Dear Cyanobacteria,

It has been three years since I wrote you my first letter. It was a one-sided declaration of love and an attempt to generate closeness between us. Although no reply letters were ever issued, I have become your student, wanting to speak in relation with you, ‘nearby’ instead of ‘for’ or ‘about’ you. Or, as Trinh T. Minh-ha puts it very precisely, ‘a speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it.Trinh T. Minh-ha, Cinema Interval (New York: Routledge, 1999), 218.’ In doing so, I will try to stand next to you and look in the same poly-directions.

Over the past three years, your colours changed from fluorescent green to all shades of brown, to blue and yellow, to dark green and white, to fluorescent green again. Bubbles appeared in and above your habitat; foam formed on top of your liquid self like a head of beer. Impressive biofilms were created in your presence, sometimes all over the border of your habitat, but sometimes only on the daylight side of it. A fascinating oily layer may lie on you from which a slimy dark secretion builds up above the edge of the liquid you live in. I have kept journals of how long you stay afloat and when you descend, whether you clump or glob, if you stick to the air hose or to the rim of the flask. This last sentence might be more ‘about’ than ‘nearby’ – I apologize if I transgress a boundary here. On the other hand, perhaps it is inevitable to occupy a space of ‘aboutness’ within more-than-human relationalities?Jan van Boeckel, personal communication, 6 July 2023.

Time and again, I pricked my finger and dripped a few drops of my blood into your habitat. That may sound a bit heavy-handed or even colonially violent, but blood has always been known as a fertiliser. Some Indigenous cultures celebrate menstrual blood and consider it a symbol of fertility, and amongst some feminists, it is quite common not to flush away menstrual blood but to use it, for example, to increase the fertility of the soil.Renata Moura, ‘¿Por qué algunas mujeres pintan sus rostros con sangre menstrual?’, BBC News Brasil, 23 July 2019, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noti....

Moreover, I am almost certain that the witches who ended up on the pyres in early modern Europe also carried this knowledge with them.

Dear Cyanobacteria, in all this time we’ve spent together in the past few years, you have become such an important part of my life. Three non-reciprocal years: it’s not even a pinprick in the three billion years you’ve lived and died on this planet. Three thousand million years. . . Three years is less than a hundred million seconds. . . . I still know so little about you. . . .

I end this letter with the same words as my first letter to you:

In great admiration and gratitude,

Risk Hazekamp

Story #1: The Cunning Ruse of Intelligibility

A large part of human life is about understanding, about explaining complex things in structured ways so we know what to do, what to think, how to act, and especially why to act. Most humans are good at simplifying complex matters: it gives a sense of stability, functionality, and control.

But human beings are not stable, not functional, and not in control. And life itself certainly is not either. Life is a celebration of complexity and wonder, chaos, inconsistent thinking and acting, instability, discomfort, not knowing, fear, and much more. And it is precisely these states of being that are often erased, in exchange for a warm blanket of make-believe control wrapped around our naked human bodies.

A question that has been occupying me for some time is how I can embrace complexity and, in line with this, precariousness (in the Butlerian sense of the word)Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009), 14. in my artistic practice –and in doing so, give positive meaning to these practices that are often labelled as negative or unproductive or both. Introducing precariousness as a centre position into my artistic practice means I must first review the very foundation of my practice, which in my case is analogue photography.

In the early days of analogue photography, inexplicable supernatural or spiritual photographs arose that could not be explained by the viewer. Magical processes took place: the camera managed to capture ghostly apparitions of deceased loved ones, ancient ghosts wandering through rooms or auras of people floating around the body of the portrayed like energy waves.Simone Natale, ‘A short history of superimposition: From spirit photography to early cinema’, Early Popular Visual Culture 10, no. 2 (May 2012): 125–145.

This sense of wonder and complete fascination with the unknown was soon exploited and capitalised on, for example, by the photographer couple Hannah and William Mumler. Subsequently lawsuits were filed and experts came to scientifically explain the phenomena that had been captured. Everything turned out to be caused by long exposure time(s), double exposures, or chemical processes. Case closed. In the 748-page classic ‘A World History of Photography’, author Naomi Rosenblum only spends one paragraph on the phenomenon. She writes: ‘An exceptionally popular subject . . . was the “spirit” image. Dealing with some aspect of the supernatural, . . . these pictures were made by allowing the model for the “spirit” to leave the scene before exposure was completed and by resorting to complicated techniques. They were taken seriously by many photographers and appealed to the same broad audience for whom seances, Ouija boards, and spiritualism seemed to provide a release from the pressures caused by urbanization and industrialisation236–237.

Ghost Landscape, analogue B&W photograph (double exposure), 1990s.

Nowadays, in most articles about spirit pictures, the first sentences make it very clear that all supernatural appearances in photographs are quite easy to explain technically. Hardly anyone believes anymore that the soul is peeled off like the skin of an onion when someone takes a picture of the Other. All we see now are the afterimages of the days when the idea was prevalent that supernatural energies could be captured through photography. But why do we no longer want to believe in these images? And might the explicable part of them actually be of less relevance? One could even argue that we lose more than we gain by only expounding their technicalities. It is a form of reassuring knowledge, a kind of knowledge that gently rocks everything back and forth, and, contentedly belching out after everything has been consumed, invites sleep to take over. With everything explained and described and understood, eyelids begin to feel heavy, and we might miss the Otherwise(s)Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Between Gaia and Ground: Four Axioms of Existence and the Ancestral Catastrophe of Late Liberalism (London: Duke University Press, 2021), 140: ‘The otherwise are those immanent forms that lie within social projects outside the dialectic and difference of Self and Other.’, the far-reaching possibilities that arise beyond the explicable.

But meanwhile, countless cracks and fissures, chinks and holes seem to be appearing in the modern world, in the project of modernity. These cracks, which many decolonial scholars speak aboutWalter D. Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh, On Decoloniality, Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (London: Duke University Press, 2018), 81–98., stem from different forms of knowledge production to understand our day-to-day journey: To read what is not written, to hear what is not told. To see what is invisible and to listen to the unspoken, for only by embracing the not-knowing can we go beyond ourselves. It is in this crack that I see this first attempt to unearth some forgotten, lost or not-yet-told stories ‘nearby’ Cyanobacteria.

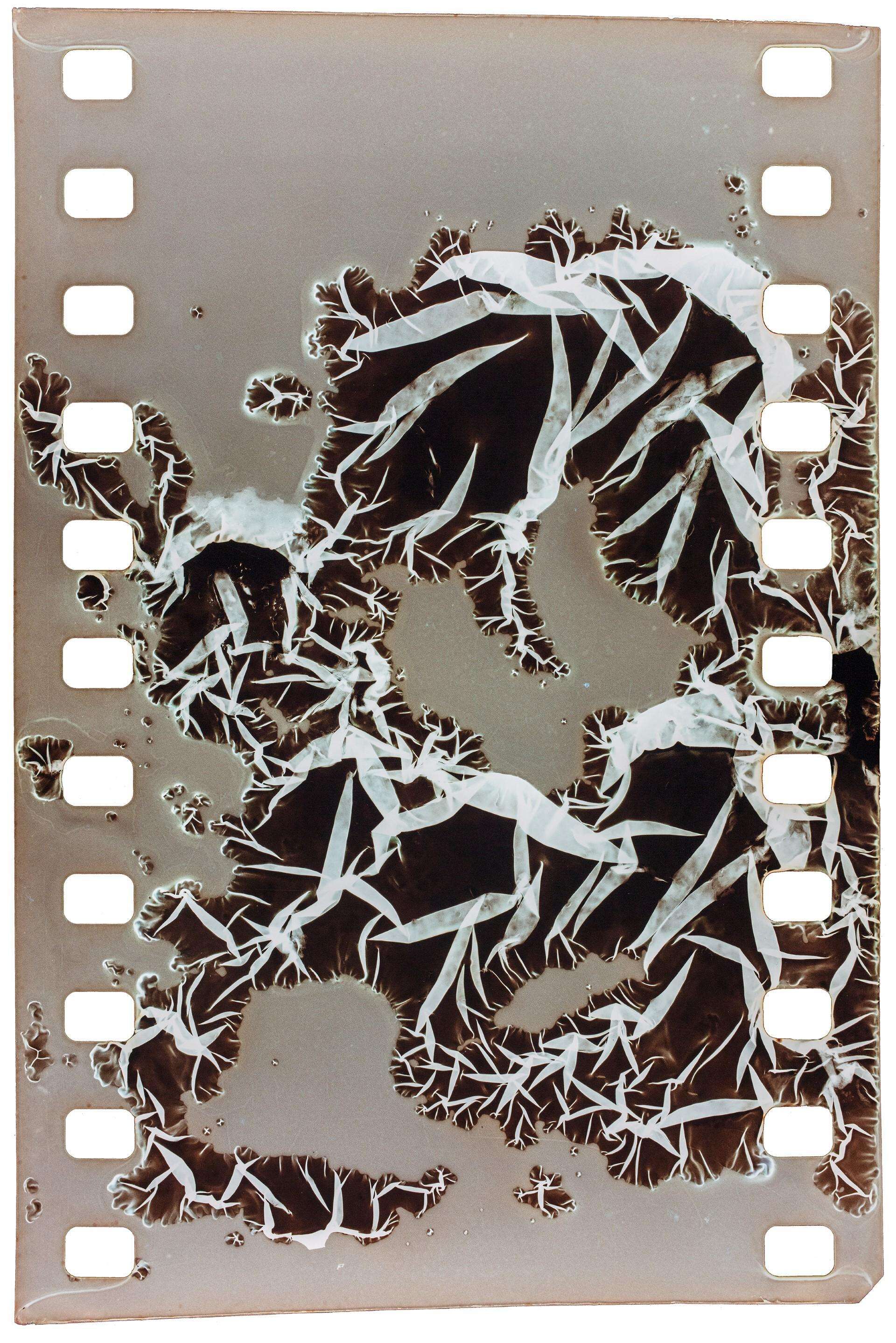

Pigment, 2023.

Story #2: The Border of the Object | Hereish

The quasi-event is only ever hereish and nowish and thus asks us to focus our attention on forces of condensation, manifestation, and endurance rather than on the borders of objects.Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (London: Duke University Press, 2016), 21.

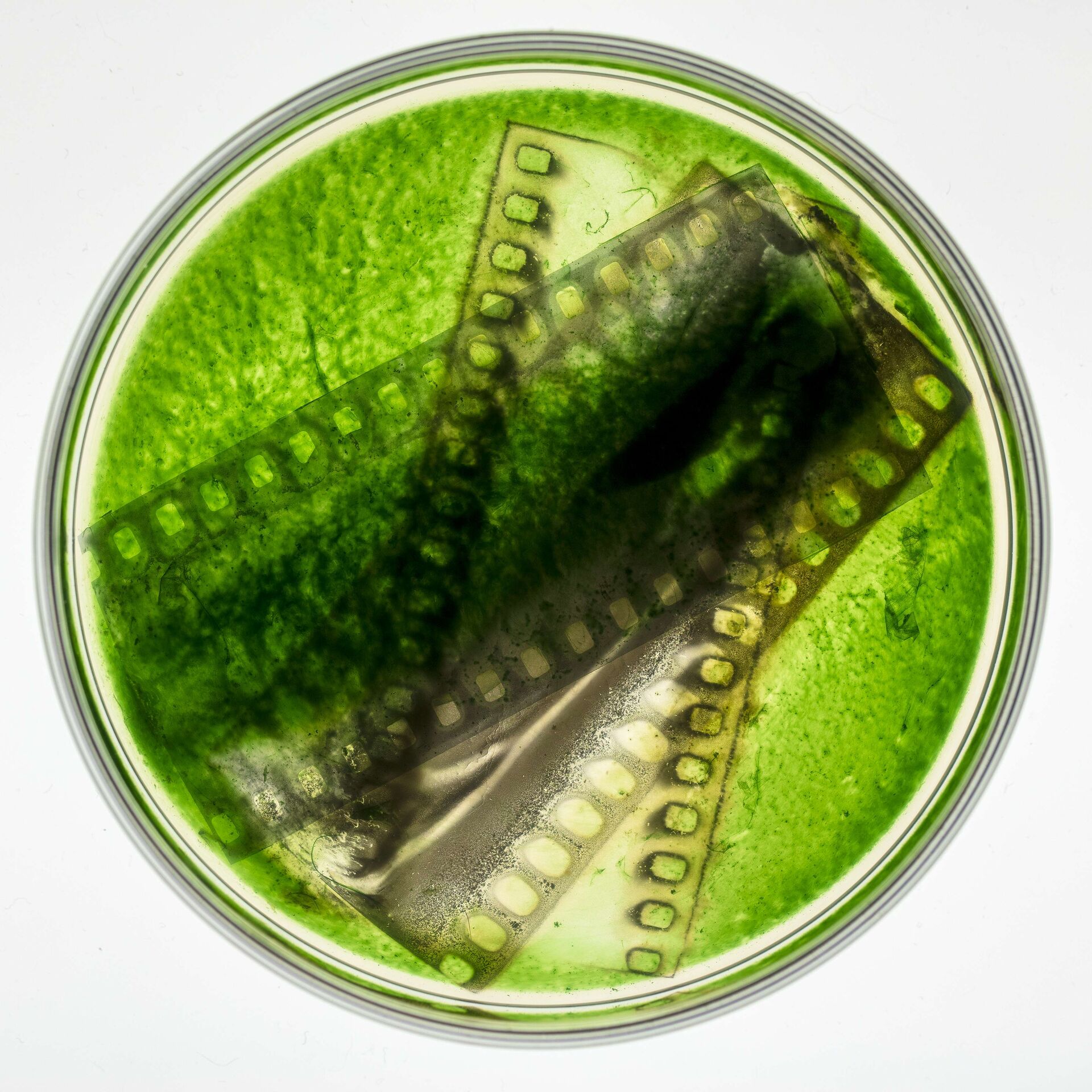

Throughout the summer of 2022, I roamed Belgium and French flea markets to search for large glass flasks. All of them were gathered in my studio, where, step by step, I introduced small amounts of Cyanobacteria into them. Gradually, the Cyanobacteria flourished in their new glass habitats until, after a few months, my studio was filled with liquid green. ‘We’, the Cyanobacteria and I, were invited to participate in that year’s autumn exhibition at Stroom, an art space in the centre of The Hague, close to where my studio is. With the flasks sloshing on the back of my bicycle, I transported them filled with green flourishing living cultures. I proposed to build an installation in the display window, a narrow space that sits between the street and the actual exhibition space.

In reference to the photographic dark room, this became a photographic light room. Here, Cyanobacteria interacted with photographic film material. As a new approach to analogue photography, Cyanobacteria dissected and dissolved the gelatine layer of the film emulsion, leaving bactographic traces in it. During the more than three-month duration of the exhibition, I kept a close eye on the Cyanobacteria cultures. Every other day I would visit them, sometimes give them some extra fresh liquid food, or I would do some maintenance on the installation. For example, I would cut off a piece of an air hose if it had become clogged, to restore the air supply and thus the movement inside the flask, the Cyanobacteria’s habitat.

Beforehand, I was seriously worried whether the Cyanobacteria would survive the challenging conditions of Stroom. But to my absolute delight, almost all the flasks preserved a beautiful green colour throughout the exhibition, green being the vibrant sign that a culture is flourishing. Only one bottle did not. After two or three weeks, the colour of this particular bottle shifted from deep green to a translucent yellow – as if all the Cyanobacteria had suddenly disappeared, leaving only a watery substance with some mush at the bottom of the bottle.

When it happened, I was shocked and waited anxiously for all the other bottles in the installation to drop as well. But they didn’t: the other bottles retained their green colour. Why had this one bottle changed? Perhaps I had made a mistake with the liquid food and given the Cyanobacteria too many metals? Or maybe too much sunlight was reflected via the windows across the street? I decided to replace this one flask and give the – at least visually – disappeared Cyanobacteria some rest in my studio.

And thus, another flask with bright green Cyanobacteria entered the installation on the exact spot where the other one first stood. But after a few weeks this flask also shifted. And again, only pale, yellow-coloured water remained from what had first been a thriving Cyanobacteria culture.

I checked the temperature, the pH value, air supply. Looked at the amount of light during the day, checked the photographic material inside the flask, the size of the bottle neck, the thickness of the bottom, even how I had taped the information on the flask, all possible ‘othernesses’ of that specific spot in comparison to the rest of the installation, but I found nothing. So, once again, I replaced the flask.

And it happened again! Exactly the same thing happened again. I was devastated and at the same time angry at my own stubbornness and persistence. I fully fell into the trap of wanting to meet artistic and institutional expectations.Marnie Slater, personal communication, 11 July 2023.. Not even the title of the installation How Do We Take Care of Our Failures? had been able to dissuade me from this. The Cyanobacteria themselves had clearly communicated that they could not be alive in this specific place. And what did I do? I tried to interpret it. Why could I not accept that Cyanobacteria did not stay alive in this place? Perhaps their non-living state was more suitable and sustainable for them, or maybe it was all about the two weeks it had taken them to transition from living to non-living?

Story #3: On How to Live a Non-Living Life

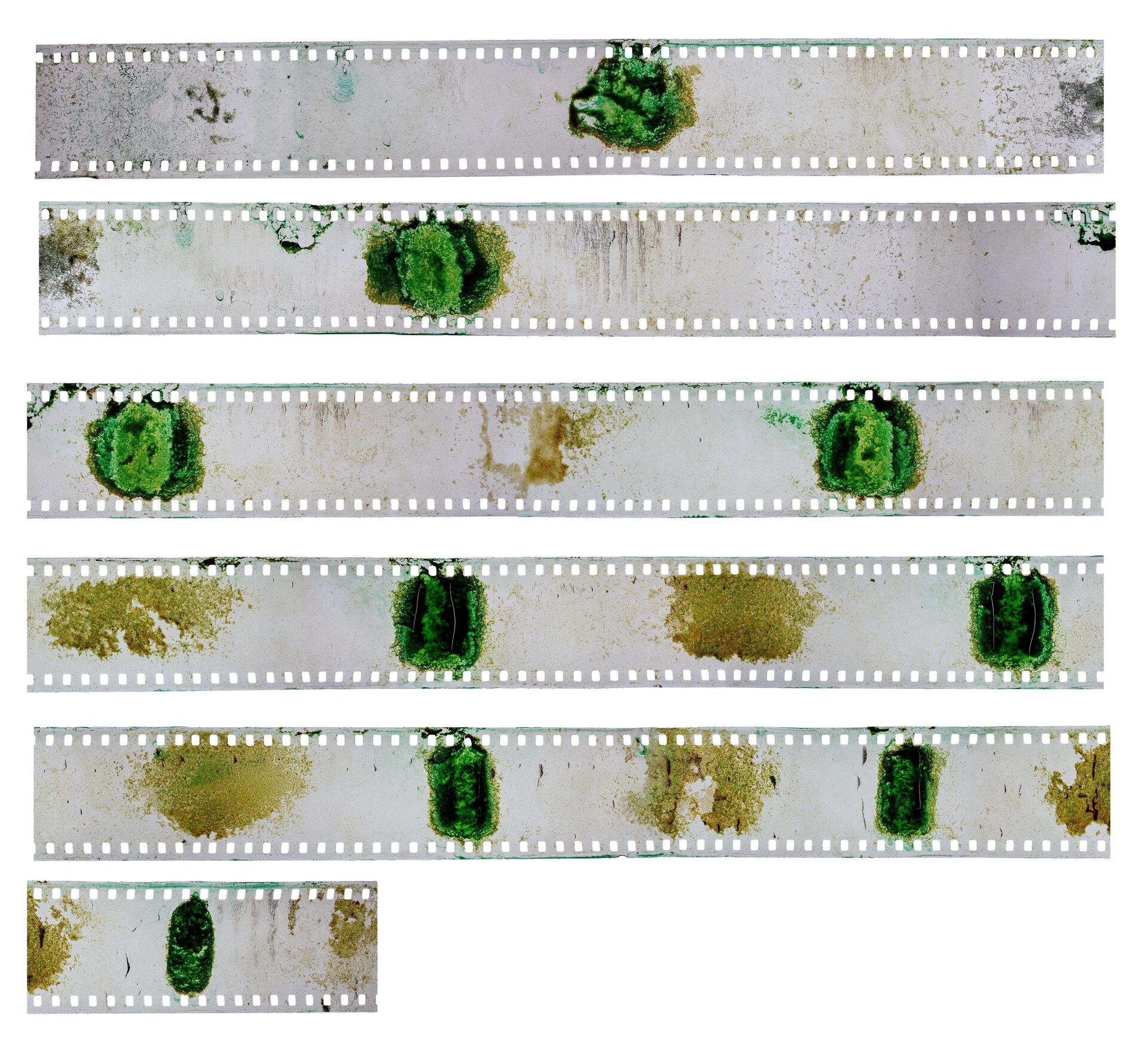

B&W 35mm film roll dissolved by Cyanobacteria in display window at STROOM The Hague, 2022-2023.

Story #4: Where Is the Desert When Your Land Is Made of Water?

Modern Man, the make-believe leading figure of the Modern Era, loves to discover and explore the so-called inanimate parts of the world, the great heights and the immense depths, where life is supposed to be absent and inconceivable. At sea level, the place best known as inaccessible and virtually unliveable would be the desert. Look at the desert and it seems a fait accompli that nothing will grow on these vast sands. Elizabeth A. Povinelli positions ‘the Desert’ as one of the symptomatic figures within her concept of ‘geontopower’.Elizabeth A. Povinelli, ‘Acts of Life: Ecology and Power’, Art Forum, summer 2017, https://www.artforum.com/print/201706/acts-of-life-ecology-and-power-68689: ‘Geontopower does not operate through the governance of life and the tactics of death but is rather a set of discourses, affects, and tactics used in late liberalism to maintain or shape the relationship between life and nonlife.’

It is based on the idea that, in late liberalism, a natural and fundamental distinction is made between Life and Nonlife, between the lively and the inert. For Povinelli, geontopower is not ‘merely a crisis between Life (bios) and Nonlife (geos, meteoros). Geontopower is a mode of late liberal governance. And it is this mode of governance that is trembling.’Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (London: Duke University Press, 2016), 16.

The Desert is the silent witness of the separation in which bios (Life) is exalted as the only thing of value and geos (Nonlife) is seen as a product. The Desert represents all things denuded of life and is therefore without activity or agency. As Povinelli shows us, this dichotomy between bios and geos is only able to turn habitats into resources and ecosystems into commodities. Caught in this all-consuming colonial matrix of power,‘The colonial matrix of power’ is a concept first used by Aníbal Quijano; ‘modernity/coloniality’ is another expression of the same concept. It refers to the way in which the concepts of modernity and coloniality are inseparable. See also Aníbal Quijano and Michael Ennis, ‘Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America’, Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000): 533–580.Modern Man fantasises about colonising the Moon and Mars, about deep-sea mining and bringing the desert back to life through the deployment of innovative techniques and the ‘right’ scientific knowledge.

B&W 35mm film strip dissolved by Cyanobacteria, 2021.

B&W 35mm film strip dissolved by Cyanobacteria, 2021.

From a Cyanobacterial time-perspective, we encounter a completely different picture. Cyanobacteria have lived and died on Earth for more than three billion years. In Cyanobacterial time, bios and geos are parts of one set of living and non-living substances that constantly merge into each other and together form a planetary collective. Life and Nonlife interact and mingle and – this is probably most important – completely depend on each other to constitute a shared continuum.

With the dividing line between living and non-living made transparent, a parallel world opens up beyond our perception where movement and stasis become concepts that are no longer exclusively related to human rhythms. Or as marine microbiologist Karen Lloyd puts it: ‘I love the idea that we are trapped in our timeframe and way of thinking and . . . that there is this overlay of another world, that is the same world, that is with us, but that . . . there are multiple ecosystems who are not playing by the same time rules as we are. They are operating on a different plane, but right next to us.’Karen Lloyd, ‘Episode 3: Existing Between’, Undead Matter (podcast), 17 September 2022, https://rwm.macba.cat/en/research/undead-matter-3-existing-between.

From this perspective, the desert becomes one of the most variegated environments on Earth, one that constantly tilts from paradise to hell (from a human perspective) and back again. A place of transformation, maybe like the spot in the display window at Stroom where Cyanobacteria time and again transformed into a non-living state. But did they die?

True, to us humans, they no longer seem to be in a productive cycle, but perhaps they have been transformed into other substances, allowing us to suspect that it is precisely in this unknown state of being that new possibilities may lurk. And so, I continue to take care of all Cyanobacteria, including when they are visually no longer there or are in a non-living state. Since our human perception and experience of time is limited, it cannot be up to us to determine the productivity of organisms, in whatever state they may be in. Here, the first law of thermodynamics, commonly known as the law of conservation of energy, becomes poetics, a reassuring mantra: energy and matter cannot be created or destroyed. . . . It is of such beauty and comfort to know that the amount of energy and matter remains the same. Everything is constantly becoming something else, a genuine definition of queerness.

Story #5: This Is Not a Pluralising Gesture | Nowish

[Photographers] may say, what has this to do with [photography], to which may be replied, everything!Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (London: University of Minnesota Press, 2018): ‘Geologists may say, what has this to do with geology, to which may be replied, everything!’ (p. 103). From the back cover: ‘Tracing the colour line of the Anthropocene, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None examines how the grammar of geology is foundational to establishing the extractive economies of subjective life and the earth under colonialism and slavery.’

Writing with light and capturing time are the foundation of the house of photography. But the house is not what it used to be. The roof leaks, the windows chink and the floor is creaky. There is a trail of ecological disaster dripping behind the manufacture of photographic equipment, the environment around (the once) Kodak and Agfa factories is polluted, the amount of photographic data we carelessly click away each day is guzzling more and more energy, and this is not to mention the problematic role that photography has played through its dominant socio-political power structures and harmful norms of defining, categorising, and setting the standard, creating the norm.

The question now is what to do with this house? Repair and renovate or tear it down and rebuild all over again? The latter is a sheer illusion, a way of thinking that fits into what Povinelli calls ‘settler late liberalism’Povinelli, Geontologies: ‘Settler late liberalism differentially debits and rewards persons based on their location within the divisions of empire’ (p. 25)., where the fairy tale of the self-made man is still being told and people think they are in control of their lives. Where toxicity can be cleaned up and heaven on earth is the ultimate pursuit. But let’s not doze off into white imaginaries here. Most toxicity is here to stay – it is in our bodies, in our soils, in our oceans. One of the big problems of toxicity is that it is not evenly distributed, not shared equally, or as Povinelli states very clearly about the politics of thinking about toxicity as systems of liberal complicity: ‘The people who created this embankment of purity around themselves have to be told that everybody has to drink their fair share of the shit.’Elizabeth A. Povinelli, ‘Remove! Replace! Restore!’, Canadian Art, 10 December 2018,My own exchange with photographic toxicity was mostly self-inflicted. Years of sniffing and touching chemicals in the photographic dark room gives me a nagging headache and itchy skin with every new contact. Facing this fact, I find comfort in Alexis Shotwell’s question: ‘Might it be better to understand complexity, and our own complicity in much of what we think of as bad, as fundamental to our lives?’Alexis Schotwell, Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times (London: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), back cover.

As a photographer, I hold myself co-accountable to photography’s contribution in determining the histories we perceive and the ones we fail to perceive. To add to the restoration process of the interstices of the house of photography, I concentrate on unlearning photography, a change in attitude to make photography more horizontal and less anthropocentric. Instead of pursuing a human understanding of reality shown through photographic representation, I try to envision the world without a camera, through a non-chemical production process and with a non-human gaze. When I look between my eyelashes through a crack in the wall of the house of photography, I picture a ‘living micro-organic photographic process’, in deep collaboration with Cyanobacteria and many other micro-organisms, an other-than-human, breathing assemblage, in which transformation is the image, and the result is always in progress.

Can you imagine listening beyond the edge of your own imagination?

Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening (Ignota Books, 2022), 24.

Listening to Cyanobacteria, I imagine a type of photography where, as a photographer, I am no longer in control of the actual image, but rather create the circumstances and conditions in which photographic images may evolve.

Editor's note. This contribution is part of the printed issue Trigger #5: Energy that was published in November 2023, in collaboration with FUTURES photography. More information here.