I won’t pretend that I’ve fully grasped the ideas in Barad’s monumental book, or that this short summary captures their complexity, but they’ve helped me to articulate my frustration with the line that’s often drawn between discourse on photographic technology (the various instruments and processes that we currently use to create and share images) and discussions of photography as a social practice.

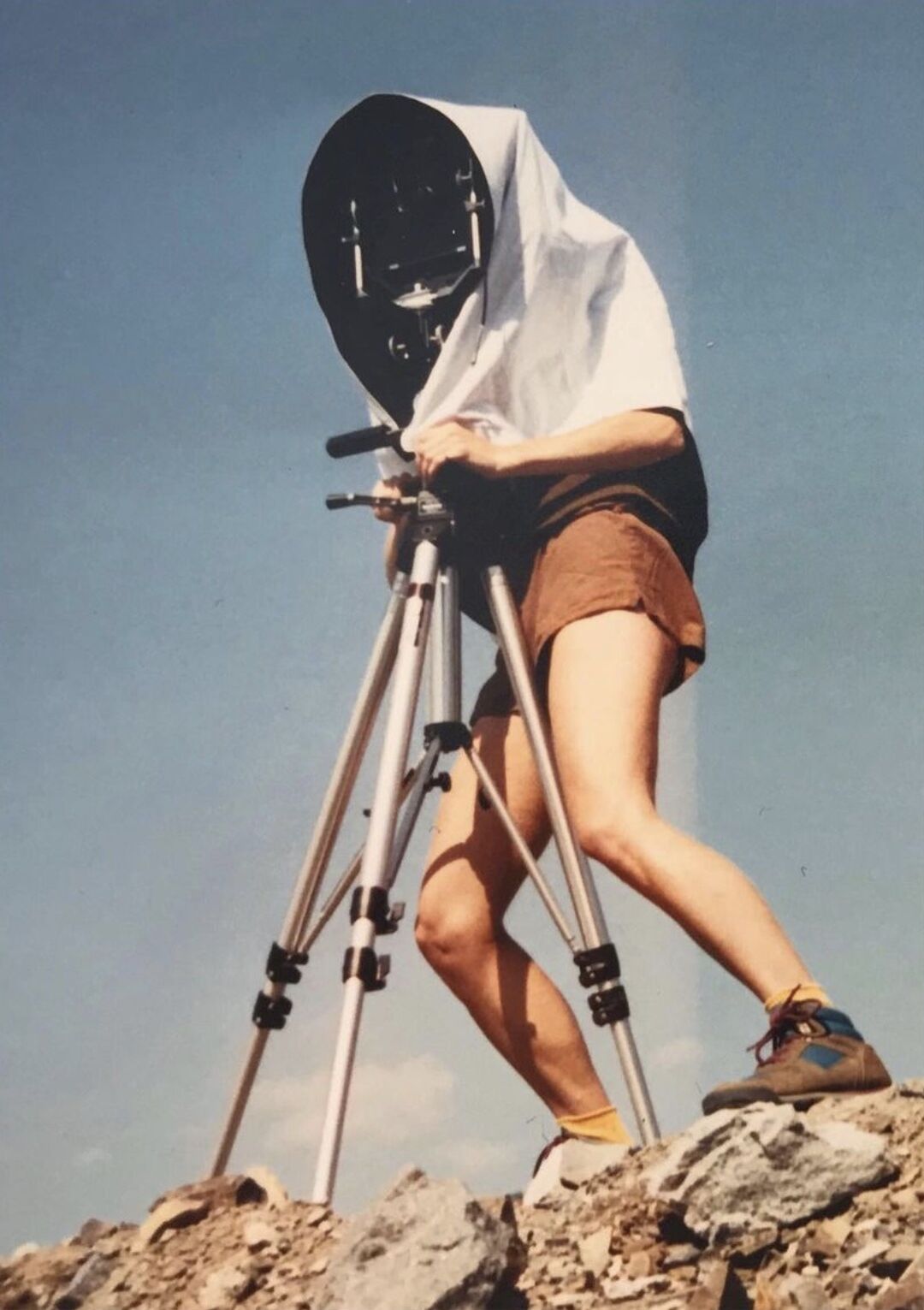

Eugenie merges with her Cambo SC whilst photographing at the Poudrette Quarry in Sainte-Hilaire, Québec

The current trend for ‘visual storytelling’, for instance, treats the camera as a neutral tool that’s ontologically separate from the people and circumstances it’s used to represent. Surely cameras and persons are distinct things? Not according to Barad, who makes some paradigm-shifting claims about the relationship between discursive practices and material phenomena. Technologies, she writes, aren’t distinct entities with fixed exterior boundaries – nor, for that matter, are human subjects – and representations aren’t created by human agents using technologies to communicate their ideas. Instead, meaning emerges performatively, the outcome of practices involving diverse human and non-human agencies. Camera; photographer; subject; social, political, and historical contexts – all of these are implicated in a material–discursive photographic ‘apparatus’ that is unique to every photographic encounter. None of these components, she argues, have discrete identities before the encounter takes place: instead, meanings, properties, boundaries – and, significantly, exclusions – are all enacted within, and products of, the encounter itself. In other words, the line between photography as advocacy and photography as techne – or, for that matter, any of the divisions that characterise photographic discourse – is neither inherent nor immovable. As someone who worries occasionally that my fascination with photographic technology could be seen as a way of sidestepping politics, this is transformative.

Note to the reader. This article is part of Trigger’s 2023 ‘Summer Read’ series. We invited writers, researchers, photographers and curators to share what is currently occupying their mind through one publication they have been (re)reading during summer. What matters to them is now being recast as a challenge for today. Highly personal entries to a diversity of publications (photobooks, studies, monography, essay, historical research) lead us – readers of these readers – to reorient our gaze on (the history of) images and photography.