Keeping Pieces of Home: The Exiled Identity in Three Works

‘L’étranger te permet d’être toi-même, en faisant, de toi, un étranger.’ (Edmond Jabès)

In 1957, Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet (1902–1963) wrote these ringing words: ‘exile is a hard job’.'Şu gurbetlik zor zanaat zor…’ written in May 1957 in Varna as part of a series of poems Hikmet wrote while in exile in Bulgaria. Quoted in Nâzım Hikmet, Yeni Şiirler (1951-1959) (Istanbul: Adam Yayınları, 1987), p. 116. The phrase became the soundtrack of many migrant Turkish families in Europe. With a similar recognition, artist Nil Yalter (b. 1938) used this sentence as the title of several public artworks and her first major retrospective in 2019.The first major retrospective of her œuvre took place in Museum Ludwig, Köln (9 March–2 June 2019). Throughout her oeuvre, Yalter has shown how exile and migration deeply affect personal lives. In comparable ways, artists Zineb Sedira (b. 1963) and Yto Barrada (b. 1971) have compellingly focused on the identities and relationships formed by exile. This article undertakes a journey of three photographic works by Yalter, Sedira and Barrada.

Zeynep Kubat

05 feb. 2021 • 13 min

Seeing double

Any medium that adopts documentary techniques to capture reality may be questioned regarding the truthfulness of its representations. At what point does a fictional narrative or the subjectivity of the creator infiltrate an objective truth?Hito Steyerl, ‘Documentary Uncertainty’, A Prior Magazine 15, June, 2007, http://www.aprior.org/apm15_st...; Trinh T. Minh-ha, Documentary Is/Not a Name (1990), quoted in ed. Julian Stallabrass, Documentary, Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art, (Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press & Whitechapel Gallery, 2013), 68; Philip Rosen, Change Mummified: Cinema, Historicity, Theory (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 240. The greater the attempt to objectify representation, the greater the risk of making mistakes. As such, documentary art can correctly approach truthful realities by getting rid of all pretences of objectivity.I won’t distinguish between documentary makers and visual artists, since the genre of documentary has seeped into many forms of visual culture. As Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg stated: ‘Documentary didn’t need artists to teach it creativity and reflexivity, yet its predominance in contemporary art is undeniable and demands examination’ (Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, ‘Introduction: The Documentary Attitude’, in Documentary Across Disciplines, eds. Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg [Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016], 18. Realities are always laced with memories, doubts, multiplicities and the affectations of individuals. ‘Has photography quietly replaced your memories with its own?’Geoffrey Batchen asked in his text on memory and photography.Geoffrey Batchen, Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), 15. Even though Batchen was talking about the experience of watching your own family memories in photographic documents, looking at images of other migrant families creates a similar experience for me. When I see the photographs of Yalter, Sedira and Barrada, I recognise them as my own. Because we share the traces of exile, their ambiguities assert mine. How did they succeed in picturing a collective affect, a collective truth, while surpassing boundaries of language, culture, time and space?

Migration is always a form of exile, even in the case of voluntary mobility, since it entails the experience of dislocation. The exiled identity is generational and has an afterlife in the identity of the descendants of first-generation migrants. They are marked by confusion: there is a ‘double consciousness’ (W.E.B. DuBois), a ‘double perspective’ (Edward Said) or a ‘double frame’ (Homi Bhabha) in which their (hi)stories are constructed.Demos, The Migrant Image (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 3. Ethnic and national identities become complementary and two (or more) different languages, psychologies and cultural forms of knowing and experiencing create doubtful, mixed-up identities. The sense of rootedness and belonging is disrupted by the expectations of the country that has been left, the diasporic community in a new country and governmental demands of integration and assimilation. To what culture do I belong? Who should I become? Such questions about identity are difficult to represent because they implicate many converging and sometimes contradictory truths.

Yalter, Sedira and Barrada have succeeded in representing these double frames by using personal narratives and experiences as documents and by embracing the speculative nature of reality in itself. What connects all three artists is their search for common ground within the exiled identity – something that comes close to the so-called truth of migrant life – and their purposeful use of ego-documents (narratives, interviews, photographs, notebooks, memories, socio-economic experiences and their own family relationships) as the gateway to a truthful representation of migrant realities.

My story is your story

As Roland Barthes so endearingly proved in his essayistic book Camera Lucida (1981), photography is an uncertain medium.Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 16-18. Not only does the delicate balance between the representing gaze and represented subject create ambiguous object-subject relationships, the complexity of ‘that-has-been’Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 76-77. in time and space is at all times embedded in a photograph. It is where a past existence meets a present reality of interpretation and emotion. Yalter, Sedira and Barrada have used this ambiguous constitution of photography in transformative ways that could create, to use the words of T.J. Demos, ‘new modelings of affect.’T.J. Demos, The Migrant Image. The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), xiv. In her photographic series Turkish Immigrants (1977; Figure 1), Yalter used ethnocriticalThis is a term the artist uses to describe her artistic research and to distance herself from ‘sociological’ or ‘ethnographic’ research. Her methodology surpasses traditional research forms and entails a deeply grounded criticism of the socio-economic situation of migrants throughout Europe, often also adding a feminist critique to the role of female family members in their exiled contexts. research to document migrant families in different contexts. In her photo installation Mother, Daughter and I (2003; Figure 2), Sedira harnessed the full potential of (self-)portrait photography to recreate the intricate relationships between migrant mothers and daughters. In her series of document photographs, The Telephone Books (or the Recipe Books) (2010; Figure 3), Barrada delved through the notebooks of her own family to create her works. All three projects carry the shared ambiguity of traveling, living ‘elsewhere’ and the fragile construction of in-between identities, and all three artists departed from their own biographies to construct an image.

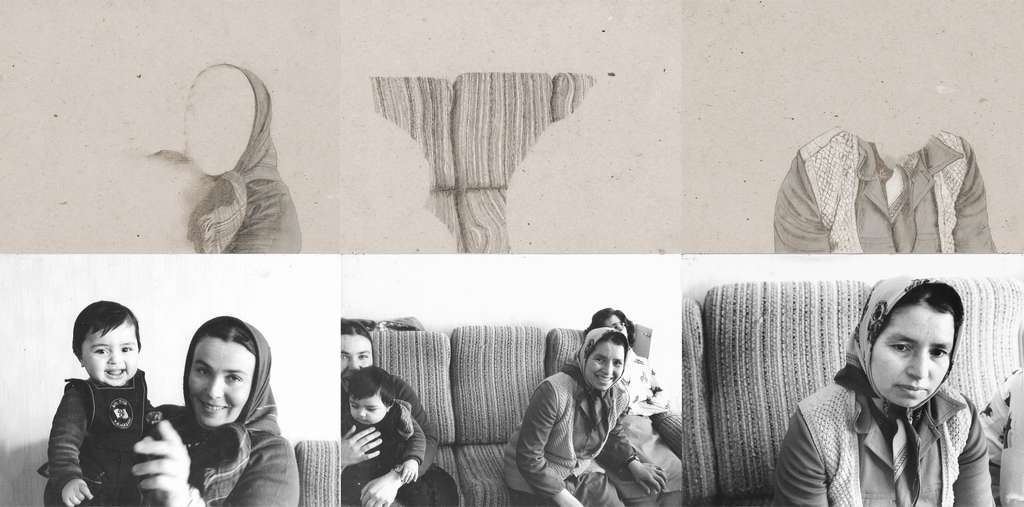

After she moved from Istanbul to Paris in 1965, Yalter explored and documented the socio-economic position of economic migrants from Turkey from an activist and feminist standpoint by visiting them in domestic contexts. This ethnocritical research became the basis for her photographic drawing series Turkish Immigrants. The images can be read as a subjective mapping of people, objects, clothing, atmosphere, furniture and emotions that may help us grasp their lived realities. In the chosen detail of the installation, we see three photographs of women sitting in a couch at home. Every picture shows another angle in their position. Each new position represents another relationship: a mother and child, a young female family member, and a slightly older female figure who has a central position in two photographs. Is she the materfamilias when the men are out? Perhaps she is the mother-in-law of the young mother with child, since Turkish tradition dictates that the bride leave her own family and move into her husband’s family home.

Figure 1:

Nil Yalter, Turkish Immigrants, 1977 (detail from the collage series).

Photo and pencil on paper © Nil Yalter.

Yalter’s independent life in Paris was quite different from that of these women, but she stayed aware of the sense of double imprisonment they could experience.Sabine Oelze, ‘Nil Yalter: Turkish-French art pioneer emerges from exile’, Deutsche Welle (March 6th, 2019). https://www.dw.com/en/nil-yalter-turkish-french-art-pioneer-emerges-from-exile/a-47789681. While their husbands worked in factories and mines, most women had to stay home (first imprisonment), disconnected from their new cultural and linguistic environments (second imprisonment), in order to fulfil their traditional care-taking tasks. Might the delicate drawings of Yalter, in which she erases faces and bodies to only keep contours of clothing and furniture, symbolise the loss of identity she discovered within these first-generation economic migrants? The woman in the middle picture is laughing joyously in her here and now. In the picture on the right, her big smile is replaced by an expression of sorrowful recounting. How fast things can change, just like the continuous motion of one’s identity.

In her photographic triptychs, Sedira tackles the same problems of identity but from a more positive stance. ‘How do you tell your identity when your identity is quite complex, perhaps painful at times, but also very rich?’Guggenheim Museum, ‘Artist Profile: Zineb Sedira on Family, the Sea, and her videos’, YouTube, June 8, 2017, video, 5:36. The artist made several (self-)portraits with her mother and daughter in which she positioned herself as an interpreter between them, a mediator between two different manifestations of the exiled identity within one family line. It reminds us of the fact that many sons and daughters acted (or still act) as interpreters for their parents in a new ‘home’ country. Some parents were illiterate; some simply couldn’t learn the language due to discriminatory policies and demanding labour hours. Sedira used her own affective biography as a method to share the pain and richness of a multicultural identity.

Figure 2:

Zineb Sedira, Mother, Daughter and I, 2003 © Zineb Sedira.

All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020.

Image courtesy Kamel Mennour, Paris.

The portraits each received an oval extension piece that focuses on the holding of hands as a red thread throughout the relationship and the flawed communication between the three women. This is not a group portrait: like in a sacra conversazione, we see the women exchanging thoughts and memories one by one, in an intimate atmosphere, before the viewer. The grandmother looks with pride and joy to her granddaughter, almost with relief (all’s well that ends well), but she seems to reserve a deeper gaze for her daughter. Perhaps now that Sedira is a mother too, she may fully understand her own mother’s experiences with the hardship of exile, the difficult passing on of heritage in another country and fighting or accepting expectations of motherhood in different cultures. In ancient Greek, the word ‘storgè’ expressed familial love and unbreakable family bonds as strong and sturdy as the sound of the word itself. I recognise the way Sedira, her mother and her daughter hold each other’s hands in solidarity and exchange experiences of motherhood and childhood. It’s as if these hands are the tools in a ritual to pass over the subjective experiences of all their former mothers to each next generation, to let the storgè flow and store it in these photographic portraits.

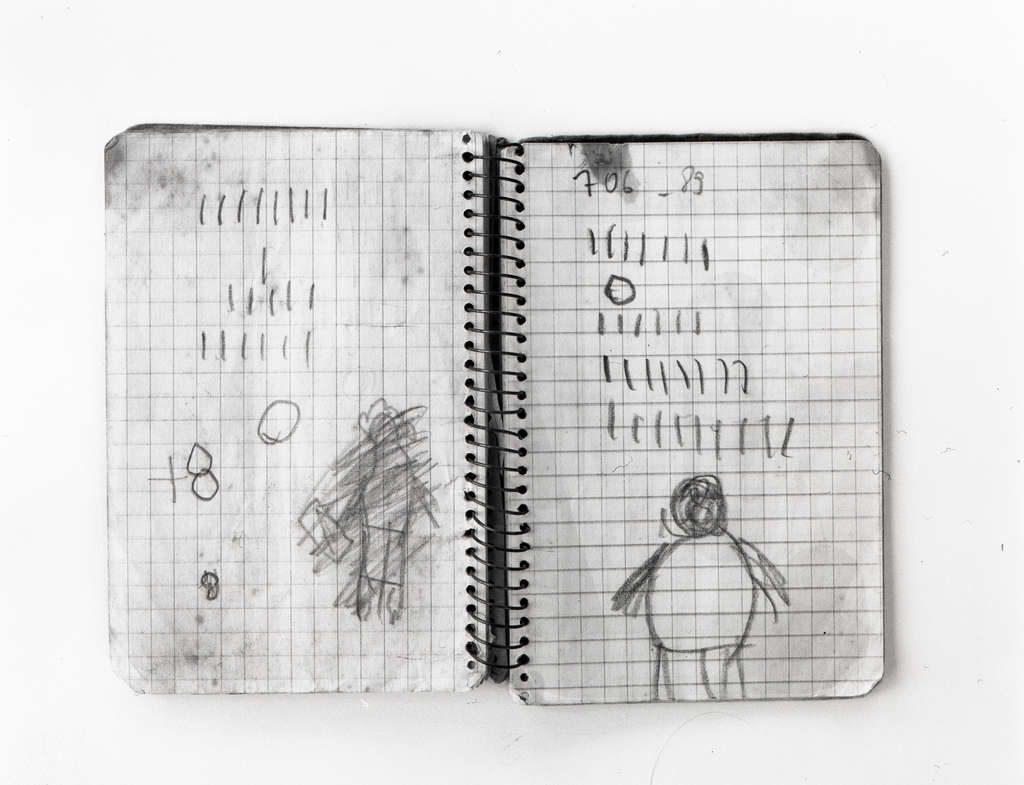

Figure 3:

Yto Barrada, The Telephone Books (or the Recipe Books), nr. 5, 2010, C-Print.

Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

Photographed by Capital D.

In the same way Yalter and Sedira explored the construction of complex cultural identities through intergenerational communication and language barriers, Barrada unveiled the consequences of illiteracy in her own family. Barrada’s illiterate grandmother, named Z.A.B., had ten children. The travels and migrations of her children necessitated her keeping in touch with them via telephone. She devised a coded drawing system to remember phone numbers and associate each child with their corresponding number. Next to noting coded lines and symbols to substitute numbers, she made simplistic drawings of her children, each time adding an identifying trait: the one with the glasses, the one with the four children, and so on. Barrada photographed the pages in this notebook, doubling the documentary value of the document itself but also showing their artistic value as simplistic coded portraits of real people. On the fifth photographic print of this notebook, we see a double page. On the left, there is a drawing of a person holding something that’s been coloured over. Is it a book, a contract, a letter or a small suitcase? Is this a child of hers who passed away and is no longer available by telephone, or did she simply draw a mistake? On the righthand page, there is the drawing of someone with no clear personal traits other than a nicely rounded belly. The graphite smudges on the chequered pages give away the intensive use of this notebook. The Z.A.B.’s coded and idiosyncratic writing system reveals no specific signs of affection for the represented children. It’s not a diary, but it does carry her memories and associations about each of her children in its most minimal appearance. The documentary character of Barrada’s work is to be taken quite literally: it’s a photographic documentation of a document; it’s data documenting ten children. However, the notebook itself reveals important information about the experience of identity in a dispersed family, without using any words, realist portraits, names or other ‘true’ data. It gains realism in speculation by its candid nature and honesty.

The different examples Yalter, Sedira and Barrada provide do not serve as objective documentations of the proposed complex exiled identities. They remain hypothetical, searching and transformative in the sense that they’re wandering through individual memories and experiences to achieve knowledge about commonalities, so the artists can also give themselves a clearer place within the world. Yalter, Sedira and Barrada approach ego-documents with aesthetic freedom. As George Didi-Huberman stated: ‘it is in the very point where evidence is doubtful that artistic practice frequently turns up to offer its own answers. Hypothetical, fragile or paradoxical answers, of course.’Georges Didi-Huberman, ‘Emotion does not say “I”: Ten Fragments on Aesthetic Freedom’, in Alfredo Jaar: La politique des images, ed. Nicole Schweizer, (Zurich: JRP Editions, 2007), p. 57-70.

De bouche à l’oreille: Sharing feeling

The lonesome artist or researcher can never truthfully represent complex identities. No woman is an island, and neither are Yalter, Sedira and Barrada. One of their most important documentary techniques is the creation of dialogue between themselves and others. Yalter relies on personal encounters and testimonies. She closely collaborated with sociocultural workers, sociologists, political partners and artistic partners. In contrast to Yalter, who mediates the lives of others, Sedira and Barrada expose their own lives by targeting their own experiences through documentation. Barrada uses an ego-document from her family as a ready-made for a photographic series, whereas Sedira creates her own ego-documents by portraying herself with her mother and daughter in full candour.

Yalter, Sedira and Barrada revealed generational (hi)stories, complex identity struggles in the emotions they captured and points of recognition for everyone who shares an exiled identity to any degree. Their work consists of what Sophie Berrebi would call ‘dialectical documents’: they’re ambiguous confirmations of the existence of what is represented, but at the same time, they also reference the existence of something localised beyond the image itself.Sophie Berrebi, ‘Documentary and the dialectical document in contemporary art’, in Right About Now: Art & Theory Since the 1990s, eds. Margriet Schavemakers and Mischa Rakier (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2007), 201. As Yalter showed in her photocollage, one cannot simply depict identity. She had to use her drawings to convey a sense of loss. Sedira had to add a visual referent to her portraits that focused on the holding of hands, symbols of relation and exchange. Barrada’s photographic reproduction of the telephone books is referential to the lives of her grandmother and her ten children. Dialectical documents are characterised by ambivalence, by the possibility of placing different times and spaces on one storyline, by the possibility of opening the image and revealing different levels of relationships between reality and representation.

By using personal narratives and experiences as documents, and by embracing the speculative nature of reality itself, artists can find new ways of depicting converging truths. Yalter, Sedira and Barrada disclosed the ambiguity of the represented identity itself and the uncertainties embedded in uses of personal narratives. They conducted intense research into personal documents and photographic and other archives of their own and/or other individuals. They bravely dove into the messy reality of personal lives in order to search for commonalities. By these means, they succeeded in unravelling some delicate truths of exiled identities in their carefully constructed photographic installations.