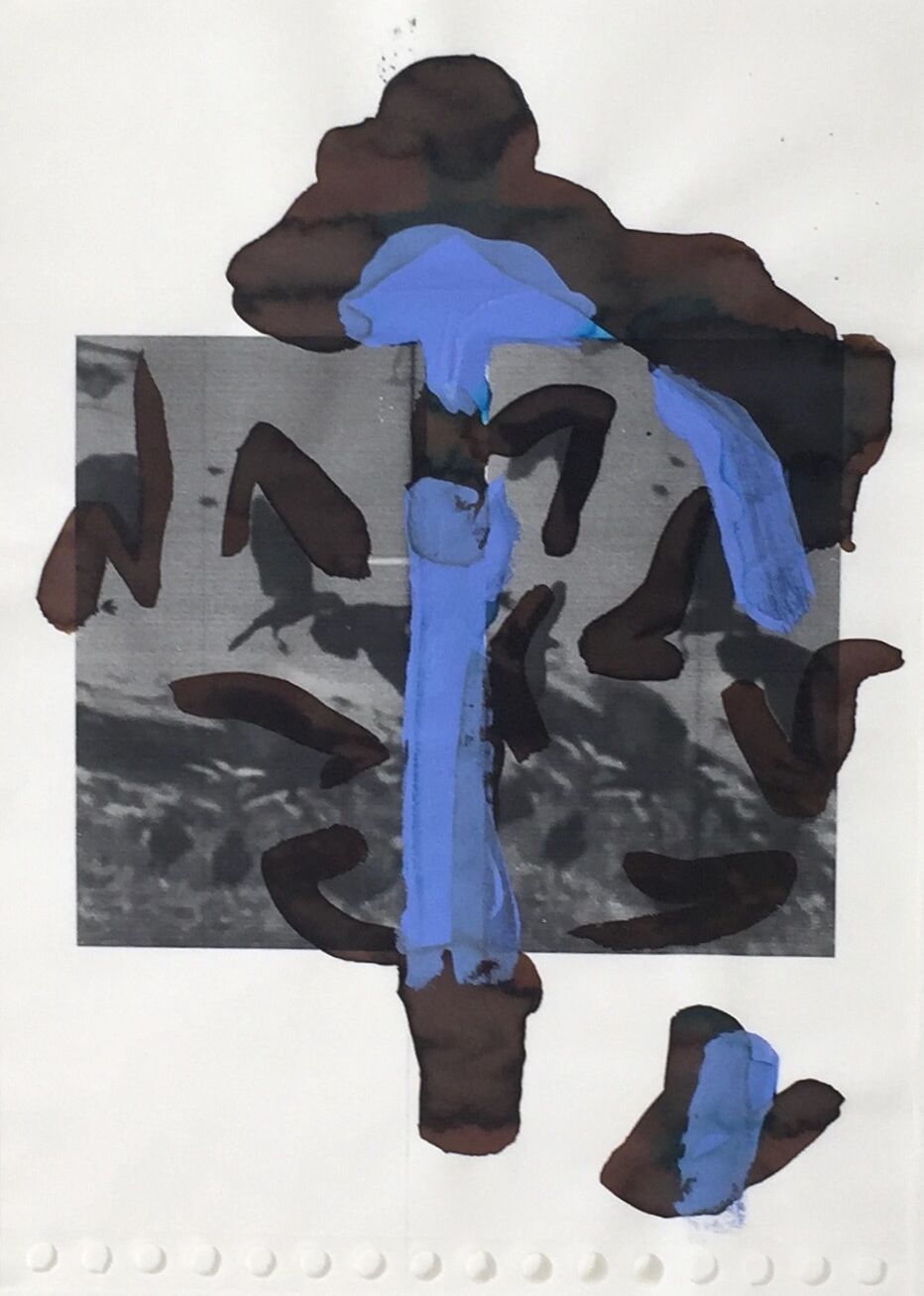

Sparks, 2020

Exile on the third floor. Isabelle Cordemans’ Cut-Ups Grief & Birds

Trigger launches a series of studio visits. How do artists and photographers work and make decisions before (even) thinking about exhibiting 'the work'? Art and photohistorian Inge Henneman is going back and forth between her place and an artist's work studio situated in Belgium. Through Henneman's fascinations and readings, these intimate visits of the studios she has selected, become different entries to understand and look at photographic practices in movement. Here's her studio visit n°1: Isabelle Cordemans.

‘Birds flying high

You know how I feel…’

– Nina Simone

‘We are like the birds. We adapt. We sing.’

– David Byrne

Inge Henneman

30 jan. 2022 • 10 min

I ring the doorbell of the Art Deco townhouse surrounded by old trees in the south of Antwerp, and she descends the staircase from the third floor to let me in. I have been visiting Isabelle Cordemans’ workplace for more than a year, watching a body of work grow slowly, feeling privileged to witness her creative process. As always, she offers me a cup of tea and invites me to stay for dinner. ‘Cooking is my default mode,’ she says, stirring the curry, checking the oven, improvising delicious dishes, with a finesse that flows seamlessly over into her deconstructive, image-based practice. Looking at her work is a synesthetic experience, as she wraps the spectator in spicy smells, soft lampshade lights, and music. She DJs her playlists to find the right atmosphere and mood. Counterpoint is core to her practice of putting disparate images together, watching to see which way the sparks fly.

Studio photo by Inge Henneman

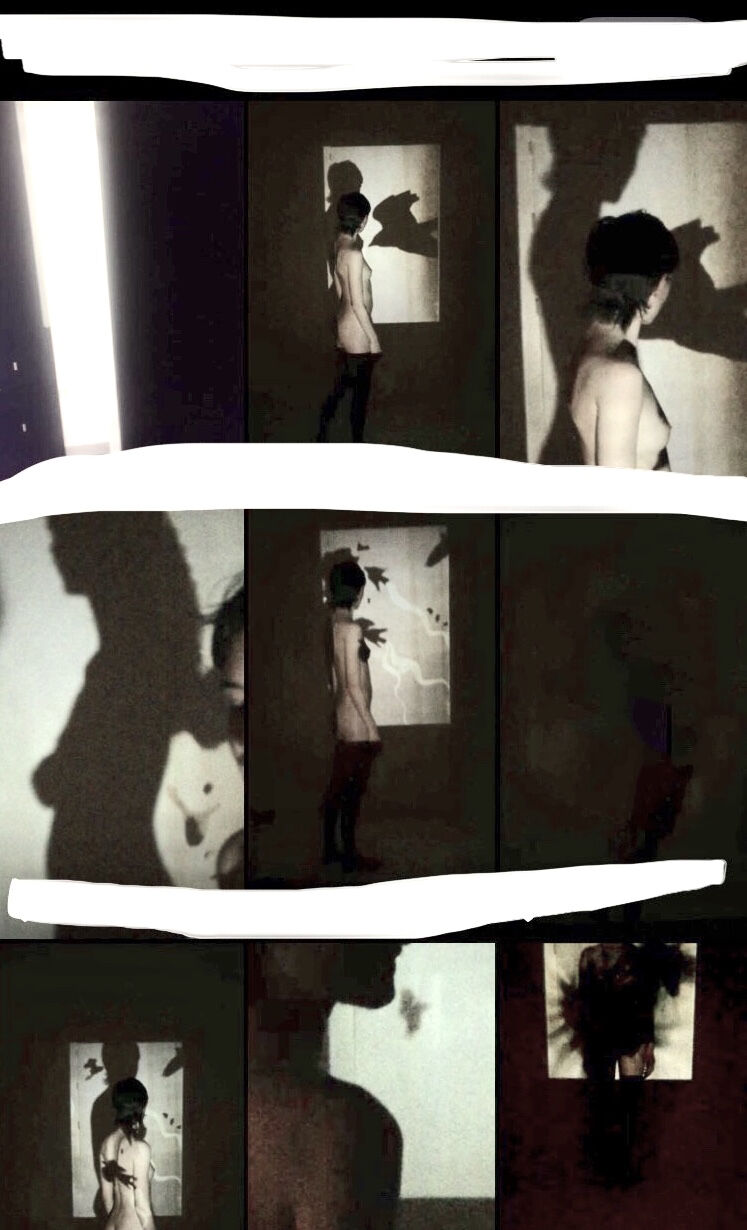

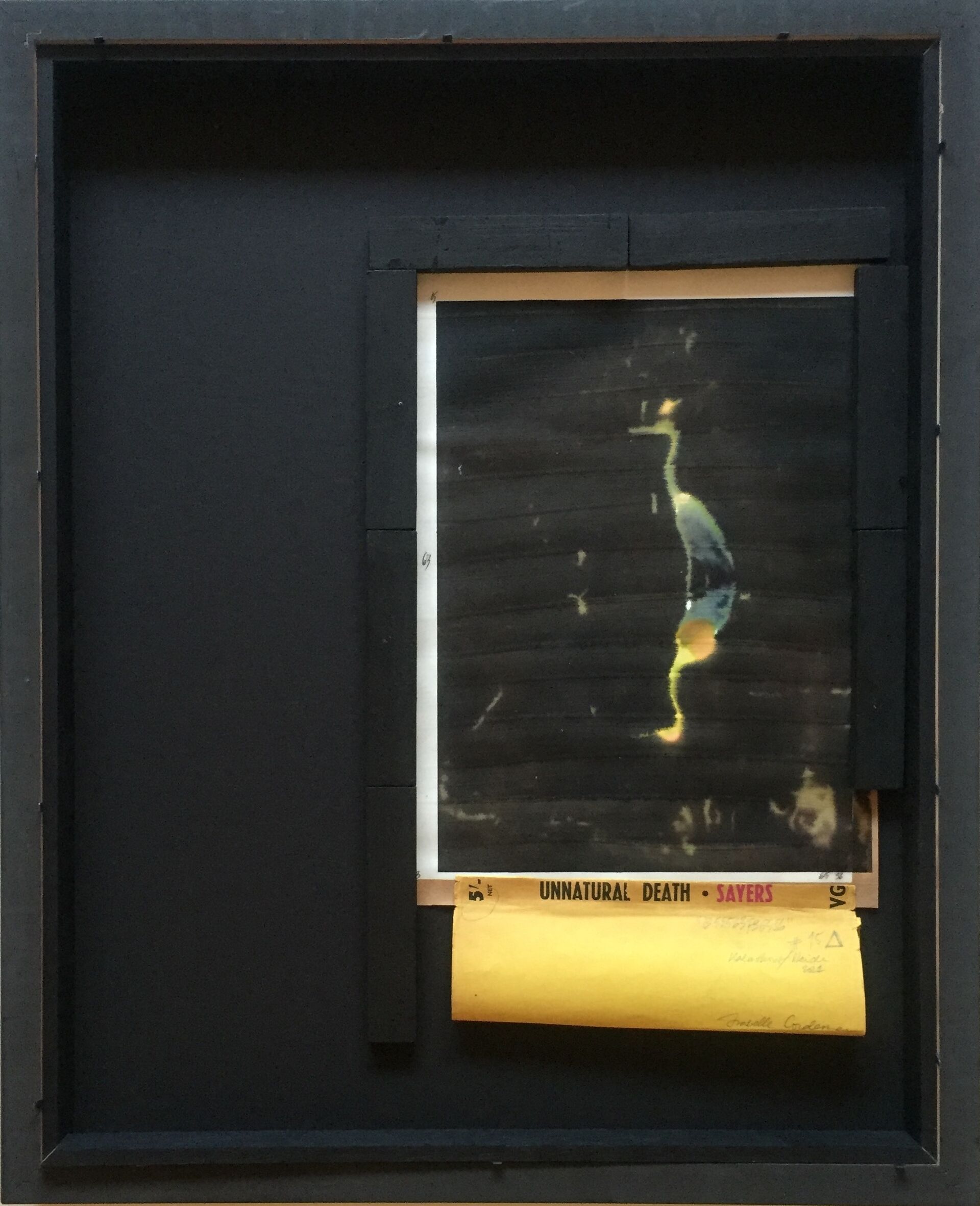

As she works in her living room as well as in the kitchen, there is no distinction between the artist’s studio and her home. In the messy muddle of everyday life, in between cooking, social activities, and the baseline stress of just surviving, collages and assemblages are made. I see piles of photographic prints and collages everywhere, loosely organized in folders of different sizes, scattered on large tables, on the wool carpet, on cozy sofas, and on shelves. Wooden frames hold prints and pictures in provisional arrangements – possible montages not yet fixed. Mounted on large paper strips hanging from the walls, prints are glued atop one another or aligned in horizontal sequences, like sentences to be read. Photographs are stuck on cardboard boxes and incorporated in sculptural bricolages standing crisscross on the windowsills and on the ground. At least three printers and a few computers give the living room the appearance of a laboratory, a frenzied print shop, or a domestic hotbed.

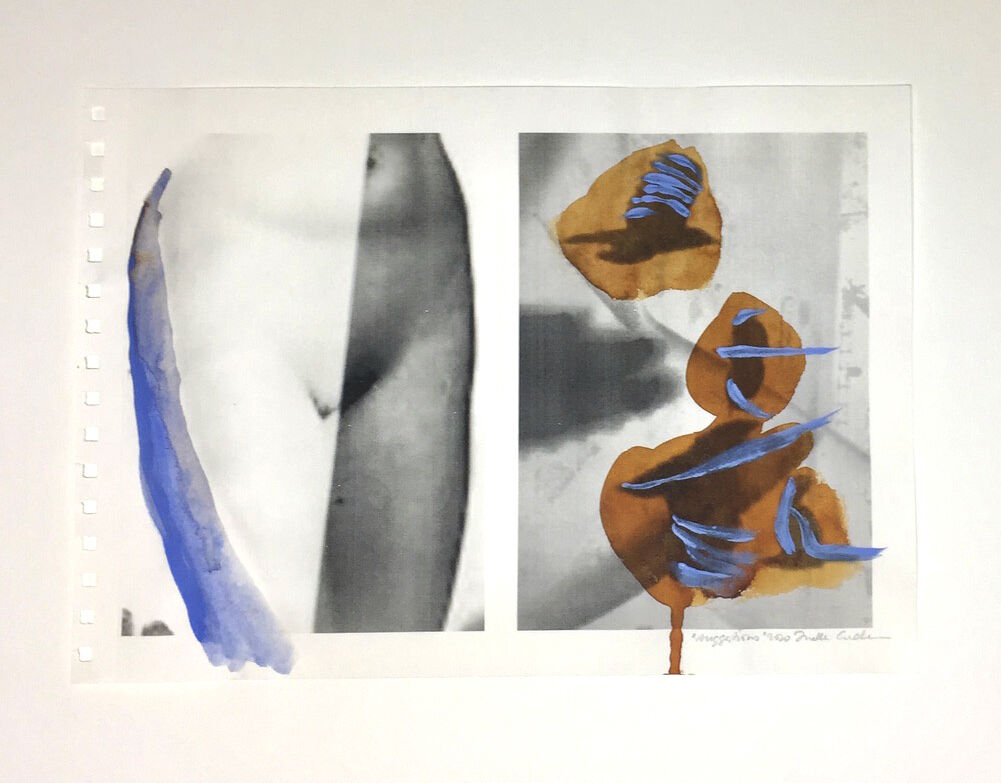

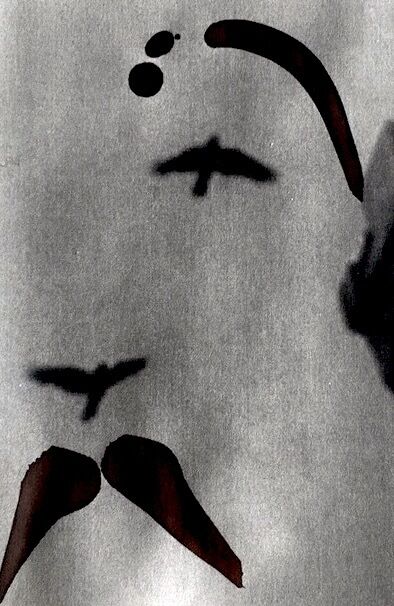

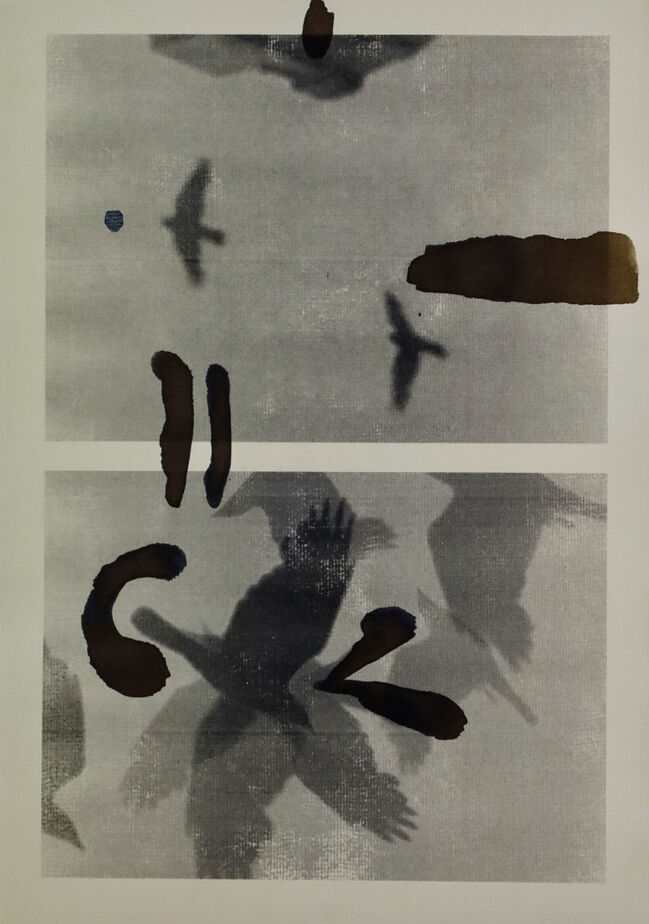

6, 2020

Everywhere the winged creatures announce themselves. The place is full of birds, birds, birds. Reduced to an abstract black silhouette, the motif of the bird is repeated in most of the visible compositions. Dark flocks flying against grey skies or landing in trees, grainy close-ups of crows and jackdaws create an emotional imaginary landscape of appearing and disappearing flying beings. The folders are titled: ‘Birds & Paint’, ‘Birds & Nudes’, ‘Black Birds’, ‘More Birds’, ‘Monochrome Birds’…

'Don’t explain', she says, 'move around it, like circling lines of thoughts. Walk with me. How does my work resonate with you?'

Since the death of her husband, Mark Babski, more than a year and a half ago, her insistence on the bird motif has become an obsession, a near identification, and perhaps a magical way of reconnecting to the missed loved one. The photographed birds are touched upon with a vividly coloured paint brush, caressed with sticky fingers, and scratched with graphite. Their fleeting presence as shadowy spirits suggests love lost and a message from the other side. She posts on Instagram, ‘Birds who dissolve, resolve, remind and rewind the winds and I can feel the warm air under their wings.’

A sudden gust of wind unsettles me whenever I see the birds appear in the prints. Like a glimpse of the soul leaving the body, the last twinkle of life fading from the eyes. Like falling in love but then in reverse. Sitting on the carpet amidst a multitude of collages, I respond to a feeling of tragedy and then, a feeling that counters gravity: a surprising lightness, a sense of play and levity.

This workspace envelops me like ‘a womb of things to be’ as well as ‘a tomb of things that were’, in the words of Ursula K. Le Guin.Ursula Le Guin, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, in Dancing at the Edge of the World (New York: Grove Press, 1989), 170.

These images matter. My response is more visceral than visual. The encounter with the work is more physical than optical, because it is more handmade than photographic, with the painted hues of blues and browns, ink sweeps and pink tape. The photographic print functions merely as the raw material for a continuous process of remixing and sampling, rephotographing and reprinting; for trying out different formats, qualities of papers, colours, and gradients. Cordemans turns photography against itself. Subverting its tendency to fix and freeze, creating a flow. Rejecting its flatness and placidity, looking for depth. Going against its cold surface, giving the image a skin. Undermining visual mastery, becoming haptic and tactile. In this compound of photography and plasticity, the readability of photographs is disrupted through optical confusion, technical experiments, manual interventions, and incessant reconfigurations through the act of reframing.

It’s easy to get lost in this chaos of non-monumental paper cutups. What and where is the work of art? Looking for cohesion, I get frustrated by the discontinuity and heterogeneity of the work on display. Every studio visit opens another visual field of constellations. The work is elusive and fluid, nothing is the same from one moment to the next and nothing ever repeats, although endless variations of the same accumulate.

‘Flocks at 7.56 p.m.’ Dinner is served amid collages and prints. Eight o’clock sharp the lovebirds fly by. On daily appointment, the ever-changing patterns of a flock in mid-air cause a sudden displacement of air and the sound of zooming. ‘Looking out from the windows of our third-floor apartment, I realized that the birds had been there with me all along, at the same level.’

What has kept me coming back to this work in progress is how it speaks of care and tenderness. As an artist-caregiver, restricted for years to a slow and isolated indoor life by the extreme demands of caring for a dying husband suffering from young-onset dementia – a situation exacerbated by the lockdown – Cordemans turned to the birds, observed and captured them with her iPhone, making photo collages at night on her mobile phone with a simple digital app. Opening her imagination to the birds and their other-than-human ways of living, she surrendered to a shift in perspective, becoming-with-the-birds, in a kind of parallel movement to her becoming-with-Mark – compensating for his failing vision, orientation, speech, and other declining faculties – in a type of acute experience of love, living in the proximity of death, close to the essence, in a domain bound neither by words nor by rational thinking.

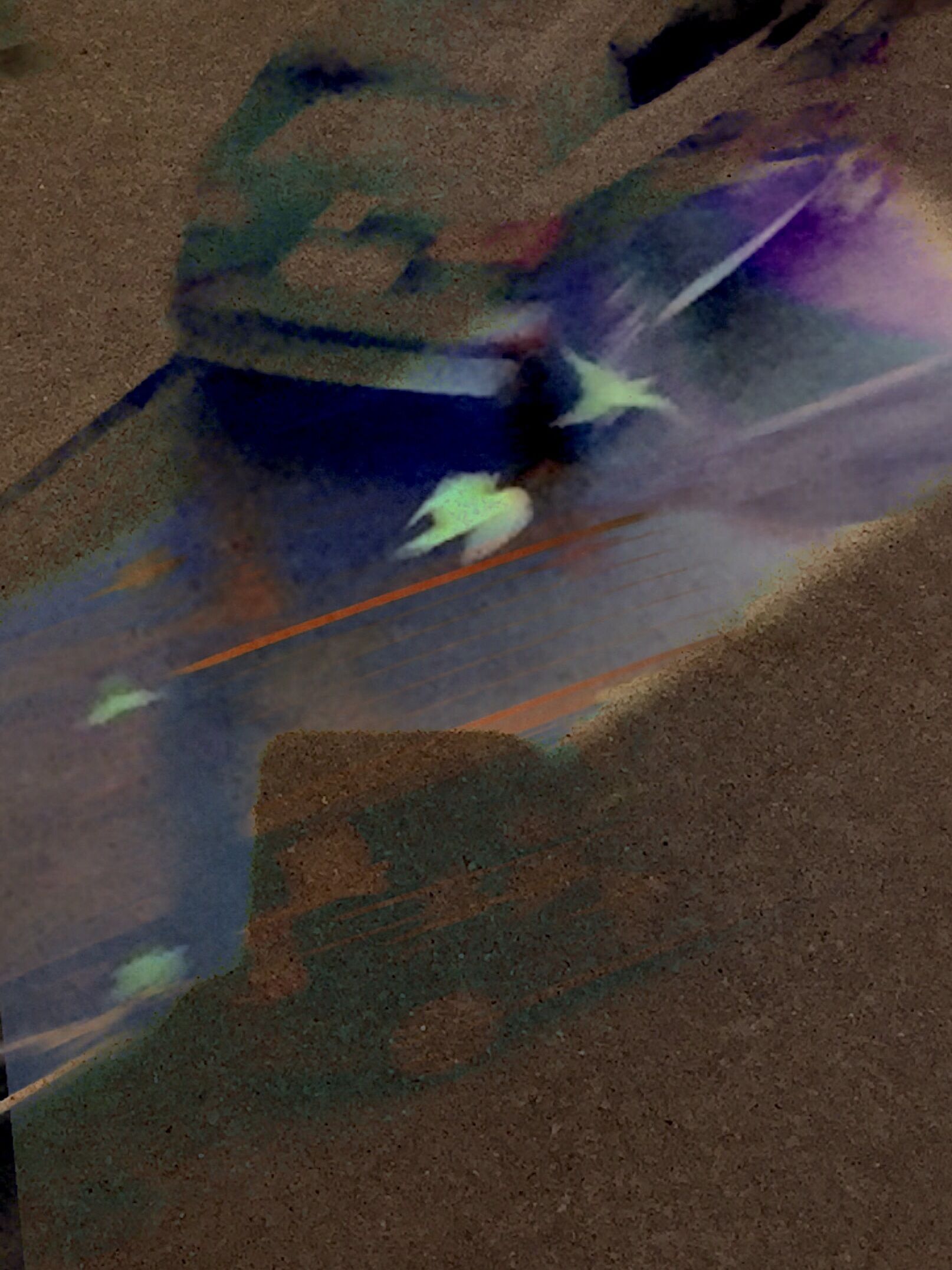

Nights, 2022

‘Every love story is a potential grief story’, says Julian Barnes in his novel Levels of Life. ‘You put together two people who have not been put together before … Sometimes it works, and something new is made, and the world is changed. Then, at some point, sooner or later, for this reason or that one, one of them is taken away. And what is taken away is greater than the sum of what was there. This may not be mathematically possible, but it is emotionally possible.’Julian Barnes, Levels of Life (London: Jonathan Cape, 2013), 67.

We’ve been talking for a year now, and every encounter changes my experience of the work, and every time again I lose my notes. Looking and thinking together, we pass back and forth the patterns we weave, proposing and inventing string figures as in a cat’s cradle game. I have become part of the creative process in a certain way, just as she becomes part of my writing. We are soul sisters in mourning a love lost. We are survivors in staying with the trouble. Inspired by a great documentary on Donna Haraway, Fabrizio Terranova’s Story Telling for Earthly Survival – a film we saw together at the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts – her book Staying with the Trouble became a common reference in our correspondence.Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin with the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016).

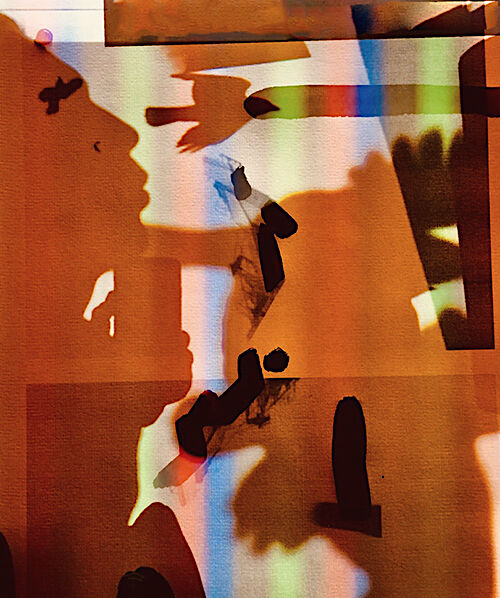

Waves of lights, 2022

But let’s return to my basic position in the studio: sitting on the floor with the ‘papiers collées’, trying to grasp what makes me come back again and again and what eludes and fascinates me in this work.

Everybody who has observed an artist in her studio knows that the artistic practice is the riskiest form of thinking in a space of creative uncertainty.Dirk Lauwaert, ‘Moi, j’aime les professeurs! (op een melodie van Offenbach)’, in De Witte Raaf 122 (2011), https://www.dewitteraaf.be/artikel/detail/nl/3091. While working, Cordemans intuitively and impatiently shifts, moves, stacks, masks, and unveils (parts of) pictures. She paints over and draws on the prints, she glues and layers, isolates and combines. How far can you go in the editing process? Taking a photo of a photo of a photo, misinterpreting and decontextualizing found images, finding impossible angles, she subverts their meaning. She inverses, reverses, distorts, and cleaves, flips sides and folds, mirrors and pins. In this ongoing process, she follows coincidence and welcomes happenstance. Commanding her devices without technical know-how, she experiments with the instrumentarium of computers and printers like a jazz musician playing her battery without knowing how to read notes. Giving up control, she sabotages and manually intervenes in the mechanical program of her apparatus.

Working with cheap phones, shooting blind, at random, the original camera-capture of the birds in motion from her balcony on the third floor, is but a small and ‘poor’ image, reduced in the chain of exorcist manipulations to an abstract trace, a sheer ‘presence’ of energy. Her strategy is to ask ‘What if?’, to destroy the literal, to unhook and to edit to death.

In this way, the birds are set free.

Not everything is centered and not every heron is grey white or blue only, 2021

Again and again, a given image is juxtaposed with a strange element. Attacking the self-contained autonomy of the image, the artist seems to aim at a perpetual perceptual shifting, creating totally different mutations of the same thing. In this way she accepts and performs in her work what Haraway calls ‘the risk of radical contingency, of putting relations at risk with other relations, from unexpected worlds.’ Montage is not putting a priori units together, because ‘when it works, something new is made and the world is changed.’ In the unique relation of the chance encounter, something is created that is ‘greater than the sum of what was there.’ Nothing can be seen in itself. Nothing is ever just one thing.

Again and again, the fixed is destabilized in the mutable by an inspirational gesture, a sudden gust of wind. In this way, Cordemans unlocks the potential for surprising change. Can we see new possibilities in any given moment? Can we trust our experience? Can we think through precarity, as Anna Tsing asks us to do?

‘Precarity is the condition of being vulnerable to others. Unpredictable encounters transform us; we are not in control, even of ourselves…. [W]e are thrown into shifting assemblages, which remake us as well as our others.... Indeterminacy, the unplanned nature of time, is frightening, but thinking through precarity makes it evident that indeterminacy also makes life possible.’Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015), 20.

I discovered in the studio of Isabelle Cordemans that every artistic practice is one of making as well as thinking. I discovered how loss can function as a creative principle that engenders openness. What if her attitude of mourning not only sets the birds free, but liberates us as well, from our fixed perceptions and mental frames?

The only thing we can do when love is lost and nothing works is to stay with the trouble, to get ourselves out of the way and lose control. What if surrendering to chance is the same as learning to love? What if a momentary loss of control, a sudden gust of wind, is the essence of the creative act?

Inspirational sources: Donna J. Haraway, Julian Barnes, Joan Didion, Tim Ingold, Dirk Lauwaert, Tina M. Campt, Anna Tsing, Vinciane Despret.

Thank you, Isabelle Cordemans.