Soha (Muma’s Photographs), 2019, from Buttons for Eyes, 2017-ongoing by Priya Kambli. From Photography – A Feminist History by Emma Lewis

Missing Women: Photography's Ongoing Issue

Four recent publications show that women are just as capable of producing great photographs as men, and always have been.

Diane Smyth

12 jan. 2022 • 14 min

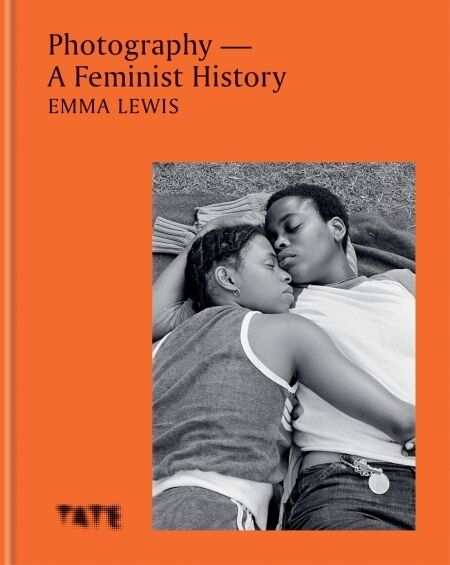

‘Perhaps the most immediate work of a feminist history is to reclaim some space from the male-dominated narrative’, writes Emma Lewis in the introductionEmma Lewis, Photography – A Feminist History

(London: Ilex Press, 2021), 13. to Photography – A Feminist History, which she published this year with Ilex Press. Her book is a case in point, a beautifully illustrated survey that convincingly shows how women have used photography since its inception. Part chronological, part genre-based, it runs from the nineteenth century to the present day and includes both familiar and less known names. There’s Dorothea Lange, Susan Meiselas and Cindy Sherman, for example, but there’s also Maryam Sahinyan (Turkey’s first female professional photographer), Sheba Chhachhi (an activist within India’s feminist movement) and Amalia Ulman (an Argentinian artist who staged an elaborate hoax on Instagram). Each chapter has a generous introduction, and each featured photographer gets her own spread.

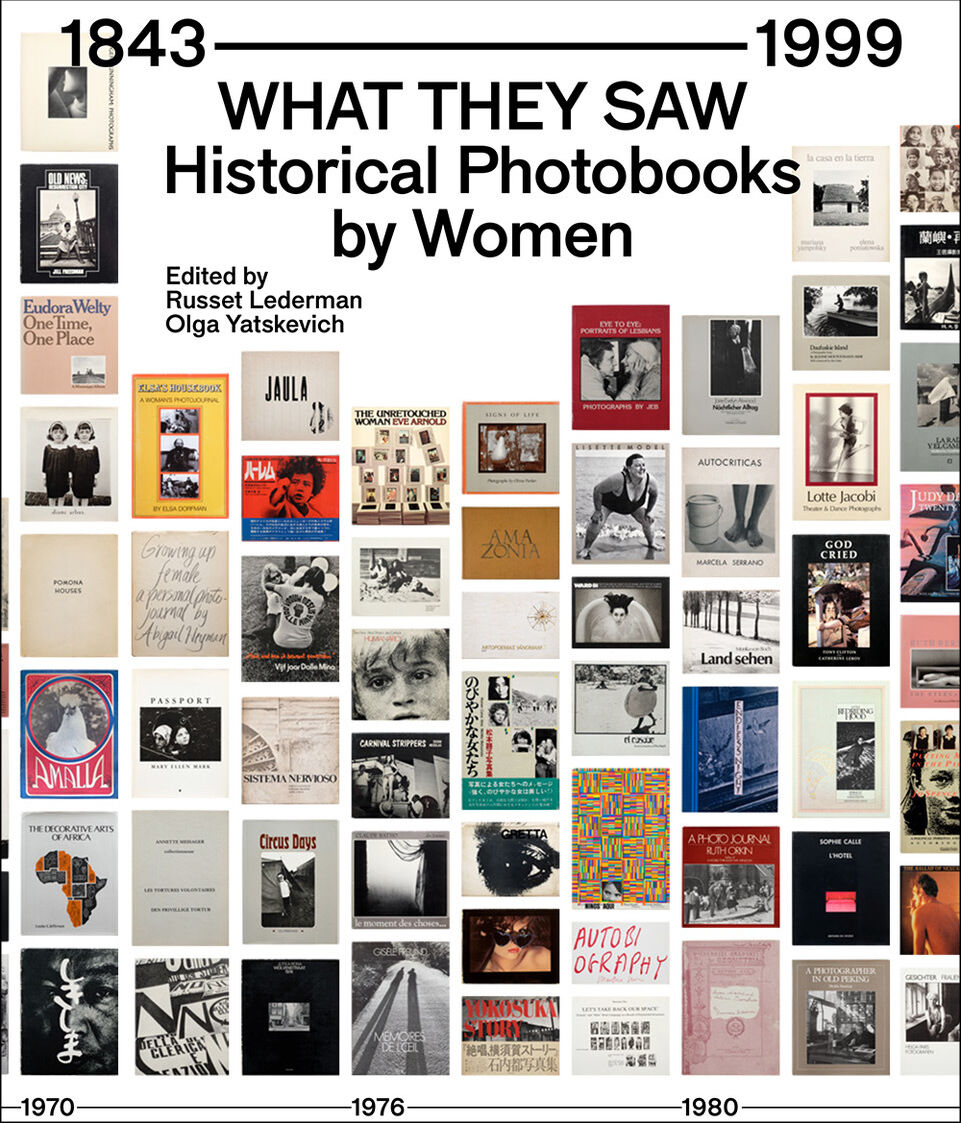

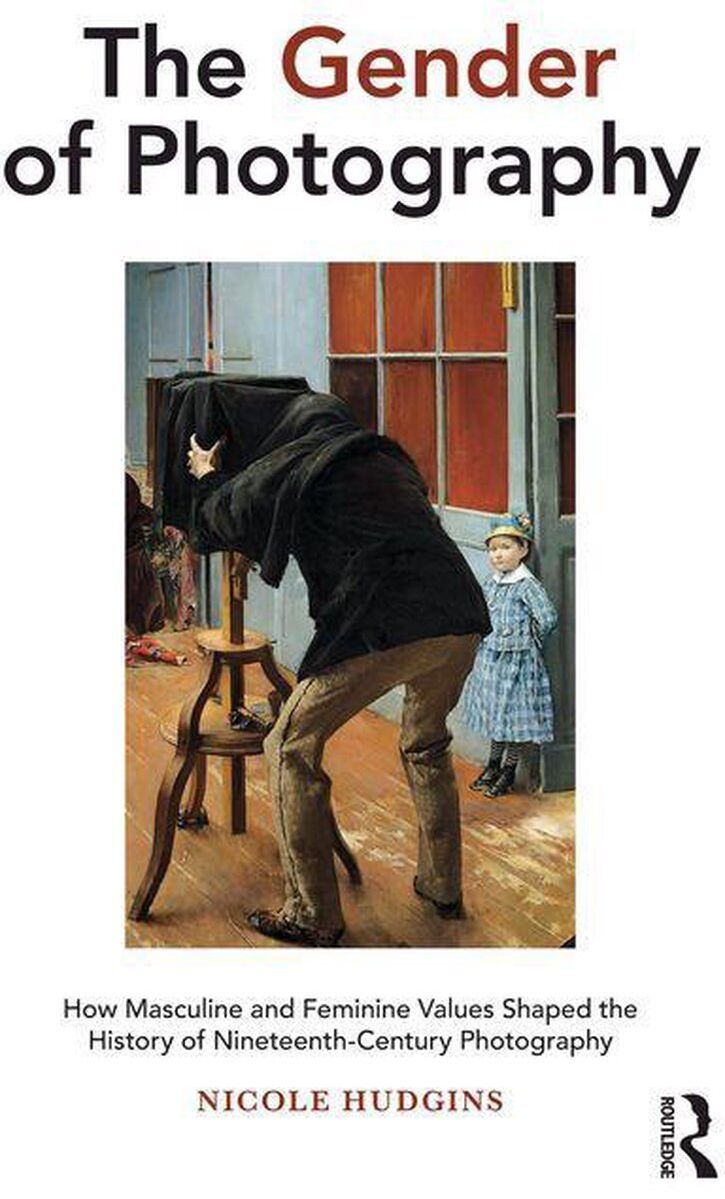

Photography – A Feminist History is one of several surveys of women’s photography to come out in the last year or two, each focusing on a slightly different aspect of the topic. There’s What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, published by 10x10 Photobooks, NYC in 2021 (and the follow-up to How We See: Photobooks by Women by the same editors and publisher in 2019). In French but coming in English soon is Une histoire mondiale des femmes photographes by Luce Lebart and Marie Robert (Editions Textuel, 2020). Nicole Hudgins’ The Gender of Photography – How Masculine and Feminine Values Shaped the History of Nineteenth-Century Photography, published in 2020 by Routledge, is more academic and less image-driven, but it’s a fascinating read.

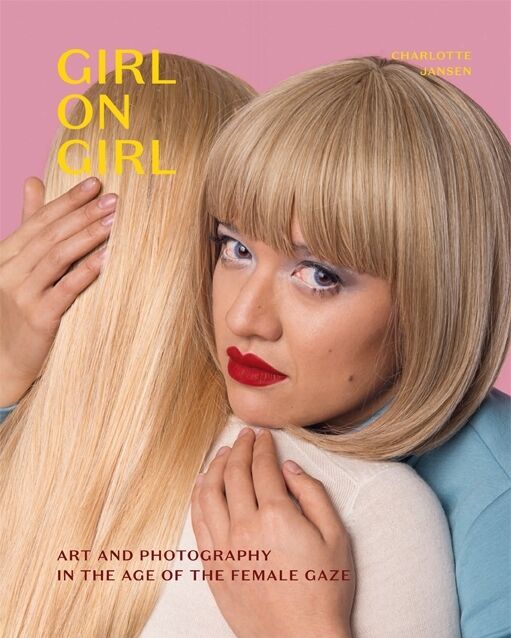

Focusing on contemporary image makers there’s Women Street Photographers by Gulnara Samoilova (Prestel, 2021), a photo-led compendium which includes an illuminating short history of the genre. Girl on Girl – Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze by Charlotte Jansen covers contemporary women photographers who shoot women and was published by Laurence King a little earlier, in 2017. Expanding the field there are books on women’s art which include photography, such as Contemporary Art and Feminism by Jacqueline Millner and Catriona Moore, published by Routledge in 2021, which, while also being more text-driven, includes a first chapter largely devoted to photo-media.

And that’s just the books. Added to this are the numerous magazines, exhibitions and organisations which have popped up to promote women’s photography, both contemporary and historical, in big-name institutions and at grassroots level. The New Woman Behind the Camera which ran at The Met from 2 July to October 2021 was pitched as a ground-breaking exhibition on women’s photography from the 1920s through the ‘50s, for example, while Underexposed: Women Photographers from the Collection at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art (from 17 April to 1 August 2021) was a significant step for an institution whose permanent collection is dominated 9:1 by works by men. The Instagram account @africanwomenphotography and feminist magazine Gaze both set up to promote women’s perspectives in 2020, to take just a couple of examples from a much wider and richer field, while researcher Delphine Bedel published an insightful essay on Medium on 07 October 2021, titled ‘How Women invented the Photobook?’.

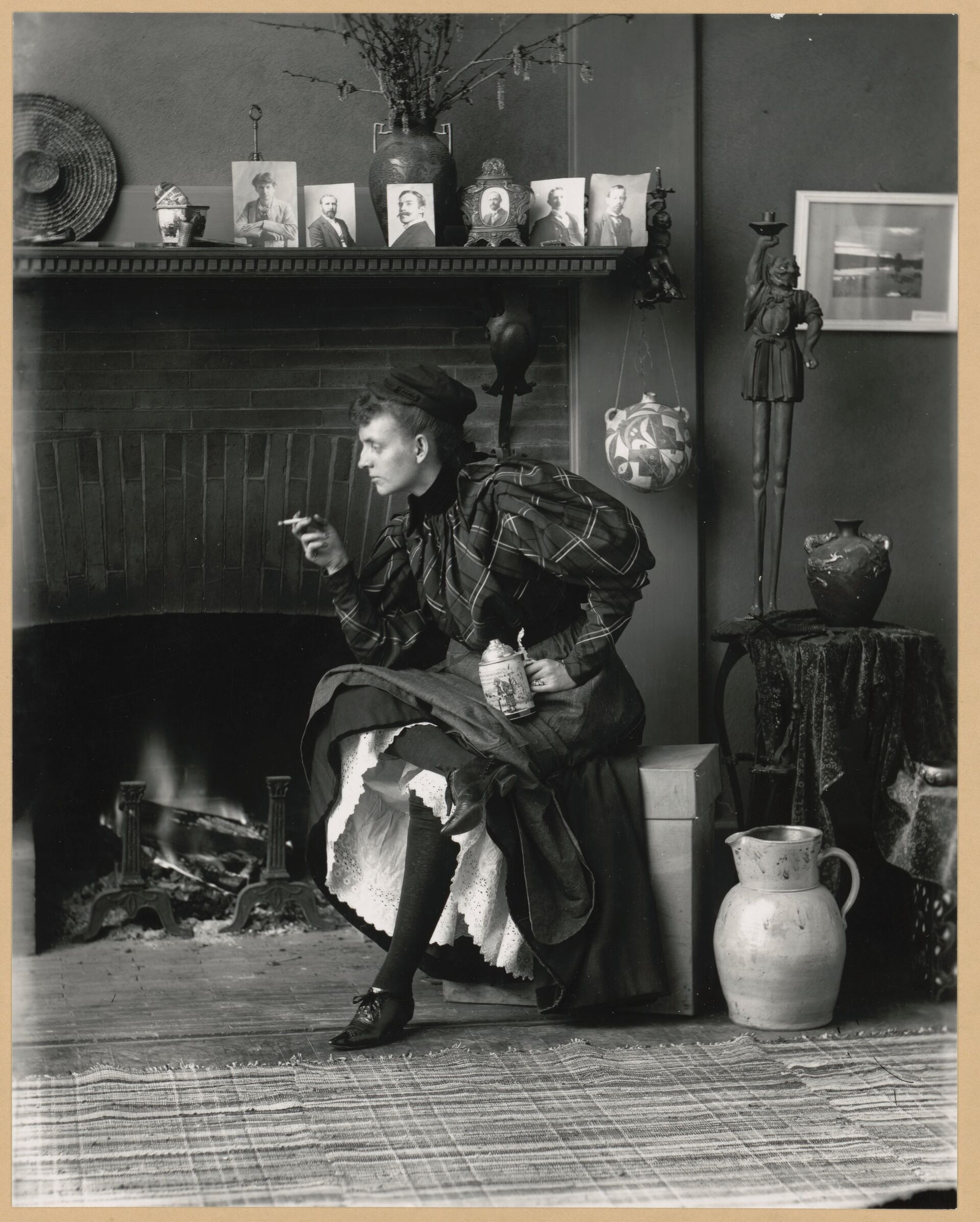

Self-Portrait (as ‘New Woman’), 1896 by Frances Benjamin Johnston. From Photography – A Feminist History by Emma Lewis

I’m focusing here on four books – Lewis' A Feminist History, Lederman and Yatskevich's What They Saw, Hudgins' The Gender of Photography, and Jansen's Girl on Girl – but even these few publications show that women are just as capable of producing great photographs as men, and always have been. The problem was (and still is) their work can fly under the radar. Western women working in the nineteenth century faced issues around respectability and property-owning, for example, which meant they often opened joint commercial studios under their (male) partners’ names and attributed their work to their spouses This didn’t just happen with studios. ‘Sadly, many of their collaborative books are credited only with their husbands’ names, and their contributions, if mentioned at all, are included as footnotes’, write Lederman and Yatskevich. ‘In some cases, women authors marked their works with a gender-neutral signature that used only their studio name or their first initial and last name.’Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999 (NYC: 10x10 Photobooks, 2021), 5.

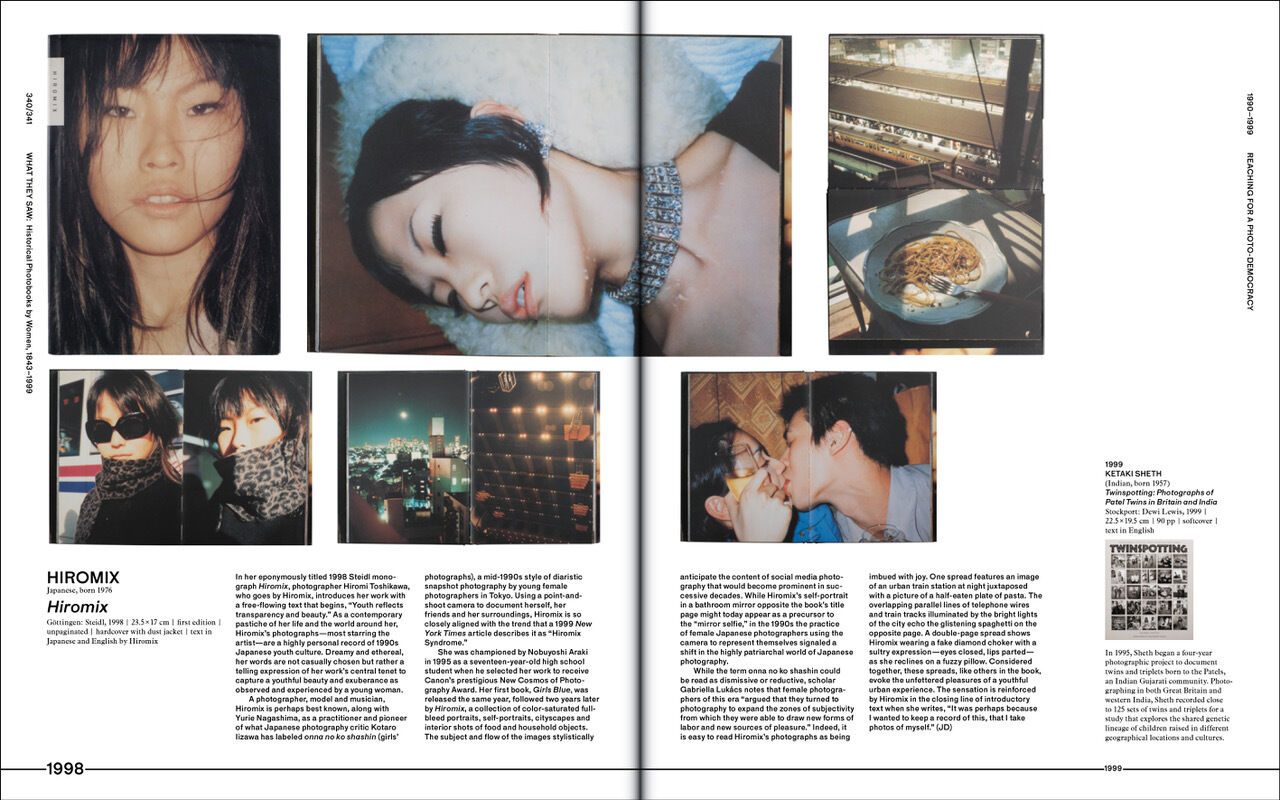

Spread devoted to Hiromix' Hiromix (1998) in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich.

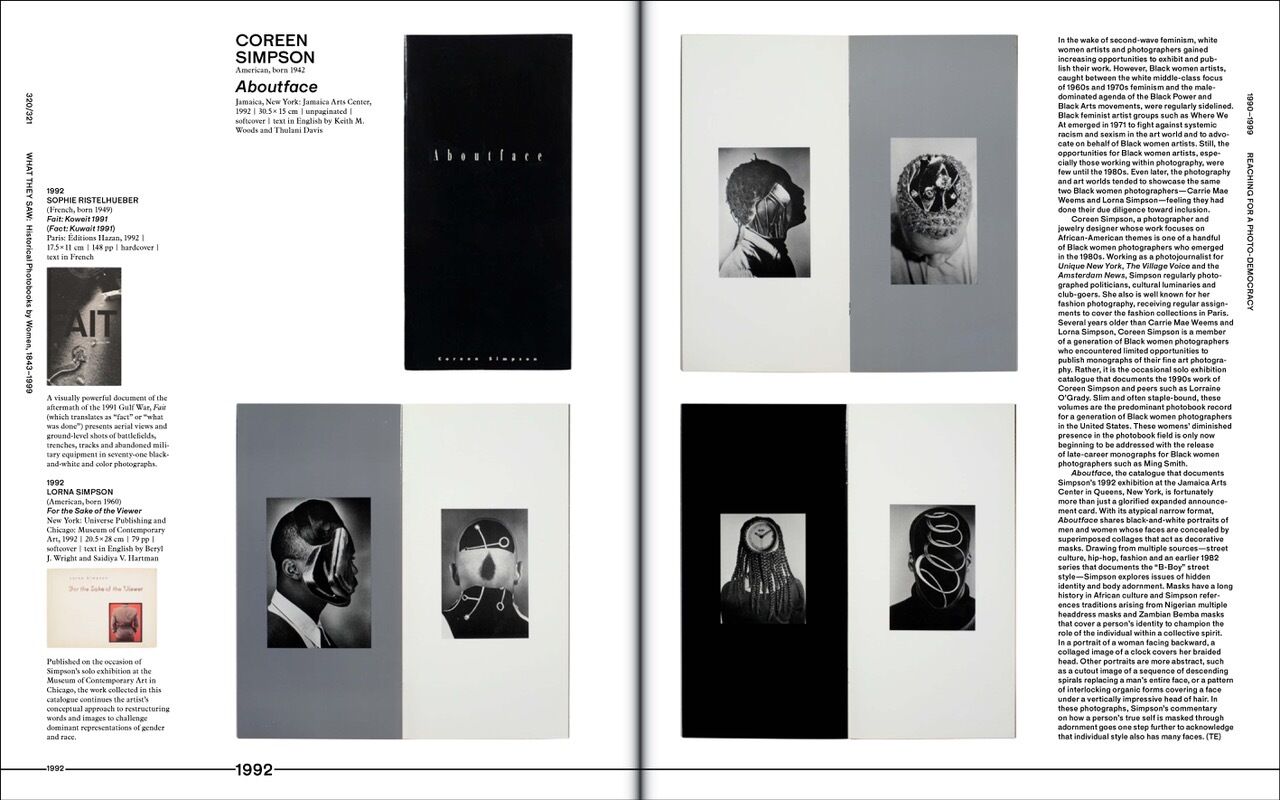

Spread devoted to Coreen Simpson and her book About Face in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich. Photos by Jeff Gutterman

Assumptions over women’s intellectual abilities also meant that their contributions were downplayed, as happened to Constance Fox Talbot (the first woman to take a photograph) and Gerda Taro (the radical photojournalist); women who did create large bodies of work, such as Lee Miller, somehow became better known as muses. Others, such as street photographer Vivian Maier, seem not to have pursued exhibitions or publication, working alone in obscurity. The reasons for Maier’s reticence are unknown, but presumably the obstacles and humiliations she would have faced didn’t help, and hint at the social and psychological hurdles faced by women who might have pursued professional advancement. To this day, commentary on Maier often emphasises her apparently peculiar nature – the fact that she was unmarried, sometimes ignored the children she nannied and locked herself in her room – as if these factors weren’t crucial in allowing her to work.

Seeking out these hidden examples of women photographers involves intensive research. Hudgins’ groundwork included studying unpublished graduate theses, for example, including the odd one that ‘stood by itself as a voice in what may have been a hostile wilderness at the time that it was written’; she gives thanks for what she terms ‘these instances of courageous and painstaking scholarship.’Nicole Hudgins, The Gender of Photography – How Masculine and Feminine Values Shaped the History of Nineteenth Century Photography (Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2020), 6-7. Despite the difficulties, what emerges from these books is the sheer wealth, breadth and scope of women’s work, from Poulomi Basu’s hard-hitting documentary images to JEB’s intimate work with lesbians, to Tabita Rezaire’s probing of black womxnhood to Hiromix’s intense vision of Japanese youth.

Cutbacks, 2017, from The Dream is Wonderful, Yet Unclear, 2014-20 by Maria Kapajeva. From Photography – A Feminist History by Emma Lewis

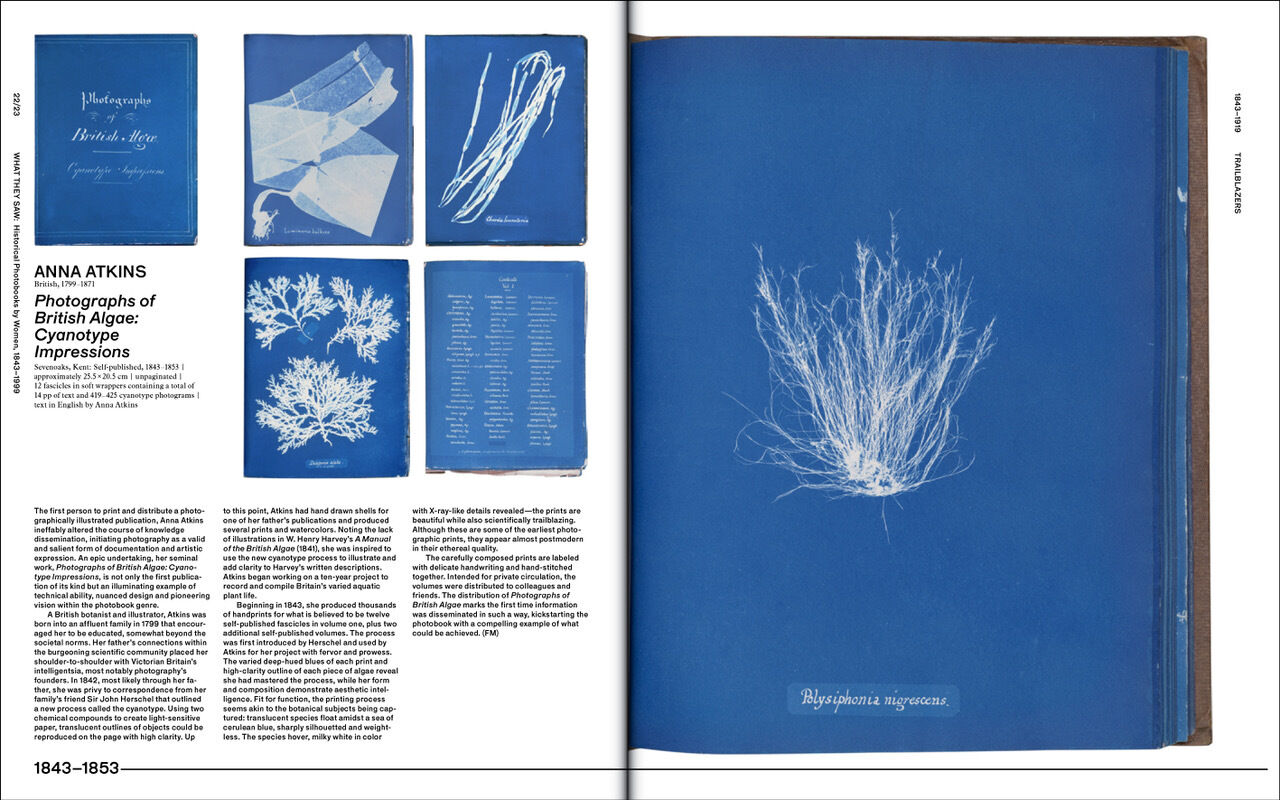

Spread devoted to Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich. Images courtesy The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Perhaps because of this wealth, the authors (other than Jansen, and the Broadly Magazine editor Zing Tsjeng in Girl on Girl’s foreword) avoid speculating on the ‘female gaze’, the idea there’s a way of looking inherent to women. In fact, Lewis takes on this term, pointing out how assumptions of overarching perspectives can flatten non-Western or alternative viewpoints. ‘There is no one gaze – singular, monolithic, oppressive – but rather gazes, plural’, she states, later adding, ‘while “female gaze” can sound empowering, if it is used too bluntly it can also suggest that all women see the same way.’Lewis, A Feminist History, 113. Still, as Lewis also highlights, being a woman makes a difference because it affects one’s experiences, as it always has done. ‘It is possible to identify commonalities in ideas about photography without making reductive generalizations’, she states. ‘And, arguably, it is essential to do so in order for progress to be made.’Lewis, A Feminist History, 13.

Interestingly, Hudgins’ work suggests a similar flaw around the ‘male gaze’, the term against which ‘female gaze’ is defined. The ‘male gaze’ came first as a concept, coined by Laura Mulvey in ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (written in 1973 and published in 1975) as a way to sum up a certain power relation between the men who dominated filmmaking (and beyond) and the women who appeared in their movies (and beyond). ‘In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active male and passive female’, Mulvey wrote. ‘The determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.’Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ in Visual and Other Pleasures (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), 19, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/architecture/ockman/pdfs/feminism/mulvey.pdf.

Hudgins’ text suggests the ‘male gaze’ might not be so monolithic. Focusing on the US, UK and Europe in the nineteenth century, she picks out the ‘masculine’ qualities encouraged in men at the time, especially the wealthy white men involved with early photography and whose values shaped the medium – bold action, physical and intellectual strength, and a certain degree of ruthlessness, the kind of mindset useful for colonisation. ‘Whether in the context of the Imperial-Republican France, the British Raj, or Manifest-Destiny America, it seems clear that these masculine credentials were linked to empire-building, not just in the sense of distant territories, but empires of knowledge as well’, she writes, adding that these practices relate to ‘conquest’, ‘first and foremost, the drive to conquer the unknown and make visible.’Hudgins, The Gender of Photography, 21.

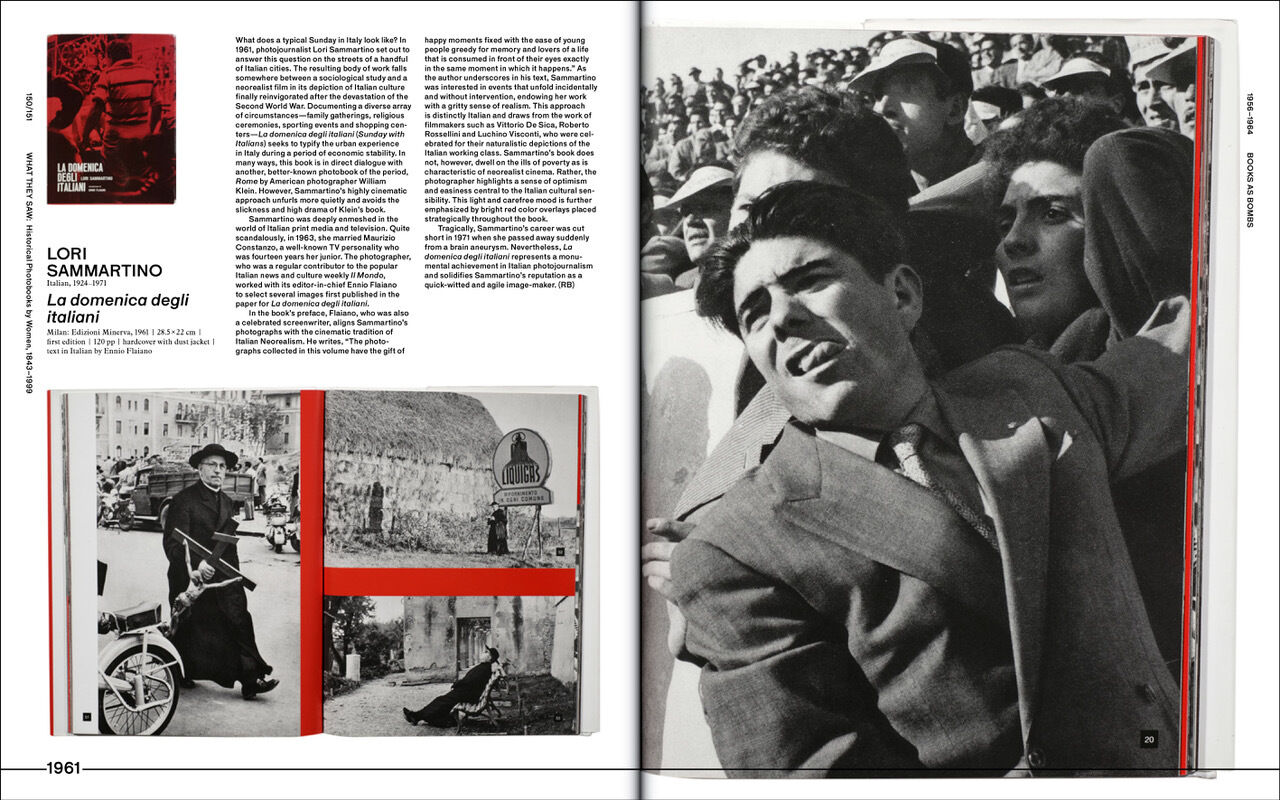

Spread devoted to Lori Sammartino and her book La domenica degli Italiani (1961) in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich.

As such, this ‘male gaze’ is particular, excluding men of other races, classes, sexualities and even personality types as well as women, despite having been passed off as universal. If it persists in photography – despite efforts by theorists such as Susan Sontag to unpick the medium’s problematic power relationships – then women and other so-called minorities may need to altogether rethink images and image-making. That means doing more than just filling in gaps. As Hudgins point out, there have been surveys of women’s photography before, starting with Naomi Rosenblum’s ground-breaking A History of Women Photographers, in 1994. And yet somehow, they’re still needed now. ‘Despite the impressive corpus of biographies and exhibition catalogue dedicated to the work of women photographers of all eras, the knowledge it offers has not led to real change in the format of our surveys, textbooks or museum exhibitions’, she writes. She continues:

Such accounts of photography’s history and its many uses will be improved by correcting the historical imbalance of values, not simply by adding women’s names and achievements to conventional accounts. To paraphrase Cambridge anthropologist Henrietta Moore, the “add women and stir method” will not repair a deeply-rooted bias.Hudgins, The Gender of Photography, 2.

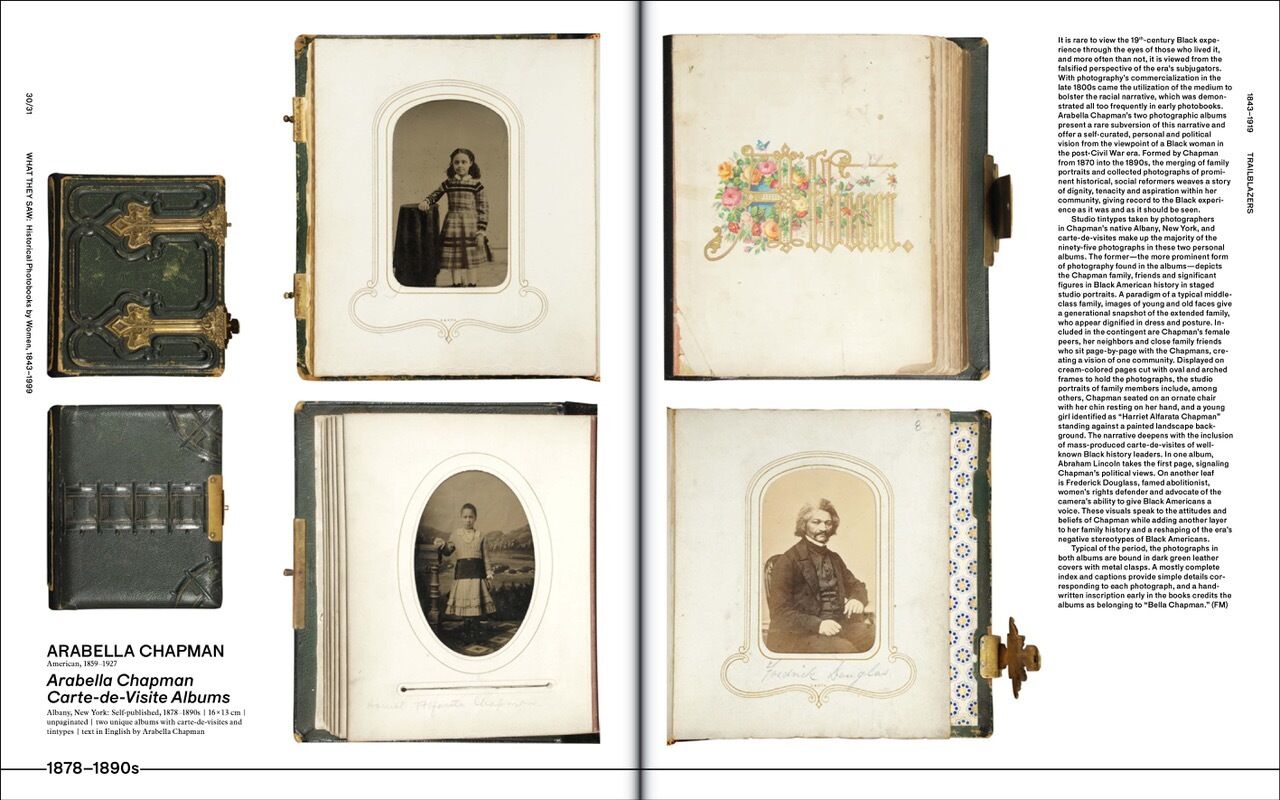

It’s an intriguing insight, and one that recurs in these books. Lewis states in her introduction, for example that ‘we can find fresh and illuminating ways of thinking about photographs and their makers’Lewis, A Feminist History, 9. while Lederman and Yatskevich position their book as ‘a necessary step in the unwriting of current photobook history and a rewriting of a photobook history that is more equitable and inclusive.’Lederman and Yatskevich, What They Saw, 5. Hudgins highlights scholars such as Patrizia Di Bello, meanwhile, whose research has helped reshape attitudes towards Victorian scrapbooks and albums. Predominantly made by women in very small numbers for private consumption, these albums were traditionally written off as domestic, but can be interpreted as an important expression of creativity and culture at a time when more public outings were limited.

Spread devoted to Arabella Chapman’s Carte-De-Visite Albums in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich. Images: Collection William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

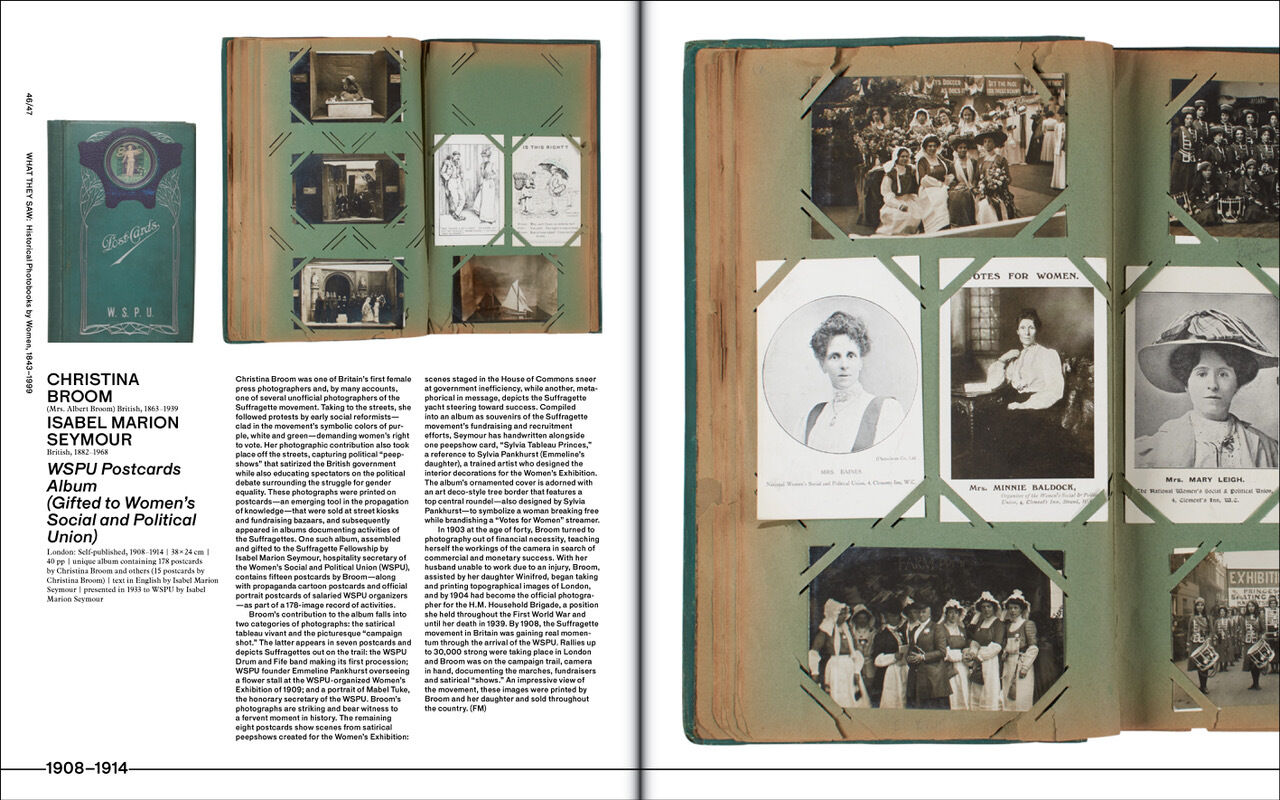

Spread devoted to Christina Broom and Isabel Marion Seymour's WSPU Postcards Album in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich.

Hudgins also considers nineteenth-century women’s work with ‘dressing up’ – playing with alternative roles at home or in-studio – when pursuing alternative lifestyles, or even leaving home unchaperoned, brought heavy penalties for ‘respectable’ Western women. Understood in these terms, this work was a sophisticated reaction to these women’s lived experience (which perhaps explains its enduring popularity), as Hudgins points out. Yet its association with femininity and childhood meant it was often undervalued. Another fundamental rethink is the role of collaboration, which is still downplayed in favour of the romance of the lone artist working without assistants, printers or retouchers, leaving no room for any sense of a wider cultural milieu, to say nothing of the uncelebrated souls handling the housework and kids. Collectives and collaborations were big in the radical 1970s and have come around again now; Ariella Aisha Azoulay, Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, Leigh Raiford and Laura Wexler are currently writing a book on collaborative photography.

It’s the start of an ongoing process, and Lederman and Yatskevich invite others to join the effort; both their book and the others suggest some intriguing possible directions. For example, Lewis includes a whole chapter on ‘Herstories’ (with the subtitle ‘The Family Album and the Photographic Archive’) but only features family photos which have been reworked by artists. Perhaps family photographs could also prove a rich area in their own right. Often made by women, they are also often dismissed as ‘family snaps’, of interest only to those pictured; as such they seem ripe for one of the tasks of feminism as set out by Lewis, namely ‘to make women credible and audible.’Lewis, A Feminist History, 9. As Jansen writes:

We see photographs women take – even of other women – as narcissistic, shallow, easy. This confluence of meanings doesn’t benefit photographers or viewers. We often miss the nuances that reflect, in varying degrees, the photographer’s perspective of living in our times.Charlotte Jansen, Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2017), 9.

And in thinking through ‘living in our times’, perhaps it’s worth considering the work that won’t appear in any surveys, no matter how extensive the research or progressive the values, simply because it was never made. Historically, there are fewer images by women because they were unable to take them. ‘Respectable’ nineteenth-century Western women couldn’t go out alone, or sell work, or get messy, were unlikely to have had enough education to understand chemical processing and weren’t supposed to call attention to themselves or waste time on their own projects when they could be out helping others. Women who weren’t in a position to worry about respectability didn’t have the time or the money for photography (and that went for men too). Then there were the myriad issues faced by women – and others – who were gay, transgender, not white, born outside the West, and so on.

Sathyarani, Anti Dowry Demonstration, Delhi, 1980, from Seven Lives and a Dream, 1980-91 by Sheba Chhachhi. From Photography – A Feminist History by Emma Lewis

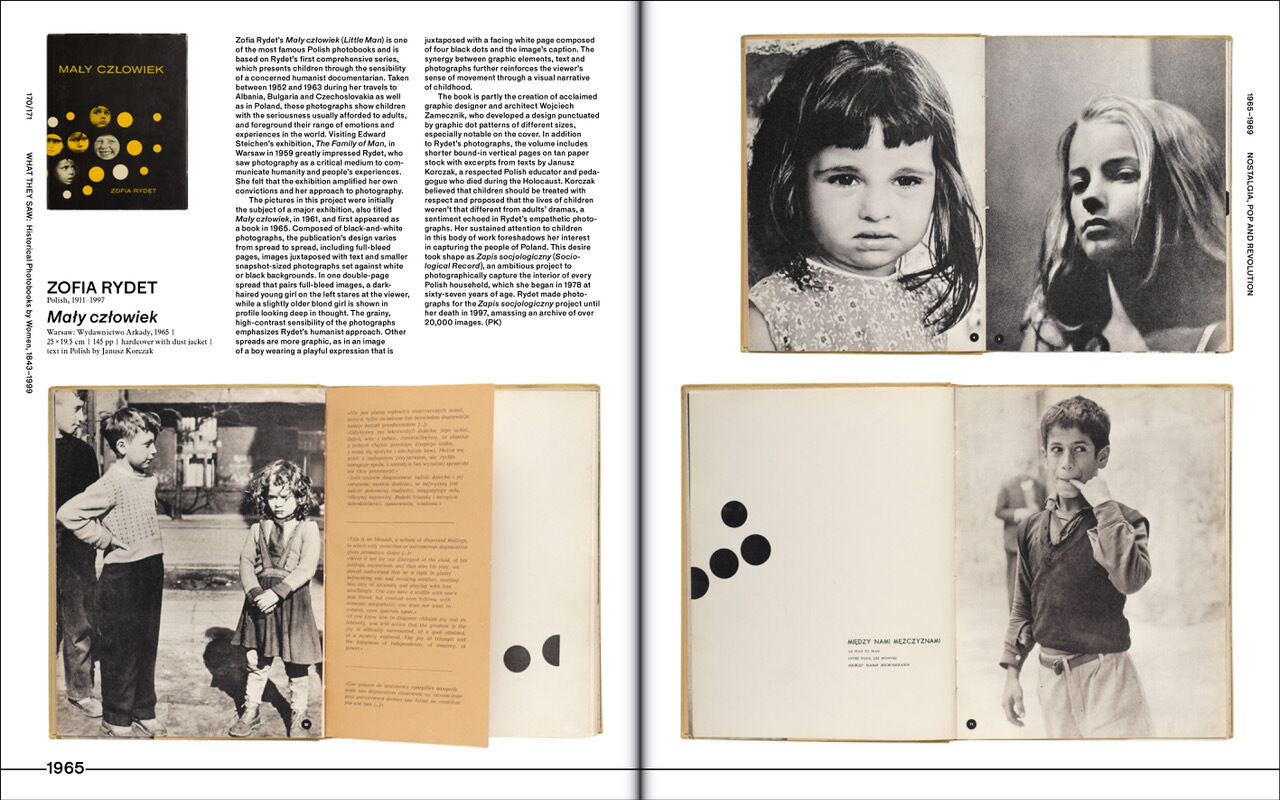

Spread devoted to Polish photographer Sofia Rydet and her book Maly Czlowiek in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich. Images courtesy Zofia Rydet Foundation

Children protest outside the YMCA, Jackson, Mississippi, 1969 by Doris Derby. From Photography – A Feminist History by Emma Lewis

It’s easy to assume that women have won many of these battles, that female photographers are now on a level playing field at least as far as gender goes; Mariama Attah writes in her essay in What They Saw that ‘hindsight and distance allow us the benefit of wondering, from the comfort of our positions of privilege, why the women didn’t try harder, work more diligently, find ways to support their dreams or overthrow systems that blocked them from achieving their fullest potentials.’Lederman and Yatskevich, What They Saw, 8. But perhaps our current positions still aren’t so privileged. In the apparently liberal West, #metoo has shown that women are still regularly sexually harassed. In the UK, on average, a woman is killed by a man every three days.Julia Long et al., ‘Femicide Census 10-Year Report’, Femicide Census, 25 November 2020, https://www.femicidecensus.org/. Abkhazia, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua all have total bans on abortion. In Poland and Texas, changing laws meant accessing abortion actually got harder in 2021.

As Attah points out, we continue to ask the same questions about who can pursue photography and some of those questions are gendered – Attah asking, for example, ‘how women can achieve a balance between domestic responsibilities and professional opportunities.’Lederman and Yatskevich, What They Saw,12. The collage ‘Who’s still holding the baby’ still rings true, though it was created in 1978 by the Hackney Flashers collective. The UK’s first National Women’s Liberation Conference in 1974 included a call for free 24-hour nurseries in its list of crucial demands, something that now seems radical despite the fact the other three demands seem obvious, or at least worth fighting for (equal pay, equal educational and job opportunities, free contraception and abortion on demand). Given this, it’s interesting how many photographers in these books didn’t or don’t have kids. A photography that’s inhospitable to mothers is a photography that’s keeping some women out. And if it’s inhospitable to parents in general, it’s presumably also limiting fathers.

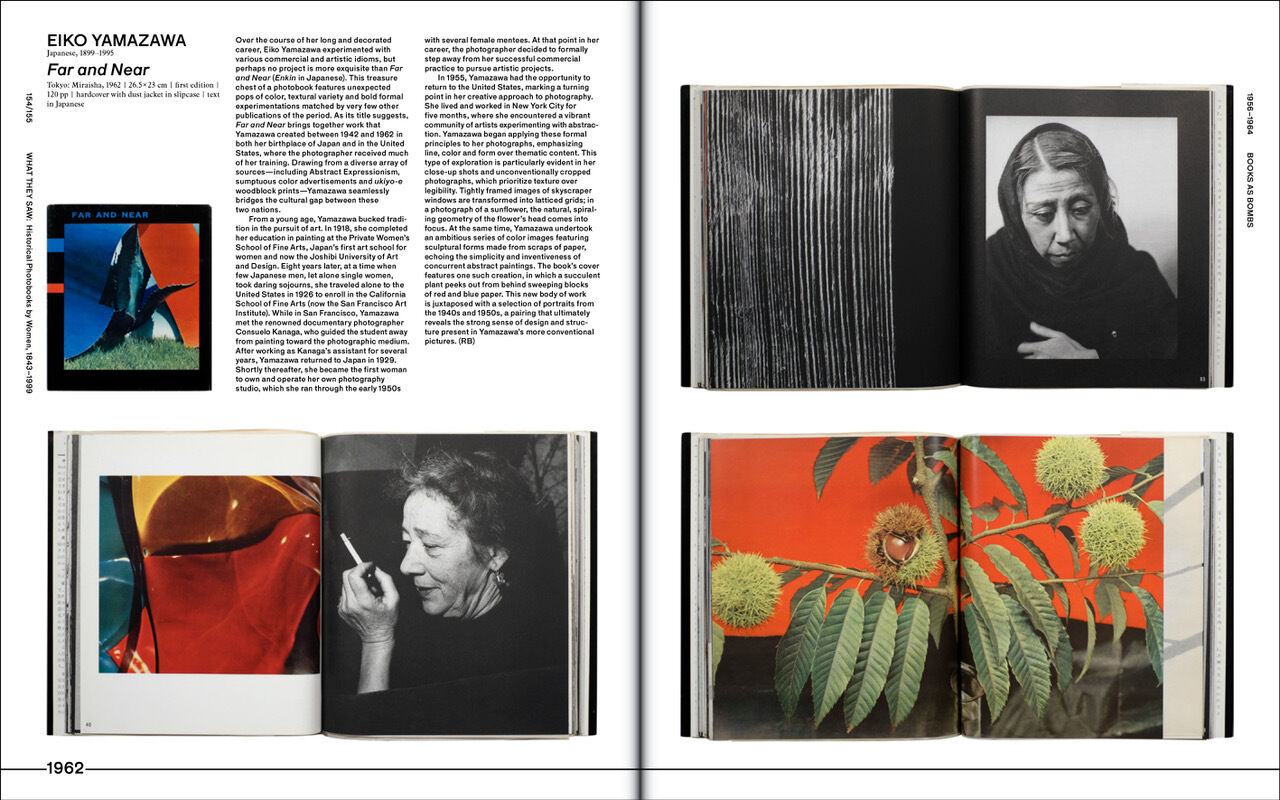

Spread devoted to Eiko Yamazawa’s Far and Near in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich

As Lewis writes in her chapter ‘On the Street: Documentary and Reportage in the “Golden Age” and Beyond’, ‘in 2020, the bylines for photo-led articles in the top news outlets ranged from a dismal 6.4 percent (Le Monde and The Guardian) to a could-do-better 35.7 percent in the San Francisco Chronicle.’Lewis, A Feminist History, 67-68. There are many reasons for these numbers, leaving aside the fact that documentary and reportage is a particularly macho field. Even so, these figures stink. Lewis’ book and the other books I’ve considered here are brilliant, fascinating, glorious testimonies to the images made by women. Hopefully there’s now enough critical mass to ensure they’re part of a wider cultural and social shift; if not, in future there will still be gaps.

Reviewed:

The Gender of Photography – How Masculine and Feminine Values Shaped the History of Nineteenth Century Photography. Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2020. By Nicole Hudgins

Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2017. By Charlotte Jansen

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999. NYC: 10x10 Photobooks, 2021. By Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich.

Photography – A Feminist History. London: Ilex and Tate, 2021. By Emma Lewis