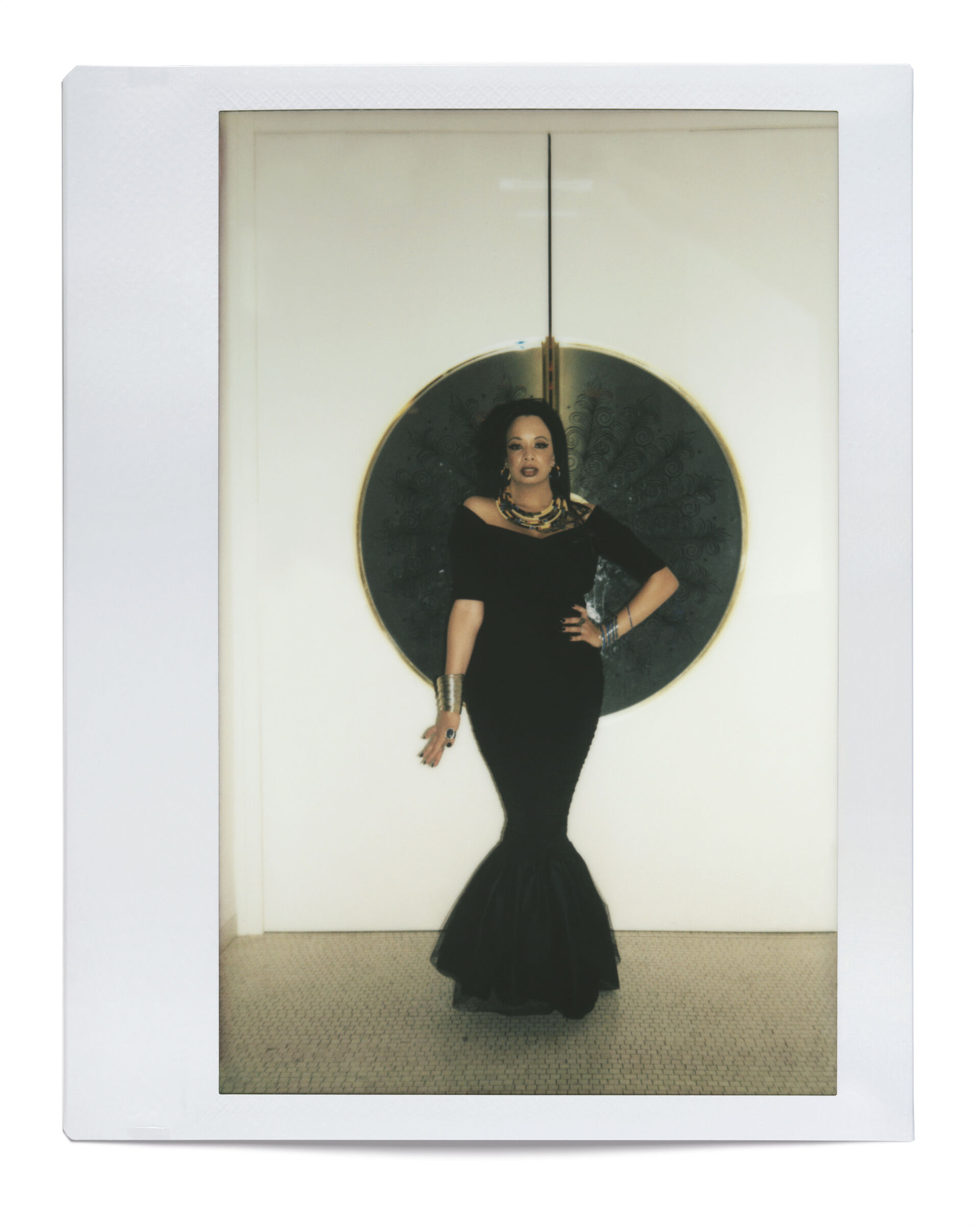

The author photographed by Gabriella Falana

Erotic of Scholarship: On the place where birds can sing again

Editor's note: This contribution can be viewed together with Julia Gaes' insights into the ways her artistic collaborative practice on the burlesque evolved: 'Returning to Wigs & Gloves: Recounting my artistic interest in burlesque and drag'.

Joanna Staskiewicz

26 nov. 2024 • 21 min

Jacques Derrida once had the wonderful idea of an unconditional university. This university wouldn’t be just an ivory tower or a production site for future elites but a place of exchange, discussion, and an inclusive language. As he put it, such a university ‘should remain an ultimate place of critical resistance – and more than critical – to all the powers of dogmatic and unjust appropriation’,Derrida, 204. and thus it wouldn’t be bound to an institution or educational establishment; it could be anywhere such critical and liberating energy might unfold. When I was doing my research, the best universities were bars – not only burlesque bars but any bar with locals, where I could meet the most impressive people from different backgrounds and with different life stories, sometimes with broken biographies.

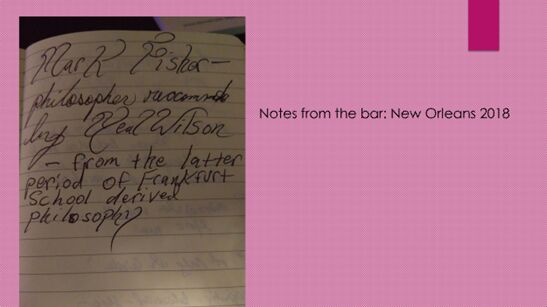

In New Orleans, for example, I remember talking with a brilliant young man from rural Louisiana, who had started his studies of philosophy as the first person in his family to go to university, but he didn’t finish his degree because he felt alienated at the university, and that he didn’t belong in academia. In my research notebook, he wrote the names of his favourite philosophers and writers, and these notes remind me that we can find so much surprising knowledge in spontaneous and random encounters.I met this brilliant man again in September 2024 at the same bar during my current stay in New Orleans as Fulbright scholar. He told me that he’s just finishing his science fiction book.

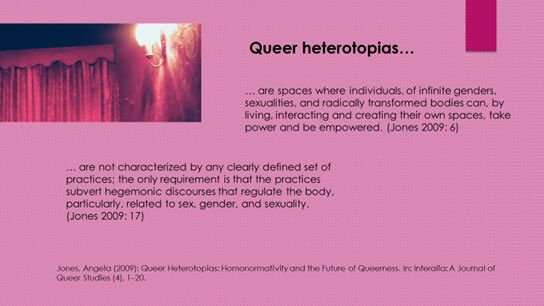

Burlesque bars, like Zum Starken August in Berlin or Madame Q in Warsaw or The Always Lounge in New Orleans, are also a kind of an unconditional university, a queer glitter heterotopia, to borrow a phrase from Angela Jones – places of withdrawal from the restrictions and humiliations and everyday wounds of hegemonic discourses, places of empowerment.Angela Jones, ‘Queer Heterotopias: Homonormativity and the Future of Queerness’, Interalia: A Journal of Queer Studies 4, no. 4 (2009): 1–20. During my research, I could feel exactly such a queer heterotopia in burlesque venues, because all these places have something in common: they are places of safety, solidarity, and humour. In these glitter heterotopias, I could make use of my academic approach, which I call the erotic of scholarship, and which I would like to introduce now.

Here, first, I’d like to thank professor and comedian Jane Banks from New Orleans, who brought to my attention an approach to academic study called autoethnography, which means to connect our biographies, and even our feelings and emotions, with our research. This method is also related to Lauren Fournier’s concept of autotheoryLauren Fournier, Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism (MIT Press, 2021). and Donna Haraway’s concept of situated knowledge.Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599. Autotheory is a feminist practice that rejects the possibility of objective research. I share this methodological approach, which, in addition to research, incorporates everyday encounters, exhibition visits, and conversations – not only academic ones but also interviews in clubs and bars, which can influence the direction of the research in surprising ways.Fournier, 5. The experiences imprinted in one’s memory during this research should also be included in the analysis.Fournier, 14–36.

The concept of autoethnography focuses more on the relational aspect of the people or scenes included in the research. One form of autoethnography is ‘narrative ethnography’ – texts written in narrative form that contain the experiences of the scholar.Carolyn Ellis and Arthur P. Bochner, ‘Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject’, in Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 733–768. In my case, these include my own drawings of performances that I’ve seen. It’s then my own interpretation of the performances, which I also include in my book, that should be considered an academic qualification. I take this risk!

Another form of autoethnography is ‘reflexive ethnography’, which holds that research has its starting point in biography and considers how scholars change through their studies.Ellis and Bochner., 740. I can definitely say that my research on burlesque has changed me and transformed me in the creation of an academic burlesque, which has had a carnivalesque liberating effect and has become a very passionate journey for me. And passions, as well as emotions, are sometimes regarded as something non-academic, unfortunately. In her classic text on the situatedness of knowledge, Haraway notes that it’s necessary to incorporate a ‘passionate detachment’Haraway, 585. into the production of knowledge. This concept brings sensuality and physicality to thinking and research. Thinking and theories should not be cold, lifeless, abstract, pseudo-objective concepts of thought but rather should have a relationship to both the research topic and the scholar themself. I’m therefore arguing here for bodily, corporeal research. To use Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s words, we should bring more of the ‘carnal’ into theory.Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, ed. Claude Lefort, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Northwestern University Press, 1968). The perceiving and feeling body – in this sense understood as Leib – with which we perceive the world; with which we experience the sensual, from joy to pain; with which we can rebel but also stumble; with which we perceive and feel others – the flesh of the body allows us to understand the flesh of the world. The body is our medium for understanding the world and others.Merleau-Ponty, 248–249.

The exploration of burlesque is like a ‘being a presence to the world through the body and to the body through the world, being flesh’.Merleau-Ponty, 239. It is the joy of exploring the sensual, physical, and humorous in the phenomenon of (neo-)burlesque. It’s a kind of sensual experience, not only during the act of performance and its production but also in its reception.

It’s an eroticism that calls to mind Audre Lorde’s famous plea for more erotic value in our everyday life, for erotic power and life appeal and fulfilment in our work.Audre Lorde, ‘Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power’, in Writing on the Body: Female Embodiment and feminist theory, eds. Katie Conboy, Nadia Medina, and Sarah Stanbury (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 277–282. I understand this as passionate research, as an erotic of scholarship. And as I mentioned before in relation to autoethnography, our research has its starting point in our biography.

During the interviews with performers, I was asked how I came to focus my research on burlesque, and I’m going to tell you my story here. In one of my childhood pictures from the early 1980s in Poland, I’m pictured in the middle of my my siblings and cousins, all of us about the same age and sitting on a big armchair, me the youngest, maybe three years old, in the middle, squashed between the legs of the other children with my tights hanging down. When I look at this picture today, I remember that very often I felt constricted by society, like I was in that chair by my family members. But I always felt great in a circus cabaret–like universe, like those in the films of Federico Fellini, and was impressed by the world of outsiders, of clowns, of people looking for magic, like Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, of the world of divas like Lola Lola, played by Marlene Dietrich, who degraded professor Unrat to a clown in The Blue Angel, or capricious Sally in Cabaret. During this time, I lived with my parents in an old manor house, which functioned as a socialist institution for women with ‘psychiatric disorders’ in a post-German village in western Poland – a somewhat unusual environment for a child, but my parents worked in this institution.

In the ‘asylum’, which Michel Foucault so impressively described as a ‘heterotopia of deviation’,Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces’, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 22–27. the patients created a protected space that seemed more trustworthy than the world outside this heterotopia. The villagers outside the asylum seemed, to use Foucault’s description, like those who associate with ‘sovereign reason’Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, trans. Richard Howard (Routledge, 2005 [Librairie Plon, 1961]), xi – like those who are ‘normal’. For me, the category, what was normal or not was already blurred; the women, patients of this asylum, were my friends. They were ‘normal’, and the village people outside, in the conservative, Catholic village, were bizarre to me as a child.

Later, when I read Unica Zürn’s brilliant The Man of Jasmine, I came across a passage in which Zürn describes having to deal with people who were labelled as ‘insane’ as a child, who she closed in the heart while non-'insane'-others made her feel uncomfortable.Unica Zürn, The Man of Jasmine (London: Atlas, 1994). She saw the world of the ‘insane’ people as more beautiful, and this passage really spoke to me.

But what does growing up in an institution have to do with burlesque? The link between an institution for the ‘mentally ill’ and burlesque must, of course, be carefully considered and justified so as not to give the impression of relativising the state surveillance apparatus and the history of psychiatry, or of placing the performance art of burlesque in the strange corner of ‘mental problems’. I became aware of the connection between burlesque and my having grown up in a psychiatric clinic when I first read Foucault, because he impressively showed how social standardisation processes take place and how those who don’t conform to the ‘norm’ are socially excluded. And exactly that’s what was said about burlesque art in its beginnings. When Lydia Thompson, considered to be the first burlesque performer, and the British Blondes toured the US in the 1860s and shocked the upper classes with shorts and legs in body-coloured tights, confidently returning the public’s gaze, playfully acting male roles through cross-dressing, they aroused both horror and curiosity. Burlesque was considered, as Peter Stallybrass and Allon White put it, as ‘low other’.Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression, (London: Methuen, 1986), 5–6. As something that arouses disgust but also longing and desire that undercuts ordinary bourgeois values, the burlesque was and still is a fascinating abject.

Later, I read Foucault, Derrida, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, and Susan Sontag with great passion, because their theories of deconstruction helped me to deconstruct things that made me feel imprisoned or constricted. One of these things was Polish Catholicism, which I deconstructed with my PhD dissertation on the Catholic church in Poland. But it was during my PhD that I had my first visiting researcher stay in New Orleans and discovered burlesque for myself, and it was like meeting again with all my beloved figures from my childhood. The first burlesque I saw was the nerdlesque show produced by Xena Zeit-Geist and the Society of Sin. It was in December 2015, and the burlesque play was titled A Pulp Science Fiction: A Star Wars Burlesque Play. The performers represented different body types and genders. Zeit-Geist, the show’s producer, performed Darth Vader while the others embodied aliens, animal-like beings, and futuristic figures. The diverse performers didn’t necessarily fit into the gender binary, and the play culminated in a game with temporal and spatial dimensions.Joanna Staśkiewicz, ‘The Queering Relief of the Humor in the New Burlesque’, Whatever. A Transdisciplinary Journal of Queer Theories and Studies 4, no. 1 (2021): 187–218. The mix of futuristic–intergalactic Star Wars cult and earthly Pulp Fiction cult from the late twentieth century created a protecting space of transgression, an utopian place as described by Foucault, where one could be a body without a body and escape the prison of one’s own corporeality: ‘Utopia is a place outside all places, but it is a place where I will have body without body, a body that will be beautiful, limpid, transparent, luminous, speedy, colossal in its power, infinite in its duration. Untethered, invisible, protected – always transfigured.’Michel Foucault, ‘Utopian Body’, in Sensorium: Embodied Experience, Technology and Contemporary Art, eds. Caroline A. Jones und Bill Arning. 229–234 (MIT Press, 2006), 229.

That was the moment I found my new research topic, or rather found it again, because the topic had been in me for a long time. I started reading academic literature about burlesque, and my first book was Happy Stripper by Jacki Willson.Jacki Willson, Happy Stripper: Pleasures and Politics of the New Burlesque (I.B. Tauris, 2008). This brilliant book was one of the first academic books on burlesque, and I loved the connections Willson made with feminism, art, and activism, as well as her autoethnographic writing. Just as enchanting was Willson’s second book, Being Gorgeous: Feminism, Sexuality and the Pleasures of the Visual, which is a brilliant plea for sensual costuming and playful masquerade to allow people to transform themselves from ‘being sex objects to self-determined art objects’.Jacki Willson, Being Gorgeous. Feminism, Sexuality and the Pleasures of the Visual (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015): 7. Jacki’s the text on feminist ‘piss-takes’ and the impact of humour as feminist strategy was also very inspiring for me,Jacki Willson, ‘“Piss-Takes”, Tongue-in-Cheek Humor and Contemporary Feminist Performance Art: Ursula Martinez, Oriana Fox and Sarah Maple’, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal 36 (2015): 5–12. and I knew after reading these academic texts that I would also like to go in the burlesque direction as a scholar.

And then I visited Warsaw in 2018 for my first reconnaissance in burlesque, and I discovered a special queer glitter heterotopia called Madame Q, founded by Betty Q, Madame Méduse, and Pani Misia. This place, which is a kind of alternative theatre with cosy vintage furniture and a campy look, allowed me to escape from the conservative backlash outside during the third year of the right-wing conservative Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość; PiS) party rule in Poland. During this time, I could attend several burlesque shows at Madame Q with a clear political message, where performers addressed the audience directly. At that time, demonstrations against the ban on abortion were taking place across the country, and I could see shows by Betty Q and Lola Noir, in which they integrated the struggle for reproductive rights into the story of their performances. During my last research visit in March 2024, I saw that the political impact of the burlesque shows at Madame Q has not diminished, and I found more acts expressing topics of queer activism, like the legendary pride act of Madame Méduse, a strong manifesto of queer pleasure and against the homophobia in the still Catholic-dominated Polish society.

When I saw burlesque in Warsaw back then in 2018 and also started to attend burlesque shows in Berlin, I was wondering about the situatedness of burlesque, how burlesque uses local codes, myths, and legends. In a show in Poland, for example, a performer cited Adam Mickiewicz, sometimes referred to as the Polish Goethe, in his performance, turning his burlesque performance into a literary one – a move that would be difficult to understand without knowing the literary codes that almost everyone in Poland learns in school. In New Orleans, likewise, many performers use the myth of a city of ghosts, Southern Babylon, vampires, and voodoo; performances also deal with the dark history of New Orleans as infamous metropolis of slavery. The Berlin burlesque scene continues to be the biggest challenge for me, not only because of its size and the internationality of the performers but also because of the breadth of its themes. Various burlesque venues and themes include queer activism, dark cabaret, the myth of Berlin as Babylon, including references to the Golden Twenties, sideshows, circuses and freakshows, motifs and the myth of the city of electro music, which is reflected in a strong connection between the burlesque scene and the club scene.

During my exploration of burlesque, I soon realized that these performances are much more than seduction, wigs, gloves, high heels, and feathers. They often incorporate the very personal stories of performers, which vary as expressions of vulnerability, queer desire, depression, marriage, love, obsession, drug addiction, and the deconstruction of oppressive religious or political restrictions. This made me think of burlesque as a kind of theatre of cruelty, in the words of Antonin Artaud – relief through performance, not only for the performers but for the audience as well.

In his book The Theatre and Its Double, Artaud calls for emotional disorder on stage: for him, theatre should not only be beautiful or entertaining but also emotionally exhausting, cruel, and even painful. As he writes, ‘An actor is like a physical athlete, with this astonishing corollary; his affective organism is similar to the athlete’s, being parallel to it like a double, although they do not act on the same level. The actor is a heart athlete’, who takes the audience out of their comfort zone with a physical performance that is more visual than textual.Antonin Artaud, The Theater and Its Double (London: Calder Publications, 2001 [Gallimard, 1938]), 88.

In the same way, contemporary burlesque embodies an emotional upheaval. I see this theatre of cruelty as a queer strategy, or more precisely, as a strategy of queering one’s own biography, because burlesque performers tell the story through the mirror of their own biography – with their own bodies.Joanna Staśkiewicz, ‘Killing the Pain with Pleasure: On the Queering Effect of the Neo-Burlesque’, in Queer Pop: Aesthetic Interventions in Contemporary Culture, eds. Bettina Papenburg and Kathrin Dreckmann (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2024), 119–135. This strategy is reminiscent of Elizabeth Freeman’s concept of erotohistoriography, which is a way of escaping the confines of everyday life and the trauma of everyday wounds. According to Freeman,

‘As a mode of reparative criticism, then, erotohistoriography indexes how queer relations complexly exceed the present. It insists that various queer social practices, especially those involving enjoyable bodily sensations, produce form(s) of time consciousness, even historical consciousness, that can intervene upon the material damage done in the name of development. Against pain and loss, erotohistoriography posits the value of surprise, of pleasurable interruptions and momentary fulfillments from elsewhere, other times.’Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. ( Duke University Press, 2010), 59.

Such an erotohistoriography is very much in demand, especially in a time of a political shift to the right, and perhaps that explains the popularity and vitality of contemporary burlesque shows, as queer burlesque venues are places that are full of pleasure.

The situatedness of the burlesque, which queers not only gender and desire but also the local myths and biographies of performers, is connected to the situatedness of research, which is part of my concept of the erotic of scholarship. Ironically, I see the erotic in burlesque not only in sexual seduction but also in the personal stories told by performers with their bodies, in their vulnerability, and in their empowerment through this as well. For me, erotic means attending to these acts of self-expression and being part of this contagious act of empowerment. I’ve already mentioned Lorde’s concept of the erotic as pleasure and satisfaction drawn from the things we’re working on. The erotic in Lorde’s sense becomes apparent to me when I see the cathartic impact of burlesque, which works like pleasurable relief from everyday wounds not only for the performers but for the audience as well. It’s the erotic of emotional expression and of showing oneself in one’s vulnerability, which is so powerful. The erotic of scholarship means something similar: to bring body and soul into research, to bring emotions and one’s own vulnerability to it, to lose fear of failure, of not being taken seriously.

The effect of burlesque is comparable to what Jack Halberstam said about the ‘silly archives’ – that a banal pop-cultural text can say more about social structures than a serious academic one.Judith Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure ( Duke University Press, 2011), 60. Burlesque can be an outlet for emotions such as anger and rage, and for the deconstruction of Catholic education or patriotic myths, and it has a political effect. It’s also the effect that Artaud called for in his theatre, a kind of bewitchment, stupefaction, and liberation, where simple gestures have a profound intellectual effect. If burlesque is a temporary resistance to the rules of everyday life, then it’s not only a form of performance art but also a community.

The effect of burlesque is also found in its most characteristic element: glitter. As Nicole Seymour notes, glitter is associated with queerness, not only in the aesthetic sense, as an inherent body prop, but also in a metaphorical sense, as an embodiment of community and queer activism: ‘No one bit of glitter is glitter; no one bit of glitter glitters. And this is true on the most basic of etymological levels: as a collective noun, “glitter” has multiplicity built into it.’Nicole Seymour, Glitter (Bloomsbury Academic, 2022), 38. Thus glitter is never just one glitter – there’s always a connection. Glitter is always plural; it is community. Glitter is also subversive, not easy to remove. And this is the way I see the burlesque community, which has a very huge impact and enormous potential to subvert norms.

According to Angela Jones, ‘Queerness is a refusal: it is a dismissal of binaries, categorical, and essentialist modalities of thought and living. Queerness is always being made, remade, being done, being redone, and being undone. It is a quotidian refusal to play by the rules, if those rules stifle the spirit of queers who, like caged birds, cannot sing.’Angela Jones, ‘Introduction: Queer Utopias, Queer Futurity, and Potentiality in Quotidian Practice’, in A Critical Inquiry into Queer Utopias, ed. Angela Jones ( Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 14. As I noted above, burlesque is much more than feathers and corsets, or simply eroticism and tease. It’s a place where the birds can sing again.

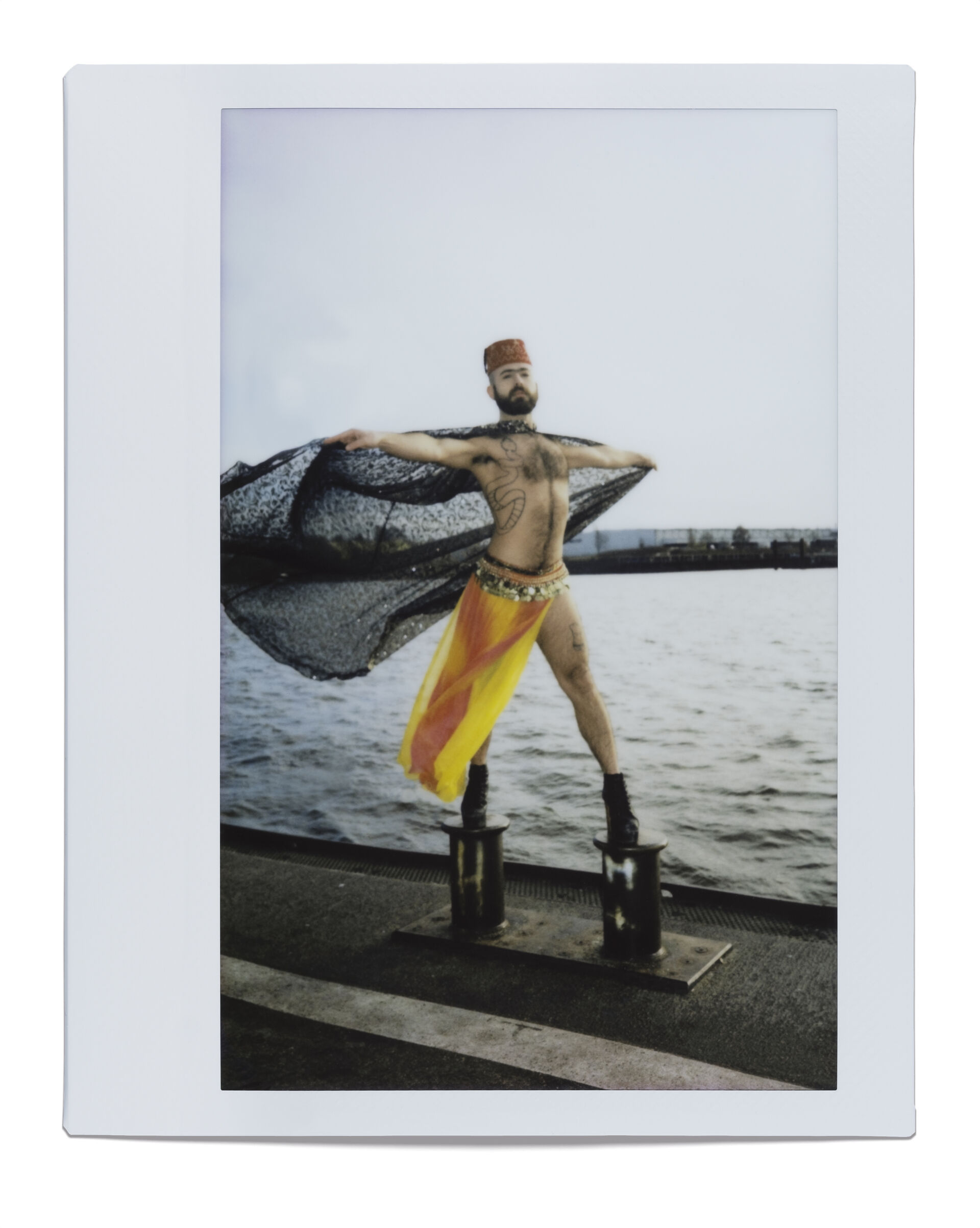

Wigs & Gloves - Theodora Rex, Julia Gaes 2019-2022.

This ‘more’ is also what is visible in Julia Gaes’s photographs of burlesque and drag performers. These are not just burlesque poses, costumes, or props. Gaes arranges a photographic scenery that both emphasises the situatedness of burlesque and depicts an autotheoretical or autoethnographic moment in photography. In Camera Lucida, Barthes argues that a photograph shows a person frozen into a mask – a face that reflects the social order, because the face in the photograph is a ‘product of a society and of its history’.Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 34. Gaes’s photographs seem like these autoethnographic portraits, even self-portraits in the sense of self-revelation: the disguising mask of the burlesque costume in a new setting, which is taken from the safe space of a burlesque drag bar, reveals the performers in all the vulnerability and agency that comes from being offstage. Richard Weihe describes the paradox of the mask as a dialectic of showing and concealing:Richard Weihe, Die Paradoxie der Maske: Geschichte einer Form (Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2004). referring to Sigmund Freud’s distinction between the unconscious and the conscious, he sees the mask as the surface – the consciously controlled, socialized ego that covers the face, i.e., the unconscious, repressed, and instinctive. The burlesque poses and gestures look different in Gaes’s photographs against new backdrops. The wide expanse of the port of Hamburg, for example, transforms the pose of the burlesque performer Eve Champagne, with her arms folded, into a defiant sailor and an angelic pin-up model, but the eroticism and seduction is not revealed in the poses; it is in this connection with her surroundings, with the sensuality of the world.

Walter Benjamin once said, totally fascinated by the circus world, that for him all peace negotiations should be conducted in the circus, because the circus is a place of both self-irony and amusement.Walter Benjamin, Kritiken und Rezensionen (Suhrkamp, 2011), 71–72. Drawing on this idea, I’d add that today, in these times of such unrest, perhaps there are burlesque venues where peace treaties should be negotiated. These glittering queer places enable a temporary suspension of everyday life, allowing a brief distance and a space in which the birds can freely sing their own song again. My plea for more self-irony, for pleasurable research through autoethnography, for not being afraid to bring emotion into research, for not being afraid of not being taken seriously – these are the basic features of the erotic of scholarship. Because, speaking again through Halberstam, ‘Being taken seriously means missing out on the chance to be frivolous, promiscuous, and irrelevant. The desire to be taken seriously is precisely what compels people to follow the tried and true paths of knowledge production around which I would like to map a few detours.’Halberstam, 6.