installations as bridges to reflection. They make the spectator aware of the false consciousness that’s always threatening from the horizon, for the artist as well as the viewer, and that’s a lure into forgetfulness and depoliticisation. These bridges are an invitation to an uneasy solidarity, raising your awareness of your place in gender, racial and class power relations and functioning as an invitation to repoliticise.

The encounter with Saddie’s work was and continues to be life changing to me. Its epistemological radicality makes it difficult to write about it in the same way it’s difficult to write about a love story while navigating the turbulence of its experience. Timothy Morton wrote ‘Art is causal. That’s what’s frightening about it.’This is my misinterpretation of Timothy Morton, ‘Charisma and Causality’, ArtReview, (November 2015). https://artreview.com/november... In my experience, however, such an epistemological and emotional intrusion of art in life is uncommon. Contrary to what I used to believe; artists only rarely speak personal truths to power. In the legacy of modern aesthetics, from Immanuel Kant to Clive Bell and on until today, one is rather invited to climb ‘the cold, white peaks of art.’Clive Bell, Art (London: Grey Arrow, 1961 [1914]), 42. Saddie’s work affords no such disinterested pleasure; it pulls you in her parrhesiastic practice, and as she isn’t comfortably at home, you won’t be either.