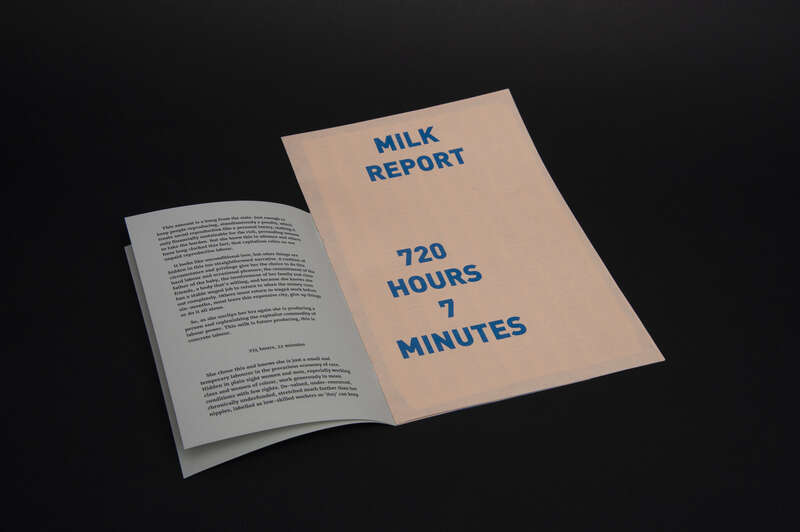

Milk Report by Conway and Young, printed publication, 26 x 18 cm 2019 courtesy of the artist and Birth Rites Collection

Motherhood, dignity, and care in productive work

This essay won’t be about my work. Though it depends on what you regard as ‘work’.

My most recent work, called Postcards from Home (2020 to present), involves domestic care practices. My goal is to increase awareness of the socio/political impact of care daily routines and to open a dialogue around it. The outcome – yet to be complete – is a collection of postcards, a visual survey authored by participants, showing objects used to perform care. My interest in domestic practices developed in conjunction with my own experience of maternity.

Being a mother not only influenced my practice, it made me reflect more on the paradox between (economical) value and domestic work in a success-driven society. Care being dominantly framed as mainly feminine and maternal, causes reproductive work to fall outside of the sphere (or ‘canon’) of production.

Griselda Pollock’s work is crucial if one wants to understand the tensions between the canon and maternity. I supplement my re-reading of Pollock’s Differencing the Canon (1999), with the work of the economist Mariana Mazzucato and the Marxist-feminist theorist Silvia Federici. This essay, as a letter from a daughter of capitalism, hopes to insert caring into a renewed, developing narrative about economics through the work of these three women.

Dafne Salis

03 mrt. 2022 • 27 min

The first time I got pregnant, I was 22 and with the wrong guy. I booked a voluntary interruption of pregnancy,Italian Law permits abortion within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy, but hospitals book the procedure around a month or more from your call. as I didn’t want to lose the chance of terminating it if I wanted to. A month was long enough to decide that I would’ve regretted not having the child even if the conditions were unfavourable, and I made an appointment for my first scan.

The fetus was dead. At around the ninth week, his heart had stopped. My womb refused to let him go, and there were no external signs that the pregnancy was no longer viable. The day after the scan, I had a curettage to safeguard future pregnancies. Although the gynecologist reassured me of my ability to have children in the future. I mourned the embryo, felt envious of other mothers, and took some time to recover from the loss. At the same time, I was grateful not to be sharing parenthood with that guy.

Nine years later, my husband and I wanted to become parents. I was pregnant again. I fearfully had another scan and asked the gynecologist what to do to keep the fetus alive. She told me I could do nothing to help the pregnancy along. It would either develop or not, independent of my actions.

‘You cannot do anything to help the pregnancy reach full term.’

After the scan, I spent a long hour in the bathroom, where I looked at myself in the mirror and thought, ‘There’s nothing I can do to assure this pregnancy will end with a baby. The outcome is out of my hands. I can only take care of myself, because if the pregnancy continues, I’ll then be nurturing the baby in the best way I can.’

As a daughter of capitalism, I’ve been encouraged to be active – productive with my hands and brain.That is, having been born in 1984 in Rome, in a European country, with white skin, and from a bourgeois family.My experience of pregnancy was a shift away from everything I’d been taught to do and think to that point. How can I be productive by just taking care? To become a parent, I had to observe and act with love and tenderness. How is that productive? How does it lead to a child? How is it possible to generate a life while escaping the logic of production? Why am I not used to thinking about taking care, nurturing, and walking with when thinking about production? Where is the maternal narrative in neoliberal economies? Is economic production a cultural construct? Is there a maternal narrative in the current construction of economic value, or do its canons reify masculine narcissism?

The impossibility of guaranteeing a birth, together with the responsibility to act in the baby’s best interest, brought me to a paradox. To make a baby, I couldn’t do anything, but I was compelled to take care of the pregnancy to preserve it and ensure its health. I wasn’t used to not having control of the immediate consequences of my actions.In terms of education and parenting, the relation between cause and effect is more capricious. I wasn’t used to taking care of myself, let alone taking care of myself beyond myself. But from that moment in the bathroom, I started to care, until I hugged my final product in my arms. Since then, taking care of has been a non-stop, all-encompassing, 24/7 job.

The mind shift I experienced during pregnancy and birth, nurturing and parenting – together with the hard work I perform every day – makes me wonder why care doesn’t receive economic recognition in the same way production does. I’m not at all suggesting that a human life has economic value in any way similar to a good produced in the free markets of capital. Rather, my question is why we assign economic value to the action of producing goods (not just physical objects but also services for consumers and businesses) while we assign caring almost none, despite the human effort put into both and the immense benefit nurturing and taking care of each other has for the whole of society.

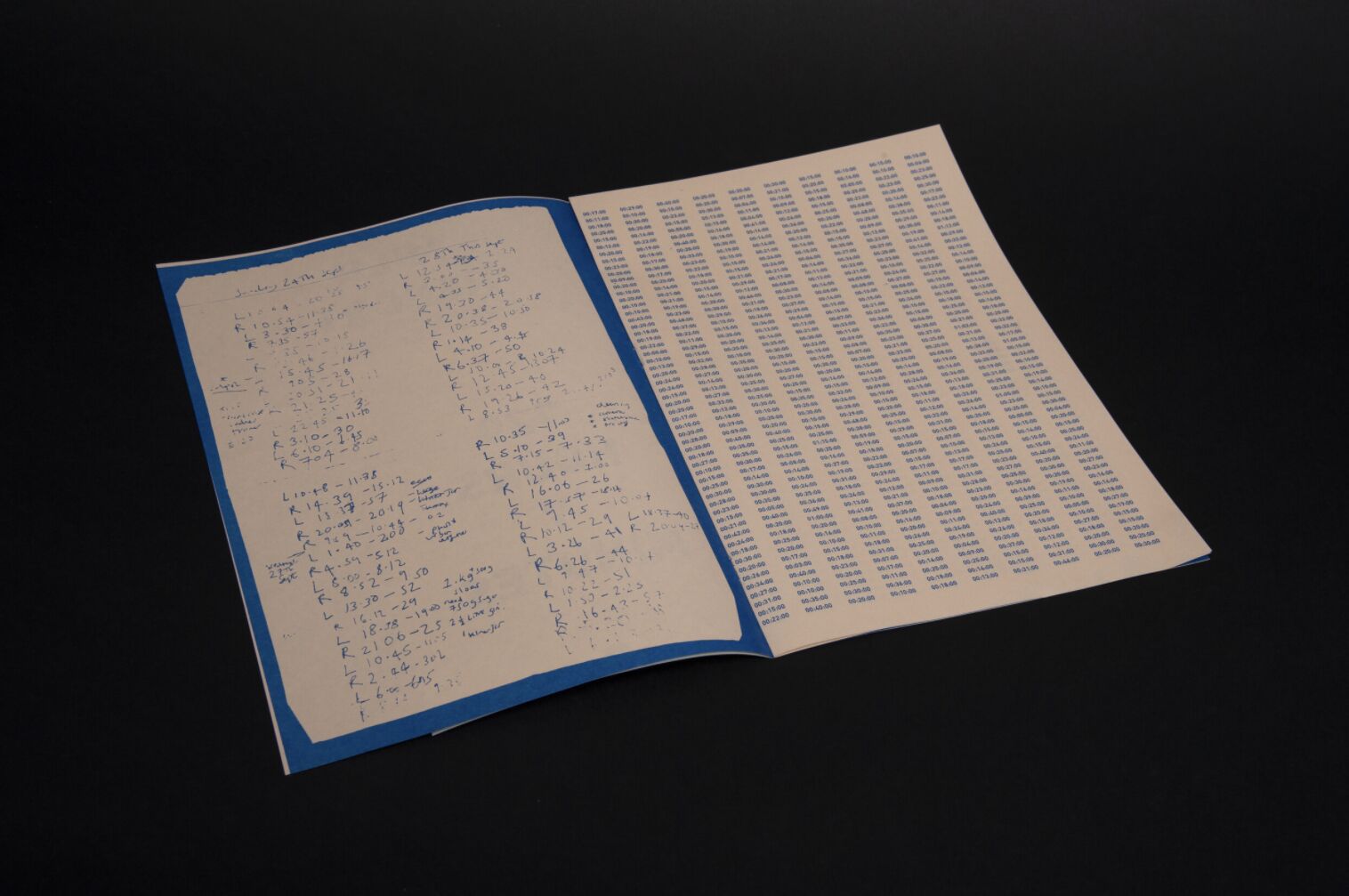

Milk Report is a print piece recording the hours and minutes Young spent breastfeeding during the first six- months after giving birth. This totalled 720 hours and 7 minutes. This data is accompanied by a narrative text exploring the politics of care through the lense of breastfeeding. Seeking full remuneration for the labour-intensive work undertaken, based on the 2019 National Living Wage of £8.21 per hour, an edition of 720 copies of Milk Report have been printed to be sold for £8.21 each. This will equate to a wage of £5916.95 once all of the Milk Reports are sold. http://www.conwayandyoung.com

Economists sustaining capitalism have a rather clear – although unsatisfactory – response to this paradox: there’s no market where people can pay for parental love, and given the nature of sentiments underlying the interaction between adults and children or relatives, such relationships cannot be formally stated in private contracts.

Historically, our paradigm has been to grow the quantity of consumption. To create monetary value, one must generate goods to sell. The difference between the expenses involved in generating the goods and the earnings derived from their selling determines the economic value of the transaction – with little or no regard for the quality of the objects produced, nor the quality of their production, nor its sustainability, nor the conditions of workers. No matter how valuable a human activity is, if no market for it exists, it will be underestimated and undervalued by a capitalist society shaped by the commitment to endless economic growth.The explanation of capitalist markets was nicely provided by Dr. Livio Romano, industrial economist at Confindustria and adjunct professor at Luiss Guido Carli. Living in a capitalist neoliberal society can convince us that this explanation about economic value is sensible, but I wonder: is there a canon underpinning narratives of production, of economic value?

Griselda Pollock’s differencing the canon

I have been a mother for six years now. The experience of parenting changed my life not only on a practical level but also in my understanding of the world. The figure of the mother caught my attention, especially how the maternal intersects with (or is denied in) other areas of our lives.

The work of Griselda Pollock is bound up with maternity. Her analysis revisits art history, looking for the reasons for women's exclusion from it. Pollock turns her attention towards masculine and paternal discursive structures as concurrently responsible for underpinning female participation, along with more traditional interpretations of men’s social and political power.‘2020 Holberg Prize and Nils Klim Prize Laureates Announced’, holbergprisen, 5 March 2020, https://holbergprisen.no/en/ne...; For this article, I chose to look at Pollock’s work not only because her ideas won her the 2020 Holberg Prize – the equivalent of the Nobel prize in the arts and humanities – and I think they deserve to be known, spread, and discussed, but also because her points are far from being resolved.In a recent interview, commenting on the Drents Museum’s exhibition Viva la Frida! (October 2021–March 2022, Drents Museum, Assen, the Netherlands) by painter and artist Frida Kahlo, Pollock noticed that the exhibition was mostly focused on the biography of the artist rather than her work, therefore denying her innovative contribution to the political and artistic field. Anna Van Leeuwen, De Morgen, 16/10/2021, Historica Griselda Pollock: ‘De kunstgeschiedenis klopt van geen kanten’, accessed 23 Nov 2021.[https://www.demorgen.be/tv-cultuur/historica-griselda-pollock-de-kunstgeschiedenis-klopt-van-geen-kanten~b0985193/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.be%2F]

This essay finds its theoretical roots in Pollock’s ground-breaking Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art's Histories (1999).I find this book somewhat problematic because it proceeds on the basis of representation and difference between the masculine and feminine. My recent reading has upset some of the principles on which the argument depends: the feminine/masculine dichotomy, the expectation/demand for differencing, and the problematization of the term ‘representation’. Although the premises are problematic, I find that the push towards an inclusion of differentiation is valid and that a problematization of the canon through sexual difference is necessary. Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art's Histories (Taylor & Francis Group, 1999). In this book, Pollock questions art history through an inquiry into its canons. The book is divided into three parts. The first, entitled ‘Firing the Canon’, analyses how feminists have engaged with the dominant culture in order to subvert it. The second section is dedicated to the work of canonical art, looking for traces of the maternal. In the third section, entitled ‘Heroines’, the author shares her scepticism about women artists inserted into the traditional – male – canon. In the fourth, concluding section, Pollock offers a reading of work by Black women artists as a way of introducing elements of differentiation and challenging the current all-white, male canon.

I’d like to dwell on the first section of Pollock’s book on ‘art history canons’. The latter is defined as the rule of what is deemed important, and so containing what must remain of art’s narratives and practices. Tradition is the natural face of the canon because it’s always a selection of what was there already, and the exclusions it makes are obscured.See, for example, Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), p. 115 and Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art's Histories (Taylor & Francis Group, 1999). The initial critique of the canon came from those who were voiceless, who were not included in the canon – who have been stereotyped, discriminated against, and oppressed by it. Just by looking at who’s included and who’s not, it becomes clear that the canon reinforces the presence of the white male, mimicking a patrilineal heritage.

Pollock identifies three strategies to counteract the existing canon. Two have already been adopted by feminist artists while the last one is the one introduced by the art historian. Since the critique of the canon started over the opposition between who’s in and who’s out, the first two strategies involve expanding the canon, either to the currently excluded bodies (women, for example) or to the concepts forming them. Expanding the canon to those who were traditionally excluded carries the risk that the structure of masculine culture will only be confirmed and corroborated by those new additions, thus hiding the profound reasons for and inner workings of the exclusion. The expansion of the canon, rather than focusing on bodies, might look at integrating a maternal genealogy, but this option, even if might enlarge the scope of the canon, reintroduces the discourses of the in/out/other and reinforces the dichotomy between who is dominant and who is shut out. The third strategy suggested by Pollock is to abolish the canon altogether. To do so, Pollock asserts that we need to enact a differencing of the canon, wherein the gerund form of the verb is used to indicate that the process of differentiation is non-definitive and in continuous evolution. This solution not only seems more appropriate, as it doesn’t reintroduce power relationships, but it also facilitates a welcoming of polylogues. In this case, the cultural field must be reimagined as a space for ‘multiple occupancy for the differencing’.Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art's Histories (Taylor & Francis Group, 1999), p.11.

Domestic Propaganda, 2020 – on going @Dafne Salis

A series of embroideries against the presumption of heteronormativity, using the language and the reproduction system of flowers. The embroideries are sewn on fabrics for domestic use and given as gifts for regular use in the house: cot bedsheets set, table cloth.

To criticize the canon while introducing a polylogue, Pollock looks at the Freudian concept of the father-hero’s male desires and Barthes’ idea of myth. To use psychoanalysis in feminist theory is risky, as it has already been proven to be limited because it does not take into account historical inscriptions like race and class. Nevertheless, Pollock considers it appropriate here, since her analysis’s point of departure is exactly ‘this position of apparent alterity’Ibidem, p.8; the exclusion is constructed starting from the opposition woman/man, a simplistic binary pair which summons the positions of in and out. In other words, the distinction – the alterity between men and women – is built exactly to sustain men’s power; otherwise there’s no reason to insist on their different positions. Condensed in the figures of man/father and woman/mother/other, the perspective of the mother is therefore taken on board as a starting point and a tool to dismantle this ‘apparent alterity’.

What would introduce an alternative to the ‘apparent alterity’ is to analyse the role of desire in the formation of the canon. Pollock argues that the existing canon excludes not so much women as political/social bodies but rather ‘femininity’s pleasures and resources as a possible and expanded way of relating to and representing the world.’Ibidem, p.8 Her purpose is to introduce feminist and feminine desire into the readings of the already acknowledged history of art. For Pollock, the difficulty of abandoning the current canon depends largely on the profound investments of its defenders and the pleasures they gain from it. Looking through Freud’s perspective, art histories have a link to the infantile stage of the idealisation of the father, followed by rivalry and disappointment, which might be compensated by another fantasy opposing the father: the hero-artist. From this perspective, the canon becomes an expression of masculine narcissism, and the history of art a narcissistic identification with the artist as myth-hero-father. The construction of the myth is read through Barthes’ lens.Roland Barthes, ‘Myth Today’, in Mythologies, [1957], trans. Annette Lavers (London: Paladin Books, 1973). ‘What the world supplies to myth is a historical reality, defined ... by the way in which men have produced or used it; and what myth gives in return is a natural image of this reality.’ Ibid., p. 142. The semiologist describes it as an instrument to undermine politicized discourses by transforming them into nature. A mythological erasure of time and political viewpoints likewise erases the possibility of challenging them. Introducing differences into the canon, into the mythological narration of art history, means reintroducing political discourse into it and mining its deep structures.

Differencing economic value

Just as art history can be read as an expression of patriarchal narcissism, can economic value be seen as an expression of the same drive? In a similar vein to Pollock’s idea that art canons are historically constituted by and embody a masculine desire to identify with the artist-hero-father, might it be possible to expose economic narratives as embodiments of the same desires? Are economic standards a form of masculine narcissism based on patrilinear genealogy? If we expose economic discourses as permeated with sexual difference, would it be possible to recognize masculine and paternal desires within them? Why is care not included within the category of economic value?

In her book The Value of Everything (2017), the economist Mariana Mazzucato questions the narratives surrounding economics. In the introduction, she notes that in nearly forty years, between 1975 and 2017, wages in the United States have stayed the same, if not fallen, while GPD has tripled and production has grown by sixty percent. She observes that during this span, a tiny elite has earned the excess. Considering that the neoliberal narrative maintains that wages are assigned according to earnings from production, and that whoever produces more is rewarded suitably, are the elite the real producers, or is the narrative constructed to justify the unequal distribution of profits and the concentration of wealth in an elite owner class? Following this introduction, Mazzucato argues that economic value is based mainly on narratives, derived from what we consciously or unconsciously assign value to. In the light of this grounding of economics in narratives, is it possible to analyse economic structures in a way akin to Pollock’s treatment of art history? Can we analyse value in terms of desires and pleasures? Is it possible to expose neoliberal economics as narcissistic masculine identification?

I don’t have the competencies in economics to be in a position to provide rigorous answers or the kind of analysis Pollock gave to art history, but I would like to try thinking about caring and producing outside the structures I was born within.Challenging existing interpretations of the world is how I feed my visual language and photographic production. I look for an emancipation of already existing structures, and new interpretations originated by my experience as human being. And I would like to expose how deeply the paternal is linked to economic/valuable production, as opposed to the maternal, unpayable kind of production.

Pollock identifies sexual difference as a useful tool in maintaining structures of power. She argues that when feminism recognizes that sexual difference influences the aesthetic representation of women at a very deep level, it also recognizes men as sexualized subjects, thus stripping them of their universality, and it becomes possible to acknowledge the canon as gendered discourse. The canon becomes visible as an enunciation of power. The feminist interruption of naturalized (hetero)sexual difference makes evident that the canon exists purely to sustain sexual difference, which positions white men (and their power) on one side and everyone else on the other.

Production versus care?

To start, I compared definitions and synonyms of the verbs ‘to care’, ‘to produce’, and ‘to work’, analysing how ‘to produce’ intersects mother/father. This task, at first glance pedantic and superfluous, serves to inquire about the prejudices and constructs of a language that I perceive as objective but is rather one way tradition and power perpetuate themselves. For the purposes of comparison, I consulted three online dictionaries.Google Dictionary, www.thesaurus.com, and Cambridge Dictionary I won’t include the listings in full but will limit myself to some observations.

The first regards the entry ‘to produce’. It’s possible to sense an implicit polarity related to a mother/father dichotomy, which becomes more explicit if we look at synonyms.Google Dictionary, www.thesaurus.com and Merriam-Webster websites.‘To produce’ is associated with making, generating, and initiating, and implies the active participation of the subject. In cases where ‘to produce’ means initiating, contributing to, determining, or being responsible for, the synonyms include ‘to father’ – for example, ‘he fathered the improvement plan’ or ‘he is the father of modern science’. Conversely, ‘to produce’ can be linked to the verb ‘to mother’, but in this case it only refers to biological happenings like generating, fostering, breeding, nurturing, or giving birth. ‘To mother’ and ‘to produce’ do not meet on the level of responsibility or of generating ideas: one does not say ‘to mother an idea’. The link between ‘to produce’ and ‘to mother’ exists only in the subcategory of nurturing, breeding, and giving birth.

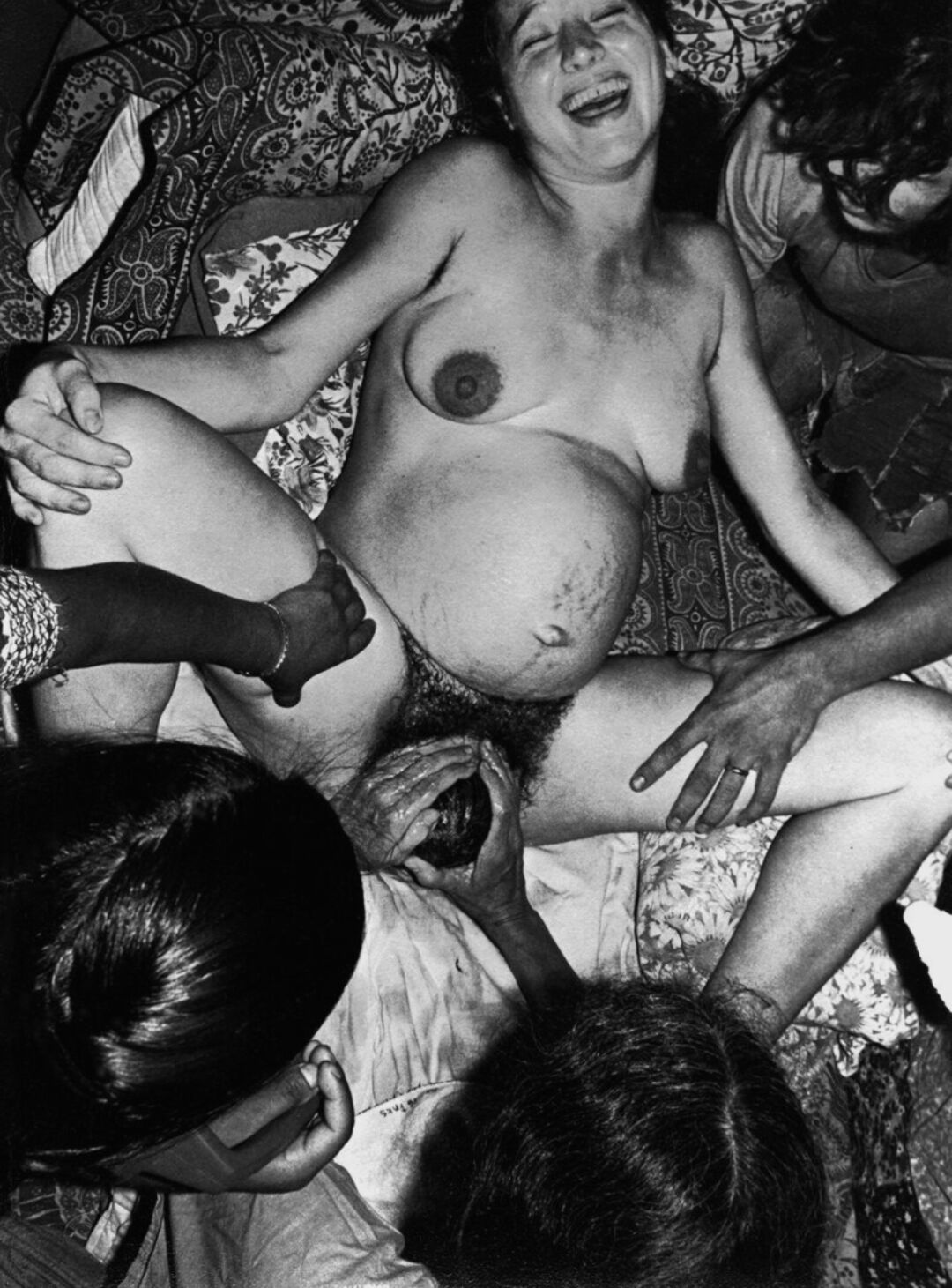

Hermione Wiltshire, Therese in Ecstatic Childbirth, 2008, courtesy of the artist and Birth Rites Collection

Once we confront the different connotations of ‘to father’ and ‘to mother’ as they relate to production, we see that the set of meanings linked to the word ‘to mother’ are included only partially inside the meanings conveyed by ‘to produce’, making it a subset of the latter used in specific contexts. We also see that these specific contexts are in the private sphere. Even in the language, ‘to produce’ and ‘to father’ meet in the action of creating something that has an impact on the world, while production in the maternal sense does not escape the private, intimate realm of the house. This confinement to the private immediately decreases the importance of maternal production for collective gain.

The restriction of maternal production to the private realm, referring to breeding, nurturing, and giving birth, can be illustrated by a story of a photograph by Hermione Wiltshire. The picture portrays a woman giving birth, with the head of baby crowning. It was taken by a nurse during labour and later appropriated by Wiltshire, whose intention was to challenge the representation of birth. It was hanged in the labour ward of King’s College Hospital in London as part of the Birth Rites Collection, a permanent fixture in the hospital. It was soon removed on the grounds of offensiveness: a picture of a woman giving birth in the labour ward is offensive. Female production – as in giving birth – cannot enter the public space of a hospital’s labour ward. It must be kept private, unseen. Politics of care are kept obscured from the political realm, and given their link to the maternal, they are easily dismissed from society, as if the personal were only private, and I wonder, given the premises, how can we recognize care as essential for collective gain.

In wondering if the strategy of breaking existing paradigms can be applied to economics, can we recognize economic production as pleasing the masculine and the paternal in the cultural and biological fields as well? Can we say that, biologically, capitalist production retraces, in the narrative of its enactment, what the father does to procreate? A strenuous investment at the beginning (conception) and, regardless of what happens in the meantime (pregnancy), the collection of products at the end. Biologically, the narrative speaks of fathers making an initial effort during conception and then harvesting the child from mother’s hands (possibly already grown and ready to work). The capitalist economy is also based on an initial investment followed by the harvesting and selling of products, mimicking the way we speak the father’s contribution to conceiving a child. What’s missing in capitalist production is the traditionally maternal input – the one that would take into consideration, during production, the quality of the product, the long-term sustainability of the process, the emotional and physical well-being of all parties – in other words, the care. Capitalism doesn’t look out for sustainability, nor for the quality of what it produces; it only asks for monetization at the end.

In a Harvard Business Review article by Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy, titled ‘GDP Is Not a Measure of Human Well-Being’ (2019), we read that economic studies and institutions have already started putting forward the limits of the descriptors of the economic growth. Since its definition by John Maynard Keynes in 1940, GDP is the tool, the device to measure economic growth of a country, over which social and political choices of governments are made. The definition was born during war time, while Keynes worked in the UK Treasury. He was looking for a measure to estimate what could be produced by Britain with the available resources.

But a measure created to assess wartime production capabilities of a nation has obvious drawbacks in peacetime. For one, GDP is by definition an aggregate measure that includes the value of goods and services produced in an economy over a certain period of time. There is no scope for the positive or negative effects created in the process of production and development. For example, GDP takes a positive count of the cars we produce but does not account for the emissions they generate; it adds the value of the sugar-laced beverages we sell but fails to subtract the health problems they cause; it includes the value of building new cities but does not discount for the vital forests they replace. As Robert Kennedy put it in his famous election speech in 1968, ‘it [GDP] measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.’Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy, GDP Is Not a Measure of Human Well-Being, Harvard Business Review, 04/10/2019, accessed 24/11/2021 [https://hbr.org/2019/10/gdp-is-not-a-measure-of-human-well-being]

Exposed Mother, 2021 @Dafne Salis

Exposed Mother is a photographic action about my experience of being a mother of young children. The skin is the photographic surface over which the sun impresses my sons’ presence, making manifests the playful and endurable relationships our mutual bodies intertwine.

Conversely, care is maternal and echoes in narration what the mother must undertake to have a child: it means inhabiting shared space, oxygen, water, food, and intimate connection through the placenta. The interdependency of the child with the mother is palpable. To care is to observe, to acknowledge vulnerability, to respond to biological and emotional needs, to think of connectionsElena Pulcini, Tra cura e giustizia. Le passioni come risorsa sociale (Bollati Boringhieri, 2020).; it is a relationality, an interdependency. It goes beyond the familiar cause and effect dynamic because the relationality goes both ways, and because it admits other subjects intervening in the action. So as a mother, I do not retain all the power and control over my son. The cause and effect relationship is spread out over time: it is not a given but becomes a possibility, and, for this reason, it lacks control and efficiency. Care is rather an attitude towards life, a mode of living. Yet it is constituted by practical actions every day, continuous over time.

Is there a way to insert care in the concept of production – without, of course, demeaning care in the logic of production? I have no answer to this question, nor will I attempt one.

In the cultural field, are economic discourses somehow favouring the paternal?I’m sorry this question takes the shape of a rhetorical one. Culturally, the modern era pushed fathers to produce, to provide economically for their children, while mothers were compelled to be at home, nursing children and caring for the house, the family, the elderly, and the sick. With the gradual recognition of women’s rights, work environments became progressively more open to women.Since each country has its own history and pace, I inevitably have to summarize them like I did. Though nowadays women and men are formally allowed to perform any job, discrimination continues to produce gender gaps in both leadership positions and wages.

To relegate women to performing unpaid duties, has devalued every task traditionally performed by women and relegated women to chores and other ‘lower’ forms of work. Personal reproductive labour is not in the slightest sense recognized as a job. Even institutionalized care jobs pay increasingly lower wages than in the past, and during the pandemic, nurses and doctors cared for our loved ones in ways that far exceeded their institutional requirements. They were celebrated as heroes but did not receive adequate compensation.For an example, I refer here to the 2019 protests by teachers and technicians in universities in England, and cuts to schools and health systems in England and Italy before the pandemic. Newspaper sources: Robert Booth, Care workers in England leaving for Amazon and other better-paid jobs, The Guardian, 4/09/2021, accessed 24/11/2021[https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/sep/04/care-workers-in-england-leaving-for-amazon-and-other-better-paid-jobs] Eric Berger, ‘I can’t do this anymore’: US faces nurse shortage from burnout, The Guardian, 19/11/202, accessed 24/11/2021 [https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/nov/19/us-faces-nurse-shortage-burnout-covid] Anonymous, I’m an NHS doctor – and I’ve had enough of people clapping for me, The Guardian, 21/05/2020. accessed 24/11/2021[https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/may/21/nhs-doctor-enough-people-clapping] Rachel Clarke, Now we health workers know how empty Boris Johnson’s ‘clap for heroes’ really was. The Guardian, 05/03/2021, accessed 24/11/2021 [https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/mar/05/boris-johnson-clap-patients-pay-offer] Affari Italiani, Infermieri Eroi? Anche dopo il Covid, vengono sottopagati e sono troppo pochi. 11/11/2020. Accessed 24/11/2021 [https://www.affaritaliani.it/medicina/infermieri-eroi-anche-dopo-il-covid-vengono-sottopagati-sono-troppo-pochi-766735.html] Annalisa Camilli, Da eroi a untori, il problema dell’Italia con gli infermieri, Internazionale 19/11/2020. Accessed 24/11/2021 https://www.internazionale.it/reportage/annalisa-camilli/2020/11/19/infermieri-italia-covid-coronavirus]

What would happen if we were to admit that the dichotomy between care and production, and the way we dignify the latter but not the former with economic investment, is a consequence of the narrative of the sexual difference? Or that what we assign value to in a capitalist society sustains patrilineal inheritance? Would it be possible to insert caring into a renewed, developing narrative about economics?

Domestic care as a real asset, or wages for housework revisited

I would like to imagine what the consequences of bringing care into the fold of value-making and economics could be.

The first consequence would be an inclusion of bodies within the labour market. By this, I mean that if we were to recognize domestic care tasks – reproductive labour – with a wage, people already performing it (mostly female-identifying individuals) will be automatically inserted into the job market. In her analysis, Mazzucato mentions domestic housework and offers an example: if a cleaner is hired by a man, she will receive a wage, health insurance, and pension contributions, and her work will be taken into account in the calculation of gross national income.I am reporting the gendered division of labour that Mazzucato discusses in her book on p. 101. If the same person doing the same housework marries the man, she loses her wage and the associated benefits. Moreover, her work no longer counts in national statistics, even though she delivers the same outcome. Paying wages to housewives would allow them to exit the black market. Moreover, it could affect the salary gender gap and increase wages for professionals performing care jobs.

To those who might argue that paying women for housework would increase the gender pay gap by removing the incentive to look for more professional roles, Silvia Federici replies in her essay 'Wages against Housework' (1975) that in being paid, women would automatically enter the workforce: they would have an income and economic independence, and they might be motivated to apply for other, better-paid positions. Moreover, it might help to gain better wages or regular salaries for those mostly Black or Brown women in richer countries who work as housekeepers. In this case, including care within the category of production would have the consequence of bringing more individuals in the economic fold.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development conceived by the United Nations in 2015 with the goal of correcting the deficiencies of the GDP as a tool for economic measurement includes a section on domestic care. One of the aims of the agenda is ‘to recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate.’United Nations’ Sustainable Development Agenda 2030. Goal 5.4, published on the UN website. https://www.un.org/sustainable... Although the goal of valuing care jobs is much appreciated, how can the UN assert the value of something in a world dominated by money if we still won’t spend a penny on it? Public services, infrastructure, and social protection policies, though needed, are not enough to give proper value to domestic work: it requires solid recognition through economic compensation.

Asking for money to perform care would mean allowing care to enter the current canon, but for someone wanting to exit this narrative, it’s a paradox. Just as Pollock regards the encounter between feminism and the canon as contradictory but necessary, I find it unavoidable to assign economic value to care in order to dismantle current narratives. Paying domestic jobs would allow us to realign, to redistribute current producers’ money, and to create a communal experience of caring for each other by tangibly recognizing and thanking those who perform them. Moreover, paying wages to housewives would destabilize capitalism, subtract free manpower, enhance the sense of community (given the work of care), and reduce household waste.

Moreover, as noted extensively already, reproductive work has been traditionally associated with women. This identification stems not only from a division of labour within the social structure – that is, men work in these sectors, women in these other sectors – but also from the fact that love and femininity are closely linked. Again, drawing on Federici’s work, in order to identify with other heterosexual women, women were expected to marry and serve their husbands and children in the house. The work was compensated by the supposed satisfaction of enacting the essence of womanhood: to offer love and to sacrifice oneself. Even in 2021, to suggest that caring for loved ones should be paid raises questions about love and affection.

In conclusion, if we show how sexual difference is present as a tool to exercise patrilinear power, is there an opportunity to reintroduce care as a dignified, valuable (and thus payable) contribution to society? Can we link production to fatherhood, through narratives connected with paternal and narcissistic desire? When we assess who is gaining the most from economic discourses, we see that men maintain the power in the economy and the pleasures coming from it. While fathers/men were culturally valued and paid based on work performed outside the home, women/mothers, with their roles inside the home, were left out of this valuation.

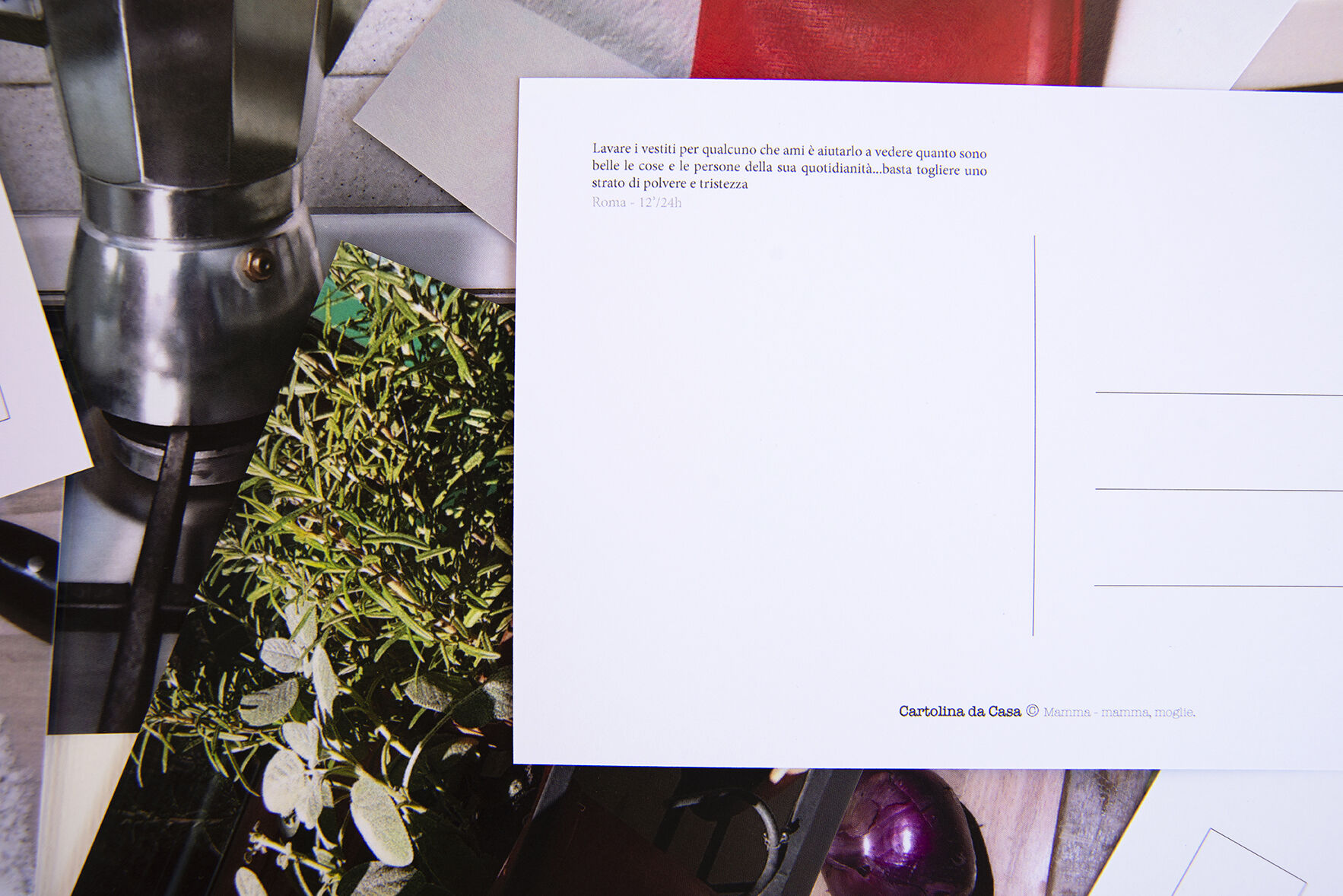

Cartoline da Casa, 2021 @Dafne Salis

Following Pollock’s scheme, I’m advocating for rethinking production (the type capitalism deems valuable through wages) as made possible by both paternal and maternal inputs, including care, caring, and taking care – care as both a job that creates valuable results and as a way of producing. And I hope to raise awareness about care by giving it a visual form through the survey I’m undertaking. Cartoline da Casa is an attempt to photographically represent care. Giving visibility to how people perceive domestic care and live it on a day-to-day basis seemed to me a good point to start. The questions raised in this text about care and the attempt to think about it, rather than being explicatory, are meant to lead to more questions and contribute to the existing dialogue.

Selected reading:

Barthes, Roland. ‘Myth Today’, in Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers. (London: Paladin Books, 1973).

Federici, Silvia. ‘Wages Against Housework’ (1975) in Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction and Feminist Struggle. (Oakland: PM Press, 2012).

Mazzucato, Mariana. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy. (London: Penguin Books, 2018).

Pollock, Griselda. Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art’s Histories. (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis GroupRoutledge, 1999).

Pulcini, Elena. Tra Cura e Giustizia. Le Passioni Come Risorsa Sociale. (Bollati Boringhierii, 2020).

Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977).