Fluourescent Fool’s Gold, digital photograph, 2018

Dialogues on Gold: A Conversation about Women and Extraction

Edited by Marie-Kathrin Blanck, Yasmin Meinicke, and Iris Sikking

In this conversation, visual artist and educator Lisa Barnard and critical theorist and author Macarena Gómez-Barris discuss the capitalist-colonialist heritage of the exploitation of natural resources in South America, in which they have a parallel interest.This conversation was recorded on 30 June 2021 via Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity. Both have a practice dedicated to topics that illuminate the connection between women’s participation in extractive economies and the impact of such industries on the natural environment. They touch upon the invisible dimensions of women’s work, the human and environmental impacts of extractive capitalism, photography’s relation to truth, and the responsibilities of Western photographers in documenting or representing non-Western subjects. For this conversation, they take Lisa’s latest project, The Canary and The Hammer,The Canary and The Hammer exists as a book and an exhibition, as well as an experimental, interactive website that presents the extensive research that went into the project: http://www.thegolddepository.com/.as a starting point, and draw on insights from Macarena’s extensive work on the topic, including in her 2017 book The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives.Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Duke University Press, 2017).

Lisa Barnard & Macarena Gómez-Barris in conversation

04 feb. 2022 • 16 min

Disney Figurine, porecelain figure, coated with Fairtrade SOTRAMI gold leaf.

Intertwined stories, personal connections, and positions of power

LB: I suppose my practice in general is first and foremost looking at language and narrative in relation to photography. The images, the ideas that I’m interested in, are around the intersection of photography and capitalism and the speed of imagery in relation to new technologies. The starting point for The Canary and The Hammer was Pocahontas. I was keen to make a body of work that had a female protagonist, and Pocahontas is apparently buried quite near where I was brought up, about ten miles away from my hometown in Sevenoaks in a place called Gravesend. So that’s really where I started. The project contrasting her narrative with the false or Disneyfied narrative was interesting for me in relation to photography and its connection to truth. And certainly, photojournalism and documentary purport to have this objective or indexical relationship with reality, but truth is slippery. The world is far more complicated and fragmented, and it’s always difficult as a researcher to get to the heart of the matter. My work embraces a fragmented strategy in order to talk about the complexities of the world in relation to photography. It explores the relationship between visual imagery and the exploitation of land, the subjugation of women, capitalism, and conflict.

MGB: It’s gold mining. Your work attends to the origin story you’re referring to here, a story about female subjectivity and Indigeneity. You’re trying to unthink the colonial version of the story of Pocahontas, or the Disneyfied version, and that’s a very interesting project. I was trained as a sociologist and academic, and more and more I think of myself as a theorist and creative writer. And I write on themes of memory and ghostly hauntings of the colonial past. In my book The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives, I attend to mining, petroleum extraction, spiritual tourism, and other economies of extraction and eco-tourism, and to anarcho-Indigenous feminisms. I look at five sites of majority Indigenous regions. It’s a book that took me about ten years to research alongside Indigenous communities in Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. At the time, I didn’t look at gold mining, but I just finished a novel that’s set in a gold mining region. I grew up in a place in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, where the first gold was found in 1848/1849, in what became Sutter’s Mill. Though it’s often unstated, this is a Maidu Indigenous region. And I’m a daughter of a political exile from Pinochet’s Chile, and we arrived in this white settler terrain that I couldn’t name as such at the time. The novel follows a young Brown girl who hears the haunting echoes of this settler period in a place where many massacres took place against Indigenous women and children. So gold extraction, economies of extraction, and white settler histories are very much intertwined with my own complex subjectivity of here and elsewhere.

LB: And I think that’s always difficult with subjects or topics that have such gravity, is how can you fictionalize those positions unless you have a sort of autonomy – unless you have a connection, a direct connection, then what gives you the right to fictionalize something? You have no voice about it, really. So I think that’s why photojournalists and photographers who have dipped into places, used their camera, and then dipped out again have made work that underpins that position of power – the colonial, occupying gaze that photography can have with community work. I think writing a novel is by far the best way to talk about things; it’s honest and doesn’t purport to be truthful. It’s a really difficult time for photography right now in relation to the issues we’re talking about. Because documentaries on Netflix are absolutely fantastic, and interesting ways to delve deeper into topics, but for me, they don’t ever present the complexities of our relationship in the West to these environments. They don’t talk directly about the responsibility that we have in viewing anything, whether it be Netflix, a book, or a photograph. These works don’t reflect the responsibility that we have as viewers to interrogate authenticity and the problem inherent in the relationship between white power and the Indigenous person. That’s what the camera brings straight from the get-go. It’s very difficult! If I go to Peru, I’m in a position of power straight off.

Mountain Landscape, Orotone made with Fairtrade Gold leaf from SOTRAMI with Kozo Washi Gampi paper, 14cmx12cm

MGB: I do think that those positions of power have been completely overturned the very moment you take out your camera. The kinds of relationships artists have to communities don’t have to be these kinds of pure relationships. I don’t think there’s a privileged position, necessarily, either when you are with the community or when you are actually part of the community. Sometimes being an outsider allows for a different entry point into extractive economies, and it can be generative when one is conscious of one’s positionality, as you are. It allows for a different viewpoint that de-familiarizes spaces that are normalized by extractive industries. The point is to create a certain degree of visibility and attention to invisible subjects and those working in the shadows of capitalism, as many women and children do globally.

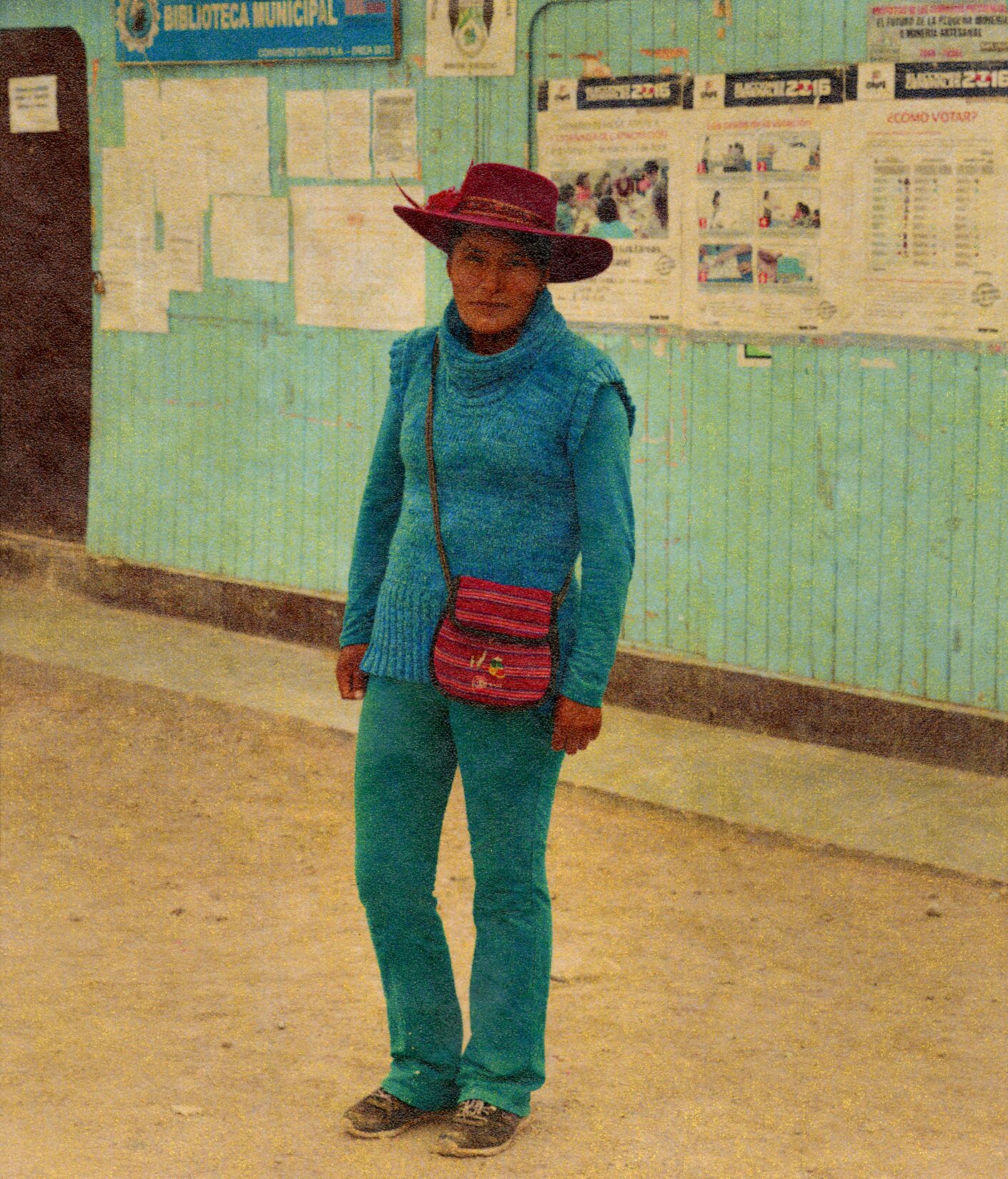

The Sweat of the Sun – the Pallaqueras

LB: These images here show some of the women artisanal miners who scrabble around in the tailings for rocks containing gold. Colloquially, they’re known as Pallaqueras. The images I took of these women were the fuel for what I wanted to do; they became orotones. The images are backed with fair-trade gold leaf from the SOTRAMI gold mine as a way to give value to the photograph, and also to direct the viewer to the materiality of the photograph so that they think about photography in relation to mining – but also to try to find a way to give value to the women’s hard work, which is often overlooked. So it’s a twofold or threefold way of trying to attest to some of the problems that are inherent within documentary photography and photographing in communities – by using the very thing that they helped to make, but also thinking about how photography is inherent within capitalist frameworks. Without visual imagery, capitalism doesn’t exist; as Susan Sontag said, a ‘capitalist society requires a culture based on images’.Susan Sontag, On Photography (Picador, 2001). It’s part of the machine of capitalism. And the art world is complicit in that, documentary photography more than anything else. When I go to a place, it’s really like taking notes in order to write a novel. When I get home, that’s how I use the work that I make.

Sandra, a member of the pallaqueras

MGB: What strikes me in this artwork is the use of elements and gold as material that reflects the working and life conditions of the women. These are the women and children that I referred to earlier, who for instance work in slag piles and in the overflow of toxic surplus. And often, because they go below the radar of the masculine, patriarchal gaze of capitalism, they can organize in ways that bring attention to their plight. Often, their labour work is informal and unpaid, as we know, but they are also able to use their positions as women in the very homosocial male mining environments. For instance, women organize hunger strikes or refuse to do the work for certain wages. I don’t know if this has been true in northern Peru, but throughout the coercive colonial and modern histories of these extractive sites, it’s certainly true. The fact that you document these women through your visual art practice is really, really important here. There’s no pretence of it being an insider’s view. It’s clearly an outside view. And the way that you bring together, or agrupar, the collective space. It’s quite powerful

LB: What I found very interesting was this idea of mythology: if women go into the belly of the earth, the gold retreats into the mountain. I heard that so many times and all I wanted to say was, do you not realize that this is keeping you in your silence? That’s male patriarchy. That myth perpetuated by the community that you’re working in is part of a tradition of subjugation, not just by the Western gaze but by the gaze within this environment. The men are allowed to go down and make all the money, and the women must scramble around in the tailings because it’s considered unlucky if they go into the belly of the earth. And for me, that wasn’t something that I felt that I could talk about or communicate because I was bringing my Western sensibility to this idea of control. Rebecca Solnit talks about this invisibility and silence that pervades women’s lives wherever they are in the world, but particularly in communitiesRebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (Granta, 2017). – in my opinion, in this particular community. The difference with SOTRAMI is that because it’s a fair-trade gold mine – it was considered the first fair trade gold mine in the world – the women are actually allowed to keep the rocks they find. There’s hardly any gold in them and they’re processed separately to the men’s rocks, and the women then share between themselves the money that’s made. It’s not very much, but it makes a small difference. They can do this flexibly in between feeding their husbands, picking the kids up from school, making food in the square for the men in the evening, and so on. Historically, women have worked in the service industry, but their wages are nothing compared to what men make. But it is far more stable, which they need to bring up their families. This idea of women being totally integral to the system of capitalism, but through other means, is what Bertold Brecht discusses in Mother Courage and Her Children, although Brecht’s protagonist is making money in the theatre of war. Women have a huge potential to make money, but it’s really hard holding down multiple jobs and being creative entrepreneurs when all you’re doing is surviving.

Capitalism and motherhood

MGB: I think you’re touching on such important and profound issues. These economies of care exist within a capitalist system that depends upon exploiting women and children. Yet without this population, this labour, there would not be the reproductive element that capitalism needs in order to fuel the mining economy. There are really important connections that you’re making across the Americas and to California as well, and across women, including white women settlers. I agree with you that there’s this invisible dimension.

LB: You know, my work is really a reflection on, I suppose, my voice, my history, and my relation to the people that I meet along the way. I was recording interviews, and a vast majority of the conversations that I had were not positive. Now, what do you do with that? That becomes very difficult, because then you’re talking about suffering and it’s very uncomfortable. I felt that I had no right to comment on their suffering. It’s such a predictable and problematic narrative within photography, in so many ways. I was only there for two weeks with the Pallaqueras. I don’t know what to say about that, really. I don’t know what I think about it. Ultimately, I couldn’t help, as it’s just that other women’s lives are tough, and I’m privileged. I made sure I sent photos. That’s the big thing that you do in documentary, you provide them with a photo. And it’s like, right, I’ll make sure I do that. So, of course, I did that. But ultimately, it just seems that the only thing that I can do is talk from my position.

I’ve been a single mom since my kids were relatively small. I’ve never been able to have that luxury of being able to just bugger off and put myself at risk, especially when I was doing a lot of work on conflict at the beginning of my career. I had to find a different strategy to talk about things, because I wanted to talk about these things, but ultimately you’ve got a responsibility to your children, don’t you? There are so few female documentary photographers with children, you can count them on one hand. So I’m very interested in mothers generally in relation to the arts and business. I’ve made a lot of work about mothers in America and their conflicts, and the women in Santa Filomena in many ways were no different. The narrative that I was hearing when doing the interviews was around being in debt, or their husbands had gotten into trouble with debt in Lima and they were escaping. Or they were trying to raise money in order to put their children through better schools. These are very familiar stories and I could, in some small way, relate to them. So that’s why they did five jobs. But ultimately, you do five jobs and you’re still scraping by. The men are getting loads of money, as they have access to the gold mine, and then just pissing it away on a Friday night. Nothing changes, right? It’s like going back to the beginning of the gold rush – that’s the same narrative. It’s no different. And that’s quite difficult to address, isn’t it?

MGB: Yes, absolutely, and I think you bring very real and material questions to the foreground. To me, it goes back to that question of care. What is it about the position of a mother? I gave one narrative, right – the one about gender and reproductive labour for global capitalism. But what, as an artist, have you uncovered about these women? There are other artistic layers there about representing these women’s lives in a complex way. I mean, you’re talking about suffering and the un-potentialities of capitalism, right?

LB: There’s not much to uncover, apart from the details of the difficulties of living in such a place, and ultimately it’s impossible to rely on information that was told to me, as it’s all so loaded. They’re feeling vulnerable and performing for me when I’m talking to them, and I’m bringing my Western and white middle-class female gaze. There’s nothing truthful about that relationship right from the start, apart from the fact that we’re mothers – that’s the only thing that we have in common. And that’s what we mostly talked about. And that’s a very powerful thing, I think. We played volleyball a lot and that seemed to be the most honest thing that happened there. I was rubbish!

MGB: I think that this is part of your lens – there seems to be an effort to work with these women and to try to see their lives rather than objectifying them.

Biodiversity

MGB: I want to take it to this question of biodiversity. I’m quite critical of sublime aesthetics in extractives zones. There are artists who make terrible and destroyed spaces beautiful, which is quite common, actually, in documentary photographs. It’s another version of landscape painting. And of course, it writes out precisely the racialized bodies that are doing the work of capitalism, which you write in. But you are also following the kind of metal itself, and you show its colours, its dimensions, and its materiality. And this is also quite interesting to me and something I do in my own creative and academic research and practice. It’s not just attending to and being caring of the women and their maternal roles. For me, following the material of gold and the land, as we do in our work, allows for fluidity or a non-boundary between, say, the Earth – madre tierra – and the human, or the more than human, dimensions. When we talk about biodiversity, is it just about spaces that have very high insect and mammal counts? Or is it also about the kind of practices that attend to the geology of the land and its history, and that actually generate new ways of seeing and perceiving? I thought of that generative space when you were talking about seeing an unconscious and what’s hidden in the scene. But I’m thinking of it more in terms of how you’re raising the material situation and placing the worker, the female worker, there, but also showing what I refer to as a non-extractive view.

LB: Yeah, the whole relationship between biodiversity and materiality is so fascinating. I was working with this fantastic woman at the University of York who co-runs this organization called Phytocat, and they’re researching phyto-mining. They go into extraction zones and they plant willow to draw up the metals and the poisons and the toxins from the earth. They’re then burned, and any ore is removed, catalysts are made from the ash, and the soil becomes cleaner. The local population can potentially make a lot of money by selling these catalysts. They’re doing a lot of work around this in New Zealand. And I thought of that whole idea that Ursula Le Guin talks about, that we are all mountains. [Editor’s note. Le Guin writes, ‘We are volcanoes. When we women offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all the maps change. There are new mountains.’Ursula Le Guin, Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (Grove Press, 1997).]

Women are part of the land, and they’re these strong and powerful forces. I thought that the connection between using plants and extracting metals and materials from the Earth reflects the way that women are connected to the Earth. I thought that that was just such a lovely connection.

This is an example of what I try to explore in fragments and different layers of The Canary and the Hammer. I try to see and then offer a view through photography. I’m interested in what Walter Benjamin termed the ‘optical unconscious’ – the camera revealing what’s hidden from view. What is not made visible is actually the information that’s important in my work. The image is a conduit to discuss what’s invisible, and that’s all. The layers and the nuances within narratives, the layers that you can address, the history; that’s one of the main concerns of my work. I try to point out and ask questions rather than to answer them, and to ask the viewer to develop their own relationship to the work rather than give them a presentation of facts, because there isn’t just one truth. The history of the world is complicated and, in my opinion, requires a presentation that embraces that.

All images taken from the chapter 'Sweat and the Sun' from the book The Canary and the Hammer, Lisa Barnard, 2018

The Canary and The Hammer exists as a book, as an exhibition and as an experimental and interactive website that presents the research for this project: http://www.thegolddepository.com/

This contribution was originally published in English in the third printed edition of Trigger on 'care' in collaboration with the Biennale für Aktuelle Fotografie, in November 2021. In Trigger #3: Care, contemporary forms, coalitions and 'minefields' of care are examined from various photography practices. Rekto:Verso published a Dutch version here in the context of their issue on care, published in December 2021. Trigger and rekto:verso thus establish some connections between their respective editorial approaches to the same comprehensive theme.