At my home in Rotterdam, I have a view overlooking the Maas River. There, I can see the relentless march of ships and barges steadily ploughing the currents, making their way to and from one of the busiest and most important ports currently enforcing the circuits of global capital. These ships carry neatly stacked rows of metal shipping containers stuffed in their bellies and on their backs. The boxes are standardised to be stuffed and unstuffed, stamped with recognisable names like Evergreen, Matson, Maersk, Hyundai and Yang Ming. Within these containers, lumbering around the world from port to port to port, is the ‘stuff’ that drives our global economy, clothing us, feeding us and enriching us.

While this depiction of globalisation might generally seem to be one of smooth and effortless consumption, what’s often left aside – or expelled – are the conditions of marginalised labour forces, environmental limits and other questions of precarity and exploitation. My work as a photographer is situated in these crevasses and forgotten spaces; that is, I look to the material conditions of globalisation and try to show how the free flow of commodities – the circulation of capital – actually consists of violent and contested human relations. This is nothing new. American critic, writer and photographer Allan Sekula’s photography and text publication Fish Story is one such influential project that sought to convey the complexity and precarity of human geographies within capital’s global flows. Fish Story simply reminds us that the world’s goods are mostly shipped across seas and that, in fact, as Herman Melville already pointed out in Moby Dick, the Pacific is a sweatshop.Pascal Beausse, ‘The Critical Realism of Allan Sekula’, Art Press, no. 240 (1998): 25.

What unites Sekula’s Fish Story and my own photography is the question: what makes things circulate? This circulation of goods, people and commodities is what geographer Deborah Cowen called the ‘logistics planet’, an entanglement of infrastructure and logistics that govern global flows in a geography of production, distribution and consumption.Deborah Cowen, The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade. (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 2. Ultimately, what I want to know is how the generally accepted picture of globalisation can be ruptured and challenged. Can photography contribute to a counter-picture of globalisation? Fish Story has provided a unique vantage point for helping me create possible methods to rupture this view. Sekula’s critical and artistic project centres on the corporeal, and is steeped in the violence and disorder of the maritime economy of capital exchange. He called this crude, or stubborn, materialism.Allan Sekula, Fish Story, (3rd New ed; London: Mack, 2018), 12. I prefer to call it a ‘dirty picture’: a photographic methodology that insists on the physical and material as fundamental agents that shape our behaviour and social structures. It’s for these reasons that I turn to Fish Story to use as a case study in this essay and which I also connect to my own practice. It’s my aim as a photographer to manifest an image of globalisation that’s visible, tactile and potent – that is, dirty. Here’s a small survey of what you’ll find in Fish Story: pictures of a scavenger named Pancake in a disused shipyard in Los Angeles; a golf course reserved for visiting ship owners at a Hyundai shipyard in South Korea; a monument to the defenders of Veracruz, Mexico; the ocean terminal of Victoria Harbour, Hong Kong; unemployed Polish shipworkers; a sailor phoning his wife from the Port of Rotterdam. I call these photographs ‘dirty pictures’.

These dirty pictures present to me, as a photographer, an aesthetic struggle, yet also a way forward. Sekula understood this dilemma. His photos ensure that human labour will always emerge from the shadows of containerisation, not forgotten and erased, exploited as a transnational instrument for globalisation. Sekula asserted that for a photographic practice to challenge the picture of contemporary capitalism as one of unfettered movement, a material conception of globalisation must foreground – in the case of Fish Story, the sea – a space shaped by geopolitical and economic forces. This means seizing upon the visual and visible signs of those processes inherent to the flow of goods, made palpable by the dirt and grime, sweat and rust – the thick oily mess of capital.

Fig. 1 “Pancake”, a former shipyard sandblaster, scavenging copper from a waterfront scrapyard.

Los Angeles harbor, Terminal Island, California, November 1992 from Allan Sekula’s Fish Story (1989–1995).

Testing robot-truck designed to move containers within automated ECT/Sea-Land cargo terminal. Maasvlakte, Port of Rotterdam, September 1992 from Allan Sekula’s Fish Story (1989–1995).

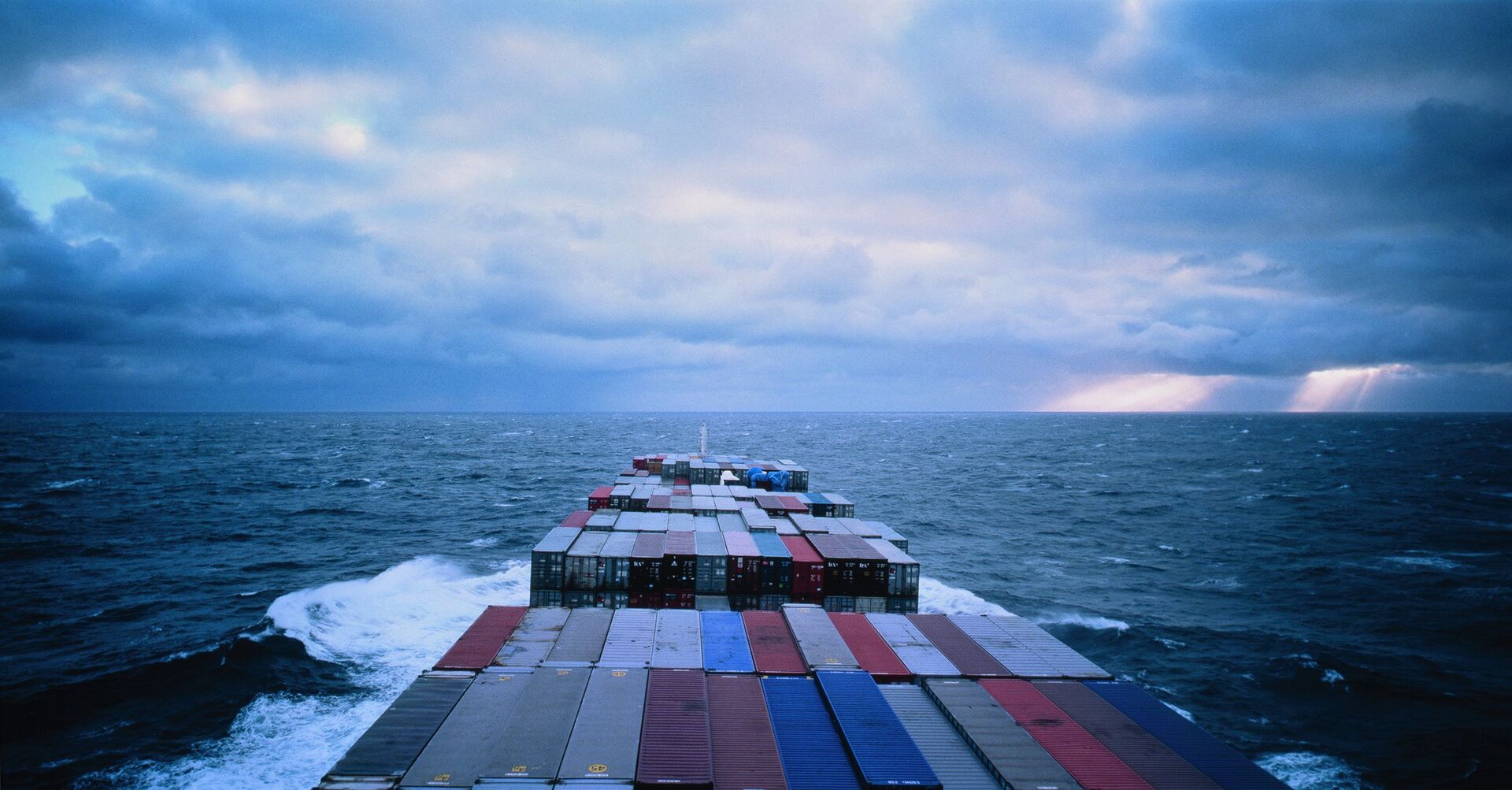

Fig. 2 Cover image, Fish Story (1989-1995).

The Global Surface, Interrupted

To lay bare the disorder, violence and decay embedded in the supposedly smooth global circulation of commodities, I suggest that some kind of friction is needed if the contradictions inherent to these flows are to be exposed and made palpable. Ethnographer Anna Tsing, in her book Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection, summarised friction-free movement as an illusion.Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 2005). Geographers Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift declared that a frictionless surface for the circulation of capital obscures the massive and very laborious effort that necessitates the production of the global surface.Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift, ‘Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance’, Theory, Culture & Society 24, no. 3 (2007): 5.

There are two photographs in Fish Story (see Fig. 1) in particular that encapsulate this concept of friction and how it can be deployed in photographic practice. In a short sequence of two images in the book’s first chapter (itself titled Fish Story), a lone woman sits in grimy, oil-caked dust, a tattered baseball hat haphazardly falling off her head. She’s wearing a pair of well-used canvas gloves, a wrench in one hand and other tools stuffed in her back pocket. She’s in a reflective moment of rest, but follow her gaze past the upturned hulk of rusting, obsolete machinery, past the boundary of the photograph and onto the next page, to the next photograph. Here, an automated robot truck carrying a SeaLand container does its job, undisturbed in a presumed fantastical technological utopia. Later, at the end of the chapter, we learn the woman’s name is Pancake; she’s a former shipyard worker, and she’s scavenging copper from a waterfront scrapyard in the Port of Los Angeles. And we learn that the truck, the object of Pancake’s gaze, is of the robotic, automated kind designed to move containers in the Port of Rotterdam (and displace labourers like her). On the left page: Pancake, someone who’s been left behind and forgotten by the instrumental forces of profit, mobility and compatibility. On the right page: the manifestation of a relentless march towards profit created by the desires of mobility and the necessity of innovation, technology and containerisation. Pancake reminds us that the frictionless economy is a lie. The cruel indifference of systematised shipping and the needs of globalisation is laid bare, its secrets exposed. Sekula called this mode of working ‘purposeful immersion’:

In an age that denies the very existence of society, to insist on the scandal of the world’s increasingly grotesque ‘connectedness,’ the hidden merciless grinding away beneath the slick superficial liquidity of markets, is akin to putting oneself in the position of the ocean swimmer, timing one’s strokes to the swell, turning one’s submerged ear with every breath to the deep rumble of stones rolling on the bottom far below. To insist on the social is to practice purposeful immersion.Allan Sekula, ‘Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea (Rethinking the Traffic in Photographs)’, October 102, no. 102 (2002): 7.

I prefer to view this as an aesthetic gesture not just of friction but rather more specifically one of rupture. To rupture something means that a fissure, breach or crack punctures something, releasing what’s simmering below the surface and causing its rise into something palpable and viewable. A rupture, then, is a way to reflect and recognise how social relations and labour structures are all knotted under a globalised schema, entwined in the muck and dirt of capital circulation. In other words, these ruptures insist on the social to unveil corporeal suffering for an aesthetics in and against capital. I propose, then, that to produce a rupture in the commonly viewed picture of globalisation, a crucial element needs to be introduced: namely, dirt.

Dirty Pictures and the Destabilised Image

Dirt has fundamentally intrusive power. It represents the physical Earth and binds us to the landscape. In Fish Story, this idea of dirt permeates every photograph; it’s in the cracks of the splintering ships, caked on the clothes of the workers and smeared on the surfaces of the shipping container. Dirt asserts the corporeal presence of the labourer, who’s so often occluded from view in a contemporary image of capital and globalisation (i.e., the Bechers, Burtynsky, Gursky, etc.) Further, dirt comprises our way of seeing the conversion of the landscape into a consuming machine via toxins and waste. Dirt, then, is ideological, allegorical and representational. However, before proceeding, it must be said that by ‘dirt’, I mean any kind of muddled state of matter, such as the particulates of dust to the moisture in fog, the oxidation of rust to the accumulation of dirt, any kind of element that could possibly contaminate or rupture the circulation of capital.

The artist and scholar Susan Schuppli coined the term ‘dirty pictures’, which she stated perform as double agents. A dirty picture moves beyond the mere representation of events, but the events themselves are integral to the creation of images. She uses the example of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 to illustrate her point: a ‘dirty picture’ shifts from the representation of that terrible event, depicting the vast swath of gushing crude, oil-soaked birds and dead fish washing ashore, to the very making of a ruinous image due to oil’s molecular transformation to refract light back at us, thus constructing a toxic, dirty image that we inhabit.Susan Schuppli, ‘Dirty Pictures’, in Living Earth Field Notes from the Dark Ecology Project 2014-2016, eds. Mirna Belina and Arie Altena (Amsterdam: Sonic Acts, 2016), 191-193. A dirty picture, then, is ascribed to the very processes of capitalism at its most unfettered, revealed in the cracks and fissures of its own rupture: the burning of coal smoke creates such a thick haze and fog that it modifies the visible spectrum of light; the toxic legacy of industrial seepage warps the landscape; a decaying factory oxidises from view the labourers who once worked there. Capital’s underbelly is exposed, made visible by the very dirt and toxins it churns out. In my own work, I’ve started to photograph the sites of production and the conduits of capitalism, namely the petrochemical landscape that ensnares the Port of Rotterdam and transforms the physical form of the Earth but has also altered the structure of life itself, physically and optically. This can be seen in how the material and financial flows of oil burrows itself into contemporary life, buried deep beneath the Earth’s crust as the carbon remnants of Pleistocene-era sea creatures, and the discharge of CO2 emissions contaminating our atmosphere. The Earth is a sentient being of petrochemical processes, lubricated by oil. The danger I face as a photographer is that my photographs could restage the toxic environment and become only beautiful, or even admirable, images, disavowing or fetishising the very processes that went into their creation. I want to create photographs that attest to the ‘brute reality’ of landscape as constructions of messy behaviour to ensure the ruptures of capital are apparent. A dirty picture, for me, refuses to be accepted solely on its compositional and representational mastery but is rather united in its registration of truth and beauty, or as Schuppli states, a dirty picture should ‘intoxicate and repulse.'Ibid., 191. In other words, a dirty picture deeply implicates us all into the very conditions that make up the circumstances of daily life.

Dear Bill (Gates)

I‘d like to conclude by looking at the cover image of Fish Story (see Fig. 2). Pulsing through the sea, an ordered stack of variously coloured containers rises from the deck and reaches out towards the vanishing point of the picture. There’s no indication of direction, just a perpetual unfolding of the ocean under a turbulent sky. Sunlight attempts to break through the darkened clouds. The photograph is evidently taken from the ship’s bridge; we look from up high into the empty space of a maritime world. I end with this photograph because I see it as an image that’s been ruptured, scrambling the rationalisation of the global surface. It’s a panorama, contrasting the stark industrial space of the ship with a sky just as wide. It’s elemental, redolent of the dirt and rust and muck of oil that I’ve argued is so necessary in visualising the global present, relinquishing a large part of the picture to the atmosphere and the storm clouds contemplating trouble. The photograph is ruptured by two crucial pieces of landscape – sky and location: the gridded determinacy of the container ship and the vague, unknowable quantities of the sky. The bottom half of the photo, below the horizon and punctured by the steadfast forward movement of the ship, is one of logic and perspective, a system of grids and vanishing points and delineation, a rational unfurling of capital’s logic and the dream of a frictionless enterprise. When looking skyward, up into the clouds, I see a picture that’s been split open, creating an indeterminacy that only the clouds know about. Here, the rupture is similar to the sun striving to materialise itself through the darkened storm clouds, an elemental burst that produces a ‘dirtiness’ between rationality and the forces of the geophysical, ensuring in visible means that the flow of capital isn’t slick nor untainted but rather the precarious forces that linger beneath are present, palpable and detectible. That, to me, is a dirty picture.

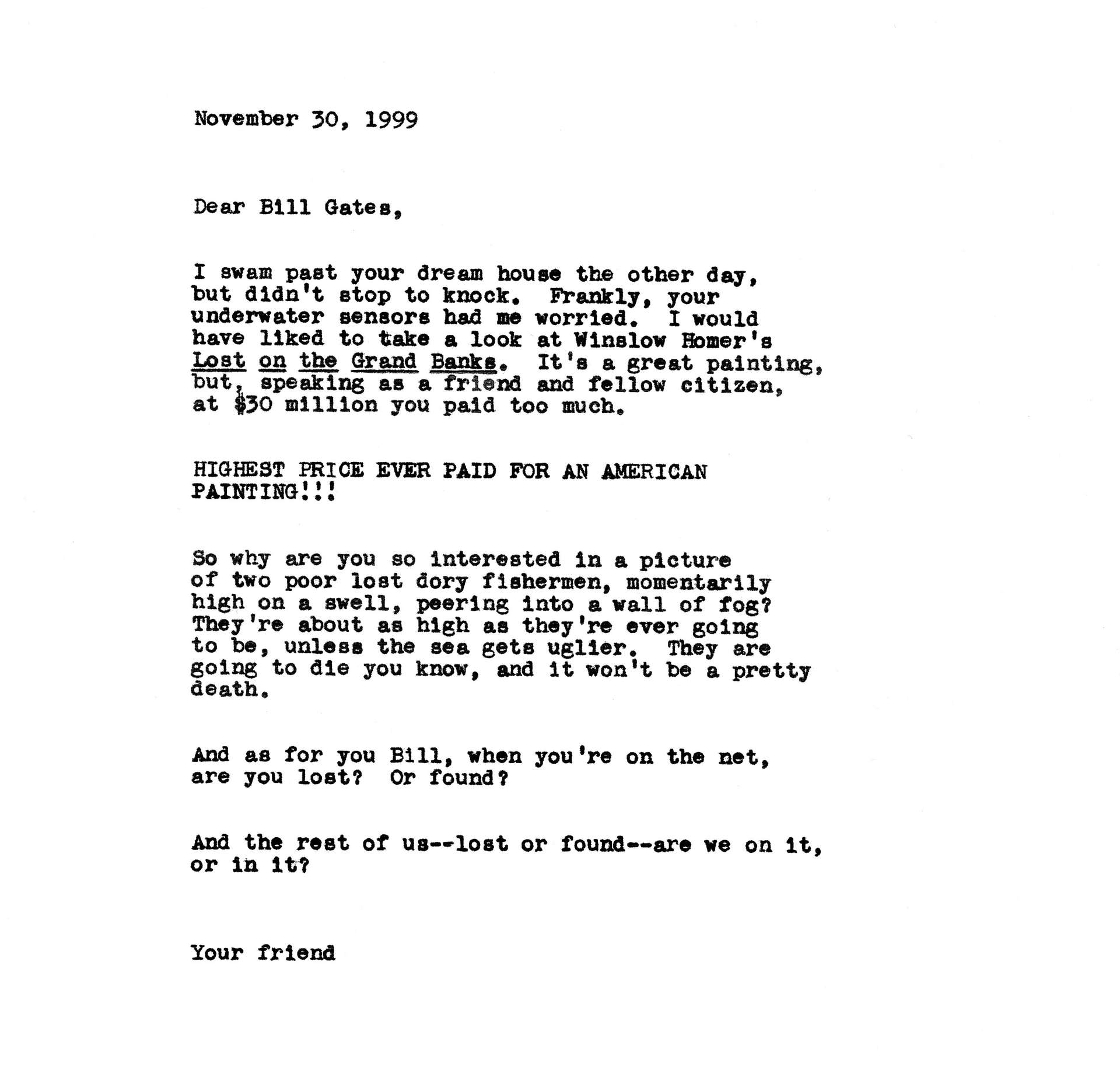

A dirty picture, then, is a (developing) method I use to complicate the supposed unfettered flows of capital circulation. It destabilises photography’s desire to fetishise and abstract infrastructural landscapes, creating epistemological uncertainty by rupturing the fundamental agents that shape our social and cultural behaviours. A dirty picture is one that implicates us all in the toxic legacies of capital, one that’s based in the carbon rather than digital world. By getting dirty, a certain level of transparency is reached in that what most would prefer to be forgotten or marginalised is in fact thrust into view, not inert or still, but rather a spectrum of experience, ethics and aesthetics. A dirty picture gives rise to the question that must be demanded today, in that the common sensical and rational is anything but. Of course, Sekula said it best when he wrote a letter to Bill Gates (see Fig. 3). Near the end of it, he said: ‘And as for you, Bill, when you’re on the Net, are you lost? Or found? And the rest of us – lost or found – are we on it, or in it?’Allan Sekula, ‘Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea (Rethinking the Traffic in Photographs)’, October 102, no. 102 (2002): 4. Bill never replied.