After attending the exhibition Grow it, Show it! at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, and then returning to Italy, I found myself carrying a subtle sense of intrigue. Grappling with the broad theme of the socio-cultural significance of hair at the core of the show, I was visited again and again by a few vivid images. These were artworks in which hair took on an autonomous presence, detached from the human body – whether through abstract image compositions or the physical presence of actual hair. The materiality of hair stood out for different reasons: in some cases, through the use of actual strands, and in others, through photographic depictions that divorced hair from its usual context, making it the true focal point.

Hair is widely recognized as a powerful symbol of sensuality and fascination, its erotic charge intertwined with ideological and political significance. Photography, in particular, has played a critical role in shaping cultural narratives around hair and hairstyles, often reinforcing gender norms and social conventions but also serving as a tool of liberation and resistance. This is precisely the focus of the show, which unfolds through artworks spanning a wide range of periods and styles. Yet beneath the overtly carnal nature of our relationship with hair – whether our own or that of others – lies something subtler and more elusive to my eye.

Visiting the exhibition, I realized something: hair occupies a liminal space in our life. It’s part of us, yet not entirely. It plays a profound role in shaping our appearance and identity, but we often perceive it (maybe unconsciously) as external, something that exists above or apart from us, with a life of its own. And paradoxically, this life embraces death. In fact, the visible part of the hair –the shaft – is composed of dead cells, devoid of nuclei or vital functions. We spend much of our lives accompanied by a part of ourselves that is no longer alive. Isn’t it curious that we attribute sensuality and allure to something fundamentally lifeless?

The dynamic shifts when hair is severed from the scalp. Suddenly, we possess it, control it. This lesson is absorbed early in life – many children, for instance, find fascination in pulling out the hair of their peers. Or, to recall my own childhood: I had hair that reached down to my lower back, and when it was finally cut, I vividly remember the hairdresser handing me the thick ponytail. I kept it for years in a bathroom drawer, treating it like a hidden treasure. Every time I opened the drawer to look at it, I experienced a strange, unfamiliar pleasure.

Annegret Soltau, Meine verlorenen Haare [My lost hair], 1977

Looking at the works exhibited in Essen, a piece emblematic of this peculiar and visceral tension – one that kept resurfacing in my mind after the visit – is My Lost Hair by Annegret Soltau, a German artist who frequently explores intimate processes such as sexuality, pregnancy, birth, illness, and violence. The installation features a 365-page diary documenting Soltau’s hair loss, with small bundles of hair affixed to the centre of typed and dated pages. Encased in plastic folders, these pages offer a subtle yet profound reflection on aging, change, and the inability to control one’s physical body. The installation at the Museum Folkwang includes twelve folders of collected hair alongside eleven vintage silver gelatin prints. While the work focuses on aging, the visceral presence of hair underscores the artist’s tangible, complex relationship with her own body and the contradictions that characterise our attachment to hair: an illogical, sensual, trivial, dependent, and yet simultaneously repelling relationship.

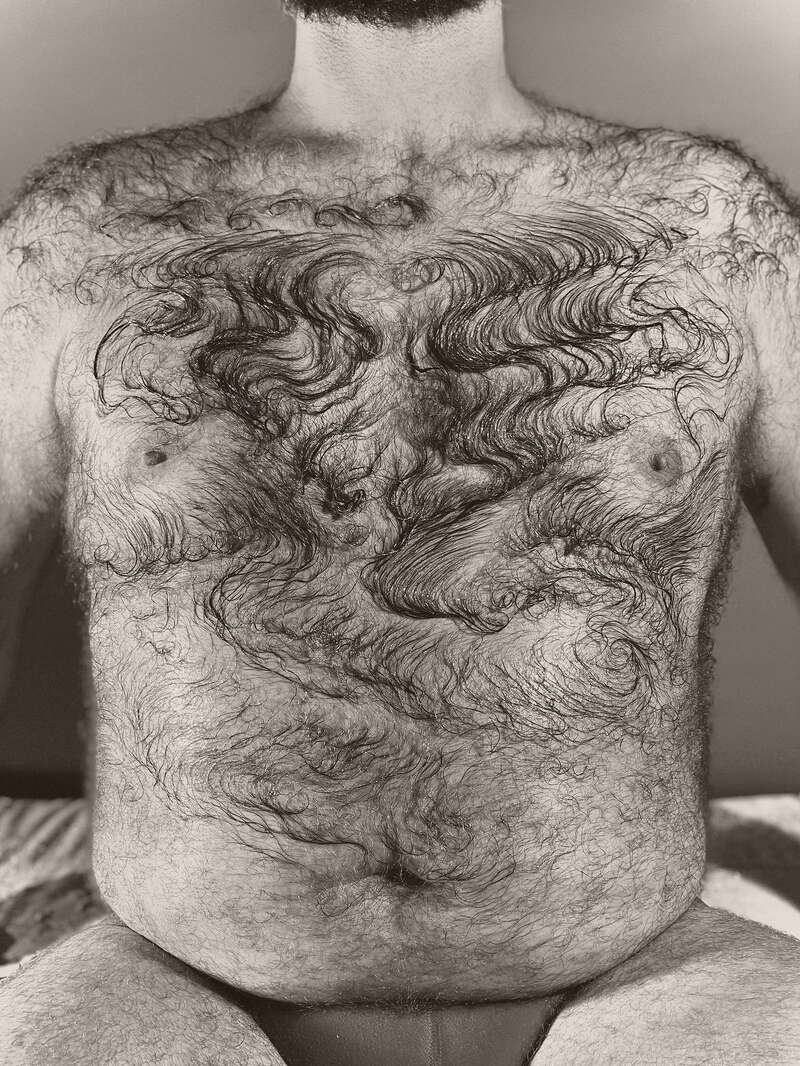

Mona Hatoum, Van Gogh's Back, chromogenic colour print, 1995 © Mona Hatoum

On a completely different note, another artwork that goes back to this gut connection is Mona Hatoum’s Van Gogh’s Back, a photograph imbued with a strong sense of eroticism. The Palestinian artist frequently engages with hair in her practice, using strands detached from the body to create works that momentarily strip it of its cultural and identity-related connotations. Hair, in her installations, often becomes a symbolic totem, sparking visceral reflections on desire and rebellion, and the seductive power of freedom. In Van Gogh’s Back, Hatoum captures the soapy back of a man whose body hair curls into intricate shapes, reminiscent of Van Gogh’s swirling skies. Here, the hairs transcend their socio-cultural associations, losing their figurative quality to evoke an everyday intimacy – a quiet prelude to eroticism.

Lastly, a very small piece of art continued to haunt me in the days after my visit: a small frame containing a black-and-white portrait of a woman, dating back to 1900, surrounded by a wreath of real hair with floral patterns, all carefully under glass. I couldn’t find more information about this little treasure in the show, but upon searching for it online, I discovered that this was a widespread Victorian custom: hair wreaths were composed with the hair of the deceased – or the beloved – and formed into minute decorations. It’s said that the top was left disconnected, as in the exhibited piece, to symbolise the ascent to heaven. This precious gem seems to encapsulate the entire focus of the exposition – or better, of my own interpretation of it. If – as Susan Sontag wrote – photography ‘shows the sex appeal of death’In the introduction to Portraits in Life and Death. Photographs by Peter Hujar; essays by Susan Sontag and Benjamin Moser, Liveright, 2024. , this single work definitely brings together the seductive allure and the inevitable connection to death that hair and photography have in common.

The exhibition 'Grow it, Show it! A Look at Hair from Diane Arbus to TikTok' at Museum Folkwang in Essen runs till 12 Jan 2025.