There are forty-five millions of posts tagged #selfcare on Instagram and ninety in the last hour on Twitter.

Self-care has turned into a bit of a catch-all term. There are various degrees of self-care. There’s practising it religiously as a form of survival, and then there’s the whole thing going adrift. Often instrumentalised in neoliberalist cultures to relieve governments or employers of their responsibilities – transferring the burden of care onto individuals on the pretext meritocracy – self-care becomes less about practising care and more like ‘self-care, don’t care’. In that context, self-care is all about the self as opposed to caring for the other and not simply an act of self-preservation. However, the notion of self-care, one might argue, comes from a good place, and it does do wonders for anxiety. Like a lot of good things, it dates back to the Greeks, but it was also practised by the Romans, then the Enlightenment philosophers, and so on.

By all accounts, caring for the soul and cultivating one’s own garden shouldn’t be selfish acts. In fact, self-care is sold today as a form of self-endorsement, likely to expose you to the vulnerability of others and invite you to care for them. But if we turn to self-care to address our anxieties, aren’t we then spending all our energy sorting out our own issues, instead of correcting the systems causing them in the first place? ‘Sorry, not sorry’ is hardly a place to start to eradicate systemic racism or dismantle the patriarchy. So, can there be a form of self-care that’s good for the self as well as the other?

There appears to be a dichotomy between self-care as an empowering statement and the culture of self-care as performance. Popularising self-care both creates and echoes the dangers of the capitalist trope according to which one is worthy of it (or not). So, the question is: can self-care be a radical form of action, and can it be depicted as such?

The term self-care was repopularised in the 1970s and ’80s by people of colour and queer communities, and perhaps most notably by Audre Lorde, who saw it as granting a sort of permission for self-preservation in a world that confines certain people to hardship and precarity: ‘I had to examine … the devastating effects of overextension. Overextending myself is not stretching myself. I had to accept how difficult it is to monitor the difference. Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.’Audre Lorde, A Burst of Light (New York: Dover Publications, 2017; Ithaca, New York: Firebrand Books, 1988), 227. Written just after she was diagnosed with breast cancer, the text grounds frameworks that go against the neoliberal rules by which exhaustion rhymes with excellence and vocation rhymes with abnegation, inscribing self-care into a politically radical approach.

Similarly, after being diagnosed with breast cancer, Polish artist Alina Szapocznikow started to work with her own body as a cast for her sculptures, in order to convey that ‘of all the manifestations of the ephemeral, the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of all joy, all suffering and all truth’Charlotte Higgins, ‘Body shock: the intense art and anguish of sculptor Alina Szapocznikow’, The Guardian, 6 October 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/oct/06/human-landscapes-body-shock-the-art-and-anguish-of-sculptor-alina-szapocznikow. – as if self-care were a biproduct of reappropriating the body rather than the other way around. These notions are also mirrored in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study,Stefano Harney and Fred Mote, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), 120: ‘Recently, I’ve started to think more about elaborations of care and love.’ a series of essays on the theory and practice of the Black radical tradition and the ramifications of debt and credit on how we understand our place in the world. Looking after ourselves can never be a priority because we’re already too invested in the things that corrupt our time and free will.

Still from Soft Film, 16mm film on video with sound, 6’ 28 sec., 2016. © Sara Cwynar, courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production, New York

Still from Soft Film, 16mm film on video with sound, 6’ 28 sec., 2016. © Sara Cwynar, courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production, New York

At the same time, the performative forms of self-care seem more tangible (i.e., perceptible) than deeper forms of self-work: have you tried yoga and meditation? — rather than the existential prospect of not straining oneself. Failing to look after yourself means failing to meet your own needs and be deemed a responsible adult. ‘What can you do with no time and no money?’ asks the narrator in Sara Cwynar’s video Soft Film,Quoted in Sheila Heti, ‘Should Artists Shop or Stop Shopping?’, Affidavit, 21 May 2018, http://www.affidavit.art/articles/shop-or-stop-shopping. amidst a barely intelligible sea of words quoting the injunctions that dictate our anxieties. When we look at self-care, we tend to idealise it through a warped lens. Self-care isn’t about achievement, ticking boxes, being successful.

In a 1982 lecture that became an essay called Technologies of the Self, French philosopher Michel Foucault aims to revive the ancient notion of self-care (epimeleia heautou, literally ‘care of the self’), arguing that looking after oneself is a kind of ‘vigilance’ that dates back to antiquity. According to Foucault, in Ancient Greek philosophy, ‘taking care of yourself eventually became absorbed into knowing yourself.’Edited by Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, Patrick H. Hutton, Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 30.

But what does knowing yourself mean, and how do we practise it? Today, the Christian value love thy neighbour as thyself might as well be something along the lines of love yourself as you wish you were loved, in accordance with the contemporary desire for fulfilment and obsession with pursuing happiness. The original notion implies that there is self-love to begin with, and that it’s a source of power that ultimately brings us together. However, self-hatred is one of the core symptoms of depression, and the World Health Organization estimates that around five percent of adults worldwide, or approximately 280 million people, suffer from depression.

Self-care is basically vital. When, at the end of every episode of Ru Paul’s Drag Race, Ru Paul famously asks ‘if you don’t love yourself, how in the hell are you gonna love somebody else — can I get an amen up in ‘ere?’, he’s addressing the importance of self-love as a radical act of survival for the queer community, preaching it like a sermon to connect it back to its religious roots, seeing self-care as intrinsically linked to the care of the other. But the thing is, we’re so dispossessed of our ability to look after ourselves properly that we don’t know how to do it anymore. It’s systemically made impossible for us— because not everyone is worthy of it, because it’s counterproductive, because we’re doing it wrong, because we’re doing it for the wrong reasons.

The theme of self-care is ubiquitous today, but interestingly, it doesn’t always go hand in hand with talking about mental health in an upfront way. For example, Kit-Kat ads praise the art of taking breaks for yourself but would never breach the treacherous path of burnout. Why would they? Burnout doesn’t sell. Pop culture is riddled with references to it, though: artists from Solange‘Borderline (An Ode to Self Care)’, track 14 on Solange, A Seat at the Table, Saint Records/Columbia, 2016. to Mac Miller‘Self Care’, track 5 on Mac Miller, Swimming, REMember Music/Warner Bros., 2018. have named songs after it, and comedians like Hannah GadsbyMadeleine Parry, dir. Nanette. Netflix, 2018. https://www.netflix.com/title/80233611;

Madeleine Parry, dir. Douglas. Netflix, 2020. https://www.netflix.com/title/81054700. and Bo BurnhamBo Burnham and Christopher Storer, dirs. Make Happy. Netflix, 2016. https://www.netflix.com/title/80106124;

Bo Burnham, dir. Inside. Netflix, 2021. https://www.netflix.com/title/81289483. – both streaming on Netflix and therefore available to the widest possible range of audiences – are breaking down the boundaries of the many, many taboos around mental health.

But what good can come of taking care of yourself, really? In her video Chaos Disco, which collects footage of dances taken from archives and mainstream media alike, the artist Ina Lounguine asks ‘has the world gone mad?’ in an attempt to understand what connections can be made between the mind and the body in our incapacity to digest the absurdity of the contemporary world and its violence – whether class, gender, or race based. Suggesting that we could dance the horror off suggests a radical form of action, which is to prioritise care against adversity – a form of ‘make love, not war’. Taking care of your body and mind could be, and perhaps should be, a place to start.

Still from It's a Sin, Channel 4, 2021

Still from It's a Sin, Channel 4, 2021

This is where we’re confronted with the impossibility of looking after ourselves, because we’re constantly confronted with how we’re supposed to do it, and our understanding of good and bad informs our fear of failure. And not being able to perform self-care means failure. So we listen to podcasts about failingElizabeth Day, How to Fail, ongoing podcast audio series since 2018. https://howtofail.podbean.com/. and talk about failure like we’re OK with it. Although it doesn’t have a catchy acronym like FOMO or YOLO, the fear of failure is pervasive in our day and age. There are specific kinds of cognitive behavioural therapies to treat atychiphobia, or fear of failure.

But fear of failure isn’t the only ravaging form of universal anxiety. Surviving the COVID-19 pandemic, so to speak, has tested our enduring empathy and ability to exercise self-care by simply making it difficult to go about the world responsibly. We end up negotiating with risk and anxiety and imaginative empathy and hostility, which exhausts us. And it’s been largely overlooked how much the return of a pandemic has been triggering for members of the LGBTQIA+ community who endured the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and had to face the return of forced quarantine and germaphobia.

In It’s a SinPeter Hoar, dir. It’s a Sin. Channel 4, 2021. https://www.channel4.com/programmes/its-a-sin., a series on the crippling doubt and fear that spread around the start of the AIDS crisis in the UK, writer Russel T. Davies strongly emphasises the importance of self-care, as it became one of the first things that people who contracted the virus couldn’t do for themselves, and care was something relatives and medical teams struggled to provide because they were not only ill-prepared but also ill-informed. Hence the resurgence of death doulas.

Making up for the lack thereof, a form of care and empathy is captured by the intimacy so palpable in the work of Nan Goldin, a friend of David Wojnarowicz, who himself spoke of such friendships as ‘emotional link(s) to the world’David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (New York: Vintage Publishing, 1991), 121. In reference to the sickness and death of his lover, best friend and mentor, the photographer Peter Hujar: “my brother, my father, my emotional link to the world”.. Goldin captured moments where hope collapses into despair, moments where self-care is no longer possible.

Wojnarowicz’s fight for the rights of AIDS sufferers also inspired Rosa von Praunheim's widely acclaimed film Silence = DeathRosa von Praunheim, dir. Silence = Death. First Run Features, 1990., on the responses of New York City artists to the AIDS epidemic. The film is titled after the militant, awareness-raising group of the same name, who were famous for instigating the concept of mutual support in the context of the crisis. It also inspired Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (for David), which consists of hundreds of spoiled fruit skins that the artist stitched back together with brightly coloured thread and wire. All these pieces can be perceived as activist work, but are, in fact, a way to offer a form of care for the bodies that weren’t able to perform it, the bodies that weren’t offered it.

In an article for The New Yorker, Jordan Kisner writes that ‘“self-care” is newer in the American lexicon than “self-reliance,” but both stem from the puritanical values of self-improvement and self-examination.’Jordan Kisner, ‘The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care’, The New Yorker, 14 March 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-politics-of-selfcare. We’re made to believe that the only risks of self-care are biting the hand that feeds us, or appropriating a practice of self-preservation that’s not appropriate for our class, gender, or race. But ‘when you endorse yourself as both vulnerable and worthy, especially when that endorsement feels hard, you can grant that same complex subjectivity to others, even to people whose needs and desires are different from your own.’Jordan Kisner, ‘The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care’, The New Yorker, 14 March 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-politics-of-selfcare.

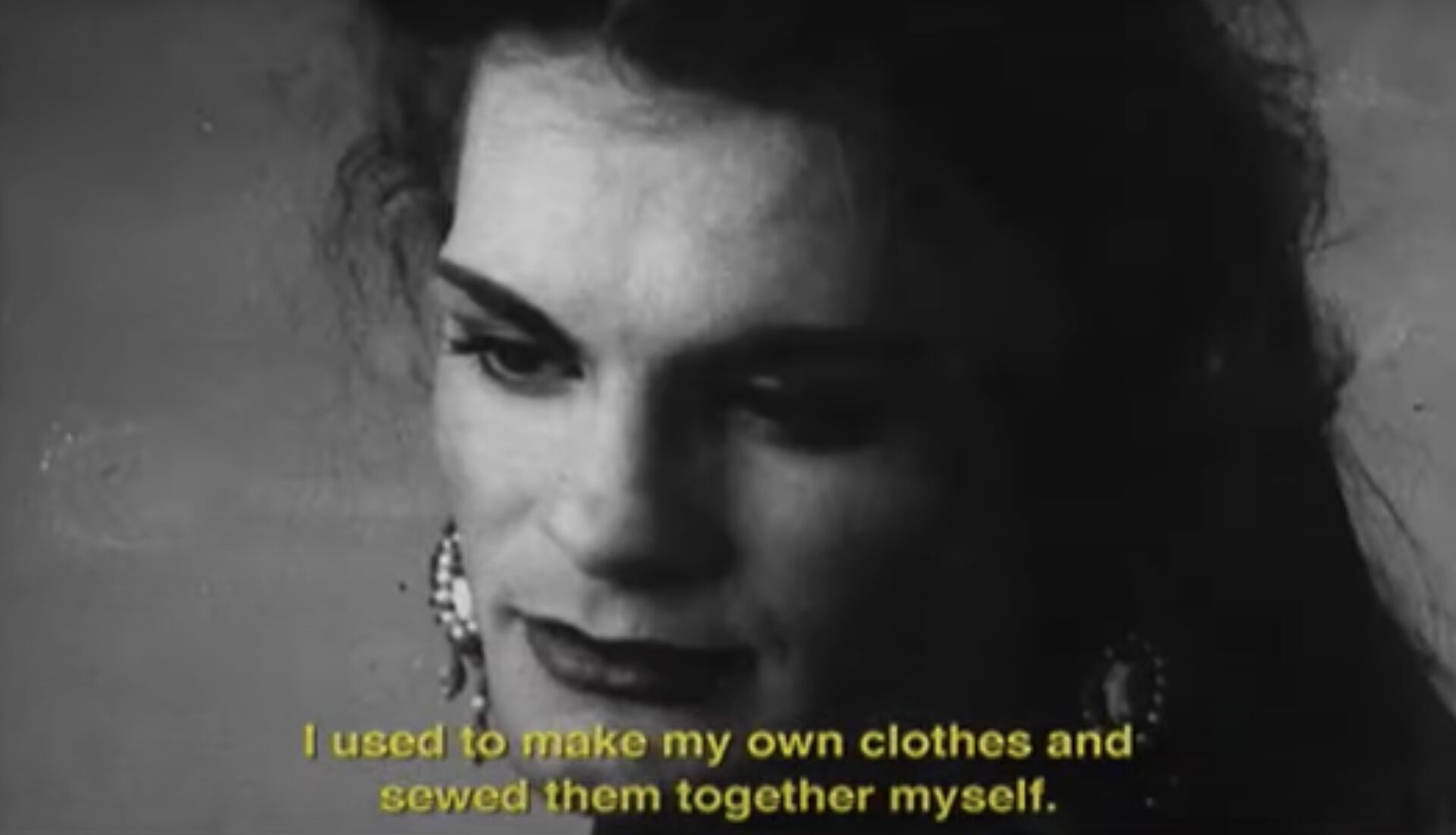

Still from Lorenza: Portrait of an Artist. Directed by Michael Stahlberg, 1991.

This school of thought is very present in the work of Lorenza Böttner, for instance, who was firmly opposed to the processes of de-subjectification, mentoring, incapacitation, internment, de-sexualization, and castration which modern societies reserve for the bodily other (incidentally, Böttner also died from AIDS-related complications). It’s also present in philosopher Paul B. Preciado’s iconic lecture on Böttner, Lorenza’s Way: Functional Diversity and Aesthetic Disobedience. In it, he reclaims the ground-breaking importance of her use of photography, performance, drawing, and painting as techniques to produce a dissident embodiment and political subjectivity. Blending Abstract Expressionism, figurative painting, and the feminist tradition of performance art, Böttner painted and danced, claiming the right to publicly exist and create in a transgender, armless body. Ultimately, this is what all the above performers, artists, and thinkers claim for all bodies and their need for care.

This notion of self-care, as in caring for the self, can’t be dissociated from collective struggles – from the recognition of oppressed, marginalised bodies: people of colour, women, queer people, disabled people. Rather than spending more time and money trying harder and harder to avoid burnout, which is a ‘shallow, haphazard, and contradictory’Jordan Kisner, ‘The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care’, The New Yorker, 14 March 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-politics-of-selfcare.approach to self-care, it would seem that a more appropriate way to care for ourselves would be to decolonise both the mind and the body and the art and the study. This would be an inherently radical form of action, on both personal and collective scales.

Editor's note. The third issue of Trigger, published in November 2021, gathers forms, coalitions, conflicts of (self-)care and archives of care through photography and visual art practices. While society faces a 'problem of care', artists and photographers 'document' ways to create more caring relationships between humans, technology, and nature. In the aftermatch of this printed publication, Trigger online continues to publish a diversity of independant contributions on the intricacies of care today. Lounguine's essay is one of those - giving a broad conceptual sweep to the concept of 'self-care' embodied in some of today's visual (sub)cultures.