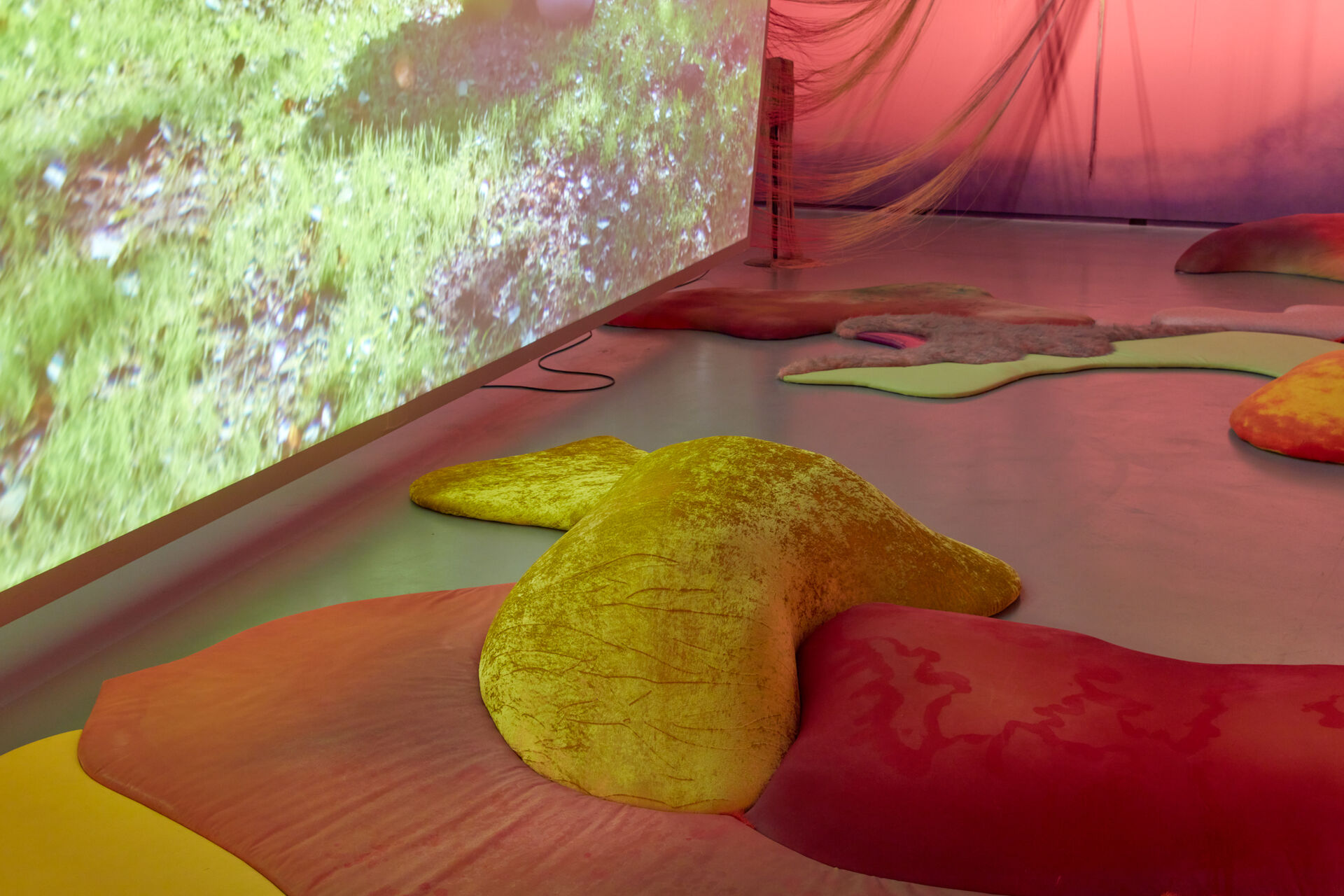

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

melanie bonajo: Ecologies of Compassion

Editor's note. From 17.02.2023 to 04.06.2023, melanie bonajo’s immersive video installation When the Body Says Yes is on view at FOMU. This was the work with which bonajo represented the Netherlands at the 59th Venice Biennale (2022): an exuberant film and installation about the liberation of the body in our relationship to each other and the world we inhabit. The presentation was curated by Orlando Maaike Gouwenberg, Geir Haraldseth and Soraya Pol and shown in a small church off the beaten track of the Biennale. On this occasion, Ilga Minjon spoke to bonajo in a conversation that unfolded across all possible digital media.

Ilga Minjon

14 apr. 2023 • 12 min

Dear Friend, Thank you for your e-love, much appreciated. My group-self, as an ecology of impulses, needs a bit of time to answer all your precious words, we follow the cosmic clock. Please make sure to practice your PC muscles for world peace, ending all systems of oppression and increasing interspecies love while waiting for an actual reply; may you feel loved, orgasmic, rested, nurtured and fully alive. Automated email response from bonajo

Anyone who emails melanie bonajo, despite their announcement that you’ll have to wait for a reply, receives an immediate introduction to the somatic sexologist, intimacy coach, artist and self-proclaimed hyperelf. And although they sometimes feel like retreating indefinitely into a fairy-tale forest, in the run-up to the Venice Biennale it’s almost impossible to maintain a cosmic approach to time. But even when the Biennale soon opens, it won’t be the final stop – ‘more like a psychedelic roller coaster’, says bonajo. ‘Or a stop along a journey’, a journey much larger than this institutional context or even the artist, and one that has long begun.

In 2022, the Dutch pavilion in the Giardini was handed off to Estonia on a one-off basis. For this reason, bonajo’s work was displayed in the Chiesetta della Misericordia, loosely translated as ‘little church of mercy’: a former scuole and abbey church with a turbulent history. In a society without healthcare institutions or social safety nets, places like this were the first hospitals, providing care for the poor and organising shelter for those excluded by the hierarchies of their time. As a port city, Venice was hit exceptionally hard by epidemics over the centuries. In the case of this abbey it would even bring about the downfall of the last remaining order of Augustinian friars: the entire population of monks there dies from the Plague in 1348. The church passes into the hands of patrons who replace, sell and later neglect its contents, including the original paintings, until the abbey is secularised in 1973. ‘And now we come flying in, on our broomsticks,’ laughs bonajo.

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

Embodied leadership

The focus of bonajo’s practice is embodiment, more specifically the embodiment and translation of values and beliefs. In the field of somatics, or bodywork, the body is viewed as an intelligent source of information that stores – and is able to express – stories and experiences. Somatic work starts from the belief in the intrinsic value of every body and aims to align our thinking, feeling, experiencing and doing. Enter politics: embodiment also implies extending the implications of your values, and thus contains a societal and social component. To embody your ideals is not a cognitive, rational or policy-encoded matter, but a process and a commitment to interconnectedness and self-reflection, a willingness to carry through on your beliefs. Even if that process is slow and sticky.

In an email, bonajo writes: ‘This shared, radical dependence or kinship forms a web of interrelations where it’s impossible to say exactly where "I" end and the "other" begins, because my existence is manifoldly intertwined with the existence of another. Capitalism despises Nature, the body, animals, womxn, Indigenous people, etc.‘womxn’ is an inclusive term that brings cisgender and transwomen under one word. Under capitalism, everything is turned into an industry in which our body, our doing or thinking is converted into revenue. Unity, care, friendship and a return to the body can be seen as a defiance of a system that hinges on profit.’

bonajo, assigned female at birth, identifies as non-binary. As an artist, they’ve been questioning traditional divisions for years, with their multifaceted, personal and colourful practice that spans photography, film and installations — often based on intimate participation or long-term collaborations. Works like Night Soil Trilogy (2014-2016), Progress vs Sunsets (2016) and Progress vs Regress (2017) challenge oppositions such as public/private, people/things, isolation/intimacy and Nature/technology, and garnered bonajo a nomination for the Prix de Rome.

These traditional divisions are evidently also political. The rise of capitalism was made possible by relegating womxn and people of colour as inferior, and subordinating the human body to the mind in the service of productivity. It’s here that social hierarchies find their cause as well as their effect. Think of ableism [discrimination on the basis of perceived (bodily) capabilities, ed.], misogyny, transphobia, racism and other forms of othering.

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

One of the obstacles to structural elimination of inequality in practice, is the fact that those with the most decision-making power often have the least lived experience of exclusion, yet they have internalised the idea of their own objectivity and neutrality. When you’re cycling and the wind is in your back, it’s easy to think there’s no wind at all. The upshot is that while there are plenty of lofty ambitions around ‘diversity’ and inclusion nowadays, it's rare to see embodied policies actually implemented.

The art world is not exempt from these systems, although it maintains a stubbornly progressive self-image. Four years ago, a growing dissatisfaction with this state of affairs lead bonajo to move Berlin and to begin training as a somatic sex coach. They shift the focus of their imagination and expression from visual art to activism and social organising, where embodying your ideals is central to the work. As a sex coach, bonajo experiences at first hand how societal structures such as inequality and a lack of knowledge about it affect our bodies. But also how these can be healed.

Politics is a guiding force in the decisions they make. ‘But love transcends everything: that’s what I really learned during the pandemic. Even if I have to remind myself sometimes. Like when you deal with harm and trauma caused by others. That’s incredibly difficult. My goal is to continue to approach it from a place of compassion, to refuse to lose sight of someone’s humanity, in all its complexity. We’re all trapped in the system that created us.’

Bodily connections

The artist, the activist, the healer – bonajo brings all these archetypes with her to the Church of Compassion in Venice. At first glance, When the body says Yes is a playful, cinematic presentation in four parts in which many bodies claim space, next to and with each other. Bodies touching, caressing each other, celebrating pleasure and intimacy, exploring their genitals, role-playing, seeking closeness. Above all, bodies feeling free, unashamed and whole. In part because the representation of bodies that do not receive this kind of attention and respect in the media or in (art) history, this approach is quite refreshing. And possibly subversive.

A guiding motif in the work is the importance of consent. Derived from Latin, consent originally means more than just the expression of permission or approval – it is ‘feeling together’. Because of social hierarchies, most of us are simply quite ill-equipped to feel together, or even to empathise at all. ‘But how do we learn to express our desires while respecting the personal boundaries of others?’ asks bonajo. The title, When the body says Yes, refers therefore to a somatic exercise that is meant to make you aware of how you physically experience an intimate situation.

bonajo writes via Telegram: ‘Most people don’t know what an authentic "yes" feels like in the body. With sexual intimacy, it’s only possible to feel an embodied yes, in connection, when you feel safe. Safety means not just the absence of a threat, but also the experience of a connection. Hearing a "NO" means you need to acknowledge the other (mostly cis/trans womxn, transgender, queers, BIPOC, nonhuman animals, Nature) as someone with their own needs and desires, and that! THAT works, listening and presence, that can feel very uncomfortable for those with privilege and entitlement. It’s often said in revolutionary movements: For people used to privilege, equality can feel like oppression.’

Current events catch up with these themes when, as during the Corona pandemic, we are thrown into a global state of physical isolation and are forced to communicate mainly by digital means. The increasing digitalisation of our relationships had already made bonding through physical contact less self-evident — the pandemic made it a downright risk. For bonajo, this all connects to a central concern: 'Is touch a dying sensation?' Loneliness seems to be the epidemic of our time. We seem to be losing the language of our bodies. Why do we teach children to communicate only verbally and not to feel with their belly? What does a lump in your throat tell you? Our spoken language reveals wisdom that originates in our bodies. But how can we learn to listen? By exploring your own boundaries, you learn what you need, even if that's just a hug. To give yourself that opportunity – what we do and don’t want in our lives – is a very loving way of being. ‘It is the place where intimacy thrives, when we know when our body says yes. :)’, they write in an email.

What does this look like in practice? For a hands-on approach, bonajo points to the Berlin-based collective The Skinship, with whom they organised an online workshop series on guided self-pleasure during the lockdown, as a tool against the isolation and growing sense of doom that many were experiencing.The Skinship organises workshops in Berlin and elsewhere on a fairly regular basis. Information via instagram: @skinship_berlin. The aim was to provide an alternative to the tendency to spend too much time online or on exploitative porn sites, by giving participants a deeper experience of intimacy with themselves, with a focus on queer and non-normative bodies.

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

Hypervisibility

bonajo's proposed campaign image for the Biennale, Big Spoon, showing a large group of people spooning, was rejected by the city of Venice and on Instagram on grounds of showing too much nudity. It frustrates bonajo: ‘The film is about maximising intimacy and surrendering to sensuality, without sexuality. It's not even about sex. In our society, sexuality is used everywhere to lure people into experiences that have nothing to do with sex. In my film, sexuality is a teaser to a space where we’re actually negotiating intimacy, touch, the body, feeling and connection.’

It's bonajo goal to create a kind of transformative cinema that embodies these values and beliefs on all levels. Not only in terms of visibility and representation, but also behind the scenes: ‘How do you treat people, how to deal with conflicts, with your crew, finances, pay. Of course, I’m also aware of how my own privileges shape my role and the spaces I work in. That can be very complex. For a long time, leadership has been based on power over, rather than power with. So I started learning a lot about non-oppressive and embodied leadership. People who take the lead in a social group are sometimes more motivated, or capable. If you want to lead, you have to get people behind your vision for the collective. Leadership then becomes a kind of service position for the collective.’

bonajo hopes that visitors to the presentation in Venice in 2022 – and the one in Antwerp in 2023 – will recognise themselves in the complexity of self versus other and that through these points of recognition, they will be able to transcend their own assumptions. ‘That’s my biggest drive, how can we get rid of this othering? How can you recognise the other as a mirror of your own human journey?’

Those familiar with bonajo’s earlier work will likely notice that this focus is less a new direction than it is an extension of the love-centred and body-oriented questions that they’ve been exploring in other forms for some time. bonajo: ‘It’s all about the values you hold in your relationships and towards yourself. How can you keep exploring yourself like a map? Unlearn your own inner prejudices? To continue to work within my visual language is just another place on that map, where I constantly apply different skills.’

bonajo liked being able to present in the Church of Compassion, because it feels as if the building is an embodiment of something bigger, something in awe of Nature. ‘That allows me to rediscover a connection with myself in it, despite its patriarchal, Christian origins. The space, the angle of the light. It’s really a temple that was meant to be experienced physically. The Rietveld pavilion obviously wasn’t built with that in mind. And at the same time we’re standing there with everything that god forbids, like, we are the daughters of the wxtches you didn’t burn, motherfuckers!’

In such a context, to honour, reclaim and make hypervisible the human bodies that historically have been erased was extra special. It underlined bonajo's mission: ‘It’s precisely by cultivating new ways of being in our own bodies, that we can radically change the way we interact with others.’ Even in this traumatised building – originally an ode to our capacity for humanity – the process of healing can get underway, to the chimes of the cosmic clock.

melanie bonajo’s reading tips for an optimal experience of When the body says Yes, and of your own body

- Rupa Marya en Raj Patel, Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Justice, 2021.

- adrienne maree brown, Pleasure Activism, 2019.

- Staci K. Haines, The Politics of Trauma. Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice, 2019.

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self Love, 2018.

- Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Mending of Our Bodies and Hearts, 2017.

- Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation, 2017.

- Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma, 2014.

- Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, 2004.

- bell hooks, Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, 2000.

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 1999.

- Janet W. Hardy en Dosie Easton, The Ethical Slut, 1997.

This article was published in Metropolis M's Special Biënnale Magazine in April 2022 and was edited and translated by Ezra Babski for the presentation at FOMU. When the body says Yes is on view at FOMU, Antwerp, until 4 June 2023.