Mark Neville in conversation with David Campany

For the book Fancy Pictures – Mark Nevill (published with Steidl, 2016), David Campany had an extensive interview with Mark Neville (UK, °1966). On the occasion of EXTRA #21 a shortened edit was published in Dutch. On the occasion of TRIGGER #1 – Impact we decided to republish this edit in English. Neville’s photographic practice refocuses the interest of the impact of artistic work for specific audiences in certain communities. His ‘fancy pictures’ are the result of his urge to know ‘how a community in, say, a working-class shipbuilding town might respond to photographs I made with them’. Though explicitly not made for an art world, the museum and gallery world became much interested in Neville’s The Port Glasgow Book Project.

David Campany

04 mrt. 2020 • 10 min

Shore Street Bus Stop, 2004

How did you come to the very distinctive kind of approach in your work? Much of it involves you figuring out a relation to the world, how to negotiate it.

Absolutely. My work is intensely personal. Many artists strive to make a separation between their personal life and their work but I can’t do that. It’s not obviously autobiographical, but I am aware that every time I embark on one of my projects it involves me living with a community for quite a long time, becoming part of that community. It’s a search, although I’ve only come to figure this out recently, for a sense of belonging, a family, and quite often one finds very strong family units within working-class communities. There’s a desire to be accepted as one would be by a family, and a desire to mediate that relationship somehow, which is always a negotiation, a collaboration, as opposed to an objectification.

Coronation Park, August, 2004

You decided at a certain point that there was something in the documentary approach, although you have serious problems with the conventions and assumptions of mainstream documentary.

Generally speaking I wasn’t getting much of an audience, despite my best efforts. I carried on making work, in a very committed way, but I was not represented by a gallery and I was not showing much at all. Soon I began to ask for whom I was making the work. Who was I trying to communicate with? Who was my audience? While some of my work had a visceral visual quality, it was quite clearly for a knowing art world familiar with the references. I got very frustrated with that. Could I think about a different audience and maybe let that inform or direct the work? So my biggest jump was from thinking of the gallery or museum as the ultimate audience to thinking “isn’t it more interesting to find out what other communities and audiences think about work that is for them, but also challenging for them?” I’d done enough art school theory, and I was as well-versed as anyone in the arguments about audiences, but none of those arguments could tell me how a community in, say, a working-class shipbuilding town might respond to photographs I made with them. I was really excited about what might be possible.

How did The Port Glasgow Book Project came about?

I was 34 or 35 years old. I was living in Belgium but moved to Glasgow in 2001. I saw an advertisement in an art magazine inviting proposals for a “public art” project on the west coast of Scotland. It didn’t specify anything more than that. It was a totally open call. I had discovered Port Glasgow, which is up the coast from Glasgow. I loved the place immediately. It’s a former shipbuilding town, full of character, visually stunning, with a great view out to sea. Only one shipyard remains. It was hanging on to its former glory. In the 1950s more ships were built in Port Glasgow than anywhere in the world. Now it’s clinging to a post-industrial identity.

Greenock Sports Personality of the Year Award, 2004

And what was your public art proposal?

Well, it had to be something that was available to the whole town. I remember being in a bookshop that had a large photography section, looking at expensive coffee-table books of social documentary photography. I would sit down and look through these things. It struck me immediately, and amazingly clearly, that these books were not aimed at the kinds of people who were in the pictures. That seemed wrong. They were images of poverty and hardship made for comfortable people. It made me feel awkward but I was fascinated looking at this material, packaged nicely in glossy, hardback books. I got very interested in how those kinds of images are disseminated. There was a real contradiction, a hierarchy, an exploitation. From my art school background I had been very interested in artists thinking about context, people like Hans Haacke who has made many works that addressed or critiqued something of the institutions in which they were presented. Could I extend that idea of “institutional critique” to social documentary photography and, indeed, books and book selling? So the idea was to produce a book about Port Glasgow that was directly for the people of Port Glasgow. I would be the photographer but I would give as much authorial control as I had to the community. I would ask them what I should photograph. I would ask them to collaborate. Even to help me make costumes. I would shoot in a mix of black-and-white and colour. And I would make the book only available to people who lived in the town. I would print eight thousand copies: one for each household. The book would never be commercially available. It would never be in the bookshops where I had realised what was so wrong with social documentary photography. These coffee table photo books always end up on the coffee tables of white, middle class people like me and not on the coffee tables of those communities they represent.. I wanted to challenge that.

And your proposal was accepted. That was brave of the decision makers!

Yes, it was really brave.

What was the budget for The Port Glasgow Book Project?

The total was £106,000. Once I’d been told my concept was approved, I worked out the budget and it was accepted.

This was very unlike the conventional “public art” project…public sculpture, billboards, a mural, or performances. What you were proposing really hadn’t been attempted before.

Yes, I thought of the book as a sort of symbolic gift. The people of the town might like it, or not like it, but it was a direct return of something to them. Unlike a bronze sculpture in the town centre, they had control over it; both in its creation, and as an object when it was complete.

Coronation Park, 2004

This was the beginning of you really immersing yourself in a community for a long period of time, something you now do with nearly all your projects.

I was ready to do that. I had already cut quite a lot of ties with the art world. I wasn’t following it. I wasn’t going to gallery openings. I was completely ready for a new approach. I had a budget and I could really try a new way of being, living, working and making images. I gave myself two years to focus just on this project. I got to know lots of people in the Port, developed new relationships. I found that if you show no fear, if you are honest and open about what you’re doing, it’s fine. But in a tight community, where everyone talks to everyone, if you upset someone, you upset everything.

Did people see the pictures as your project progressed?

Yes. I had small exhibitions throughout the two years. I paused every month or two to show what I was doing and have an exhibit in the window of the butcher’s shop. And when I was ready to print the book I showed my whole edit and asked if anyone objected to anything. That was very important.

Your photography is enormously ambitious technically, pictorially. Some of your pictures fi t with what we would recognise as social documentary but there are also staged moments, there is very elaborate lighting, the black-and-white / colour switch, you even use a sports photo-fi nish camera. Is all this an attempt to disturb the expectations around how certain subjects “should” be photographed?

Absolutely. Disturb the expectations, break the habits, disrupt the conventions.

But without losing the impulse to make richly descriptive photographs…

Right. I want people to be able to see the conventions but also to be able to relate to the photographs as documents of some kind. To do that you can’t be complacent or lazy or unambitious. I had to attack on all sort of levels. So yes—different cameras, different kinds of collaboration, different kinds of lighting and composition.

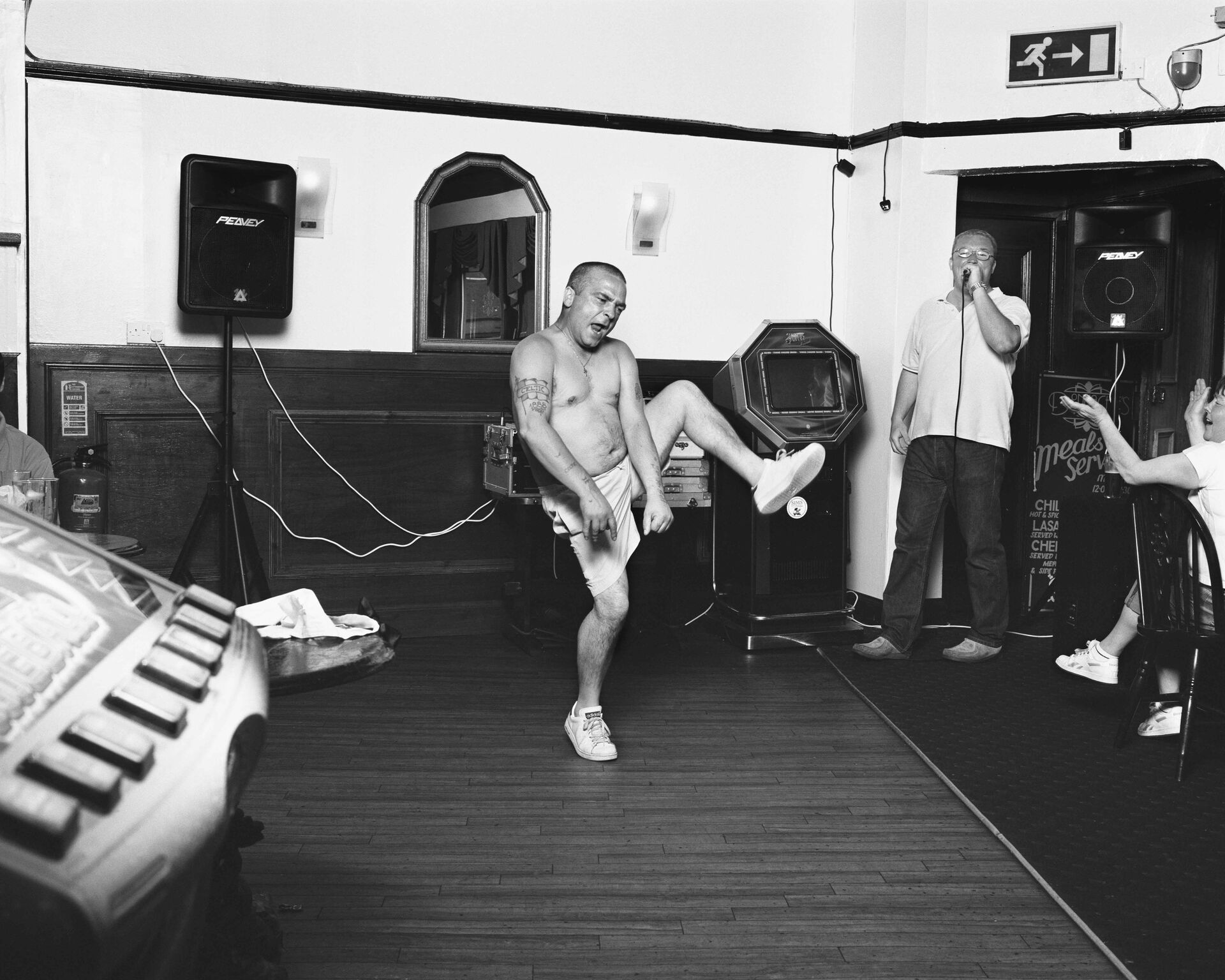

Bar of Donnachie, 2004

How long did you shoot for this whole project?

Just over a year. I came up with an edit and a design, and got it printed. All eight thousand copies. After much bureaucratic struggle I got permission to allow the local boys football team to deliver the book. That way I could give them, instead of Royal Mail, the £14,000 that I had budgeted for postage. Whenever possible I wanted to feed back into the community, and this idea fitted beautifully, both ethically and conceptually.

How did it feel seeing the book in the hands of the people of Port Glasgow?

It was one of the best days of my life watching these swarms of kids chapping on doors of the council estates and handing over the books.

Were you nervous? Although you had been collaborating all along it was, in the end, a book with your name on it and you were taking responsibility for it.

I was exhausted by then. It had been a long, long process. The first people to see it were the staff at Port Glasgow Town Hall, where I stored the book (and where I had photographed people dancing). I was petrified. But actually they liked the book and were really pretty proud of it. And I think they were shocked at how high the production values were, and how substantial it was. I don’t think they were quite expecting to see themselves historicised in a big, hardback book, and in such a respectful way. And all this was new experience for me. I didn’t know what to expect.

I guess nobody did. It’s not like any other project.

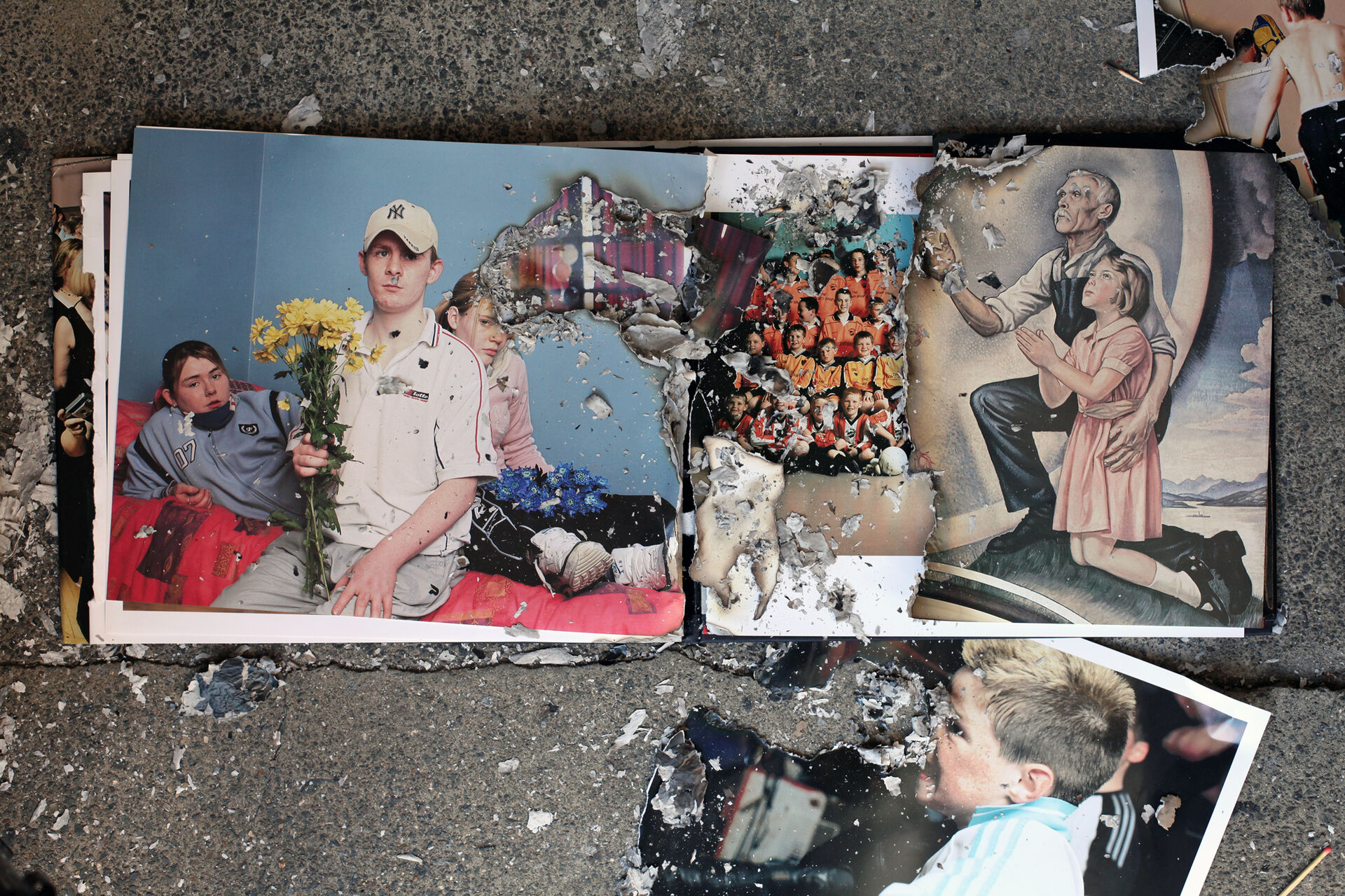

Right. But in a way that was what I had been seeking. Not everyone liked the book. The most extreme reaction I had was from the residents of Robert Street, who had a meeting and decided there were too many photographs taken in Catholic pubs and clubs and not enough taken in Protestant pubs and clubs. It’s still a sectarian town in many ways. They decided to burn their copies of the book. I literally got a call from the fi re station telling me a pile of my books was on fi re. I looked at the book again: there were nine photos taken in Protestant pubs and clubs, and seven in Catholic pubs and clubs.

Betty at Port Glasgow Town Hall Xmas Party, 2004

That slight imbalance hardly justifies a book burning.

Now I see it as an interesting thermometer of religious feeling and social tension. At the time I was just upset.

That was a very intense project. And I imagine, while you learned a lot, the conclusions you could draw were complicated. That said, it’s clear you felt that this immersive way of working and then giving back had great potential, and that the visual approaches you had begun there could be developed further.

Yes, but in a way the project was so specific to that community that I didn’t have much to show for it afterwards. It had been made and consumed entirely in Port Glasgow and now it was over. I did keep back a few copies of the book. I sent it to a handful of art world people and sent one to you, as I liked your writing and thought you would understand what I was doing, although I didn’t know you at the time.

Port Glasgow Boys Football Team who delivered all eight thousand copies of the book to each home in the town, 2004

I remember you sent the book with a note saying: “Dear David Campany, this book is not for you.” It was a strange feeling looking at it because, as you say, it was a closed project. It wasn’t “for me” or anyone else outside of the town, at least not in the primary sense.

But, paradoxically, it was precisely because the project was so closed that the art world got interested in it! The perversity of human nature. Museums and galleries wanted to make the work the subject of exhibitions. Also the book began to get a wider reputation and copies starting selling on eBay, sometimes for up to £500. So if you hadn’t burned your copy you could sell it. The book cost £12 per copy to make, so that is quite an increase!

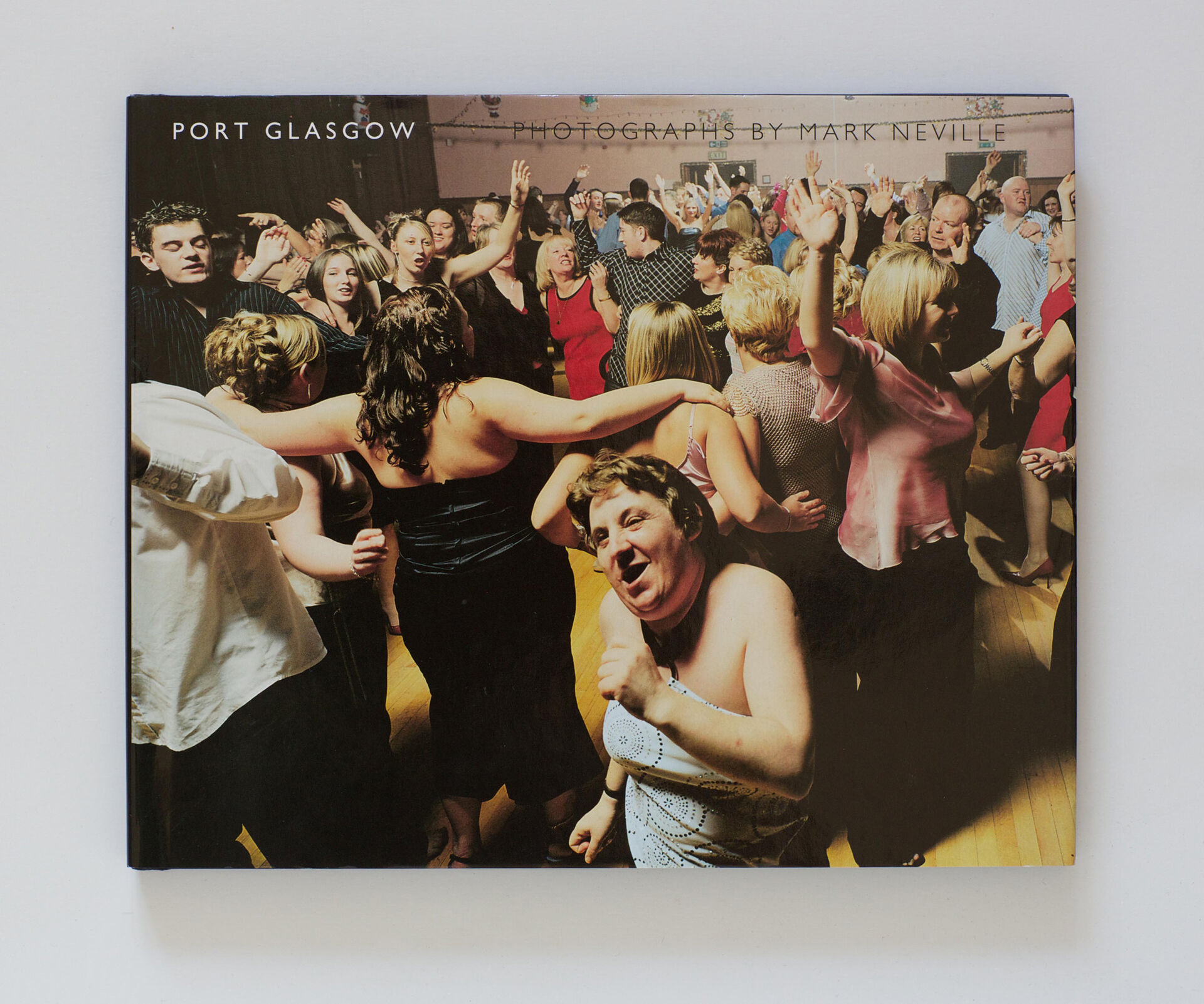

Cover of Port Glasgow, 2004

Copies of Port Glasgow burnt at the back of the Hibs Club, 2004

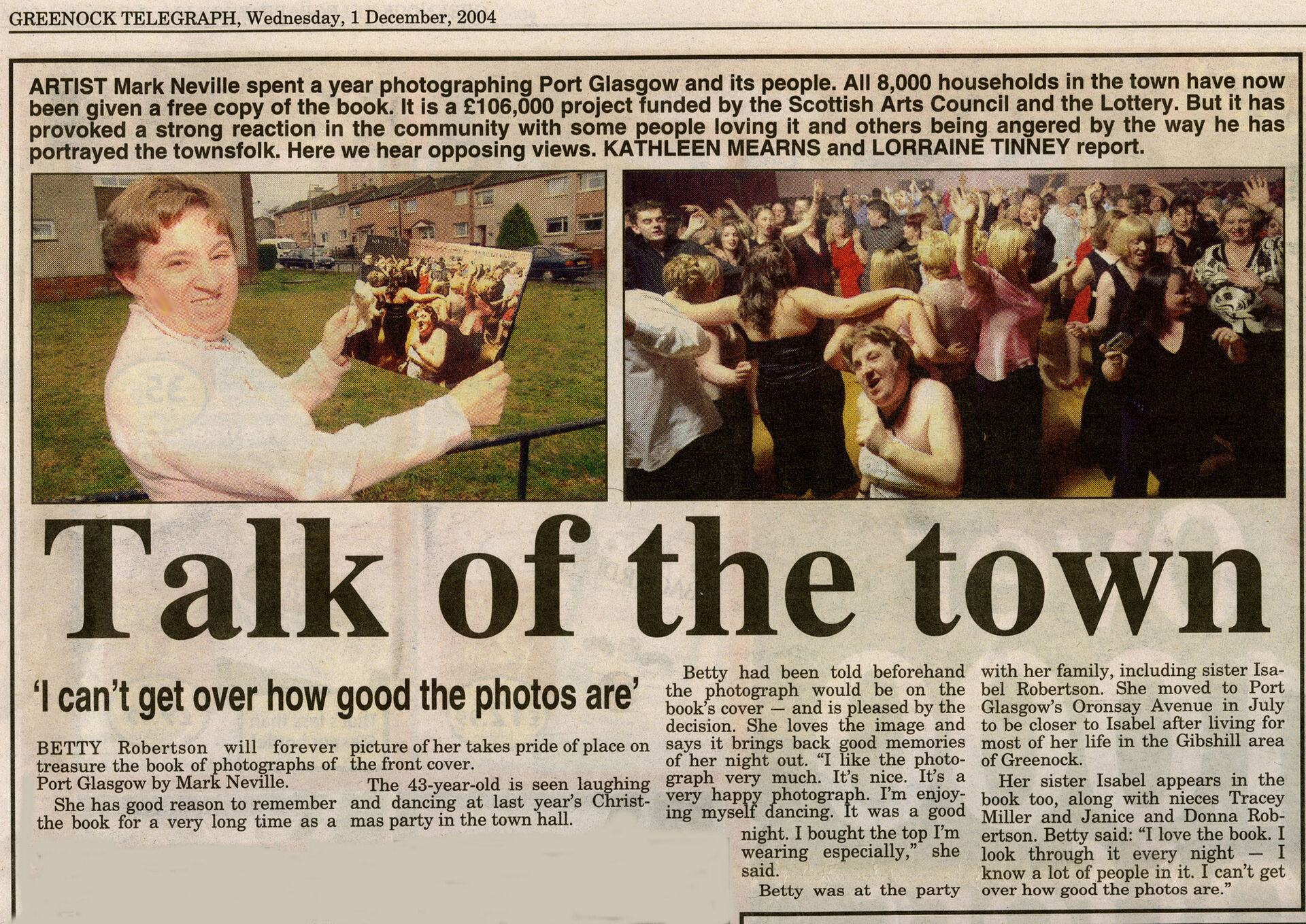

The Greenock Telegraph, 1/12/2004

The art world interest is significant because, of course, within that world there has been a renewal of interest in experimental documentary work.

Well, I’ve tried to continue with the attitude that the art world is only ever a secondary audience, even though secondary audiences are important.

It comes down to a real split in documentary and campaign work, between sticking to conventions and trying to find new approaches. On the one hand there is the notion that there is a set of tried and tested conventions; on the other a there is Bertolt Brecht’s conviction that “realism must be sovereign over all conventions” because the world is changing so fast. Finding the right form for what you want to say is a struggle and it must come out of an engagement with the subject. There is no pre-packaged, guaranteed convention. Experimentation is a necessity, not an artistic indulgence.

My feeling is that the door to experimentation should always be left open.