PART I: INTRO // Which flavour of fascism do you want to live under?

‘Which flavour of fascism do you want to live under?’ It sounds absurd, like a sick joke, something blurted out mid-scroll between a war update and a protein-rich dinner recipe. But the question lingers. It hums beneath everyday choices, whispered behind casual headlines and algorithmic recommendations. It’s not just a joke anymore. It’s a grim inventory of options. A few months ago, after yet another morning of doom-scrolling through bad news in [please, insert country of choice here], I turned to my wife and said, ‘If we ever had to leave, maybe that’s the only real question left.’ Because wherever you look, from supposedly liberal democracies to proudly authoritarian regimes, the myth of political neutrality is disintegrating. Alternatives are limited every election, leaving a sense of different brands of crisis management in the air. Different intensities of surveillance, control, and collapse. Indeed, various flavours to choose from the same old batch, now rebranded.

Meanwhile, it’s all happening everywhere, all at once:If you didn’t get the reference to the movie, directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, go watch it. our feeds compress everything – wars, skincare tips, political scandals, meme trends – into the same endless scroll. Outrage becomes entertainment, while empathy is reduced to emojis and hashtags. Politics has turned into aesthetic warfare, fought with images. And then, my wife’s response to my tragic question couldn’t have been more fitting for the current zeitgeist: a Namaria Dança meme. The 500-by-500-pixel GIF captures famous Brazilian TV host Ana Maria Braga in a larger-than-life moment, dancing amid colourful bursts of debris. It’s over the top, deliberately kitschy, and meant to look surreal – a chaotic remix of joy and despair. Well played.

What if jokes can, in fact, bring down governments? Can memes serve as strategic tools of counterpropaganda?Metahaven, Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? Memes, Design and Politics (Strelka Press, 2014). I’m unsure of the answers to these questions, but let’s reflect on some specific scenarios and ‘revisit the role of images in the functioning of political communication’.Noemi Biasetton, Superstorm: Design and Politics in the Age of Information (Onomatopee, 2024), 35. In the age of digitally networked propaganda that we live in, where political regimes co-opt digital platforms to blur facts and distort collective memory, memes emerge not merely as fragments of humour but as potent vessels of historical consciousness. Not all of them, of course, as we also just want to have a laugh and vent out our daily life struggles.

In this essay, I explore the concept of MEMEry (a portmanteau that describes the intersection of ‘meme’ and ‘memory’) as a vernacular, collective, and live digital archive composed of both appropriated still images (e.g., photography and illustration) and moving images (video and GIFs). However, these are not merely visual jokes or trivial content; they are performative fragments through which audiences process trauma, mock authority, and collectively remember. Though relatively underexplored as a concept, MEMEry was notably invoked by the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) in its exhibition Memery: Imitation, Memory, and Internet Culture.‘MEMERY: Imitation, Memory, and Internet Culture’, MASS MoCA, https://massmoca.org/event/memery-imitation-memory-internet-culture/. Mentions of memery outside that exhibition are limited to sporadic online wordplay jokes and some forums.

Memes act as photographic grenades – compressed bundles of cultural emotion and critique exploding across networked spaces. This reflection arises from a sublimation of MEMEry within my own practice, especially Tropical Trauma Misery Tour (TTMT), and develops through the Brazilian memetic wave that started as a digital collage during the 2024 Paris Olympic Games. What began as playful visual commentary quickly grew into a national and diasporic phenomenon, culminating in the promotional orbit of Walter Salles’s Oscar-winning I’m Still Here (Ainda Estou Aqui, 2024),A. O. Scott, ‘I’m Still Here Review: When Politics Invades a Happy Home’, The New York Times, 16 January 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/16/movies/im-still-here-review.html. intensified by the film’s leading actors, Fernanda Torres and Selton Mello, as participants in the meme’s recursive circulation.

PART II: OLYMPIC MEME REMIX OF NATIONAL TRAUMA

Before exploring the spontaneous viral memefication of I’m Still Here, it’s worth noting another spontaneous movement that took place during the 2024 Olympics. Although Brazil didn’t lead the medal table at the Olympics, there’s no denying that Brazilians excel in memes. One of the most iconic photos of the games, featuring surfer Gabriel Medina in a surrealistic pose, became a favourite among social media users, who ‘updated the image’ with each new Brazilian podium finish. It exemplifies both the humour and the symbolic significance of Brazilian national pride.

Memes, as explored in the Critical Meme Reader series published by the Institute of Network Cultures (INC) in Amsterdam, are never just ‘funny pictures’. They operate as cultural x-rays, revealing the fragmented and often contradictory fabric of the present moment.Chloë Arkenbout and İdil Galip, eds., Critical Meme Reader III: Breaking the Meme (Institute of Network Cultures, 2024), 12. At the intersection of global audiences and participatory culture, they become symbols onto which users project meanings, emotions, and political positions.Nasser Road: Political Posters in Uganda, ed. Kristof Titeca (The Eriskay Connection, 2023), 22. As they circulate, memes reshape interpretations of the figures and events they depict, constructing collective memory in real time, just as the viral image of the Olympic Games does. This is why memes often speak where other forms fall silent. Their humour is not always escapist but is strategically playful: they process trauma through punchlines, challenge authority through mockery, and critique ideology through exaggeration. Or just simply because they make you laugh.

Resolution, pixel count, or photographic ‘quality’ are irrelevant; what matters is the immediate, coded communication a meme establishes between image–text–viewer. Hito Steyerl, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, e-flux 10 (2009), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image. ‘When you find something that moves you emotionally or intellectually, there’s an impulse to pass it on.’Boot Boys Biz, interview in Unlicensed: Bootlegging as Creative Practice, ed. Ben Schwartz (Valiz, 2023), 205. As explored by researchers like Ryan M. Milner and Whitney Phillips, memes carry ideological weight as they can normalise fascism or ridicule it, amplify disinformation or satirise it into oblivion.Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner, The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online (Polity Press, 2017), 5–6. Their circulation is powered not by truth but by resonance (clickbait, hate clicks). What spreads is what sticks: anger, grief, glee, shame. It’s a dual act of archive and arena (call it arena as performance and/or battlefield as ideological warfare). It holds our emotional record while also becoming a battlefield for narrative control.Ryan M. Milner, ‘Media Lingua Franca: Memes, Media Ecologies, and the Polyvocal Public’, The Fibreculture Journal 22 (2013): 62–84, https://fibreculturejournal.org/wp-content/pdfs/FCJ-156Ryan%20Milner.pdf. Where hegemonic forces weaponise media to erase dissent, MEMEry retaliates with mockery, remix, and mnemonic resistance as ‘something new might come from within the constraints of the original’ as Ben Schwartz writes. ‘It’s a powerful gesture of transformation.’Ben Schwartz, ‘Under the Cover of Darkness’, introduction to Unlicensed: Bootlegging as Creative Practice, ed. Ben Schwartz (Valiz, 2023).

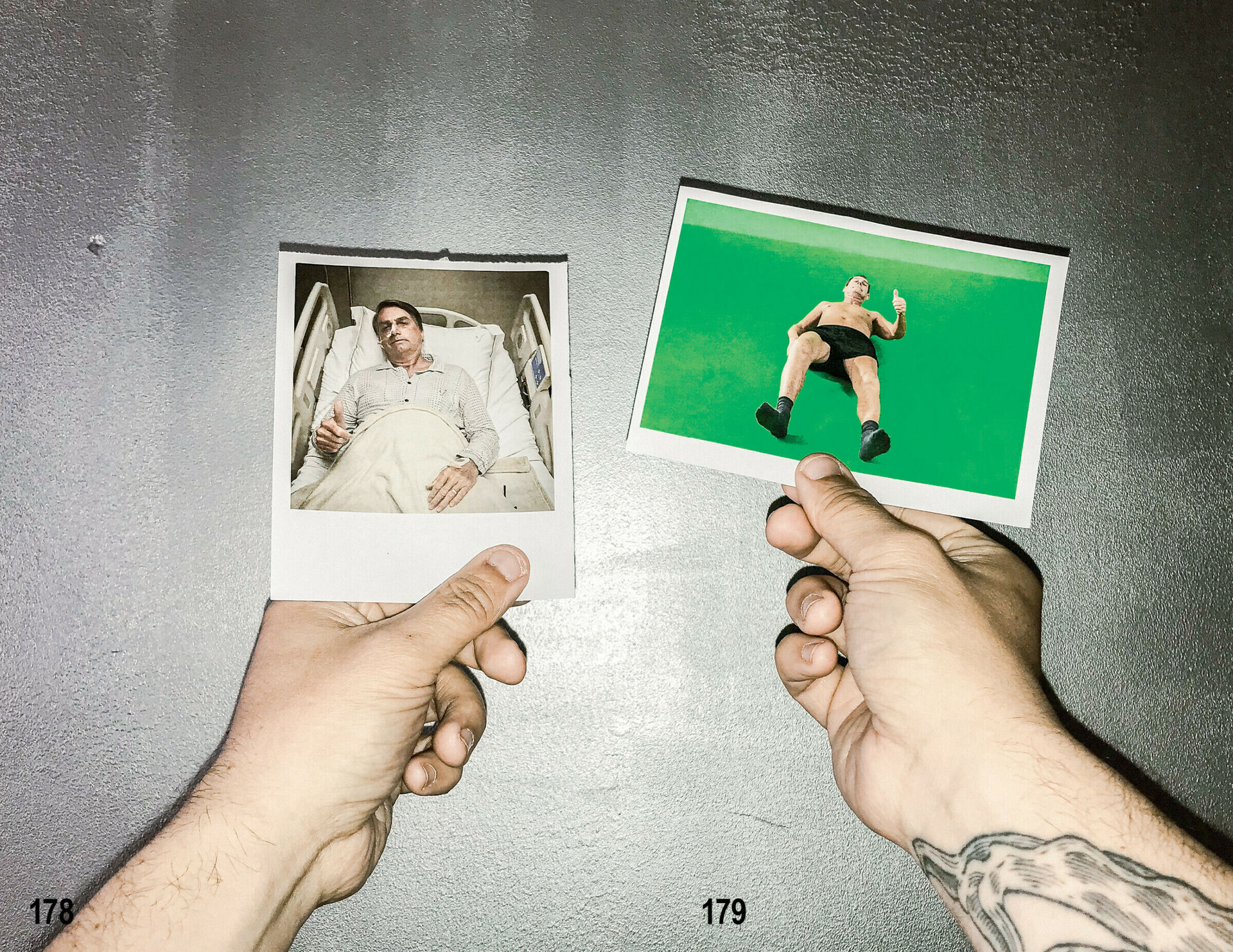

My project TTMT began as an attempt to visualise the collapse of truth in Brazil’s political theatre. Combining irony with national trauma, it reenacts former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s martyrdom strategy in the wake of his 2018 knife attack from various perspectives. What emerged was a project that moves between photography, video, performance, and editorial formats, borrowing from meme culture’s speed and irreverence to confront the networked violence of digital fascism/populism. Deep-fried images, overlaid text, and lo-fi absurdity merge into a kind of speculative campaign that mirrors the country’s chaos while laughing at it. Absurd becomes method; exaggeration, survival.

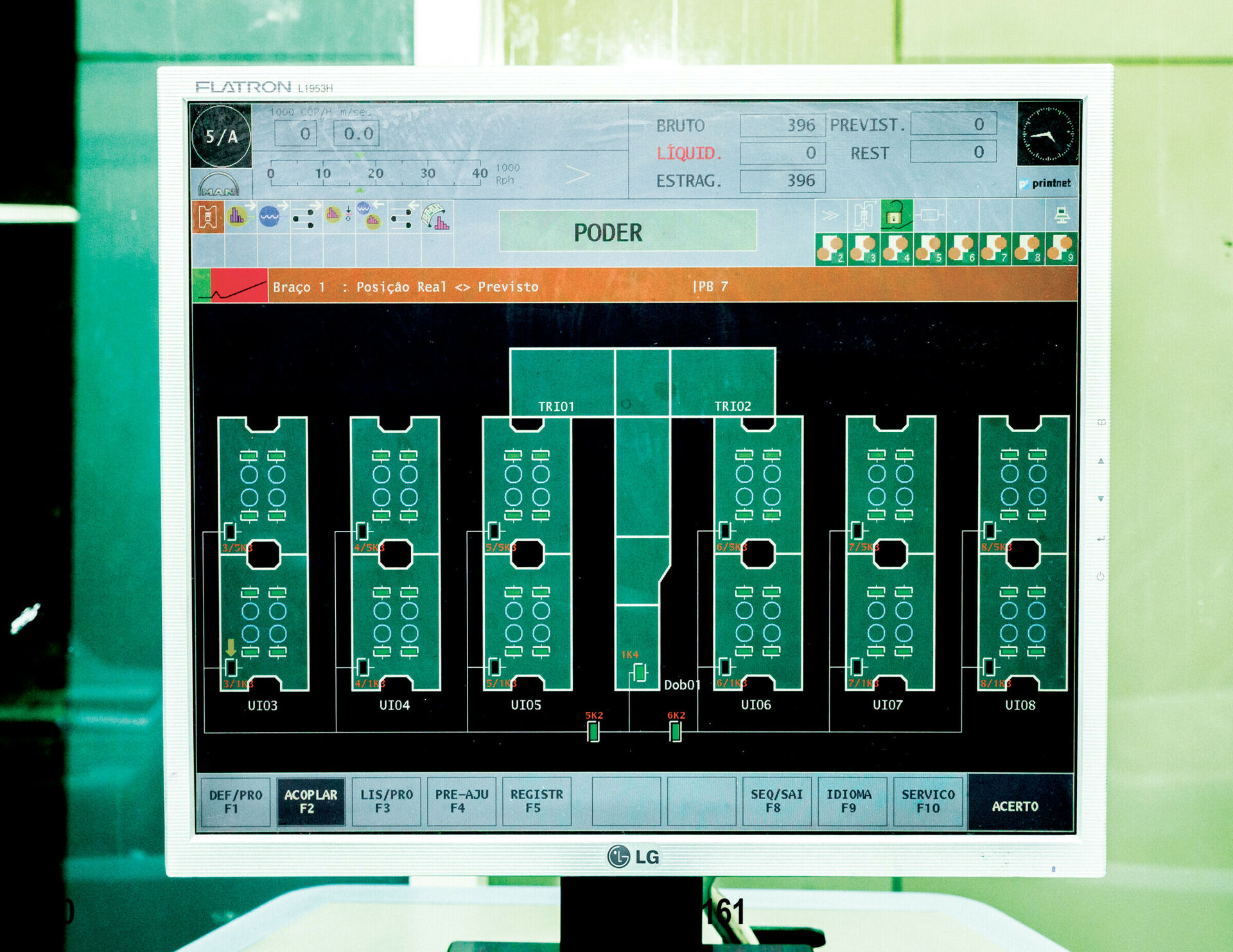

The Printing Power Media photograph sets the tone. Shot inside the printing press of Folha de S.Paulo, it captures the mechanical choreography of newspaper production – the repetition, the friction, the rhythm of power being literally pressed into existence. The word PODER (‘POWER’) circulates through rollers and ink, its meaning shifting from physical imprint to digital abstraction. The press becomes a metaphor for algorithmic distribution, echoing the disinformation machinery of Bolsonaro’s so-called Gabinete do Ódio (‘Hate Cabinet’) – an unofficial digital war room run by close allies and family members, where memes, rumours, and attacks were systematically crafted and released into social media feeds.

If Printing Power Media maps the architectures of communication, the video My_Sweet_President.exe exposes the performance that sustains them. The work reimagines Bolsonaro’s mythic self-sacrifice after the 2018 knife attack – a moment replayed endlessly online – transforming it into a dance of devotion and delusion. It stages a fever dream of populist spectacle, where politics is pure theatre and belief, an empty choreography on a green screen. At the centre of this spectacle stands an actor: a proxy president, both puppet and performer, trapped in an eternal loop of performance. His gestures are rehearsed until emptied of meaning. The dance, set to MC Poze do Rodo’s ‘No Baile Nós É Mídia’, turns the political stage into a dance floor where power depends not on conviction but visibility. The beat drives the movement – the movement feeds the image – the image feeds belief. As an echo. And then, there’s the green screen. Once a tool of illusion, here it’s stripped bare as an interface rather than a backdrop: a porous surface through which ideologies, fantasies, and desires are projected. By revealing the mechanics of its own construction, TTMT dismantles the aura of authenticity that populism thrives on. As an echo.

In a contrasting yet complementary gesture, the film I’m Still Here offers a cinematic extension of dictatorship memory work that privileges intimacy and narrative over irony. Adapting a book of family recollections from the Brazilian dictatorship into film, it transforms a personal archive into a collective experience, not through humour or digital virality but through cinematic depth, emotional resonance, and formal precision. Its impact lies not in MEMEry itself, but on the unfoldings of its cultural existence. It comes from memory as inheritance and resistance, connecting personal trauma to universal history through the sensory force of cinema. (As an echo.)

PART III: I’M STILL HERE MEMETIC WAVE

If a meme spreads by imitation, changes made in the process are still traceable when compared to an ‘original.’ Memes tend to be most successful if they get both copied and imitated.

– MetahavenMetahaven, Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? Memes, Design and Politics (Moscow: Strelka Press, 2014), 22.

A compelling illustration of MEMEry as both an affective and political force is presented in I’m Still Here. Chronicling the real-life story of Eunice Paiva, whose husband, former congressman Rubens Paiva, was abducted, tortured, and murdered by the military regime in the 1970s, the film revisits one of Brazil’s darkest, least reconciled historical wounds. What makes Salle’s film particularly emblematic of this essay's concerns, however, is not only its content but the memetic wave that surrounded it, transforming it from a cinematic event into a viral vehicle for remembrance and resistance in times of democratic turmoil.Associated Press, ‘In ‘I’m Still Here,’ a Family Portrait Is a Form of Political Resistance,’ AP News, January 10, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/im-still-here-fernanda-torres-walter-salles-518dd76570b83a97a69be78c15d80093.

The film’s release coincided with a period of acute political challenge in Brazil. The nation was grappling with the consolidation of far-right influence, the erosion of democratic norms, and a highly polarised public sphere rife with disinformation. Attacks on historical memory, particularly concerning the violent military dictatorship that took hold of the country between 1964 and 1985, were increasingly visible in political rhetoric and social media campaigns. In this charged environment, I’m Still Here assumed a dual role: as a work of historical reckoning and as a catalyst for civic reflection. In this climate, a film confronting that history was not just cinema but an emotional statement as well. It was political dynamite. Consequently, the memetic circulation on platforms like TikTok, X, and Instagram amplified this effect, transforming snapshots from the film and of its actors into viral moments. Like the Olympic meme, it remixed celebration, cultural pride, and a political opportunity against far-right narratives.

Despite a flash campaign of coordinated online backlash led by far-right influencers and political actors, the film gained enough momentum to win Best International Feature Film at the 2025 Oscars, placing Brazil’s unresolved trauma of dictatorship squarely on the global stage. Attempts to discredit the film, framing it as ‘leftist revisionism’, accusing it of distorting history, and even calling for boycotts and negative reviews on websites like Rotten Tomatoes and IMDb, had the opposite effect.Flavia Guerra and Vitor Búrigo, ‘Boicote a ‘Ainda Estou Aqui’ é vergonhoso e ignorante e não funciona,’ Splash UOL, November 20, 2024, https://www.uol.com.br/splash/noticias/2024/11/20/boicote-a-ainda-estou-aqui-e-vergonhoso-e-ignorante-e-nao-funciona.htm. In a digital Streisand effect, these efforts to suppress the film drew unprecedented attention to it, bringing it into mainstream debate far beyond the arthouse crowd. It’s a pixelated irony quite fitting for the times. I have my theories as to why, and they’re related to two of the leading actors: Fernanda Torres and Selton Mello.

Torres and Mello are two of Brazil’s most iconic actors, with careers spanning drama and comedy. While both have earned acclaim for their powerful, dramatic performances (Torres even won Best Actress at Cannes at age 19), they’re most cherished by Brazilian audiences for their comedic work in television and film. Torres’s expressive timing and vivacious characters in sitcoms like Tapas & Beijos (Slaps and Kisses) have made her a household name, while Mello’s versatility has led him effortlessly from television comedy to auteur cinema. Their performances evoke nostalgia and warmth, positioning them not only as performers but as cultural touchstones in Brazil’s media landscape.

Both actors are also deeply entwined with Brazil’s meme culture, not just as internet subjects with their media presence but as enthusiastic participants – ‘since he swapped cigarettes for meme addiction’,‘Selton Mello diz que trocou cigarro por vício em memes: ‘Bem mais saudável’,’ O Globo, December 28 2024, https://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/noticia/2024/12/28/selton-mello-diz-que-trocou-cigarro-por-vicio-em-memes-bem-mais-saudavel.ghtml. Accessed October 24 2025. Mello’s Instagram account has been filled with memes that share mundane frustrations and insane absurdities. Torres reflects frankly on this digital fame, saying, ‘I’ve survived with the young generation because I became memes. My memes in Brazil were like a fever.’David Canfield, ‘With I’m Still Here, Brazilian Icon Fernanda Torres Goes Global,’ Vanity Fair, November 26, 2024, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/story/fernanda-torres-im-still-here-awards-insider. One particularly beloved meme captures her unexpected reaction in a random airport interview, where she replies, ‘I feel like Pikachu’, a playful metaphor that quickly became a national catchphrase.Find the meme here: https://x.com/piresglony/status/1881452203493470211. Both Torres and Mello embrace this status with pride, describing memes as ‘a superior form of art’ while still identifying themselves as more than just a punchline. Their self-characterisation as ‘tragicomic actors’ in a ‘tragicomic country’ captures the complexity of Brazil’s political and emotional landscape, and why their image, both serious and satirical, resonates so deeply.

These layered personas (as tragicomic actors, later meme icons) played a pivotal role in the reception of I’m Still Here. Amid politically charged criticism and attempts to politicise the film, the presence of Torres and Mello provided a humanising and familiar anchor for audiences across divides. Their reputations, built long before the current era of polarisation, offered a bridge of affection and trust, allowing viewers to engage with the film on emotional rather than ideological terms. In essence, their comic legacy and cultural resonance contributed to the film’s success as a cinematic and cultural event, rather than just a political statement. Audiences not only saw actors portray the trauma of dictatorship; they also saw Torres and Mello act as bridges between past and present, history and humour, memory and meme.

An Xiao Mina describes this phenomenon as ‘memes to movements’,An Xiao Mina, Memes to Movements: How the World's Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power (Boston: Beacon Press, 2019), 18. where networked creativity becomes a means of mobilisation, a way to bridge emotional resonance and political action. In the case of I’m Still Here, memes did more than promote the film; they protected its message. Every reposted clip, remix, or ironic caption served as both an amplification and a shield, ensuring that the story could not be erased or silenced, even in an era of algorithmic suppression and state-sponsored disinformation.

The paradox here is that while I’m Still Here tells the story of an upper-middle-class family targeted by a brutal regime (highlighting the shock of state violence even against the privileged), it also invites viewers to consider the countless undocumented stories from Brazil’s working-class and marginalised communities, besides the ongoing possibility of falling into the same regime once again. The film’s selective lens becomes a mirror, reflecting the structural inequality in whose pain is remembered and whose is forgotten. Through its reception, however, the film catalysed a broader cultural reckoning. Native digital users, many of whom were born long after the dictatorship ended, began engaging with media testimonies, reposting related and in-depth material, and circulating infographics detailing the dictatorship’s abuses. In this sense, the film’s virality became a mnemonic wave, not unlike a digital wake, pulling submerged memories back to the surface.The On‑Set Memoir of I’m Still Here with Fernanda Torres and Selton Mello, YouTube video, 12:34, posted 4 February 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERYldY5lTIg.

The political valence of this virality cannot be overstated. While authoritarian movements have used meme culture to muddy facts, create chaos, and glamorise violence, I’m Still Here demonstrates how the same digital vernacular (memes, quotes, fan edits, online discourse) can reclaim historical truth and forge a sense of collective memory grounded in empathy.

PART IV: CONCLUSION MEMERY AS RESISTANCE

The film’s trajectory, from national release to global recognition, offers a case study in how networked audiences function today not just as consumers but as co-archivists, co-authors, and co-resisters. Yet it is also a volatile ecology, where reception is unpredictable and virality offers no guarantees. The political significance of this virality cannot be overstated. While far-right groups have long exploited meme culture to distort facts and glamorise violence, the spontaneous remix culture of I’m Still Here shows how the same visual language can promote empathy and remembrance. They alter, reframe, and defend meaning through sharing. In this environment, MEMEry is not just a static record but a live pulse: dynamic, abundant, and truly vibrant. ‘Memes live by echo and imitation.’Metahaven, Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? Memes, Design and Politics (Strelka Press, 2013), 34.

The evolution of the Medina meme during and after the 2024 Paris Olympics epitomises this rhythm of collective transformation. What began as a surfing image mutated through countless iterations, culminating in the unexpected appearance of Torres in an updated version a few months later – a remix amplifying both the humour and the symbolic weight of Brazilian national pride. In Viktor Chagas’s words, understanding the meme as a process, in a holistic view, allows us to grasp ‘the individual impact of each of these variants in the trajectory of the meme as a collective entity.’Viktor Chagas, ‘MEME-as-a-Process: A Phenomenological and Interpretative Approach to Digital Culture Items’, in Critical Meme Reader III, 72. Like a social life of images.

Brazil’s meme-scape (including Medina’s wave, Torres’s pose, and the cinematic echo of I’m Still Here) creates a visual network of digital fragments that merge the real with the absurd, transforming spectacle into critique. Repetition, replay, and echo serve as acts of remembrance. This looping, scroll-like, GIF-like temporality is where MEMEry is truly active. Its rhythm challenges fascism’s idea of permanence by emphasising motion, remixing, and play. It preserves memory through re-performance, turns trauma into irony, and defies oblivion with laughter.

My own works (Printing Power Media, My_Sweet_President.exe, and Tropical Trauma Misery Tour) trace this same cycle of repetition and disruption. Printing Power Media reveals the mechanical choreography of belief, where power is literally pressed into existence. My_Sweet_President.exe converts that power into artificial devotion: a deepfake choreography of political worship performed against the stripped illusion of a green screen. It’s faith made executable. And Tropical Trauma Misery Tour completes the cycle, transforming the remains of these images into absurd redemption – where humour and horror coexist, and the act of remembering becomes both chaos and critique. Together, they enact MEMEry as both method and resistance, a way of perceiving that accepts the fragment, the echo, the glitch. Resistance today may not emerge from clarity or solemnity, but from exaggeration, mimicry, and laughter. From repetition as revolt.

And so the question that opened this text – Which flavour of fascism do you want to live under? – returns, but this time, with a taste of poetic justice. Because, as of October 2025, Bolsonaro, the myth himself, has been sentenced to twenty-seven years in prison.Tom Phillips, ‘Brazil’s Bolsonaro Found Guilty of Coup Plot and Sentenced to 27 Years in Jail’, The Guardian, 11 September 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/sep/11/brazil-supreme-court-bolsonaro-guilty-coup. A headline that reads almost like a meme, circulated through timelines with the speed of vindication: the meme of his own tears now becomes a national punchline, a collective exhale after years of digital dread. Perhaps this is how history rewrites itself in the age of MEMEry. Not through solemn monuments or political speeches, but through loops of laughter that refuse to forget. Because to live in the loop is to remember. To remember is to remix. And to remix (sometimes) is the sweetest way left to resist.

Oh yeah, we’re gonna laugh. [send]

---

This article forms part of Networking the Audience, a themed online publication guest-edited by Will Boase and Andrea Stultiens, developed in collaboration with MAPS (Master of Photography & Society) at KABK The Hague. The contributions emerge from an open call shared across the MAPS network, including alumni, and bring together artistic and critical perspectives on photography, publishing, and circulation. Together, the nine contributions reflect on how digital systems reshape authorship, readership, and meaning-making, foregrounding publishing itself as a creative and relational practice. Rather than addressing a fixed audience, the series explores how images and texts move through fluid, networked publics.