"In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it." - Jorge Luis Borges, On Exactitude in ScienceJorge Luis Borges, On Exactitude in Science (1946), trans Andrew Hurley.

To access the screening room at London’s LUX gallery, you must first walk through a small library space, as if to make the point that you can’t access the moving image without first passing through the written word. I watched Black Beauty (2021) lying on a carpeted floor, my head and shoulders resting on a giant cushion (Grace Ndiritu has strong theories about how the mode in which we experience an artwork or artefact influences our engagement with it.) A glamorous African actress in incongruous eveningwear stands in full sunlight in a barren quarry landscape while a film crew cajole her through a few lines of banal script endorsing a climate-change-proofed moisturiser with SPF 5000. Environmental concern is re-packaged as a luxury consumer product, and Black skin as a commodifiable aspiration.

Black Beauty, one channel film installation, commissioned by Artscouncil England, Kunstencentrum Vooruit, Belgium, Coventry Biennale of Contemporary Art and Nottingham Contemporary Arts Center © Una Presencia and Post-hippie Productions

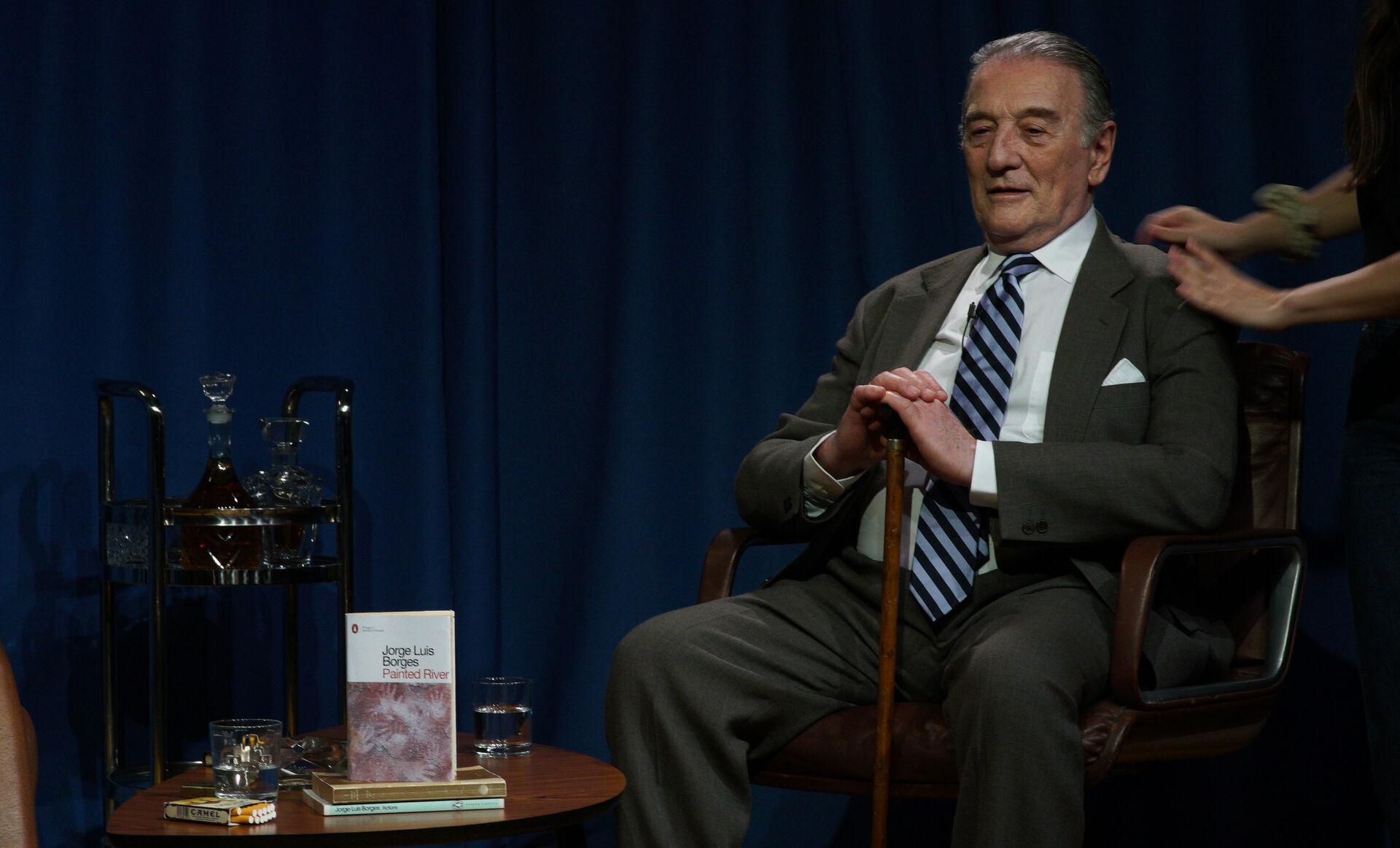

The same woman then appears as the host of a 1980s TV culture show, in conversation with the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. She is smart. He, affable company. While she smokes a cigarette, they discuss Borges’s new book Painted River which traces the African roots of South American culture (and, by extension, all culture) from the ancient cave paintings at Cueva de las Manos. The setting, and even the color grading of the television show make it feel plausible. This is the kind of long-form intellectual discussion that no longer happens on TV, certainly not in the UK. It evokes a certain nostalgia for those of us in the art world. It's easy to get sucked in.

Passing back through the library after the film was over, I stopped to explore a handful of books linked to or influential for Black Beauty, arranged on one of the library shelves. Painted River appears just as it had in the film: a Picador paperback with a cover photograph of the ochre handprints that give Cueva de las Manos its name. I hadn’t read Borges for a while but had started coming back to his work; most recently, I’d read The Circular Ruins while writing about the work of Fiona Tan. But I had not heard of Painted River. Yet when I picked the book up, the cover turned out to be a loose sheet of printed paper wrapped around a volume that was not by Borges. Such are the limits of my knowledge – or perhaps the extent of my credulity. The book, discussed for the duration of a fantasy TV interview, is itself a fiction, and as a work of art the film expanded to take in a portion of the adjacent library. In this instance, it turns out that you can’t access the written word without first passing through the moving image.

Before we move on to explore A Quest For Meaning, we can gather some thematic threads from the experience of watching Black Beauty that might help us approach Ndiritu’s ever-expanding, ever-morphing photographic project.

The first of these themes is interconnectedness. No one aspect of this artist’s multifaceted work is easily separable from the rest: the auditorium will always be linked to the gallery, the archive and the library, but also to the kitchen, the fashion runway, the second-hand furniture store, the blogosphere and the ashram. This essay was commissioned to accompany the installation A Quest For Meaning at FOMU (museum of photography in Antwerp) and an exhibition in which Ndiritu extends that encyclopaedic work’s organising principle to the museum’s own collection. So we are approaching Ndiritu from the arena of photography, but we can’t and shouldn’t attempt to keep her here. In a philosophical sense, interconnectedness underpins Ndiritu’s whole enterprise: her nomadic lifestyle takes her deep into communities around the world. Her privileged status as an artist allows her to ask questions, befriend people and participate in events in a direct and unmediated way – in other words, to make connections.

In this roving, inquiring life, Ndiritu’s interest often lies in finding links across cultures: practices, rituals, symbols and stories that echo and parallel each other across thousands of miles. The video A Week in the News: 7 places we think we know, 7 news stories we think we understand (2010), presents a more banal vision of global ‘hotspots’ as a counterbalance to the sensationalised versions seen on the evening news. Ndiritu invites us to appreciate the relatable ordinariness of places – Darfur, Haiti, Afghanistan – that are usually only shown to us at their worst. Kids play in the street, people drive home from work, sometimes there’s a beautiful sunset; but none of that is news.

The second theme in Black Beauty that also underpins much of Ndiritu’s work is the question of faith. Ndiritu often invites us to have faith in her – through her experiments in alternative modes of living and working, as well as in the shamanic rituals she performs.. In asking for our faith, Ndiritu also reminds us not to give it blindly: as we see in Black Beauty, she’s a trickster. This double edge invites us to question what we see (an important skill when dealing with photography) as well as the systems that we place our trust in. Faith also appears in Ndiritu’s work in the more specific sense of belief in a higher power. Whether it’s the Christian heritage that underpins Theaster Gates’s social practice, or the Tantric philosophy informing Harminder Judge’s meditative sculpture, public expressions of faith are increasingly accepted in the artworld, whereas for decades this was not the case. For the last twenty years, Ndiritu has asserted the spiritual dimension of her work and presented her art practice as inseparable from her spiritual practiceI think this throws an interesting light onto the way we use the term ‘practice’ in the artworld. It’s a word that can invite ridicule and which some regard as pretentious, but I think it becomes more useful when understood in yogic or Buddhist terms: your daily practice is what you do, the expression of your worldview as applied to the business of living. ‘Practice’ also suggests the acquisition of knowledge, insight and skills as an ongoing process – who we are and what we do is never finished, one thing leads to the next, there is always more to come.. In so doing, she has often felt at odds with the contemporary art world.

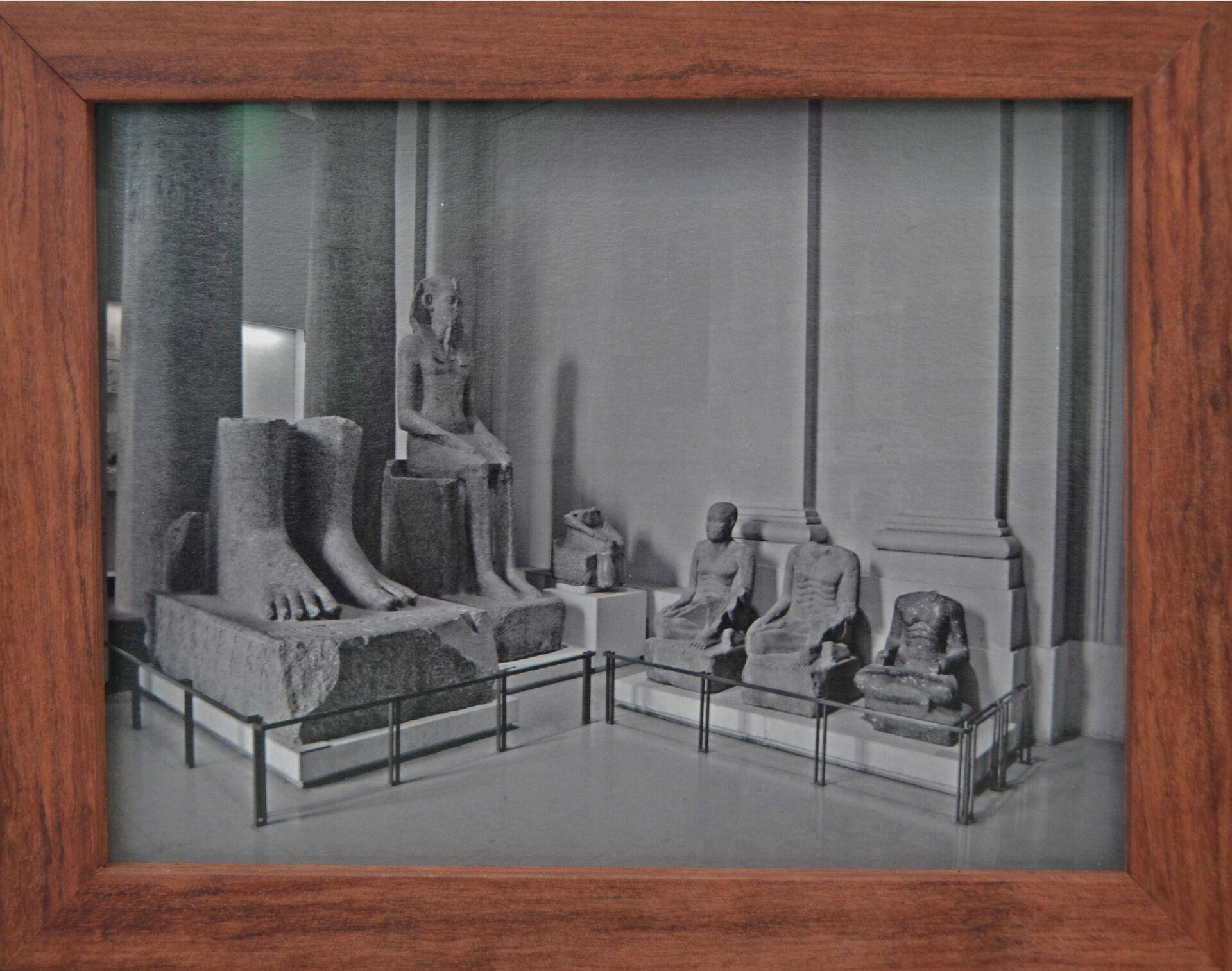

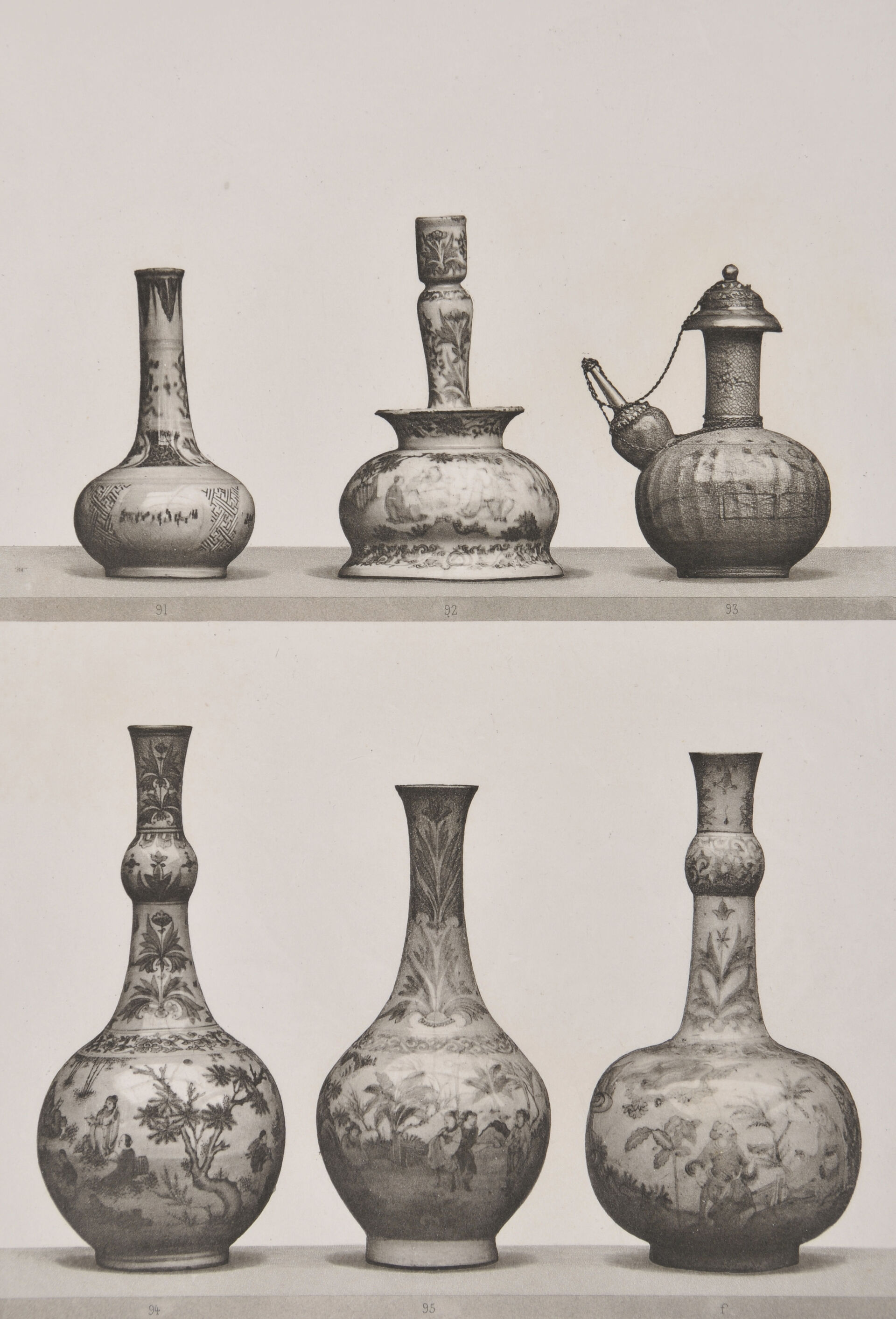

The third theme is Ndiritu’s interest in challenging established structures. In Black Beauty, this is manifested in the unconventional, even jarring form of the film itself, as well as in the artwork’s expansion into the wider spaces of the gallery – the relaxed seating, the books in the library, a small publication. Where does art end and life begin? Why even try to make the distinction? In her ongoing project Healing The Museum (2012-), Ndiritu also invites us to think about the structure of museums, libraries and archives in general, and the worldview that informed the collecting, documenting, naming and categorisation of the objects that fill our great institutions. So much is bound up in the apparently simple distinctions – between nature and culture, for example, or between art and artefact – that determine whether an object might be placed in a museum of natural history, ethnography, decorative or fine arts.

With Healing The Museum, Ndiritu is one of a number of artists over the last decade to explore collections and the value systems informing them. In her acclaimed video work Grosse Fatigue (2013), Camille Henrot attempted an overview of the different ways humankind has sought to explain the world, drawing a connecting line between creation myths, the archives of the Smithsonian Institution and the artificial intelligence powering the Google search engine. We can look, too, at the work of Fiona Tan, and works such as Inventory (2012) and Depot (2015), filmed in Sir John Soane’s Museum in London and among the jars of specimens in two European Natural History archives, respectively. The latter work specifically identifies the violence involved in naming and classifying things and the casual assertion of ownership that accompanies it.

Ndiritu goes further, evoking the animism of many non-European religions as well as the anti-hierarchical worldview proposed by object-oriented ontology to imagine the museum archive as a site of imprisonment, where objects are torn out of their context, cut off from their intended (or inherent) purpose. Here, the structure Ndiritu questions is foundational to the whole museological project: our understanding of what is animate and what is inanimate. As philosopher Jane Bennett suggests in Vibrant Matter (2010), the answer is far from simple, and we ignore non-human forces at our peril.

The fourth key theme in Ndiritu’s work that we can draw from Black Beauty

is conversation: that simple phenomenon through which human relationships are expanded, knowledge shared, bonds formed and disagreements reconciled. It is also, in this era of social media spats, apparently a dying art, though not where Ndiritu is concerned. Her book Dissent Without Modification (2021) is a series of seven conversations – some revolving around social activism – conducted at different locations around the world with women who have led unconventional creative lives.

There is a crucial distinction to be made between an interview and a conversation. An interview is asymmetrical – there is a questioner and a respondent: the flow of information is one-way, and the interviewer is sometimes of no interest to the interviewee. A conversation is ideally non-hierarchical and involves an exchange of views. Unlike, for example, Hans Ulrich Obrist’s long-running series of artist interviews, Ndiritu’s extended dialogues are conversational: there is an exchange of ideas and even room for disagreement. Thus we might see the Black intellectual sitting in the host’s chair in Ndiritu’s film as an avatar for the artist herself: an interested and opinionated woman.

Ndiritu creates other kinds of conversations in her work. The Ark – a ‘post-internet living research/live art project’ created by Ndiritu with a group of volunteers at Les Laboratoires Aubervilliers in Paris in 2017 – was, at its heart, an experiment in conversation, both between the participants themselves and between them and their environment. It positioned conversation as a generative force, a practice that could bring about meaningful change.

In questioning the structures of museum collections and archives, the artist also creates the conditions for a non-hierarchical exchange between objects and images with very different points of origin. A Quest For Meaning is structured around a series of conversations between images that have been placed in one another’s company according to an intuitive classification system. The framing device for the work is a conversation between three extraordinary women, each in her own way a totem of modernism, but whose paths never crossed (to my knowledge): photographer Tina Modotti, painter Georgia O’Keeffe and fibre artist Anni Albers.

A Quest For Meaning is an encyclopaedic endeavour – the story of the universe since the Big Bang told in photographs. It is a project without end. In this era of Deep Time, the nanosphere and the James Webb Space Telescope, the sheer number of images required to complete it make Borges’ map seem like a comparatively reasonable proposition. You might describe it as an enterprise doomed to fail, but we shall fall into step with the poet C.P. Cavafy as he urges us, in Ithaka: ‘don’t hurry the journey at all. / Better if it lasts for years’. If we race toward our Ithaka, we will lose out on our Odyssey; instead, we must thank the destination for the gift of the journey. A Quest For Meaning is not meant to be completed. Rather, it proposes various ways we might see the world differently, imagines new categories for arranging an archive (in this case, the actual collection of FOMU) and transforms the museum environment in which we view, contemplate and experience photography.

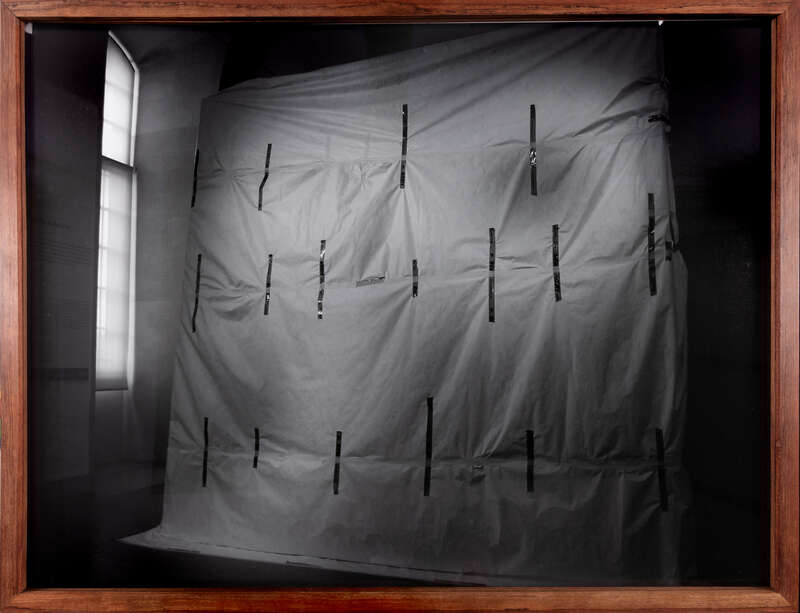

A Quest For Meaning was first realised in 2014, at MACBA in Barcelona. Ndiritu had taken part in a research residency at L'appartement 22 in Rabat, Morocco, during which she photographed archival documentation of the 1920s Rif War between the occupying Spanish and the Berber people. Thinking about political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s proclamation on the end of history, writer William Burroughs’s cut up method, and the cinema of Ahmed Bouanani, Ndiritu asked at the time: ‘Is it possible for a quest for meaning to be found through a single work of art?’Grace Ndiritu, AQFM Periodical Volume #1 (Barcelona : MACBA, 2014).This first version of the encyclopaedic project was shown in a rather formal presentation at MACBA, the images positioned in specially designed African bubinga wooden frames and loosely clustered around sections of the wall painted in pastel colours. Each colour denoted a different theme: lilac for travel and plants, lemon for still lives and animals, pale blue for modernist interiors and exteriors. For the most part, the photographs were abstract, showing patterns and details of architecture and plants. There were no captions that might have revealed what we were looking at or where the photographs had been taken. Instead, temporary constellations of diverse geographies and histories coalesced in the gallery. Without relying on labels, the viewer was left to make their own connections between the images and construct their own narrative. This is the version of A Quest For Meaning now in the FOMU collection (purchased by the Flemish Community in 2021), but there have been others.

For the second incarnation of the work, at La Ira de Dios in Buenos Aires in 2014, the photographs were presented as paper photocopies that formed the backdrop to a rave – an event that honoured the use of the word ‘trance’ in both a spiritual and a musical context. In this version, Ndiritu paid tribute to the German art historian Aby Warburg – referencing both his own encyclopaedic project the Mnemosyne Atlas and to his immersion in the culture of the Native American Hopi tribe (a culture with which Ndiritu herself is acquainted). Warburg’s portrait was projected on the warehouse wall during the rave.

The search for a totalising theory – a comprehensive system, a key to all things – is an ancient quest. It is also a metaphor for hubris. In George Elliot’s novel Middlemarch (1871–72), Edward Casaubon – the pompous, controlling husband of the clever heroine Dorothea Brooke – dedicates his life to composing a Key to All Mythologies. It is an impossible task, one that Dorothea fears she will be legally compelled to complete after her husband’s death. Read through a postcolonial lens, Casaubon could also be seen as embodying a nineteenth-century mindset in which an English theologian assumes that he can become master of everything worth knowing and exert control through cataloguing and systematising.

Grace Ndiritu Reimagines the FOMU Collection FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

Grace Ndiritu Reimagines the FOMU Collection FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

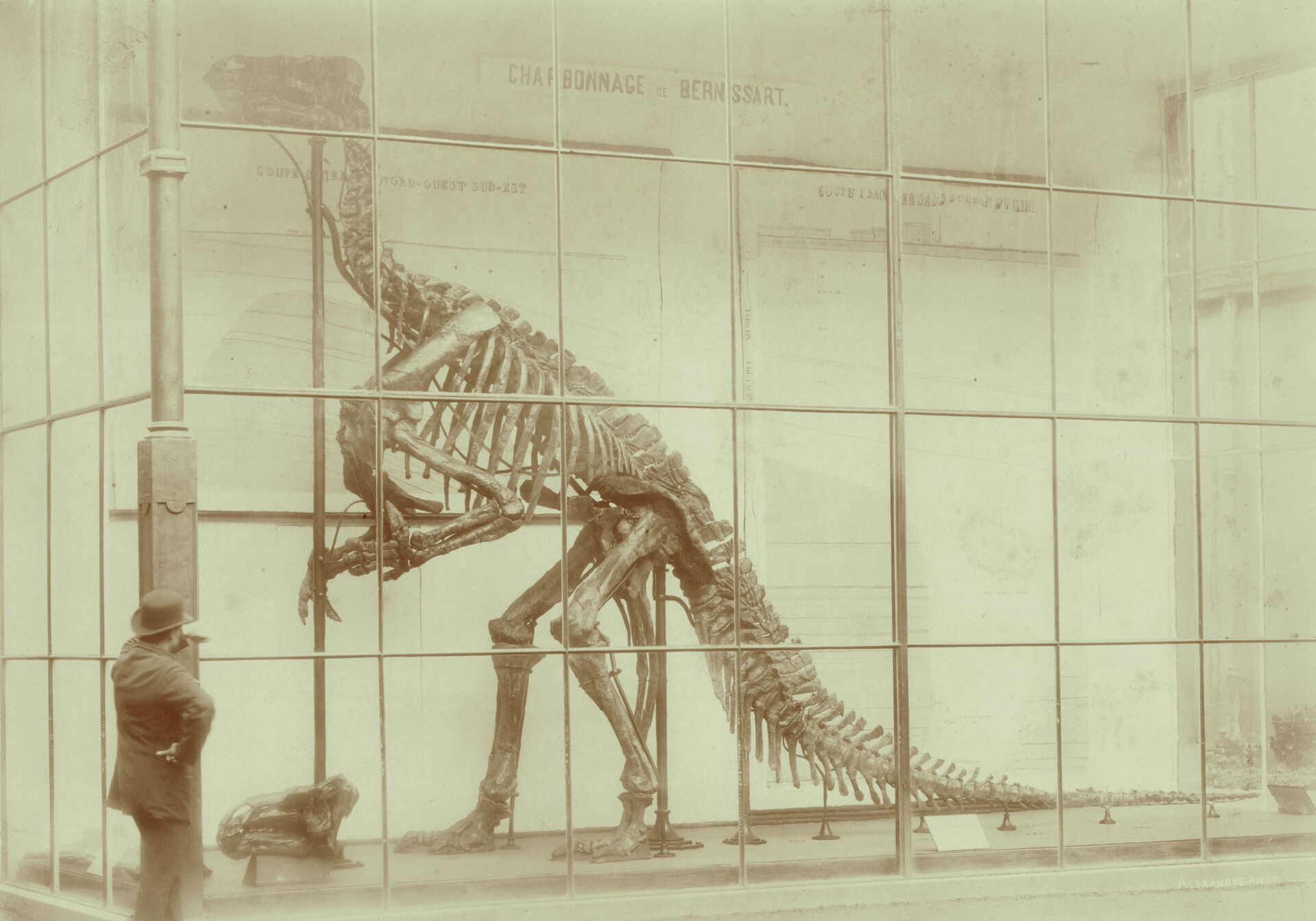

A real-life attempt to build a comprehensive knowledge system of the world took place in Belgium at the turn of the twentieth century. The work of lawyers Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine, it became known as the Mundaneum and was housed in one of the wings of the Palais de Cinquantenaire in Brussels. Otlet and La Fontaine built up an archive of more than twelve million index cards, arranged according to their own Universal Decimal Classification system. There were grand ambitions for the Mundaneum, which was imagined as a source of world knowledge open to all, an instrument of world peace to be housed in a building designed by the modernist architect Le Corbusier. It turns out this unruly world of ours is highly resistant to being jammed into rational systems and tends to spring out of our grasp. What remains of the Mundaneum, and of its curators’ organising diagrams, is now housed in a museum in Mons.

Ndiritu’s Quest For Meaning is a riposte to the rigid logic systems of the European Enlightenment. As such, it sits within an artistic tradition of image-gathering and cataloguing that includes Gerhard Richter’s ongoing Atlas, Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s Sichtbare Welt (1997) and the pictorial assemblages of Hans-Peter Feldmann.

A distinguishing feature of Ndiritu’s encyclopaedic project is the guiding role played by non-rational states of mind, such as dreams, trips and visions. These phenomena of the human brain were privileged by earlier generations, from the Aurignacian artists of the Chauvet caves to mediaeval mystics like Julian of Norwich, and remain important within alternative and indigenous cultures. The idea for the work came to the artist during a shamanic journey in which she was transported to the cosmic ‘upper world’, where she found herself able to visually zoom in and out of planetary systems, an experience she subsequently likened to the action of a camera. Her account of this experience recalls Charles and Ray Eames’s film Powers of Ten (1977), which used photography to show the relative size and distance of things in the known universe, from the dark space beyond our galaxy to the proton of a carbon atom.

The clusters of photographs in A Quest For Meaning can thus be likened to constellations: groupings of loosely related stuff that takes on greater meaning through its relationship to other stuff. We might also imagine the work in its totality as a kind of journey, akin to Ndiritu’s shamanic vision, in which the mind can travel freely over great distances while the body remains in one place.

As well as exploring how a museum or archive might embrace different kinds of thought, Ndiritu addresses the relationship between the institution as an architectural entity and the physical body of the visitor. This relationship has traditionally been subject to an unspoken hierarchy: the museum object is to be cherished and protected. The visitor passing through the body of the museum follows strict rules (no touching, no flash photography, no large bags) as well as an unspoken behavioural code (no loud talking, no laughter, no fooling about). In blockbuster exhibitions, visitors are expected to file compliantly through galleries in a snaking line; attempts to linger or backtrack, or inadvertently blocking the view of an artwork by prolonged contemplation, mess up the system. Many social groups experience museums and galleries as hostile spaces. Young people and people of colour visiting European museums have found themselves followed closely by museum guards.One recent anecdote I’ve heard concerns the MMK (Museum für Moderne Kunst) in Frankfurt.Anyone displaying unconventional behaviour is likely to be the subject of glares and complaints.

In the UK, Steve McQueen’s Year 3 project was a grand gesture aimed at breaking down the sense of exclusion many feel when faced with a grand neo-classical gallery. In 2018, McQueen invited every Year 3 pupil (children aged between seven and eight years old) in London to have their photograph taken: seventy-six thousand students were snapped, and their class photos displayed around the city on billboards as well as in the grand central Duveen Galleries of Tate Britain. The message was one of welcome – the children were invited into the museum to find themselves, bestowing a sense of ownership and comfort within the institution to a whole generation of children. McQueen negotiated with Tate to ensure affordable food would be available in the cafeteria, and a special learning team was hired to greet school groups.

Year 3 was cut short by the pandemic. Among other impacts, Covid-19 has created a new barrier to entry for our public museums in the UK: visits must now be booked ahead online. Staff cuts have greatly restricted museums’ educational provision. With visitor numbers reduced, school trips will be rarer. It is imperative to counterbalance this regressive tendency if we wish to defend cultural institutions as spaces open to all. In Ndiritu’s Healing The Museum, the reparative gesture is twofold, aimed not only at the archive and modes of display but also at the way the visitor is received in the institution and the kind of behaviours it might accommodate. Placing a shamanic ritual in an institutional space is akin to a gesture of rewilding, suggesting the possible re-animation of once vibrant relationships between visitors and archival objects.

In applying the methodology of A Quest For Meaning to FOMU’s collection, Ndiritu transforms the gallery into a common room: a space that invites visitors to sit down, linger, read books, converse and perhaps even rest (for why should the state in which we encounter art be one of active work? Why not a dream space?) The furniture, forms and colour all take inspiration from the mid-century movement – part of Ndiritu’s ongoing interest in modernist architecture and design, apparent also in the wooden structure she created for The Temple at Nottingham Contemporary in 2022. Drawing on images from the FOMU collection, Ndiritu used blown-up photographic details – of woven and sculptural patterns that fascinated Anni Albers, or Georgia O’Keeffe’s homes in Abiquiú, New Mexico, or architectural details photographed by Tina Modotti – as wallpaper within the exhibition space. These women, who lived, as Ndiritu might say, ‘without modification’, act as spirit guides for the show.

Grace Ndiritu Reimagines the FOMU Collection FOMU Antwerpen © We Document Art 2023

Modotti had a portmanteau career of a type that seems peculiar to the early twentieth century. After moving to San Francisco from Italy at the age of sixteen, she found employment as an actress and model, appearing in silent movies in the 1910s. She came into photography through her romantic relationship with Edward Weston, with whom she ran a studio in Mexico City, becoming a fixture within that city’s bohemian avant-garde. In her own photography, Modotti explored the experience of Mexico’s workers, the matriarchal society of Tehuantepec and emblems of revolutionary progress. A member of the Mexican Communist Party (along with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo), she was seen as a dangerous subversive force in the political sphere and was falsely accused of ordering the assassination of her lover, the Cuban activist Julio Antonio Mella. She died, aged forty-five, under what some considered suspicious circumstances.

Albers entered the weaving workshop of the Bauhaus in 1922 – a milieu dominated by women, since they were barred from the study of painting even at that progressive institution. The rise of Nazism that forced the closure of the Bauhaus also drove Albers and her husband Josef to migrate to the US, where they were foundational in the establishment of a radical new art school, Black Mountain College. Located in rural North Carolina, the college was non-hierarchical: students and teachers alike worked together to run the institution and contributed collectively to the creative milieu. Anni Albers’s new life in the US gave her the freedom to travel widely in Central and South America, during which journeys she accumulated an archive of important textiles and fragments and learned local weaving techniques. At Black Mountain, she taught students to weave on a back-strap loom. A simple apparatus with which a weaver can produce long bolts of cloth the width of their own body, it is a tool found in many cultures around the world, from indigenous communities in Mexico to women weaving in the markets on the edge of the Karakum desert in Central Asia.

Born in 1887 to a large farming family in Wisconsin, Georgia O’Keeffe experimented with abstraction early in her career and entered into a liberated relationship with photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz. The couple collaborated on a series of intimate photographs of O’Keeffe’s naked body – including studies of her hands, skin and torso – some of which were publicly exhibited by Stieglitz in 1921. Painting abstracted views of New York’s skyscrapers and zoomed-in studies of flowers (inspired by recent developments in photography) O’Keeffe’s reputation gradually outstripped that of Stieglitz. After moving to New Mexico in the late 1940s, she became synonymous with the mountains and wild landscapes of the state. Her home in Abiquiú dates from the eighteenth century and was renovated using traditional adobe (mud brick) techniques. The cool modernist interior was decorated with stones, shells, bones and weathered wood: natural forms that we might consider art without artists. Bridging the ancient and the modern, and constructed using sustainable materials (left untended, adobe will eventually melt back into the earth), O’Keeffe’s home triggered a specific sensory connection in Ndiritu, who linked it to her grandmother’s adobe house in Kenya.

Offering these three historic figures as guiding spirits to A Quest For Meaning Ndiritu offers a view of modernism through the lens of women’s endeavours and achievements. In life as in art, each was a roving, curious, independent spirit, who at times fell afoul of social conventions. It’s a gesture that invites us to reconsider our preconceptions about who took the photographs that make up the constellations in both A Quest For Meaning and the curated display from the FOMU collection – perhaps not all the photographers of these images are male? We might also go on to ponder the intended purpose of these photographs – were they artworks for public display, promoting socialist ideals in post-revolutionary Mexico, as in the work of Tina Modotti? Or were they records destined for a working archive, like the photographs of Anni Albers? We might even start to think about what impact photographs have – can they open up new ways of seeing, as the abstract and focused work of Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand did for Georgia O’Keeffe?

Grace Ndiritu, A Quest For Meaning: Painting as a Medium of Photography, 2014, Collection FOMU / Collection Flemish Community BK/9433 © Grace Ndiritu

As a child, Ndiritu used to imagine being able to change the way people thought. The younger Grace, living in an alternative community with an activist mother, imagined herself growing up and becoming a philosopher. The adult Grace, still living in alternative communities, has taken up the same mission through art. A Quest For Meaning is a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – that has absorbed the work and life experiences of many other artists, as well as the structure and conventions of the FOMU itself. Through it, Ndiritu both celebrates and challenges the collection, offering immersive lived experience, informal conversation and shamanic visions as alternative forms of research.

Ndiritu has provocatively referred to this work as a ‘painting’, a type of expanded photography. Introducing pastel colours, focussing on the furnishing and design of the space and prioritising photographs of natural forms, indigenous weaving and vernacular architecture over representation of the human form, it represents a challenge to the hierarchy according to which different creative enterprises and ‘classes’ of object have been conventionally ordered. Treasures of the natural world were scientific curiosities; Euro-American applied arts were valued above ‘traditional’ artefacts; Renaissance painting and classical sculpture were raised above all, and at the top was man’s heroic likeness.

A Quest For Meaning suggests that there are many ways that we might conduct this titular search. As a work subject to an ongoing process of transformation, it allows us to explore the different ways in which we might draw connections through the world and suggests many different methodologies to which we might turn in doing so. It is an exercise in radical, shamanic, immoderate, inviting, curious and above all non-hierarchical museology. A map through time as well as space, offering no destination.

Editor's Note

This article by Hettie Judah has been written to accompany the exhibition Grace Ndiritu Reimagines the FOMU Collection. FOMU invited artist Grace Ndiritu to enter into a dialogue with our collection, starting from her own artwork A Quest For Meaning. Each year, FOMU asks an artist to become a guest curator, and create an exhibition by diving into the collection. They can make new connections using on their own art and associations.

The exhibition by Grace Ndiritu will be on show from 17 February 2023 till 7 January 2024 and features work by artists such as Alexandre, Bianca Baldi, Samuel Bourne, Dirk Braeckman, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Lynne Cohen, Gilbert Fastenaekens, Gertrude Fehr, Geert Goiris, Willy Kessels, Rinko Kawauchi, Man Ray, Auguste Salzmann, Filip Tas, Nadine Tasseel and Wolfgang Tillmans.

Ndiritu has constructed a totally new photographic universe of painting, textiles, and interior design. Expect a wooden scenography inspired by world’s fairs, mid-century Californian homes, and museum interiors. We invite you to visit the sensory exhibition with an open mind, making intuitive connections.