Imperial Impact

This article first appeared on Still Searching, where Ariella Azoulay published a series of essays called Unlearning Decisive Moments of Photography. In this series, Azoulay sought to invert common assumptions about the moment of the emergence of photography that present it as a sui generis practice and locate said moment in the mid-nineteenth century and in relation to technological developments and male inventors. Instead, she proposes to locate the origins of photography in the ‘New World’, to use the early phrasing of European colonial enterprise, and to study photographs alongside early accounts of imperial expeditions. The essays are based on her forthcoming book Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, which is out through Verso in fall 2019.

Ariella Azoulay

15 nov. 2019 • 7 min

Two concepts play a fundamental role in this new work and thus in the essay below; these are ‘unlearning’ and ‘imperial rights’. In order to acknowledge that photography’s origins are in 1492, Azoulay posits that we have to unlearn the expertise and knowledge that call upon us to account for photography as having its own origins, histories, practices or futures. She wants to re-write that history: photography does not represent a domain apart, and you cannot hence simply situate it in the early nineteenth century. Her critical – ‘unlearning’ – approach makes us want to explore photography as part of the imperial world in which we, as scholars, photographers, or curators, operate. According to her, photography, like other technologies, is rooted in imperial formations of power and the legitimisation of violence in the form of rights exercised over others.Among these rights Azoulay specifies ‘the right to destroy existing worlds, the right to manufacture a new world in their place, the rights over others whose worlds are destroyed together with the rights they enjoyed in their communities and the right to declare what is new and consequently what is obsolete.’

The second point she makes is, that when photography really emerged, it didn't halt this process of plunder that made others and their worlds available to the few.The ‘few’ can stand for the explorers of new worlds, the settlers, colonial metropoles, officials and representatives of imperial powers, and in some cases even, as becomes clear in this essay, the so-called ‘concerned photographers’. It rather accelerated and provided further opportunities and modalities for pursuing it. The right to take a photograph of objects, art, wealth etc., ‘we’ brought back from new discovered territories, is based on ‘the right to appropriate others’ wealth, resources, and labor’.As such, explorers like Amerigo Vespucci for instance, proclaimed and enacted certain ‘imperial rights’ in early letters written at the turn of the fifteenth century. These new rights, the exercise of which involved mass destruction, were manufactured under the pretext of the promotion of knowledge involved in the discovery of ‘new worlds’. Rather than conceiving of photography as a means to document discrete cases of destruction, we need to ask ourselves how photography participated in this destruction and ultimately examine if and how it can play a part in imagining ways out of it.Azoulay’s critical assumption, stated in the original essay, is ‘that the ubiquity of destruction both precedes and enables the ubiquity of photographs. The latter is derivative of the former and should be read in connection with it.’ All this implies that photography didn’t so much initiate a new world as it was built upon and benefitted from imperial looting, divisions and rights that were operative in the colonisation of the world to which photography was assigned the role of documenting, recording or contemplating what was already there.

Even as photography becomes more and more specialised, with its own division of ‘experts’, it tends to ‘structurally’ deny its impact when taking for granted these imperial rights. That’s Azoulay overall strategy: to lay bare ‘the set of imperial rights that continue to lie at the basis of our political regimes’. The unlearning she proposes re-envisions the impact photography in a non-imperial way: taking photos differently means really including the other(s).See her fourth blog/essay for this. In order to do that, ‘one has to [first] engage with the imperial world from a non-imperial perspective and be committed to the idea of revoking rather than ignoring or denying imperial rights manufactured and distributed as part of the destruction of diverse worlds’.

'Concerned Photographers', selection of book covers

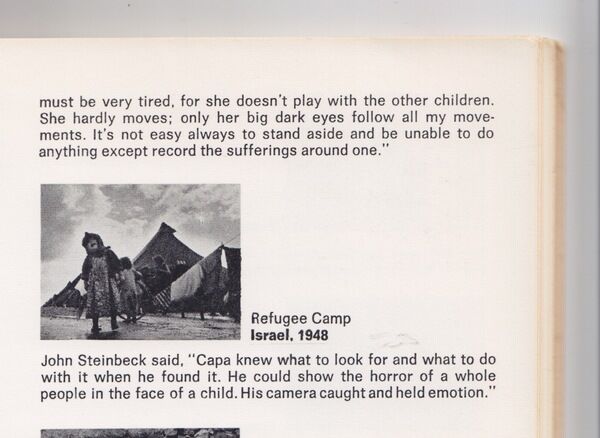

Burt Glinn, photos taken in 1956 of Palestinians persecuted by the State of Israel.

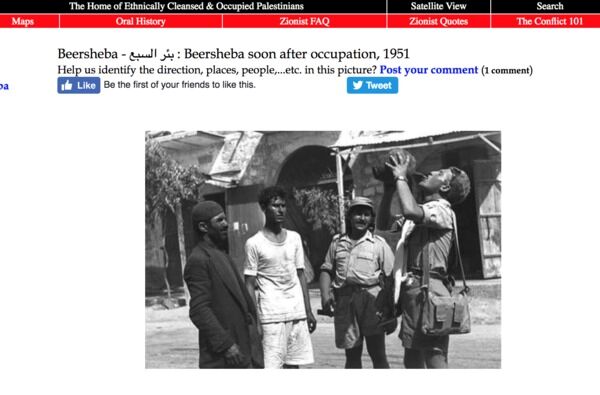

Palestine Remembered, http://www.palestineremembered.com/OldNewPictures.html

Through [a] combined activity of destroying and manufacturing ‘new’In the introduction of her first essay, Azoulay defines this moment of the ‘new’: ‘The attachment of the meaning “new” to whatever imperialism imposes is constitutive of imperial violence: it turns opposition to its actions, inventions, and the distribution of rights into a conservative, primitive, or hopeless “race against time”—i.e., progress—rather than as a race against imperialism. The murder of five thousand Egyptians who struggled against Napoleon’s invasion of their sacred places and the looting of old treasures, which were to be “salvaged” and displayed in Napoleon’s new museum in Paris, is just one example of this. In the imperial histories of new technologies of visualization, both the resistance and the murder of these people are nonexistent, while the depictions of Egypt’s looted treasures, which were rendered in almost photographic detail, establish a benchmark, indicating what photography came to improve.’ worlds, people were deprived of an active life and their different activities reduced and mobilised to fit larger schemes of production and world-engineering. Through these schemes, different groups of governed peoples were crafted and assigned access to certain occupations, mainly non-skilled labour, that in turn enabled the creation of a distinct strata of professions with the vocational purpose of architecting ‘new’ worlds and furnishing them with new technologies. Such professions housed experts in distinct domains—economics, law, politics, culture, art, health, scholarship and so on—that were differentiated and kept separate in racialised worlds engendered by imperialism. Experts in each domain enjoy ‘the right to shape societies’ according to their vision or will, to study them and craft visionary templates in order to provide solutions to problems generated by other experts.

Photography was shaped into such a model, with its own strata of experts. This class of expert professionals denied their implication in the constitution and perpetuation of the imperial regime and quickly convinced themselves that they weren’t exercising imperial rights but rather documenting and reporting the wrongs of the regime, thereby acting for the common good. This is epitomised in the notion of the ‘concerned photographer’, which is also the title of an influential exhibition, one among others in which the figure of the photographer is construed as a hero.

However, in exchange for some of its exclusive rights, not necessarily those that were financially rewarding, photographers have been mobilised to represent those imperial rights as if they were disconnected from the regime of violence. It’s out of this structural denial that the tradition of engaged photography could invent the protocol of the documentary as a means of accounting for objects that were violently fabricated by imperial actors, a mode of being morally concerned among one’s peers.

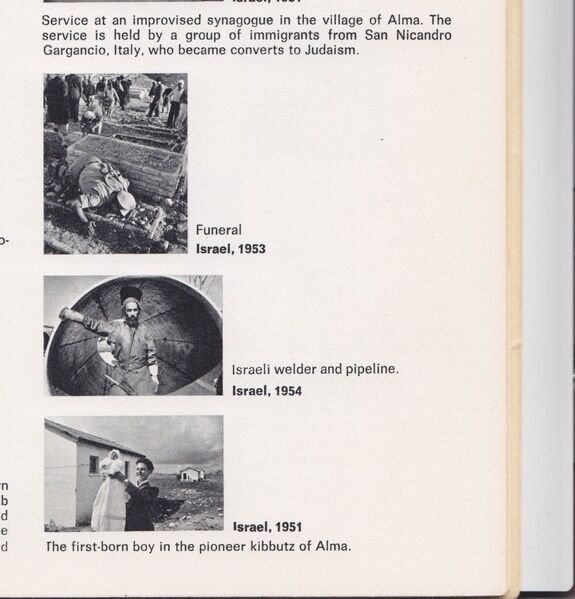

Thus, for example, Magnum/ICP photographers such as David Seymour or Robert Capa could depict the plunder of Palestine as the creation of a new state or world in which Jewish sovereignty could triumph, conflating the plight of the Palestinians with the difficulties encountered by the migrant Jews, who at that point were made guardians of the new sovereignty. Misled by the documentary protocols that they were using, and thus becoming implicated in what was misleading about them, acting as if lived worlds are reducible to their real estate components and nation-building campaigns, these photographers dismiss the plight of the indigenous population as well as the destruction of the common. Differences between situations were blurred in such a way that perpetrators could be depicted as victims or law enforcers even though they were responsible for the destruction of the existing world and the plight of others.

These three 1956 photos taken by Burt Glinn in the same place—a destroyed Palestine, or the newly declared State of Israel—and shown last year in Paris were displayed only with their minimalist original caption: ‘Palestinian Prisoners’. Both the display and the captions take the imperial narrative for granted and assume that there’s no harm in reiterating it nor any need to question the authority of those who acquired their imperial rights and sovereignty against the Palestinians, whom they expelled from their homes. These Palestinians are not ‘prisoners’. In the photos taken in 1956 in Gaza, they are rather brutalised, either as they attempt to return to their homes or when the Israeli occupying forces invade their homes. Either way, they were expelled from their homeland, Palestine, six years earlier, and when they insisted on their right to return to their homes, they were forced to embody imperial categories such as ‘refugee’ or ‘infiltrator’, which endow modern citizenship with a set of imperial rights to keep them in this role. They were made into the unacknowledged participants in such photographs: those whose spaces have been invaded through the exercise of imperial rights so that their images can continue to circulate, tagged with imperial categories that photographers often use as if they were spokespersons of imperial regimes. Contrary to certain rights that people enjoy within their communities, imperial rights don’t emanate from the community in which people are members, on behalf of their membership, or for the sake of a shared world. On the contrary, such rights are derived from the invasion of others’ communities and the destruction of the worlds in which those others enjoy certain rights. Not surprisingly, these imperially unrecognised subjects reject the meaning of photographs as private property subject to copyright.

Thus, on the website Palestine Remembered, for example, Palestinians insist on the rights they have to these photographs, on their being part of the common, and by using them without permission, they challenge the idea of photographs as objects reducible to private property and owned exclusively. The photographer isn’t the one who expelled them, but as long as his permission to photograph is conditioned by those who did expel them and by the regime they established, his right is not universal but imperial.