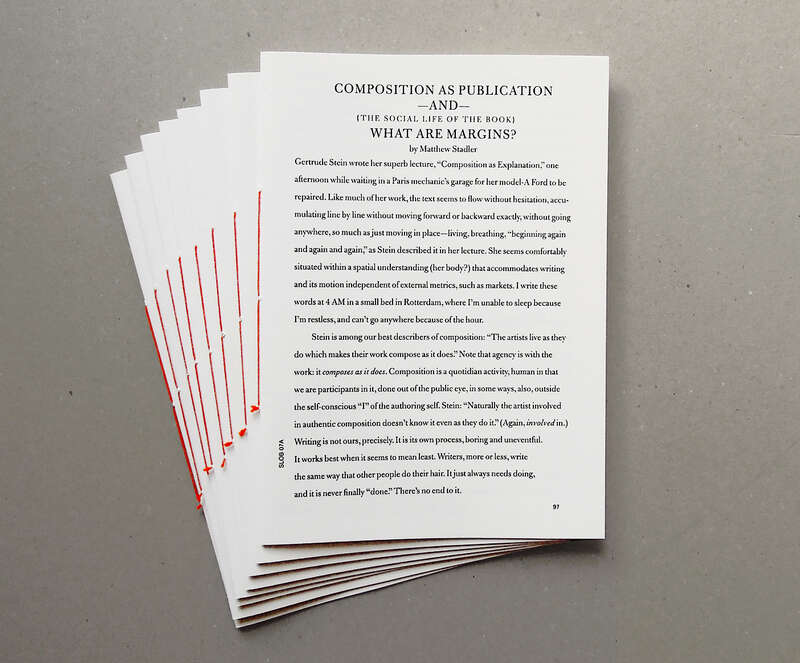

I received this publication a week before moving house and am grateful that it found its way to the top of a box. Its form (small, saddle-stitched signature with black text on white pages) seemed a manageable way to begin reading again after a period of disruption. The fact that I’d likely lose it if I put it on the bookshelf helped too, lending an energy and urgency to the first reading. I remember nothing of the haptic or visual experience – only a sense that I had begun talking with Stadler. I have continued since. The conversation I’ve managed to maintain in my mind is a result not only of resonance with my own beliefs but also direct challenges to some of my assumptions and hunches. These sixteen pages asked questions of my work and area of study (the photobook) with an intensity at odds with their unassuming appearance.

In Composition as Publication, Stadler explores the relationship between composition (‘a quotidian activity’) and publication (‘the other half of the writer’s life’) via margins, marginalia, and market commodification. There is no mention of photobooks or photography – a significant benefit to thinking about the process and possibilities of this specific medium without the burden of established and expected references. I find myself imagining what Stadler would make of the scarcity and commodification that are so central to the photobook market. I wonder what marginalia and counter voices are visible alongside the page-based photograph, and I’m mulling how the dominance of book-as-output and maker-centric discourse curtails a playfulness in publishing as a holistic and strategic act.

Note to the reader. This article is part of Trigger’s 2023 ‘Summer Read’ series. We invited writers, researchers, photographers and curators to share what is currently occupying their mind through one publication they have been (re)reading during summer. What matters to them is now being recast as a challenge for today. Highly personal entries to a diversity of publications (photobooks, studies, monography, essay, historical research) lead us – readers of these readers – to reorient our gaze on (the history of) images and photography.