Hiền Hoàng, Scent from Heaven (2022–ongoing)

Still from the performance, performed by Moe Gotoda, camera by Rika Malottke, costume by Sanja Philipp, photo by Antine Yvez. Directed and produced by Hiền Hoàng. Courtesy of the artist.

Modes of Spirituality

Hiền Hoàng,Sebastian Koudijzer,Yvette Monahan,Léonard Pongo

18 apr. 2024 • 14 min

EDITOR'S NOTE. This contribution brings together art practices by Yvette Monahan, Hiền Hoàng, Sebastian Koudijzer, and Léonard Pongo – all dealing with different modes of spirituality in photography. It is part of the printed issue, Trigger #5: Energy and is now re:designed for this online publication.

Each editor of the issue invited one artist to respond to three questions in their own way: How would you define spirituality through your work? What kind of myths, traditions, or cosmologies are you invoking? What is ‘energy’ to you?

Spiritual energy, seemingly immaterial and hard to grasp, nevertheless has its physical manifestations in the world. Objects and rituals, traditions and oral narratives, bodily expressions of both human and non-human beings – all shape the surrounding reality. The increased interest in spirituality by contemporary makers working with the photographic medium is very telling. Might it be the urgency to unlearn and relearn what we know about ourselves and the planet, and how we know it? Some softer, non-extractive, humble, deep ways of knowing might emerge in this artistic search – and isn’t that what we need the most?

The modes of spirituality presented lay bare some of these potential pathways for knowledge to arise. For Monahan, it is about the need to address intuition and transcendence. For Hoàng, it is about reconsidering the relationship between cultural heritage and contemporary art. For Koudijzer, it is through a connection with ancestors – by commemorating and memorialising those who have been silenced by colonialism and its legacies - and by reflecting on one’s own identity. For Pongo, whose recent work transforms the rainforest into a spiritual actor, it is through respect for other-than-human presences in nature and the revival of Indigenous memory and cosmogony.

Spirituality here seems to have a connection with ‘repair’ – repairing wounds, repairing intrahuman or more-than-human connections, or even repairing nature. These contributions work together as a proposition for healing, unlearning energy, and becoming through energy.

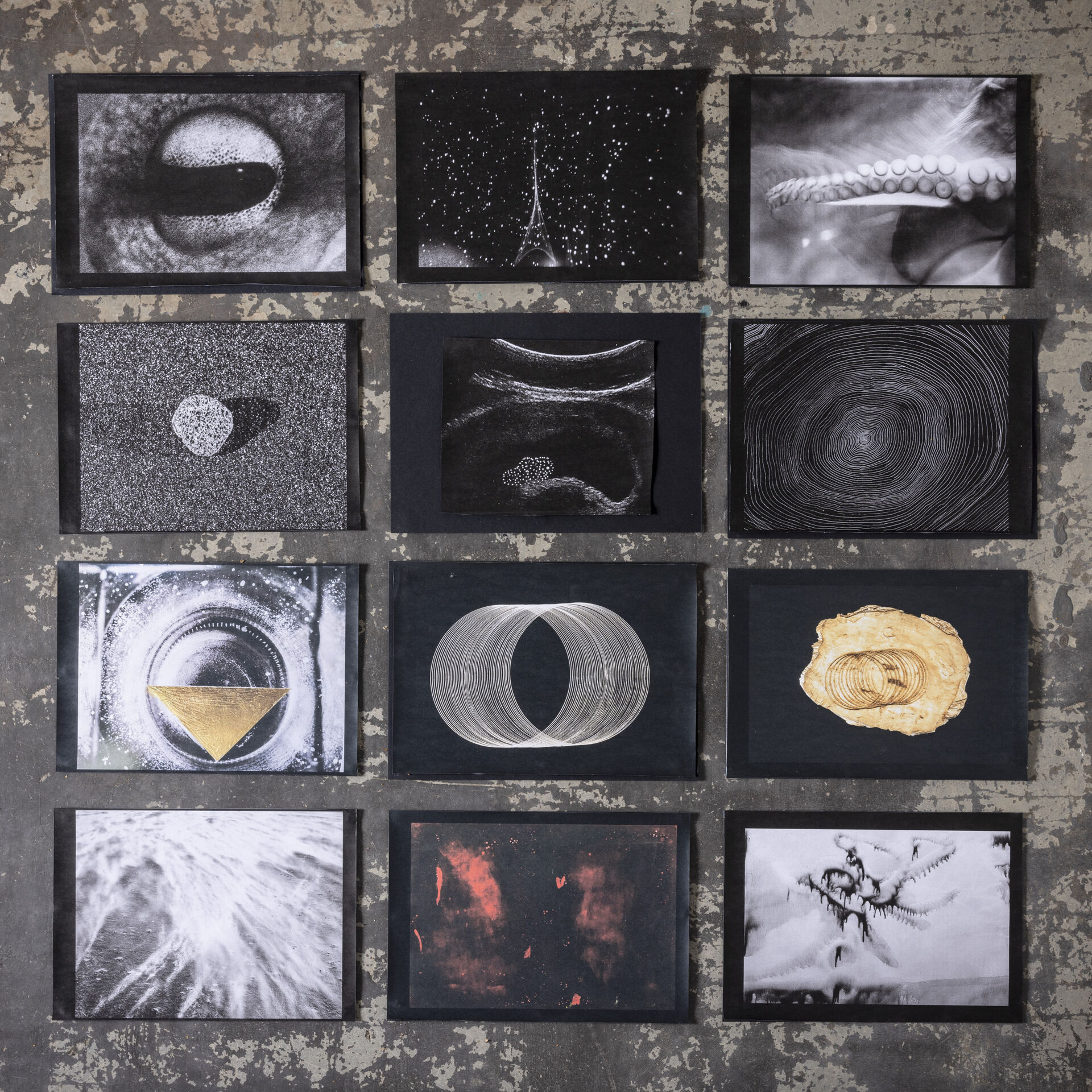

Loose leaf pages from the book dummy This unending story by Yvette Monahan

Yvette Monahan

This unending story explores resonance and consciousness through space, soundwaves, ancestry, and octopuses. The birth of my daughter was the cosmic catalyst that prompted research into the oscillating forces from small and large moments of creation. I sought to spiral inward to understand this transcendent experience while looking to art, science, and mythology to seek assurance. I wanted to hear from others who had used invisible forces and wild imagination to access their inner minds and outer spaces.

The etymology of photography summons something shamanic, from the Greek ‘drawing or writing with light’.Stephen Bull, Photography (Routledge, 2010), 5. It suggests harnessing natural forces, like bottling the wind or cradling the ocean. The late American photographer Minor White (1908- 1976) considered the photograph more than a document but ‘an index of invisible forces’,Aperture 237 (December 2019): 46. a carrier of energy, a receptacle for the storyteller’s silent force. White believed the nature of the photograph was not to document, represent, or symbolise, but to create a felt space. He imagined it could be a ‘splinter of divinity in the world’,Bourland, 46. an energetic space carrying the stories of the human spirit.

The desert painter and mystic Agnes Martin (1912-2004) employed stringent means to achieve transcendent reality. Her grid paintings meditate on beauty, joy, innocence, happiness, and love. Martin did not consider outward beauty a reality but rather a catalyst for an awareness of the beauty that already exists within 'the inner mind.'Nancy Princenthal, Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art (Thames and Hudson, 2018),93. She believed her paintings were closer to a sound than a visual experience. Like a mantra in meditation, they undulate as a magnetic wavelength of existence.

Deep under the Whitby coast in England, physicists work in a laboratory set into a band of silver rock salt, as it is among the quietest places in Europe. In this underground laboratory, scientists look into a void and listen to the Universe. Large machines sweep the Cygnus constellation for the last breath of wind left over from the Universe's initial expansion.Robert Macfarlane, Underland: A Deep Time Journey (Penguin Books Limited, 2019), 55. They are listening for the ‘smudged echoes of creation’Paddy McAloon, ‘I Trawl the Megahertz’, track 1 on I Trawl the Megahertz, Liberty Records, 2003. vibrating in another corner of the Universe—the first movement from nothing, the first sound from silence; this emergence of creation ricochets still.

Intertwined throughout history, the alien-like octopus and the mythical Great Mother have been powerful symbols of female power and healing deities. Indigenous cultures use the octopus as an otherworldly motif of immortality and infinity, a mysterious creature whose spiralling limbs and consciousness-suffused body evoke the ongoing creative expansion of the Universe.Miranda Bruce-Mitford, Signs and Symbols: An Illustrated Guide to Their Origins and Meanings (DK, 2019). In the depths of the Earth’s oceans, the mother octopus delivers her young safely into the world, and then she disintegrates back into the salt sea, becoming part of the life cycle once again.Peter Godfrey-Smith, Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness (William Collins, 2021), 170.

Shortly after my daughter was born, a writer and midwife called my studio. She sought a portrait for her book: stories from her lifelong experience in maternity wards. She believed childbirth to be a transcendent experience far beyond human understanding. She spoke of women travelling beyond the realms of the physical world, far off into the cosmos, beyond the Earth plane. She spoke of a mother calling their child’s spirit towards her, like sonar, as her consciousness vibrates with the etheric message, ‘Come to me, come to me.’ She spoke of how, eventually, the mother reaches the black velvet, the nothingness. She spoke of how the mother knows she has called forth her child from deep beyond the cosmos, and everything is complete.Bríd Shine, Between Worlds: Shared Reflections of a Spiritual Midwife (Bealtaine Press, 2021), 93.

Through her work Circles and Spirals, Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), the French–American artist, explored the constant continuation of birth, life, and rebirth and that connection with motherhood. Bourgeois created these circles not only to replicate a celestial motion but also to participate in it. Her use of mythological and archetypal imagery searched the skies for universal balance ‘as the beginning of movement in space’.Louise Bourgeois, Spirals (Damiani, 2019).

In her visionary 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula Le Guin (1921-2018) suggests that our ancestors’ greatest invention was the container, ‘the place that contains whatever is sacred.’Ursula Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (Ignota Books, 2021). Le Guin understood the significance of a container, a womb, a story, to hold things that bear meaning.

The birth of my daughter, the cosmic catalyst, created an energetic space in my world. What a privilege to be ‘the recipient, the holder, the story. The bag of stars.’ This personal story is a meditation on the resonance of existence, the imprints and echoes that help us to ‘relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story.’Le Guin, 37.

Hiền Hoàng, Scent from Heaven (2022–ongoing)

Still from the performance, performed by Moe Gotoda, camera by Rika Malottke, costume by Sanja Philipp, photo by Antine Yvez. Directed and produced by Hiền Hoàng. Courtesy of the artist.

Hiền Hoàng

1. How would you define spirituality through your work? Where would you locate it, and for what reason?

Spirituality in my work is an ethereal thread that runs through the material and immaterial realms. In projects like Scent from Heaven, spirituality is found in the convergence of various elements – the scent of agarwood, the hidden stories of pain and redemption, and the merging of physical and virtual spaces. The essence of spirituality resonates in the immersive experiences I create, challenging viewers to explore the layers beneath the surface. I locate spirituality in the interplay of nature, technology, and human emotion. In this way, I aim to evoke a deep sense of connection to something that is close to us but invisible, like the pain of trees, and invite reflection on the interconnectedness of life.

2. What kind of myths, traditions, or cosmologies are you invoking?

In my work, I draw on the myths and traditions surrounding agarwood, a material that is of great cultural significance. From Asia to the West, agarwood has been revered for centuries for its spiritual and healing properties. The project embraces cosmologies that view nature as a path to transcendence. By combining modern technology with ancient narratives, I aim to create a dialogue between cultural heritage and contemporary art. This convergence allows me to reawaken these myths in a way that resonates with the present, and to create connections between time-honoured traditions and cutting-edge forms of expression.

Hiền Hoàng, Across the Ocean (installation view), as exhibited at the MOVING DEFINITIONS. DISCOVERY AWARD 2023 LOUIS ROEDERER FOUNDATION exhibition, Rencontres d'Arles (July–August 2023), Arles, France. Curated by Tanvi Mishra.

Photo by Philippe Calia. Courtesy of the artist.

3. What is ‘energy’ to you?

In photography, energy is the invisible force that gives images a life beyond the visual. Just as agarwood carries a hidden story within its grains, photography captures the energy inherent in a moment or subject. This energy transcends the boundaries of the image and radiates emotion, stories, and connections. As my work exhibited at the Rencontres de la photographie in ArlesHiền Hoàng, Across the Ocean, 2023, multimedia installation. Exhibited at Moving Definitions: Discovery Award 2023 Louis Roederer Foundation, curated by Tanvi Mishra, Rencontres d’Arles, 3 July to 27 August 2023. demonstrates, I explore how photography can be sculptural, tangible, and malleable by transforming traditional two-dimensional images into three-dimensional experiences. This adds another ‘layer of energy’ and bridges the gap between the real and the imagined, the past and the present.

Sebastian Koudijzer, The Awakening (2021), from The Strange Familiar.

Sebastian Koudijzer

1. How would you define spirituality through your work? Where would you locate it, and for what reason?

During the process of making The Strange Familiar, spirituality came to me, so to speak. The preliminary research for this work began with the mystical sword: the Keris. This object can be found all over the Indonesian archipelago and surrounding countries in different variants. It intrigued me because I had photographed my Javanese–Surinamese grandfather with his own Keris in 2018. When I wanted to photograph the object again three years later, to my surprise he told me that he had discarded his Keris because his church leader told him it did not go with Christianity. The research led me to a Dukun, a traditional Javanese healer who introduced me to different traditions and rituals. I recognized more and more practices that I could remember from my childhood, which I largely spent with my grandparents. They took me and my brother to visit many Javanese relatives and friends. After a number of visits to the Dukun, I became so fascinated that I found that I could no longer just observe – I also enjoyed participating. Spirituality gave me a sense of connection to my Javanese ancestors. There is a certain fear of Javanese mysticism among the Javanese community. This is because it is true that with bad intentions, you can also bring bad outcomes upon yourself. Therefore, there are many ‘horror’ stories where, for example, the Keris has harmed its owner. I want to show the beautiful side of spirituality, where many people get support and direction. To bring tradition out of the shadows. That is why I think it is important that the work can be found in places that are accessible to a large audience. Like, for example, a museum such as the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, where it was exhibited in early 2023. But I also respect the fear and therefore will not push it in people’s faces uninvited.

2. What kind of myths, traditions, or cosmologies are you are you invoking?

The form of spirituality is called Kejawèn. It is a way of living that is not bound by a fixed list of rules. It has many influences from animism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. I usually offer my Keris once every thirty-five days or so, but it is not mandatory. The thirty-five days are based on the current Gregorian calendar combined with the ancient Javanese calendar, which has five days in the week. If you superimpose these two ways of counting the week, you have thirty-five different combinations of days. I prefer to do my offerings on Selasa Kliwon (Tuesday Kliwon). On this day, I offer my Keris the five elements: ether, earth, water, air, and fire. Furthermore, the Gunungan always really speaks to my imagination. That is the cosmic mountain or the tree of life. The fascinating thing about the tree of life is that you can find this symbol in many ancient forms of spirituality, such as ancient Norse mythology. Therefore, while I am convinced that the form that I practice is a cultural product, if we go much further back in time it is ultimately all one, where everyone had the magic within themselves. I still believe it is possible that every individual in this world can find that power within themselves.

Sebastian Koudijzer, The Keris & Crocs (2018), from The Strange Familiar.

3. What is ‘energy’ to you (in relation to photography)?

Energy, in relation to my work, is a reminder to me. I have captured moments of energy in my search for spirituality and the ancient traditions. I have been able to experience peaks of spirituality through this search, experiencing certain moments in a completely different state. However, this is not a constant factor, and sometimes I also lose my sense of spirituality. When I look back at my own work, it functions as a reminder of the times I was allowed to experience that. It makes me stop and think about how I can bring spirituality back into my life. I sometimes used to feel guilty when I realized I had lost this feeling. But now I know that it comes in waves and that sometimes life also requires a rational view for a moment. However, this reminder remains very functional for me personally – it is a commitment I made to myself, to the Earth and the Universe.

Léonard Pongo

Shot across the country of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Léonard Pongo’s ongoing Primordial Earth series (2020) builds a relationship with its natural landscape, transcending both the material and the photographic document by generating what we could call ‘opaque’ energies.On ‘opacities’, see Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s essay ‘Spectacular Opacities’ in his Dark Mirrors (MACK, 2021), where the particular nuances are clarified: ‘Opacity here does not mean absence in relation to some simple act of erasure, nor does it signal a simple occultation, intellectual or moral obscurity, as its etymological origins suggest. Rather, . . . opacity offers us a “trope of darkness” which “paradoxically allows for corporeal unveiling to yoke with the (re)covering and re-historicizing of the flesh” in performances that “contest the ‘dominative imposition of transparency’” systematically willed on to Black figures.’ (236)

Pongo’s use of a full-spectrum camera captures light invisible to the traditionally engineered camera and allows intimate closeups of botanical ‘wonders’ inspired by Kasaian cosmogonies.

For Trigger, Pongo extracted fragments from his previous and new film, part of the larger project. What interests him is how repetition and the moving image alter the relationship to (linear) time. Pongo here highlights little changes in position, light, and shape. By showing different versions of the ‘same’ thing, something else happens.

Pongo’s photographic work steps away from the ‘extractive’ logic to which his country was and still is submitted. First, his meditative approach embraces more than the physical dimensions of the land. When it comes to changing the course of global warming, the Congolian rainforest – the second largest tropical rainforest in the world – is a regenerative force in its ability to absorb carbon emissions and protect biodiversity. Second, this work reimagines modes of relations to the African environment, the imperial plunder of which has had devastating consequences for both the continent and globally as it continues to propel today’s climate crisis. It tries to look at that environment away from any preconceived history or frame of references. For this, Pongo relies on layers of indigenous memory, history, genealogy, and cosmogony as well as poetry and natural cycles including death and life.

If anything, Pongo’s work is poetic, intimate, and emotional for a ‘spiritual’ reason. To quote researcher and curator Sandrine Colard:

Away from Western anthropocentrism that has considered all fauna and flora at humans’ disposal, or from an exoticization of the tropical landscape, Primordial Earth series’ majesty and beauty awe spectators into regaining a position of humility in relation to the land. . . . Photographic rendering of what is impalpable and unquantifiable emanates from the artist’s intention to draw an emotional landscape of Congo’s forest, when they have been the object of unreasonable exploitation and ecocides, and their original populations often displaced by the creation of national parks, such as Salongo. . . . Through atmospheric colours, sfumato and plays of light and shadows, Pongo dramatizes the equatorial forest as more than a backdrop, but as the global climatic and spiritual actor that is thousands of years old.Sandrine Colard, ‘Three Congolese Latitudes in a Changing Climate: Sammy Baloji, Léonard Pongo, and Kiripi Katembo’, A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography, ed. Osei Bonsu (Tate Publishing, 2023), 50.