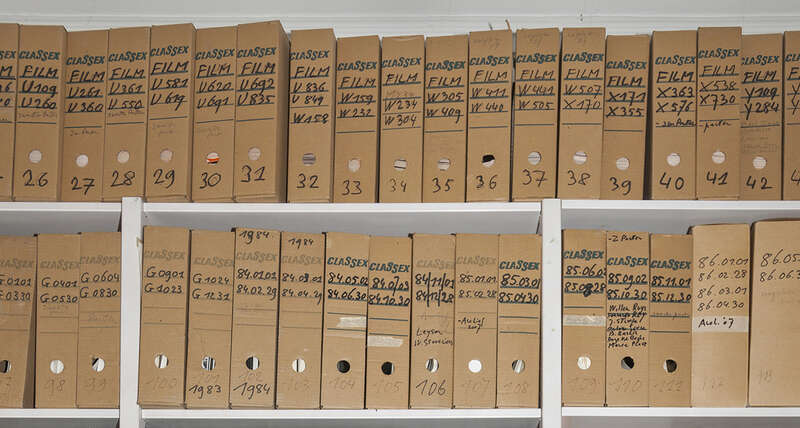

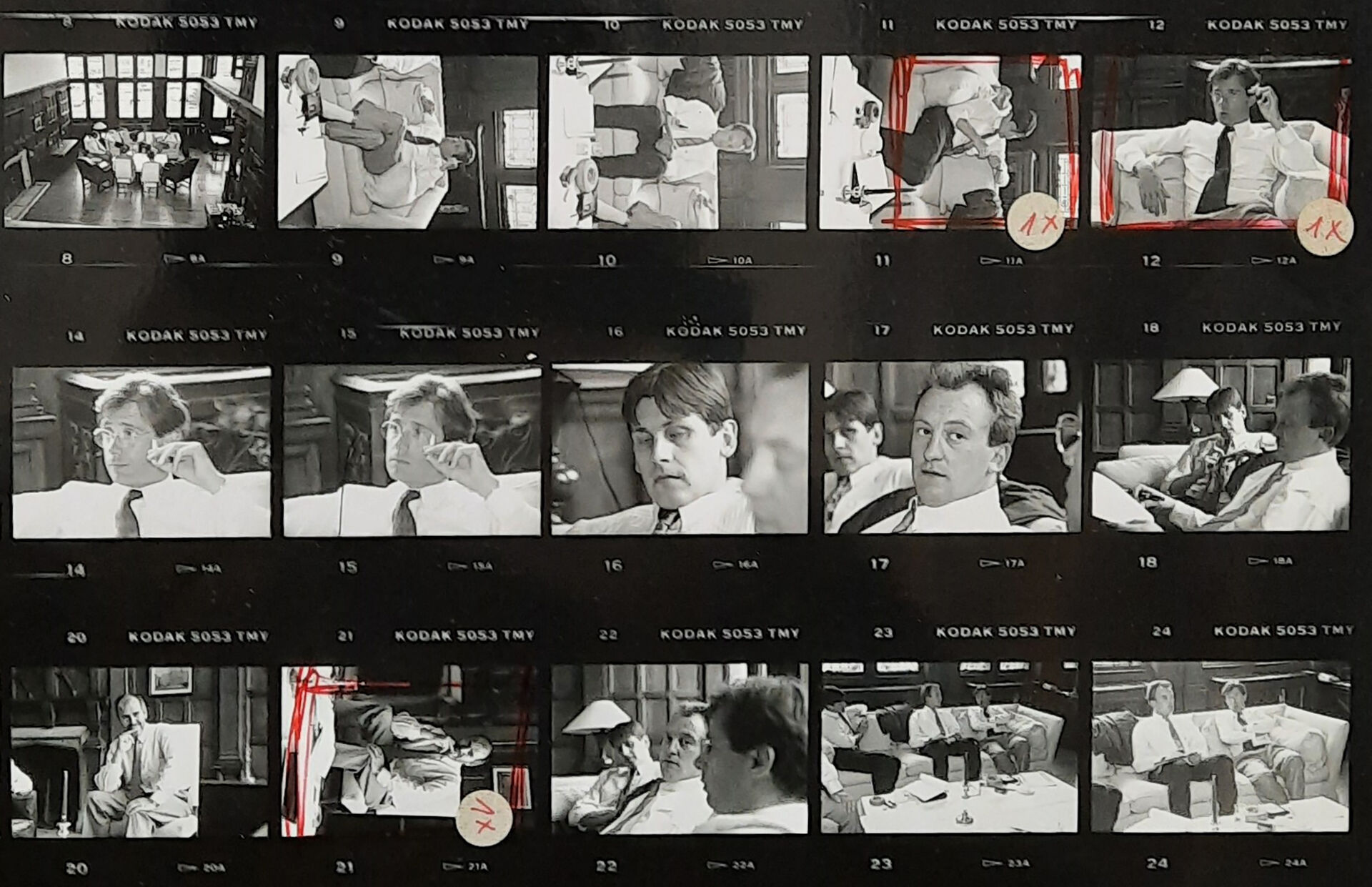

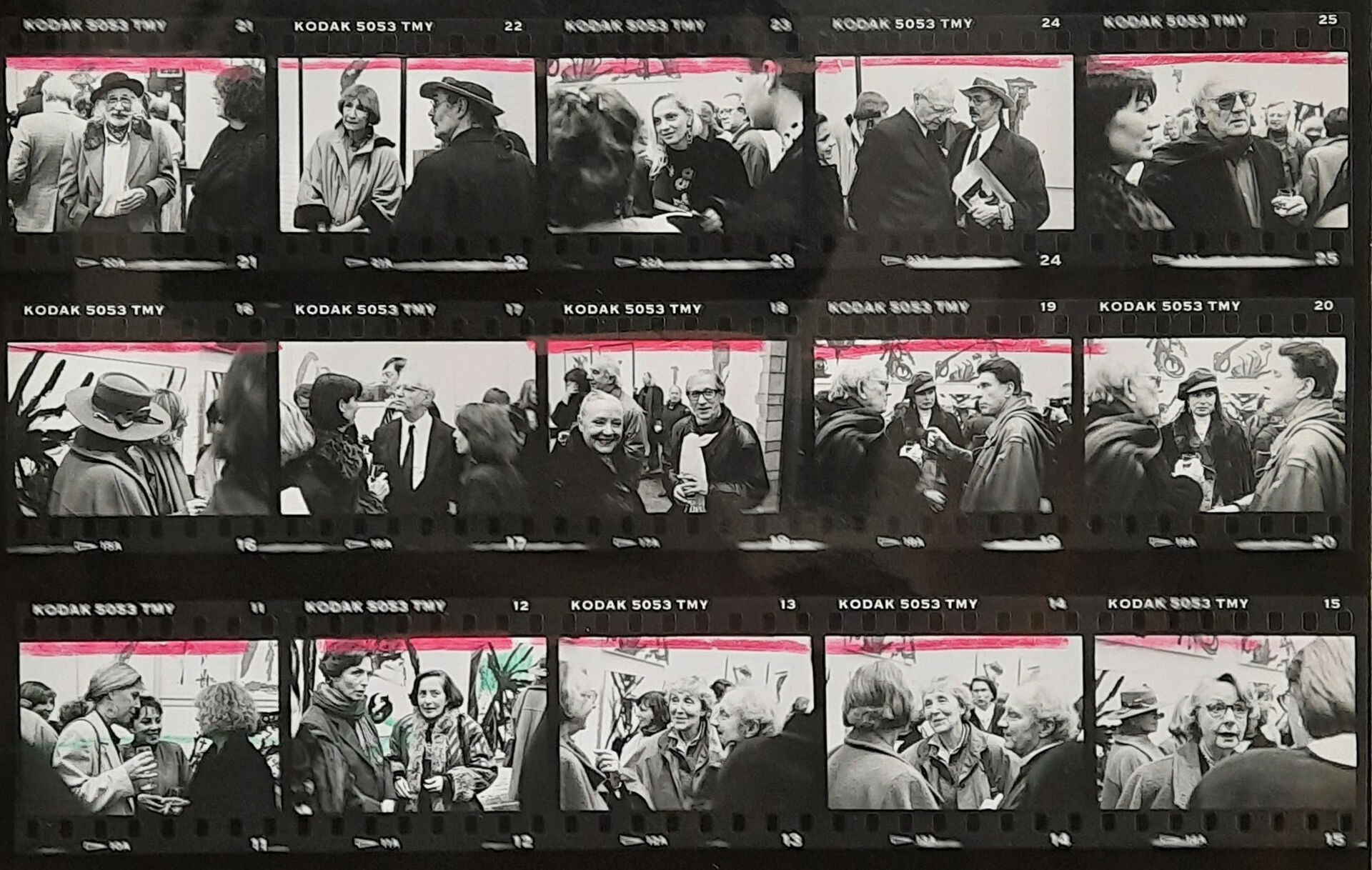

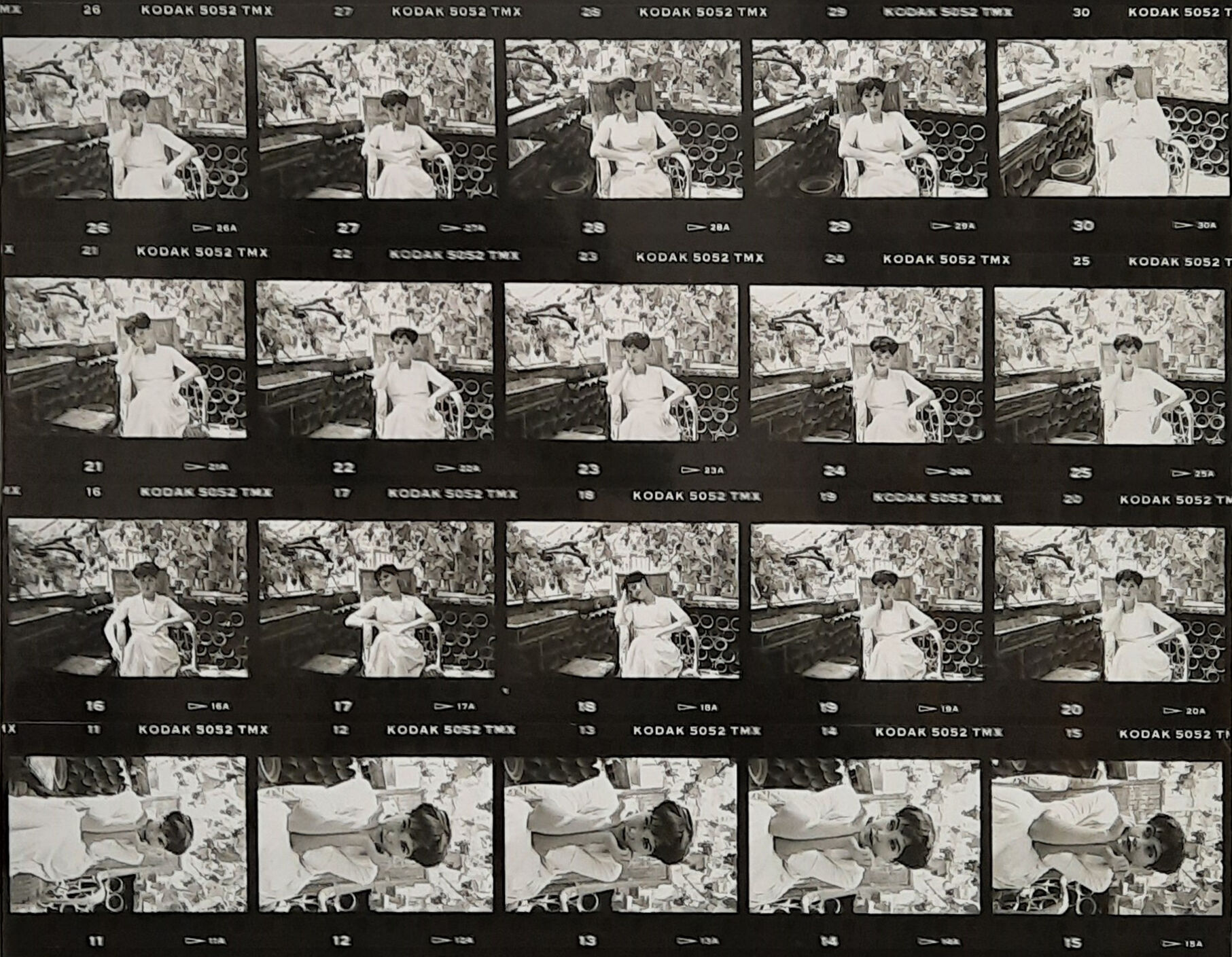

Studio Herman Selleslags, before his archive was transported to FOMU Antwerp, 24 august 2016 © Guy Voet

Legacy Work as a Caring Practice

Legacy work can be understood as a caring practice. Despite the legal and financial implications, it ought to stem primarily from a love and care for the life that went into the work – from the act of pausing and spending time with the treasures and burdens that someone has left behind. While in some instances grief and sorrow may be part of the process, dealing with heritage as a caring practice is less about loss than about nurturing the work, keeping it alive beyond the lifespan of its creator, forging new connections, and preventing an artist’s legacy from slowly falling into oblivion.

Laura Herman

24 feb. 2022 • 10 min

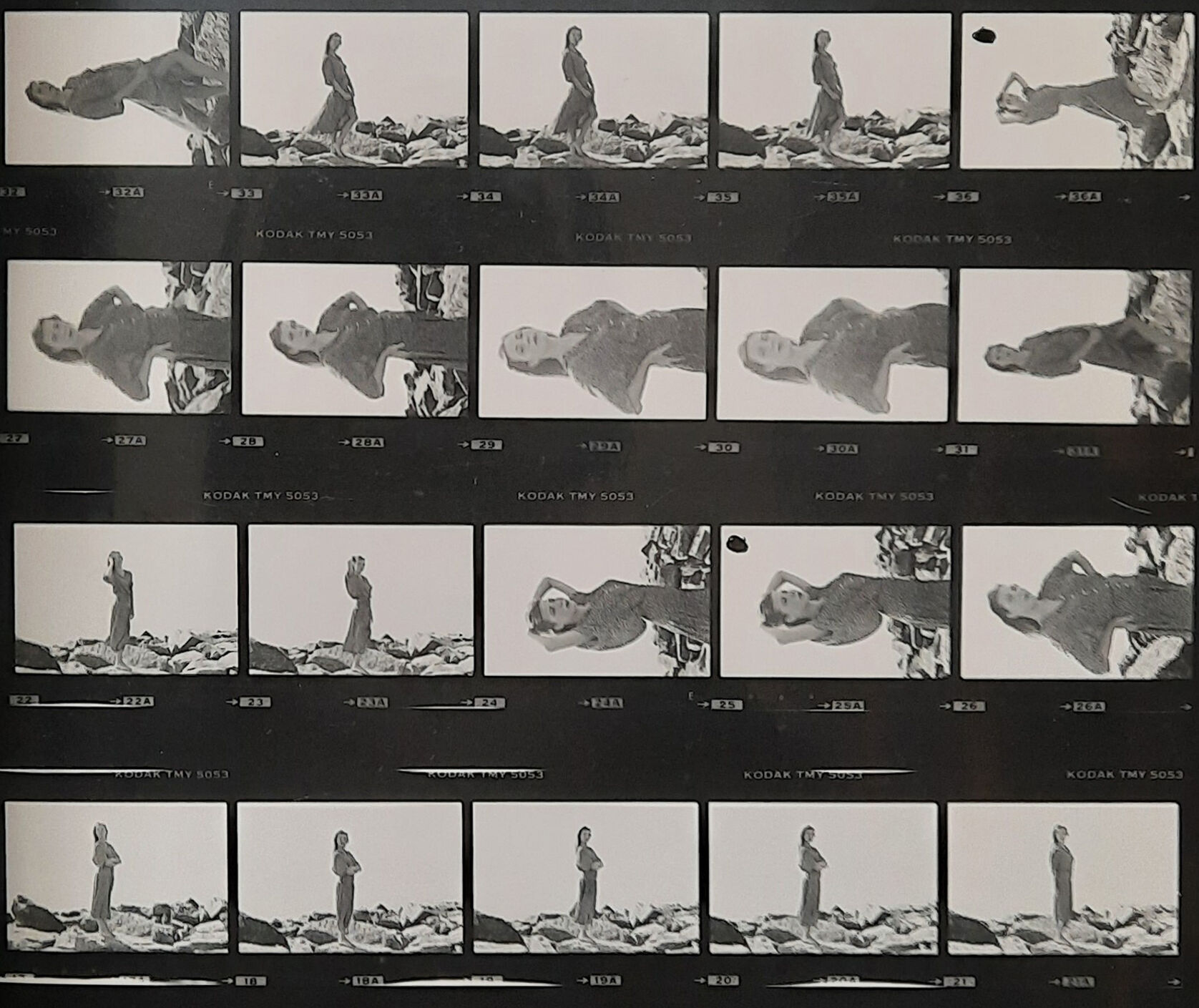

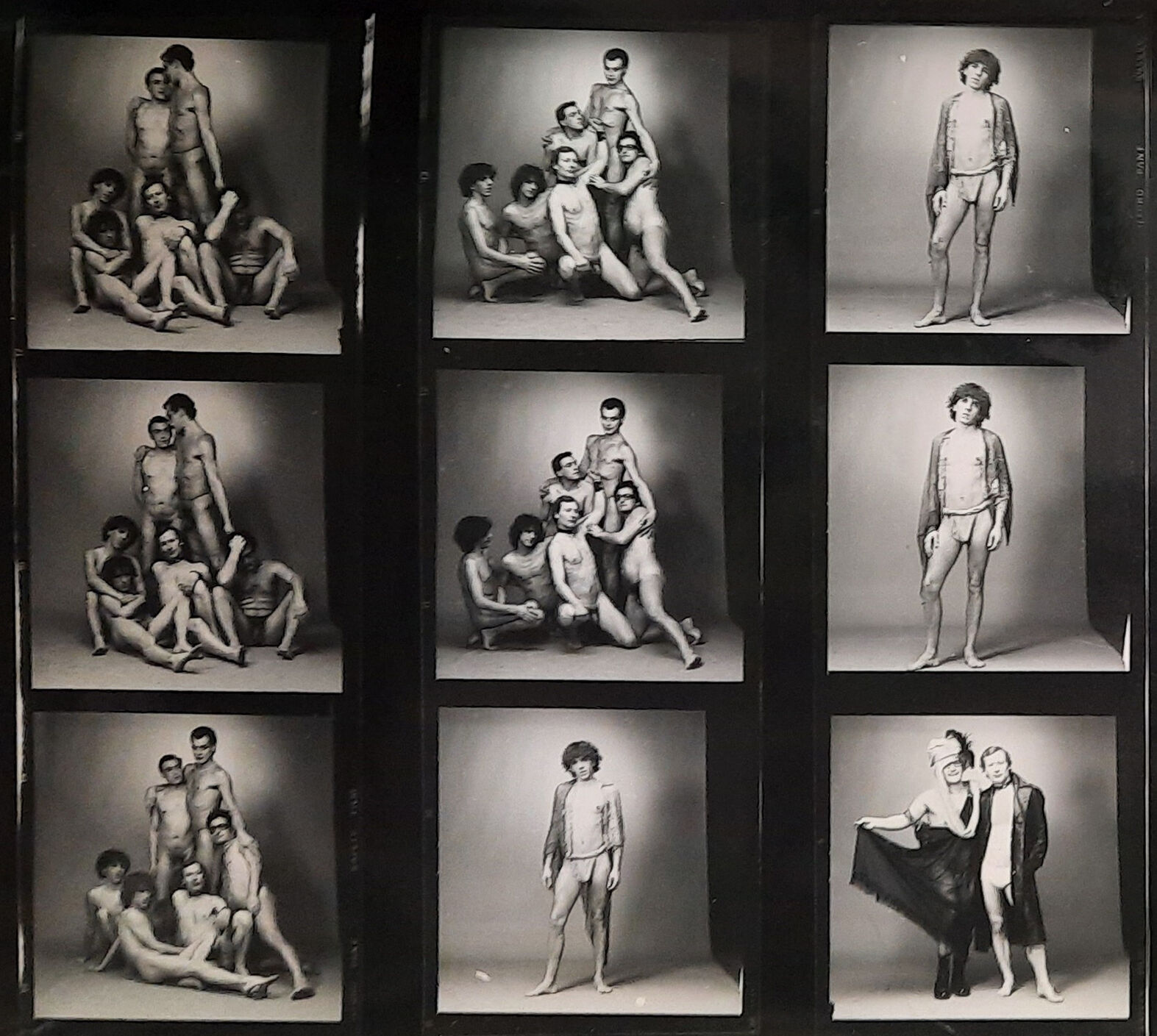

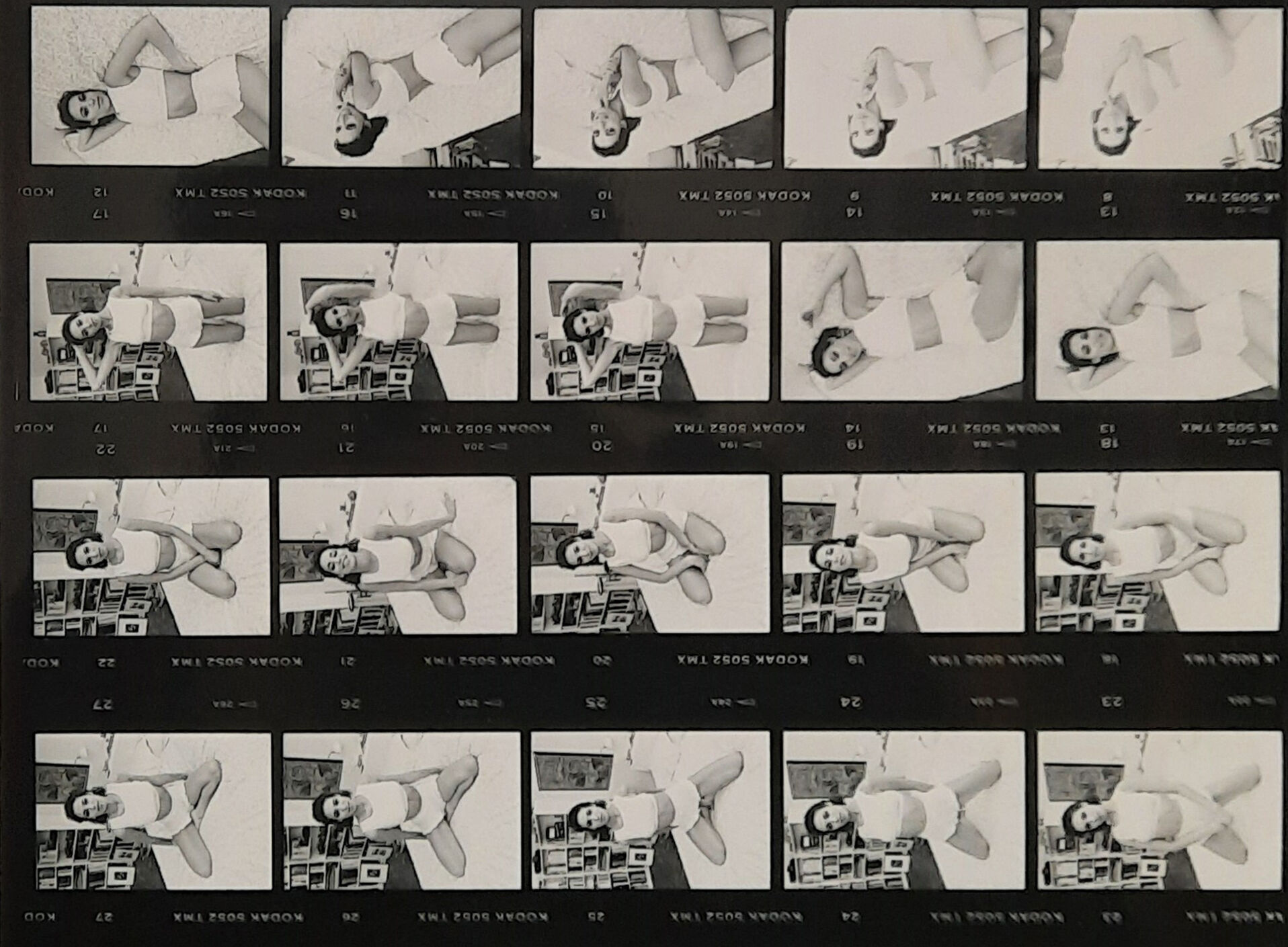

The challenge of posthumous aftercare, however, is the fact that there are no clear-cut rules or specified procedures for dealing with an estate, which makes it a daunting task to decide which strategies or methods will best work with an artistic practice. Photographic practice, in that sense, is even more complex. Photography often gets snowed under compared to other disciplines like literature, film, architecture, and the visual arts. This is because of its complexity – the wealth of materials, which often include large collections of negatives, contact sheets, prints, notes, and related material, as well as the diversity of approaches, which range from architecture, fashion, and advertising to journalism, documentary, and fine art photography. As a result, many photographers’ valuable legacies are in danger of being lost, forgotten, moved abroad, or gathering dust.

The care for artistic work that stays behind when the artist is gone, especially when it comes to applied and fine art photography, is a theme that’s important to Ann Deckers, Inge Henneman, and Aglaia Konrad. Deckers is head of collections at FOMU, the museum of photography in Antwerp; Henneman is a researcher and lecturer in the history of photography at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp who was confronted with the art legacy of her late husband Joris Ghekiere; and Konrad is a photography-based artist who doesn’t know how she should even begin cataloguing ‘the staggering number of photographs she produced across her life’.

In their conversation at FOMU, they discuss the current state of photographers’ collections and archives as potentially valuable resources to society and the arts, and the importance of safeguarding them.A discussion between Aglaia Konrad, Inge Henneman, and Ann Deckers, moderated by Laura Herman, was held at Fotomuseum on 12 August 2021. The conversation was a continuation of a meeting organised by Flanders Arts Institute, in which participants explored ideas related to the establishment a photography-dedicated platform that would unite and strengthen the field of institutional photo organisations and individual photographers. What makes the care for the legacy of photography so different, and in what way does it require different approaches to the ones developed for other art disciplines? Do photographic estates belong to a cultural heritage or to museum collections? How do you separate the important from the unimportant? Where can one find support for the establishment and preservation of photographic legacies, especially for those of photographers who lack the support of a family or large gallery?

Studio Herman Selleslags, before his archive was transported to FOMU Antwerp, 24 august 2016 © Guy Voet

Given the multitude of questions, there’s a strong need to clearly formulate and address the issue of legacy photography. Perhaps the best way to begin is by identifying the various existing initiatives around legacy photography and relying on existing networks. While there are several scattered initiatives in the field that deal with art archives and legacies, Konrad, Henneman, and Deckers point to the need for an autonomous platform that can bundle and refer to the existing expertise of researchers and institutions and give advice and practical guidance specific to the photographic medium. The subject of artists’ legacies is not a niche cultural or political issue.

‘Preserving assets and legacies means safeguarding our cultural heritage,’ says Deckers, ‘We have to face this task now. Not every artist gets their own museum, and not every estate can be transferred to a museum collection. A newly founded platform could offer heirs urgently needed support and assist photographers so that they can systematically organise and catalogue their work during their lifetime. Finally, there is a need to translate the legal information on artistic estates into more comprehensible language.’

The introduction of such a platform could be especially helpful for artists who have no family or gallery, or who have families with very complex interlinkages, and for more hybrid or less-known photographic practices that may otherwise fall by the wayside. No less importantly, as Deckers says, ‘it could help upend the common assumption that digitisation is the answer to storing and preserving photographic practice.’ Besides the fact that digitisation is a very labour-intensive and expensive process, in photography, the unique object is just as important as the reproducible image, and it’s difficult to adequately capture its physical qualities through scanning. Therefore, the preservation of photography needs its own specific treatment.

Reciprocal care

Reciprocity is a dimension of care that can be salient in easing the burden experienced by the heirs of a legacy. Surviving relatives might receive not only a pile of art but also a lot of problems on their plate – uncertainty about how to take over someone else’s work, or worse, entanglement in years of bickering and legal procedures. And, in addition to the emotional investment that naturally accompanies death, Henneman adds, ‘heirs are subject to high moral pressure to guarantee the continued existence of the work in the interests of the artist and the public good, this while often not receiving any public support.’

In addition to highlighting the need for better state support, the risk and uncertainty involved in legacy management also points to the importance of proactive artistic estate planning. How can artists get their affairs in order while they’re still alive and take responsibility for making decisions about their own work and archives? As noted by the Photographers’ Archives and Legacy Project, an exemplary research project devoted to the topic, ‘artists, both established and emerging, ought to need to think through the implications for their work, what future they want for it, what level of public access, and how much supporting and contextual information should be retained and made available.’See, for example, the Photographers’ Archives and Legacy Project at https://www.photolegacyproject.co.uk.

‘There are valuable examples abroad’, Konrad says, ‘from which artists and institutions in Belgium can learn, like the so-called Künstlervorlass in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.’

Künstlervorlass is a precautionary approach to legacy and estate management in which the artist actively plans and takes care of the whereabouts of the work, determining and documenting the form, scope, and nature of any transfer. In consultation and cooperation with experts, the artist can make a will, carefully catalogue the bequeathed material, and determine the most suitable destination for the archive, where it will be preserved and made accessible to the public. Is the photographic work best suited for a library, a historical archive, or an architecture, fashion, or art museum?

What decisions should be made when it comes to the reproduction, distribution, and resale rights of the work? Along those lines, the New York-based Joan Mitchell Foundation has launched Creating a Living Legacy (CALL), an initiative that recognises ‘artists’ voices as essential to the understanding of their practice and legacy’ and issues ‘resources and advice in the areas of career documentation, inventory management, and legacy planning.’Joan Mitchell Foundation, ‘Creating a Living Legacy’, https://www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/creating-a-living-legacy. No doubt these are all crucial aspects of legacy work that are ideally determined by the artist.

While some artists – out of superstition, perhaps, or simply a disinterest in the aftermath of their career – do not plan ahead, such preparation can be regarded as a moral responsibility – a duty to protect others, especially loved ones, from the complicated task of dealing with a disorganised legacy. This proactiveness demands a confrontation with one’s own finitude, and even if it’s not easy, it’s a caring act. At the same time, as Deckers points out, ‘artists ought to be weary of the pitfall of creating a selective story.’ This kind of pre-emptive legacy management should be less about how the artist wants to be remembered and to present their oeuvre than about leaving something organised behind for a multitude of voices to actively work with. This point is aptly put by Heike Roms, a professor in performance studies, in her reflection upon archival care as shared labour: ‘An archive constituted through a continual performance of collaborative practice of care – such may be the legacy of art.’Heike Roms, ‘Archiving Legacies: Who Cares for Performance Remains?,’ in Performing Archives/Archives of Performance, ed. Gundhild Borggreen and Rune Gade (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2012), 49.

Inclusive Care and Supportive Networks

While the discussion between Deckers, Henneman, and Konrad at FOMU started from a necessity and urgency to preserve everything, from prints and negatives to notes and objects, reflections upon the need for an inclusive and widely supported valuation framework also came to the fore. The question of who’s afforded care, and by whom, is a crucial one. As noted by the newly established collaborative research network LAsting Legacies: Contemporary Artists’ Estates Between PUblic Heritage and Private INheritAncE (Lacunae) at the University of Maastricht, we should ‘take stock of the current connections and disconnections in networks of care around contemporary artists’ estates and how they serve to include and exclude certain artistic practices and marginalised groups.’Networks of Care: Preserving Artists’ Legacies through Collaborative Archival Practices, discussion panel at Maastricht University, 10 June 2021, https://www.maastrichtuniversi....

What stands out in Belgium is that large estates are often run by women tending to the work of a deceased husband or father, reproducing the dynamic of unevenly distributed caring responsibilities between women and men and between the family and the state. Inclusive and reparative legacy work and archival care thus implies that institutions should acknowledge the marginalisation or absence of certain voices and build collections and archives that represent global human diversity and histories. Besides the question of representation, archives and collections only become valuable and alive when they’re usable, and when they become subject to a plurality of perspectives. Ultimately, photographs are especially valuable resources as both inheritance pieces and testimony for doing memory work.

Equally important in that regard is the need to look beyond standardised preservation practices to develop more sustainable models of caring for legacies that rely not only on conservation but also on embodied knowledge or immaterial cultural artifacts. Legacies could then be at the heart of an active practice of publishing, performance, and presentation, open to a multitude of perspectives.

Following the growing concern with decolonising archives and collections, we can also question the permanence of art objects and documents altogether. The ideology of conservation is increasingly being countered by art historians like Clémentine Deliss in favour of an understanding of art as transference and a point of contact for sensory engagement. There’s a need to challenge the modernist idea that the highest achievement for an artist is to create work that lives on for eternity, or at least for the minimum bar of a thousand years.

Lastly, there are delusions we should be wary of when thinking through care. According to Emma Dowling, who writes on the problems and possibilities of care in our current time joint, there are ‘two sides to this self-care fix that together articulate an outlook on the world that is congruent with the logic of financialised capitalism.’ She writes, ‘First of all: take care of you, because you are your own most valuable asset – a form of human capital that will yield high economic returns if you look after it. Second: take care of you, because nobody else will. Public services continue to be squeezed, collective solidarity undermined, and labour markets deregulated.’Emma Dowling, The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How Can We End It? (Verso Books, 2021), 167.

A proposed antidote by Dowling is collective or collaborative care: ‘Self-care can also involve setting up supportive networks that are not separate from the endeavour of making sense of the social structures and unequal power relations that we exist within.’Ibid., 187. This kind of supportive network and collaborative care comes up when Henneman looks back on the period shortly after her husband, Joris Ghekiere, passed away, and Hélène Vandenberghe, daughter of Philippe Vandenberg, and Stella Lohaus, daughter of Bernd Lohaus, among others, ‘came to her rescue’, giving her the heartfelt advice she needed. Vandeberghe and Lohaus cofounded SOS Artistieke Nalatenschap with the aim of providing practical advice on dealing artistic legacies within Belgium, and it’s an example of how supportive networks can counterbalance the individualism of the artist’s estate through knowledge sharing. It’s precisely this kind of fledgling collaborative effort and ongoing engagement by peers going through similar experiences that can offer the incentive for the platform Deckers, Henneman, and Konrad are hoping for – an initiative that not only offers advice on the management of photographic legacies and estates but also critically engages with the challenges and assumptions surrounding the discipline and its treatment.